Abstract

Background

Internal carotid artery high-grade stenosis is a major cause of stroke. Carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) is a reasonable approach for treatment of certain patients. Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) evaluated through breath holding index test can assess the outcome following CAS.

Aim

Evaluate changes in CVR before and after CAS.

Subjects and method

Thirty-two patients with 35 symptomatic internal carotid artery high-grade stenosis (> 70%) were enrolled by the mean of ultrasound screening. Breath holding index test was done using transcranial Doppler ultrasound before and after CAS.

Results

The study includes 32 patients (22 males and 10 females). The mean age was 61.91 ± 6.59 years. The main risk factor was hypertension (75.3%). All patients showed an increase in mean flow velocity and BHI following CAS (P < 0.001) on both ipsilateral and contralateral side. Both groups (70–90% and > 90% stenosis) showed similar improvement of CVR.

Conclusion

CAS improves CVR in all high grades of internal carotid artery stenosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internal carotid atherosclerosis is one of the main causes of ischemic stroke. About 25%–30% of all cerebral ischemic events are caused by large vessel atherosclerosis [1]. It was found that recurrence of stroke in patients with significant carotid stenosis was as high as 26% 2 weeks following the first event [2]. Strong relation was found between the degree of stenosis and infarct size as well [3].

Carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) has become a valid approach for the treatment of carotid stenosis [4]. Although long-term follow up of patients used to favor endarterectomy rather than carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) [5], still, this later procedure is indicated and remains cost-effective for high-risk patients [6] as well as patients younger than 70 years. In asymptomatic carotid stenosis, both methods showed, equally, low morbidity and mortality rate in short as well as long-term results [7].

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) is a regulating mechanism that is represented by the ability of cerebral arterioles to dilate or to constrict in order to maintain a constant cerebral blood flow in different conditions of local or systemic demand [4]. It was proven that changes in arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) level is a useful risk predictor for stroke in patients with severe carotid stenosis [8] and was suggested to be used in risk stratification for stroke in these patients [4].

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) monitoring is a well-documented method that has reliable results. It is relatively simple, non-invasive, repeatable, and less costly to evaluate cerebrovascular reactivity [1]. CVR can be evaluated by calculating the breath holding index (BHI), which is assessed by the changes in mean blood flow velocity (MFV) of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) following hypercapnia that is induced by a breath holding [9].

Aim

The aim of the study is to assess cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) before and after carotid artery angioplasty and stenting to evaluate its possible use as a predictor of outcome.

Subjects and methods

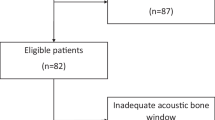

This is cross-sectional analytic study, enrolled 32 adult male and female Egyptian patients, presented to the stroke unit(s) of Kasr Al-Ainy (Cairo University) and Al-Demerdash (Ain Shams University) hospitals, both located in Cairo, Egypt, with cerebrovascular stroke or transient ischemic attacks. The enrolment period extended from December 2014 to February 2016, and the follow-up period extended to September 2016.

Inclusion criteria were based on the presence of significant (more than 70%) carotid artery stenosis ipsilateral to the symptomatic side of the brain. Exclusion criteria were less than 70% stenosis, intracranial pathologies other than stroke, and severe concurrent illness (renal, hepatic, heart failure, etc.).

Carotid stenosis was detected by screening all stroke patients with color-coded duplex ultrasound. Patients with > 70% symptomatic carotid stenosis were enrolled and then subdivided into two groups: 70–90% stenosis and > 90 stenosis. They, then, underwent transcranial Doppler (TCD) assessment of cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) by breath holding index (BHI). They were, then, sent for angioplasty and stenting (CAS). One week following the procedure, TCD for BHI was repeated to assess CVR.

Ultrasound examination

TCCD was done in the neurovascular lab of the Cairo University Neurosonology Unit (CUNU). Carotid stenosis was assessed according to NASCET and flow analysis [10] using Philips iU22 machine (22100 Bothel Evrett Highway, Bothel, WA. 98021 USA).

Breath holding index was assessed by Doppler “Multidop” T device (Compumedics GmbH, Josef-Schuttler str. 2 D-78224 Singen, Deutschland/Germany). It was performed using headset to fix the probe (2 MHz) during the test. Patients were instructed to breathe quietly for 3 min during which the mean flow velocity in the MCA proximal segment was measured. Then, the patient was asked to hold his breath for at least 24 s. The maximum increase in mean flow velocity following regaining of breathing was recorded for 3 s regardless of the time of onset of changes (as the time of onset varies between patients). BHI was calculated according to the following formula [11]:

Angiography and assessment of collateral circulation

Using the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology/Society of Interventional Radiology (ASITN/SIR) collateral scale, based on DSA, it classifies the cerebral collateral status to grades from 0 to 4. When there is a dichotomized score, “inadequate collaterals” (score of 0, 1, or 2) versus “adequate collaterals” (score of 3 or 4) was used [12].

Carotid angiography, angioplasty, and stenting

All patients underwent the same procedure:

-

1.

Eight French guiding catheter MAC 40 degree [Boston Scientific] in the access phase

-

2.

Transend soft tip 0.014 in. [Stryker] microwire to bypass the lesion

-

3.

Spider filter [ev3-Medtronic] as a distal protection device

-

4.

Carotid wall stent [Boston Scientific] closed-cell design

-

5.

All patients had post-dilatation balloon angioplasty with Sterling balloons [Boston Scientific], while only patients with severe stenosis more than 90% had pre-dilatation with Maverick balloons [Boston Scientific].

Written consent was obtained either from the patient or from a close relative. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University.

Statistical method

Data were coded and entered using the statistical package SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 23 (reference #: 4038592, modified date: 26 May 2016), IBM Inc. Chicago, IL, USA. Data were analyzed in March to May 2017, in Community Medicine and Biostatistics Department of Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Egypt. Data was summarized using mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum in quantitative data and using frequency (count) and relative frequency (percentage) for categorical data. Comparisons between quantitative variables were done using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests. For comparison of serial measurements (pre and post) within each patient, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used (Chan, 2003). P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

The study included 32 patients, 22 males and 10 females. Two of the males and one of the females had bilateral stenosis; therefore, a total of 35 patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis were included. The mean age was 61.91 ± 6.59 years. Risk factors are shown in Table 1.

The degree of stenosis and different pathologies are shown in Table 2

Mean flow velocity as well as breath holding index showed statistically significant improvement on the ipsilateral and contralateral side after carotid artery stenting (CAS) as shown in Table 3.

Both groups (70–90% stenosis and >90 stenosis) had similar cerebrovascular reactivity dysfunction and improved to the same extent, showing no statistically significant difference in BHI before or after CAS (P > 0.05). Patients with bilateral significant carotid stenosis (n = 5) showed better cerebrovascular reactivity compared to those with unilateral significant stenosis (n = 30) before CAS (P < 0.05), yet following CAS, there was no significant difference as patients with bilateral stenosis showed almost similar values in BHI before and after CAS (Table 4).

Discussion

Carotid atheromatosis is one of the main causes of ischemic stroke. In recent years, carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) has become a valid approach for the treatment of carotid stenosis. However, little is known on the change of hemodynamic after stenting. Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) has become widely recognized and valid indicator for testing the hemodynamic status of cerebral circulation, and TCD is today a well-documented method with reliable results being a relatively simple, non-invasive, repeatable, and less costly to evaluate CVR.

This study shows an improvement in cerebrovascular reactivity following CAS of severe symptomatic carotid artery stenosis. The improvement was similar in patients with 70–90% stenosis and with > 90% stenosis, indicating that both groups benefit to the same extent from revascularization.

Hemodynamic variability of the brain occurs in the face of changes in perfusion pressure as well as hypercapnia and/or hypoxia through autoregulation or cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR). This later phenomenon control, as well, the volume of blood reaching different brain regions according to its activity [13]. Breath holding index is a simple test that has been used early by Ratnatunga and Adiseshiah [14]. The test is done by breath-holding to prevent CO2 elimination, which results in a progressive increase in PaCO2 of blood which is accompanied by increased flow velocity in the examined vessel which in turn, under certain conditions, indicate an increase in flow volume.

It was once stated that there was a “variable” relation between hemodynamic changes and degree of carotid stenosis [15]. More recent studies showed that the degree of hemodynamic impairment (HDI) was directly related to the degree of stenosis, yet this HDI was not strongly associated with the presence of deep watershed (DWS) infarcts. These infarcts were rather related to plaque inflammation and presence of micro-embolic signals (MES) [16].

All patients’ cerebrovascular reactivity improved following revascularization. They showed a normalization (increase) of the BHI (P < 0.001) in the ipsilateral MCA following carotid angioplasty and stenting. No difference in BHI was found between patients with 70–90% stenosis and those with > 90% stenosis either before or after CAS. This concord with the fact that carotid endarterectomy was equally highly effective for all patients with stenosis 70–99% yet showing only some moderate benefit in patients with less than 70% stenosis [17].

Cerebrovascular reactivity improved, as well, on the contralateral side despite being within normal range before stenting. It can be explained by the active contribution of the contralateral carotid system in collateral supply through an increase in its flow volume [18]. This finding points to a hemodynamic stress on the contralateral side also that is corrected following revascularization.

Astonishingly, patients with bilateral carotid stenosis had a better cerebrovascular reactivity compared to patients with unilateral carotid stenosis prior to CAS. This could be explained by expansion of the potential collateral circulation in case of bilateral stenosis and due to the vasoconstriction of the arteriolar resistance regarding the hyperemia as a response to unilateral perfusion and to the unilateral rehabilitation of self-regulation mechanism [19]. This preference became no longer significant post-CAS with correction of the stenotic side. Source of collaterals, also, affects largely its efficacy; anterior and/or posterior communicating arteries’ collateral origin are surpassing ophthalmic and leptomeningeal ones [19, 20].

Limitations of the study were the small number of patients who were fit to perform the test and variation in the breath holding time (24 to 30 s) depending upon the patient capacity.

Conclusion

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) restores to normal following carotid angioplasty and stenting. The efficacy is equal in all high grades of carotid stenosis (70–99%). Contralateral CVR improves also, indicating a relative hemodynamic stress on that side as well. Patients with bilateral high-grade stenosis seem to have better reactivity compared to patients with unilateral stenosis.

References

Jackson BM, English SJ, Fairman RM, Karmacharya J, Carpenter JP, Woo EY. Carotid artery stenting: identification of risk factors for poor outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(1):74–9.

Tsantilas P, Kühnl A, Kallmayer M, Knappich C, Schmid S, Kuetchou A, et al. Stroke risk in the early period after carotid related symptoms: a systematic review. J Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;56(6):845–52.

Alagoz AN, Acar BA, Acar T, Karacan A, Demiryürek BE. Relationship between carotid stenosis and infarct volume in ischemic stroke patients. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:4954–9.

Gupta A, Chazen JL, Hartman M, Delgado D, Anumula N, Shao H, et al. Cerebrovascular reserve and stroke risk in patients with carotid stenosis or occlusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2012;43(11):2884–91.

Mas JL, Arquizan C, Calvet D, Viguier A, Albucher JF, Piquet P, et al. Long-term follow-up study of endarterectomy versus angioplasty in patients with symptomatic severe carotid stenosis trial. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2750–6.

Almekhlafi MA, Hill MD, Wiebe S, Goyal M, Yavin D, Wong JH, et al. When is carotid angioplasty and stenting the cost-effective alternative for revascularization of symptomatic carotid stenosis? A Canadian health system perspective. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35(2):327–32.

Mannheim D, Falah B, Karmeli R. Endarterectomy or stenting in severe asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Isr Med Assoc J. 2017;19(5):289–92.

Reinhard M, Schwarzer G, Briel M, Altamura C, Palazzo P, King A, et al. Cerebrovascular reactivity predicts stroke in high-grade carotid artery disease. Neurology. 2014;83(16):1424–31.

Stoll M, Seidel A, Treib J, Hamann GF. Influence of different techniques of breath holding on the measurement of cerebrovascular reserve in carotid artery disease. Stroke. 1996;27(6):1132–3.

von Reutern GM, Goertler MW, Bornstein NM, Del Sette M, Evans DH, Hetzel A, et al. Grading carotid stenosis using ultrasonic methods. Stroke. 2012;43(3):916–21.

Markus HS, Harrison MJ. Estimation of cerebrovascular reactivity using transcranial Doppler, including the use of breath-holding as the vasodilatory stimulus. Stroke. 1992;23(5):668–73.

Ben Hassen W, Malley C, Boulouis G, et al. Inter- and intraobserver reliability for angiographic leptomeningeal collateral flow assessment by the American Society of Interventional and Therapeutic Neuroradiology/Society of Interventional Radiology (ASITN/SIR) scale. J NeuroInterv Surg Published Online First: 21 August 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2018-014185.

Fierstra J, Sobczyk O, Battisti-Charbonney A, Mandell DM, Poublanc J, Crawley AP, et al. Measuring cerebrovascular reactivity: what stimulus to use? J Physiol. 2013;591(23):5809–21.

Ratnatunga C, Adiseshiah M. Increase in middle cerebral artery velocity on breath holding: a simplified test of cerebral perfusion reserve. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1990;4(5):519–23.

Powers WJ, Press GA, Grubb RL, Gado M, Raichle ME. The effect of hemodynamically significant carotid artery disease on the hemodynamic status of the cerebral circulation. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106(1):27–34.

Moustafa RR, Izquierdo-Garcia D, Jones PS, Graves MJ, Fryer TD, Gillard JH, et al. Watershed infarcts in transient ischemic attack/minor stroke with > or = 50% carotid stenosis: hemodynamic or embolic? Stroke. 2010;41(7):1410–6.

Orrapin S, Rerkasem K. Carotid endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD001081.

Fang H, Song B, Cheng B, Wong KS, Xu YM, Ho SS, et al. Compensatory patterns of collateral flow in stroke patients with unilateral and bilateral carotid stenosis. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:39.

Zachrisson H, Blomstrand C, Holm J, et al. Changes in middle cerebral artery blood fl ow after carotid endarterectomy as monitored by transcranial Doppler. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:285–90.

Reinhard M, Müller T, Guschlbauer B, Timmer J, Hetzel A. Dynamic cerebral autoregulation and collateral flow patterns in patients with severe carotid stenosis or occlusion. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003;29(8):1105–13.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

The data set is not publicly available due to institutional rules.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study design. SA and IIZ selected the cases and did the neurological and sonographic examination of patients. AAE and IIZ did the endovascular interventional part. Data were pulled by all the authors in one master sheet, and all of them contributed in the paper conception and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written consent was obtained from each patient after a thorough explanation of the procedure. The study was approved by the local ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, in March 16, 2015, and received final ethical approval from the ethical committee of the Cairo University in March 26, 2015.

All patients received the standard care for their condition. The study was observational, with no unapproved or experimental procedures used.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashem, S.ES., Belal, E.S., Hegazy, M.M. et al. Cerebrovascular reactivity recovery following carotid angioplasty and stenting. Egypt J Neurol Psychiatry Neurosurg 55, 32 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-019-0071-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41983-019-0071-1