Abstract

Background

One of the rare complex congenital anomalies is truncus arteriosus—modified Van Praagh’s type 3A. Survival of this type of truncus arteriosus child beyond infancy without surgical treatment is unreported. Anesthesiologists do anesthetize children with complex congenital heart disease during the cardiac catheterization study. The final diagnosis of such children is often made after the anesthesia and cardiac catheterization study. We report a 12-year-old with truncus arteriosus with absent right pulmonary artery and main pulmonary artery with multiple Major Aorto-Pulmonary Collateral Arteries. (MAPCAs) for the right lung, who is surviving without surgical treatment.

Case presentation

A 12-year-old girl was brought by her parents to Meenakshi Hospital at Thanjavur (India) with complaints of shortness of breath during respiratory infection. The patient was diagnosed to have congenital heart disease at 6 years of age and not on any treatment. There was no history of cyanotic spell. Her echocardiography revealed tetralogy of Fallot, situs solitus, levocardia, large mal-aligned ventricular septal defect with bidirectional shunt, VSD size 12 mm, pulmonary atresia, moderate tricuspid regurgitation (TR pressure gradient, 103 mmHg), thickened aortic valve, grade II aortic regurgitation, right ventricular hypertrophy, intact interatrial septum, dilated right atrium/right ventricle, dilated coronary sinus, and persistent left superior vena cava, good biventricular function 65%, multiple MAPCAs, no coarctation of aorta, normal veno atrial, atrio-ventricular connections, normal pulmonary venous drainage, and no pericardial effusion. She underwent cardiac catheterization study for further evaluation under anesthesia. Her final diagnosis was truncus arteriosus with absent right pulmonary artery and main pulmonary artery with multiple MAPCAs for right lung, (truncus arteriosus—modified Van Praagh’s type 3A).

Conclusion

An anesthesiologist may be encountering such patients during cardiac catheterization study or emergency non-cardiac surgery, where an understanding of the complex anatomy (the aorta, left pulmonary artery, coronary artery, all arising from the common arterial trunk, the truncus arteriosus) and the physiology of their circulation would help in safe anesthesia. From our report, we conclude intra venous ketamine along with regional analgesia would be safe for sedating such patients coming for cardiac catheterization study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anesthesiologists do anesthetize children with complex congenital heart disease during the cardiac catheterization study. The final diagnosis of such children is often made after the anesthesia and cardiac catheterization study. We report a 12-year-old with truncus arteriosus with absent right pulmonary artery and main pulmonary artery with multiple Major Aorto-Pulmonary Collateral Arteries. (MAPCAs) for the right lung, who is surviving without surgical treatment. Good clinical history and assessment would help in their safe management.

Case presentation

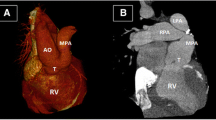

A 12-year-old girl was brought by the parents to Meenakshi Hospital at Thanjavur (India) with complaints of shortness of breath during respiratory infection. The patient was diagnosed to have congenital heart disease at 6 years of age and not on any treatment. There was no history of cyanotic spell. Her height was 130 cm and weight was 22 kg. She had mild mental retardation and pandigital clubbing. Her heart rate was 88/min, blood pressure 90/60 mmHg. SpO2 (saturation of oxygen by pulseoxymetry) was 78%. Under IV sedation with IV glycopyrrolate 0.1 mg, IV midazolam 0.4 mg, IV ketamine 10 mg bolus given thrice at 15-min interval, and local anesthesia infiltration with 1.5% lignocaine 4 ml, she underwent the procedure. There was right ventricular hypertrophy with large ventricular septal defect with absent right ventricular outflow tract. Aortic root angiogram revealed the truncus arteriosus, the common arterial trunk. There was no coronary anomaly. There was a left pulmonary artery arising from the posterolateral wall of the common arterial trunk distal to the common arterial trunk valve. The common arterial trunk continued as ascending aorta and right aortic arch with normal origin of major arteries and continued as descending aorta (Fig. 1). The main pulmonary artery and right pulmonary artery, ductus arteriosus, are absent. The right lung is supplied by 3 major MAPCAs (Major Aorto-Pulmonary Collateral Arteries)—one for each lobe. The MAPCA supplying the middle lobe had 75% ostial stenosis. She was finally diagnosed as having complex congenital heart disease—truncus arteriosus with absent right pulmonary artery and main pulmonary artery with multiple MAPCAs for the right lung. The patient was advised for surgical management at a higher center but parents deferred surgery. On follow up after 1.5 years, the child did not undergo any surgical intervention and remained the same symptomatically.

Cardiac catheterization study. a Antero-posterior view. b Lateral view. TA, truncus arteriosus, the common arterial trunk; Asc Ao, ascending aorta; LPA, left pulmonary artery; MAPCAs, major aorto-pulmonary collateral arteries; Co Ar, coronary artery; The aorta, left pulmonary artery, and coronary artery, all arising from the common arterial trunk, the truncus arteriosus

Discussion

The incidence of truncus arteriosus varies from 0.06 to 0.14 per 1000 live births (Reller et al., 2008; Hoffman & Kaplan, 2002). There are two principal classification systems for truncus arteriosus—The Collett and Edwards (Collett & Edwards, 1949) and Van Praagh and Van Praagh classification (Van Praagh & Van Praagh, 1965).

The nomenclature for truncus arteriosus is reviewed for the purpose of establishing a unified reporting system by Jacob et al. (Jacobs, 2000). The above-discussed patient comes under truncus arteriosus hierarchy level 3—truncus arteriosus with absence of one pulmonary artery (large aorta type with absence of one pulmonary artery). Retrospectively, the aortic valve with tricusps turned out to be common arterial trunk valve.

The truncus arteriosus babies are symptomatic in infancy, and the mortality is high if they are not operated. Rarely, they reach adolescence and adulthood without treatment. Patients reaching adolescence and adulthood without any treatment are reported in other types of truncus arteriosus (Mittal et al., 2006; Abid et al., 2015).

To our knowledge on reviewing the literature, a patient with this type of truncus arteriosus modified Van Praagh’s type 3A with absent one pulmonary artery reaching adolescence has not been reported in the literature. Our patient’s survival throws light on the natural history of this rare complex congenital heart disease. Embryologically, these lesions are secondary to conotruncal anomalies and left sixth arch anomaly. It is usually associated with DiGeorge syndrome, but genetic analysis of our patient has not been done.

Conclusions

An anesthesiologist may be encountering such patients during cardiac catheterization study or emergency non-cardiac surgery, where an understanding of the complex anatomy (the aorta, left pulmonary artery, coronary artery, all arising from the common arterial trunk, the truncus arteriosus) and the physiology of their circulation would help in safe anesthesia. Absent history of cyanotic spell in a cyanotic heart disease patient might give a clue to the diagnosis of non-dynamic obstruction or pulmonary atresia.

Safe anesthesia for such children coming for non-cardiac surgery/procedures has not been described. From our report, we conclude intra venous ketamine along with regional analgesia would be safe for sedating such patients coming for cardiac catheterization study.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s father for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- Asc Ao:

-

Ascending aorta

- Co Ar:

-

Coronary artery

- LPA:

-

Left pulmonary artery

- MAPCAs:

-

Major Aorto-Pulmonary Collateral Arteries.

- TA:

-

Truncus arteriosus, the common arterial trunk

- TR:

-

Tricuspid regurgitation

References

Abid D, Daoud E, Ben Kahla S, Mallek S, Abid L, Fourati H et al (2015) Unrepaired persistent truncus arteriosus in a 38-year-old women with an uneventful pregnancy. Cardiovasc J Afr 23;26(4):e6–e8

Collett RW, Edwards YE (1949) Persistent truncus arteriosus. A classification according to anatomic subtypes. Surg Chin North Am 29:1245

Hoffman JI, Kaplan S (2002) The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 39:1890

Jacobs ML (2000) Congenital heart surgery nomenclature and database project: truncus arteriosus. Ann Thorac Surg. 69(4 suppl):S50–S55

Mittal SK, Mangal Y, Kumar S, Yadav RR (2006) Truncus arteriosus type 1: a case report. Indian J Radiol Imaging 16:229–231

Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT, Correa A (2008) Prevalence of congenital heart defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998-2005. J Pediatr 153:807

Van Praagh R, Van Praagh S (1965) The anatomy of common aortico-pulmonary trunk (Truncus Arteriosus communis) and its embryonic implications. A study of 57 necropsy cases. Am J Cardiol 16:406–425

Acknowledgement

Dr. Omprakash Srinivasan MD DM (cardiac anesthesia) and Dr. Aparna Vijayaraghavan DNB (Paed), DM (pediatric cardiology) for their support.

Funding

Nil

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author’s individual contribution to the article is as follows: VV was involved in the clinical care of the patient, follow up of the patient, reviewing the literature, and the write-up. SM was involved in the clinical care of the patient, the diagnosis of the patient, and reviewing the literature and contributed to the write up. AG was involved in review of the literature and contributed to the write up and critical analysis of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s father for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vijayakumar, V., Muthuramalingam, S. & Ganesamoorthi, A. Truncus Arteriosus - modified Van Praagh’s Type 3A and Anesthesia: a case report.. Ain-Shams J Anesthesiol 12, 11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-020-00060-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42077-020-00060-3