Abstract

Background

[F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography is routinely used for assessing Takayasu arteritis patients. However, extra-vessel [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake has not been evaluated in detail in these patients. We aimed to describe the extent and distribution of extra-vascular [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake on positron emission tomography/computed tomography in Takayasu arteritis patients. Seventy-three [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans from 64 consecutive Takayasu arteritis patients (59 women, mean age, 35.4 years; range, 13 to 71 years) and 40 scans from age-matched controls (36 women, mean age, 37.8 years; range, 13 to 70 years) were examined. We graded [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in large vessels using a 4-point scale and evaluated extra-vessel findings. Factors correlated with disease activity were examined. We evaluated the relationship between disease activity according to the National Institutes of Health score with extra-vessel findings, as well as other inflammatory markers (e.g., white blood cell count and C-reactive protein level).

Results

Extra-vessel involvement was present in 50 of 73 (68.4%) scans, specifically at the following sites: lymph nodes, 1.4%; thyroid glands, 17.8%; thymus, 11.0%; spleen, 1.4%; vertebrae, 45.2%; and pelvic bones, 9.6%. Takayasu arteritis patients had higher [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the spine (P = 0.03) and thyroid glands (P = 0.003) than did controls; uptake in other regions was comparable between groups. Compared with inactive patients, those with active Takayasu arteritis had a higher number of [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake sites in the vasculature (P = 0.001). Finally, patients with a National Institutes of Health score of ≥ 1 had significantly higher extra-vascular involvement (P = 0.008).

Conclusions

Extra-vessel [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake may be present in the context of Takayasu arteritis-related inflammatory processes. Information on extra-vascular [F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake may be useful for detecting and evaluating inflammatory processes when interpreting positron emission tomography/computed tomography scans obtained from Takayasu arteritis patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Large vessel vasculitis, which includes Takayasu arteritis (TA) and giant cell arteritis, is a rare, chronic inflammatory disease that affects the walls of the aorta and its main branches, as well as the coronary and pulmonary arteries. The incidence of TA is estimated to be two in 1 million individuals; this disease has a high prevalence in Japan (Toshihiko 1996). The mean age of onset is 35 years, and women are disproportionately affected by this disease (2 to 25-fold higher). TA is potentially life-threatening, with a mortality rate as high as 35%. Although autoimmune processes driven by antigens have been speculated to cause TA, no specific antigen or stimulus has been identified, and its pathogenesis remains unknown (Kerr et al. 1994; Blockmans et al. 2009).

TA involves non-specific symptoms, such as fever and general weakness. Hence, diagnosis and evaluation of disease activity are difficult. Parameters such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are also non-specific and contribute little towards the estimation of disease activity (Hoffman and Ahmed 1998).

Considering that the management of TA involves long-term treatment with steroids, it is imperative to make an accurate diagnosis. Diagnoses are typically made using multiple modalities, including ultrasound (US), angiography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Angiography has been used to evaluate vessel stenosis, occlusion, and aneurysm formation. However, angiography-based diagnoses can be operator-dependent and subjective. Aortic wall thickening on contrast-enhanced CT is a typical finding in TA (Restrepo et al. 2011). On MRI, thickened walls can be observed, in addition to mural edema (Desai et al. 2005; Nastri et al. 2004).

[F-18]fluorodeoxyglucose ([F-18]FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) imaging can be used to detect inflammatory processes in the vascular wall; this technique can identify more lesions than MRI (Webb et al. 2004; Walter et al. 2005; Meller et al. 2003). When biopsy, US, and MRI findings are unremarkable, additional examination with [F-18]FDG PET/CT can reveal TA-related inflammation. Reports have shown that [F-18]FDG PET/CT is useful for the detection of active inflammation in patients with TA and can be used to assess the response to steroid treatment (Tezuka et al. 2012; Kobayashi et al. 2005). As TA is a pan-arteritis disorder, [F-18]FDG PET/CT could be appropriate for assessing whole-body inflammatory processes. Approximately 30% of patients with TA have other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as Hashimoto disease or inflammatory bowel disease (Kerr et al. 1994). In patients with giant cell arteritis, splenic [F-18]FDG uptake is elevated, and this can be treated using steroids (De Winter et al. 2000). The use of [F-18]FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis of TA has been increasing; therefore, it is essential to understand extra-vessel findings on [F-18]FDG PET/CT in patients with TA. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no studies regarding extra-vessel findings on [F-18]FDG PET/CT in TA patients. Hence, this study aimed to describe the extent and distribution of extra-vascular [F-18]FDG uptake on [F-18]FDG PET/CT in TA patients.

Methods

Ethics

This study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics review committee of Tokyo Medical and Dental University, and the requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Study population

This was a retrospective study. Sixty-four consecutive patients with a total of 73 [F-18]FDG PET/CT scans obtained at our university hospital from 2006 to 2016 (59 women, five men; mean age, 35.4 years; range, 13 to 71 years) were included in the study. A diagnosis of TA was made using the American College of Rheumatology criteria (Arend et al. 1990) and the Guideline for Management of Vasculitis Syndromes (Japanese Circulation Society 2011), as described in a previous study (Tezuka et al. 2012). Disease activity was defined based on the National Institutes of Health criteria (Kerr et al. 1994). Forty age-matched individuals without TA (36 women, four men; mean age, 37.8 years; range, 13 to 70 years) were recruited as the control group, and one [F-18]FDG PET/CT scan from each individual was examined.

Imaging protocol

Patients fasted for at least 4 h before the examination and were confirmed to have glucose level < 200 mg/dl before the administration of [F-18]FDG. A total of 3.7 MBq/kg of [F-18]FDG was administered intravenously 1 h before the scan. Whole-body images were acquired using Aquiduo (Toshiba Medical, Tokyo, Japan), consisting of a combination of a full-ring PET scanner with lutetium oxyorthosilicate crystals and a 16-row multiple-detector CT scanner. The CT parameters for attenuation correction were as follows: tube voltage of 120 kV, tube current of 150 mA, field of view of 500 mm, pitch of 15.0, and slice thickness of 2.0 mm. PET emission data were obtained in the 3D mode using the following parameters: 2 min in each bed position (for 16 to 18 min in total), matrix size of 256 × 256, and Gaussian filter size of 5 mm.

Image interpretation

Two board-certified nuclear medicine physicians examined the PET images. We graded [F-18]FDG uptake in large vessels using a four-point scale, as described in a previous study, with accumulation in the liver as a reference (Walter et al. 2005) (Slart 2018). The grades were as follows: 0, no uptake present; 1, low-grade uptake (uptake present, but lower than that in the liver); 2, intermediate-grade uptake (uptake similar to that in the liver); and 3, high-grade uptake (uptake higher than that in the liver). We defined extensive inflammation as involvement of the aorta and major aortic branches. We defined limited inflammation as either involvement of the aorta or involvement of major aortic branches.

We evaluated extra-vessel findings using uptake in the mediastinum blood pool as a reference, except for the spleen. [F-18]FDG accumulation higher than that in the mediastinum blood pool was considered significant. To diagnose splenic involvement, we considered splenic uptake greater than hepatic uptake to be positive. FDG uptake was classified into 2 patterns: focal and diffuse.

We evaluated the relationship between disease activity according to National Institutes of Health score with extra-vessel findings, as well as other inflammatory markers (e.g., white blood cell count (WBC) count, CRP, and ESR).

Statistics

Categorical variables are denoted as frequencies or percentages, while continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviation. Disease activity, extra-vessel findings, and other inflammatory markers were compared using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the independent-samples t test and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Study population

Clinical characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. Fifty-five of 73 scans showed indications of active disease (75.3%), while 19 showed the inactive form of the disease (24.7%). Forty-four of 73 scans (60.2%) were obtained from patients undergoing steroid treatment, and 29 (59.7%) were from patients not undergoing steroid treatment.

Whole-body [F-18]FDG PET/CT findings

Vascular involvement was present in 55 of 73 scans (75.3%). Among these, 18 (24.7%) showed Grade 1, 24 (32.9%) showed Grade 2, and 13 (17.8%) showed Grade 3 (Table 2). [F-18]FDG uptake in vessels was detected in a median of 2.1 (range, 0 to 8) monitored sites. Twenty-seven of 73 scans (37.5%) showed extensive inflammation, with involvement of the aorta and major aortic branches. In contrast, 28 of 73 (38.3%) scans revealed limited inflammation (either involvement of the aorta or involvement of major aortic branches).

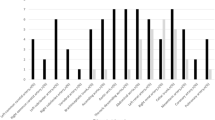

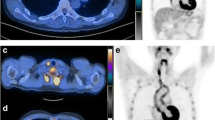

Extra-vessel involvement was present in 50 of 73 (68.4%) scans, specifically at the following sites: lymph nodes, 1/73 (1.4%); thyroid glands, 13/73 (17.8%); thymus, 8/73 (11.0%, Fig. 1); spleen, 1/73 (1.4%); and bone marrow, 33/73 (55.6%). Among patients who showed FDG uptake in thyroid glands, one patient who demonstrated diffuse FDG uptake in bilateral thyroid gland was diagnosed with papillary carcinoma (1/13, 7.7%), and 4 patients had abnormal thyroid function (3/13, 23.1%). Bone marrow involvement (Fig. 2) was present in 40 (54.8%) scans: vertebrae alone in 33 (45.2%) and both vertebrae and pelvic bones in 7 scans (9.6%). All findings are summarized in Table 3. No tumors or other diseases were identified in bone marrow during follow-up. In addition, [F-18]FDG uptake was present in the pharynx, breast tissue, ovary, and uterus; however, this was considered to be physiological uptake.

[F-18]FDG PET/CT scan of an 18-year-old woman diagnosed with Takayasu arteritis and an age-matched control patient. [F-18]FDG uptake is present in the right and left common carotid arteries and aortic arch (arrows). Note the [F-18]FDG uptake in vertebrae and pelvic bones (arrowheads), compared with the control

Vessel and extra-vessel involvement were present both individually and in combinations: combined vessel and extra-vessel involvement was detected in 41/73 (56.9%) scans, vessel involvement alone in 13/73 (18.1%) scans, and extra-vessel involvement alone in 8/73 (11.1%) scans. The remaining 10/73 (13.9%) scans showed no involvement.

Comparison with normal control

Patients with TA had higher [F-18]FDG uptake in the spine (P = 0.03) and thyroid glands (P = 0.003) than did the normal controls. [F-18]FDG uptake in pelvic bones (P = 0.425), thymus (P = 1), spleen (P = 0.5), and lymph nodes (P = 1) was comparable between groups (Table 4).

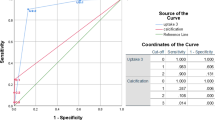

Disease activity

Patients with active TA had a higher number of [F-18]FDG uptake sites in the vasculature than did those with inactive TA (P = 0.001) (Table 5). The number of extra-vessel findings was not significantly correlated with disease activity (P = 0.542). Although the existence of extra-vessel involvement was not correlated with disease activity, patients with a National Institutes of Health score of ≥ 1 had increased extra-vascular involvement; this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.008). Among other inflammatory indicators, CRP level and ESR count were significantly correlated with disease activity (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.015). WBC count was not significantly correlated with disease activity (P = 0.424).

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is the first report on extra-vessel findings of Takayasu arteritis on [F-18]FDG PET/CT. We identified [F-18]FDG uptake in several extra-vascular regions and showed that TA patients had a greater number of extra-vessel findings than normal controls. We also demonstrated that extra-vessel findings were possibly correlated with disease activity, suggesting that extra-vessel [F-18]FDG uptake may be present in the context of active inflammation in TA patients.

Many patients in the present study showed [F-18]FDG accumulation in the bone marrow of vertebrae and pelvic bones. Elevated [F-18]FDG accumulation in bone marrow is related to bone marrow activation, as well as the elevation of WBC count and CRP level (Inoue et al. 2009). [F-18]FDG accumulation in the bone marrow could also be due to red marrow hyperplasia caused by bleeding anemia or hematopoietic stimulation treatment (Gordon et al. 1997). In the current study, most patients had slightly low hemoglobin count (Table 1), but the extent was not severe. Moreover, TA patients showed greater FDG accumulation in the bone marrow than age-matched controls, indicating that a low hemoglobin level is not the primary factor for FDG uptake in the bone marrow. The inflammatory process caused by TA may affect hyperactivation of the bone marrow in TA patients.

In addition to bone marrow, [F-18]FDG uptake in thyroid glands was observed in the current study. Several studies have reported incidental [F-18]FDG accumulation in the thyroid glands on PET/CT. The frequencies of [F-18]FDG uptake in the thyroid gland were 1.6% for focal uptake and 2.1% for diffuse uptake (Soelberg and Bonnema 2012). Focal uptake was also related to the presence of malignant tumors (Soelberg and Bonnema 2012; King et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2009). In the current study, 17.8% of patients showed [F-18]FDG uptake in the thyroid glands, which is higher than the previously reported frequency in normal individuals. One patient diagnosed with papillary carcinoma also showed FDG uptake in the contralateral thyroid gland. These findings indicated that some factors in TA patients caused increased [F-18]FDG uptake in the thyroid glands. There are few reports on the relationship between TA and thyroiditis. The HLA types A24 and B52 may constitute genetic factors contributing to the coexistence of TA and Hashimoto thyroiditis (Horai et al. 2011).

Eight of 73 scans showed [F-18]FDG accumulation in the thymus. [F-18]FDG uptake in the thymus on PET/CT can be observed in normal patients; thus, increased [F-18]FDG uptake in the thymus can be difficult to interpret (Brink et al. 2001), and morphologic features are useful for differentiating physiological and hyperplastic uptake from malignant uptake. In this study, plain CT did not reveal any lesions in the thymus, suggesting that the uptake might have been physiological or hyperplastic. To the best of our knowledge, a relationship between TA and thymic lesions has not yet been reported.

One patient showed [F-18]FDG uptake in the spleen. Diffuse FDG uptake in the spleen can be observed in inflammatory conditions including infection, bacteremia, and sepsis (Love et al. 2005). Presumably, increased glucose usage by this organ is related to increased splenic activity in the context of infection. Moreover, inflammation caused by TA, or severe anemia (6.9 mg/dl) in the patient, could have caused diffuse FDG uptake in the spleen (Kim et al. 2014).

Only one patient showed [F-18]FDG uptake in the lymph nodes; thus, it is difficult to determine whether TA itself causes such accumulation. In one study, lymph node swelling and hepatomegaly in lymph nodes were present in the pre-pulseless stage of TA (Yotsuyanagi et al. 1995). Lymph node swelling and hepatomegaly are typically related to viral infection, rather than vasculitis, and there is no valid rationale for suspecting that TA causes such symptoms. We believe that [F-18]FDG uptake in the lymph nodes is uncommon in TA patients.

Extra-vessel [F-18]FDG uptake was present in patients with active and non-active forms of TA. The extent of extra-vessel [F-18]FDG uptake was not significantly different between groups. Patients with a National Institutes of Health score of ≥ 1 had a higher number of extra-vessel findings than did patients with a score of zero. Vascular uptake and overall uptake were related to disease activity. Extra-vessel [F-18]FDG accumulation could thus be correlated with disease activity. In some cases, extra-vessel [F-18]FDG uptake reduced or completely resolved after treatment; however, some of these did not respond to treatment. It was previously reported that coexistent inflammatory bowel disease was independent of TA but that erythema nodosum could be resolved after treatment for TA (Kerr et al. 1994). Therefore, extra-vascular findings that do not respond to treatment can still be related to TA. TA patients had greater extra-vessel [F-18]FDG accumulation than normal controls, suggesting that extra-vascular [F-18]FDG accumulation is related to TA-related inflammatory processes. Considering that serological parameters such as ESR and CRP are not specific inflammatory markers of TA activity, extra-vessel findings may be a potential indicator of inflammation in TA.

This study had some limitations. First, the study design was retrospective. Second, many patients were under steroid and immunosuppressive therapy; therefore, disease onset and the highly active phase of TA could not be evaluated. Thirdly, we utilized 4 h of fasting time for all patients. Relatively short fasting time may lead to inadequate suppression of FDG uptake in the mediastinum blood pool and liver. Longer fasting time may render a more precise evaluation of FDG uptake with suppressed and stable FDG uptake in the reference organs. Further research is necessary to understand the relationship between disease activity and extra-vessel [F-18]FDG uptake in TA patients; the clinical applicability of extra-vessel findings should also be evaluated.

Conclusions

In this study, we characterized extra-vascular [F-18]FDG uptake on [F-18]FDG PET/CT in TA patients. Our results indicated that extra-vessel [F-18]FDG uptake may be present in the context of TA-related inflammatory processes. Information regarding extra-vascular [F-18]FDG uptake may be useful for detection and evaluation of inflammatory processes when interpreting PET/CT scans obtained from TA patients. These findings may increase our understanding of the mechanism of inflammation in TA and the cause of symptoms in affected patients.

Availability of data and materials

The data are not available for public access because of patient privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- PET/CT:

-

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- TA:

-

Takayasu arteritis

- WBC:

-

White blood cell count

References

Arend WP, Michel BA, Bloch DA, Hunder GG, Calabrese LH, Edworthy SM et al (1990) The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 33:1129–1134

Blockmans D, Bley T, Schmidt W (2009) Imaging for large-vessel vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 21:19–28

Brink I, Reinhardt MJ, Hoegerle S, Altehoefer C, Moser E, Nitzsche EU (2001) Increased metabolic activity in the thymus gland studied with 18F-FDG PET: age dependency and frequency after chemotherapy. J Nucl Med 42:591–595

Chen W, Parsons M, Torigian DA, Zhuang H, Alavi A (2009) Evaluation of thyroid FDG uptake incidentally identified on FDG-PET/CT imaging. Nucl Med Comm 30:240–244

De Winter F, Petrovic M, Van de Wiele C, Vogelaers D, Afschrift M, Dierckx RA (2000) Imaging of giant cell arteritis: evidence of splenic involvement using FDG positron emission tomography. Clin Nucl Med 25:633–634

Desai MY, Stone JH, Foo TK, Hellmann DB, Lima JA, Bluemke DA (2005) Delayed contrast-enhanced MRI of the aortic wall in Takayasu’s arteritis: initial experience. AJR Am J Roentgenol 184:1427–1431

Gordon BA, Flanagan FL, Dehdashti F (1997) Whole-body positron emission tomography: normal variations, pitfalls, and technical considerations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:1675–1680

Hoffman GS, Ahmed AE (1998) Surrogate markers of disease activity in patients with Takayasu arteritis. A preliminary report from The International Network for the Study of the Systemic Vasculitides (INSSYS). Int J Cardiol 66(Suppl 1):S191–S194 discussion S195

Horai Y, Miyamura T, Shimada K, Takahama S, Minami R, Yamamoto M et al (2011) A case of Takayasu’s arteritis associated with human leukocyte antigen A24 and B52 following resolution of ulcerative colitis and subacute thyroiditis. Intern Med 50:151–154

Inoue K, Goto R, Okada K, Kinomura S, Fukuda H (2009) A bone marrow F-18 FDG uptake exceeding the liver uptake may indicate bone marrow hyperactivity. Ann Nucl Med 23:643–649

Japanese Circulation Society (2011) Guideline for management of vasculitis syndrome (JCS 2008). Circulation. 75:474–503

Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, Leavitt RY, Fauci AS, Rottem M et al (1994) Takayasu arteritis. Ann Int Med 120:919–929

Kim K, Kim SJ, Kim IJ, Kim DU, Kim H, Kim S et al (2014) Factors associated with diffusely increased splenic F-18 FDG uptake in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Nucl Med Mol Imaging 48:137–143

King DL, Stack BC Jr, Spring PM, Walker R, Bodenner DL (2007) Incidence of thyroid carcinoma in fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-positive thyroid incidentalomas. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137:400–404

Kobayashi Y, Ishii K, Oda K, Nariai T, Tanaka Y, Ishiwata K et al (2005) Aortic wall inflammation due to Takayasu arteritis imaged with 18F-FDG PET coregistered with enhanced CT. J Nucl Med 46:917–922

Love C, Tomas MB, Tronco GG, Palestro CJ (2005) FDG PET of infection and inflammation. Radiographics. 25:1357–1368

Meller J, Strutz F, Siefker U, Scheel A, Sahlmann CO, Lehmann K et al (2003) Early diagnosis and follow-up of aortitis with [(18) F]FDG PET and MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:730–736

Nastri MV, Baptista LP, Baroni RH, Blasbalg R, de Ávila LF, Leite CC et al (2004) Gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional MR angiography of Takayasu arteritis. Radiographics. 24:773–786

Restrepo CS, Ocazionez D, Suri R, Vargas D (2011) Aortitis: imaging spectrum of the infectious and inflammatory conditions of the aorta. Radiographics. 31:435–451

Slart R (2018) FDG-PET/CT(A) imaging in large vessel vasculitis and polymyalgia rheumatica: joint procedural recommendation of the EANM, SNMMI, and the PET Interest Group (PIG), and endorsed by the ASNC. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 45:1250–1269

Soelberg KK, Bonnema SJ, Brix TH, Hegedüs L (2012) Risk of malignancy in thyroid incidentalomas detected by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: a systematic review. Thyroid. 22:918–925

Tezuka D, Haraguchi G, Ishihara T, Ohigashi H, Inagaki H, Suzuki JI et al (2012) Role of FDG PET-CT in Takayasu arteritis: sensitive detection of recurrences. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 5:422–429

Toshihiko N (1996) Current status of large and small vessel vasculitis in Japan. Int J Cardiol 54 Suppl:S91–S98

Walter MA, Melzer RA, Schindler C, Müller-Brand J, Tyndall A, Nitzsche EU (2005) The value of [18F]FDG-PET in the diagnosis of large-vessel vasculitis and the assessment of activity and extent of disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 32:674–681

Webb M, Chambers A, Adil AN, Mason JC, Maudlin L, Rahman L et al (2004) The role of 18F-FDG PET in characterising disease activity in Takayasu arteritis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 31:627–634

Yotsuyanagi H, Chikatsu N, Kaneko Y, Kurokawa K (1995) Takayasu’s arteritis in prepulseless stage manifesting lymph node swelling and hepatosplenomegaly. Intern Med 34:455–459

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT designed the study and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. DT contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. All other authors contributed to data collection and interpretation and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review board of Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Approval number, M2017–351), and the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. The requirement for written informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuchiya, J., Tezuka, D., Maejima, Y. et al. Takayasu arteritis: clinical importance of extra-vessel uptake on FDG PET/CT. European J Hybrid Imaging 3, 12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41824-019-0059-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41824-019-0059-1