Abstract

Background

The present study aimed to analyze the association among depression, sleep quality, and quality of life using the Japanese version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP), and to compare these findings with those obtained using self-reported scales, in an urban male working population in Japan.

Methods

The present study included 324 middle-aged participants (43.8 ± 8.37 years) (participation rate: 69.5%). The Japanese version of the SCID-I/NP was administered by a single physician. Self-reported scales, including the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Assessment (PSQI), and 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) were used to assess depression, sleepiness, sleep quality, and quality of life, respectively. Participants were then divided into a major depressive disorder (MDD) and control group based on the results of structured interviews, following which self-reported scale scores were compared between the two groups.

Results

A total of 24 participants met criteria for MDD based on responses during structured interviews (current: 4; past: 20). Patients with MDD did not report feeling sleepier than those without psychiatric disorders (controls) (ESS: P = 0.184), although they experienced slightly poorer sleep quality (PSQI: P = 0.052). In addition, participants of the MDD group exhibited lower SF-36 subscale scores for general health (P = 0.002), vitality (P < 0.001), social functioning (P < 0.001), role emotional (P = 0.004), and mental health (P < 0.001) domains, and higher SDS scores (P = 0.038) compared to controls. The area under the receiver (AUC) operating characteristic curve for the detection of MDD was 0.631 and 0.706 for the SDS and mental health subscales, respectively.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that patients with MDD exhibit slightly poorer sleep quality and significantly poorer quality of life compared to controls, and that the SF-36 may be used as an alternative to the SDS to screen for depression in an urban male working population in Japan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Psychiatric disorders are highly prevalent and contribute substantially to the total burden on the general population (Murray et al. 2010). In particular, the Global Burden of disease report cites depressive disorders as a leading cause of burden (Ferrari et al. 2013), with more than 30,000 suicides committed in Japan alone between 1998 and 2011 (Ministry of Health et al. 2016). In 2005, the total cost due to depression among adults in Japan was estimated to be 2 trillion yen (164 trillion USD) (Sado et al. 2011). Thus, adequate diagnosis remains a priority for mental health researchers and professionals.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) (First et al. 2002) is a semi-structured instrument that allows for evaluation of the most common mental health problems and has been used as a reference in epidemiological studies (Kessler et al. 2004; Pez et al. 2010). In Japan, the SCID-I has been used to diagnose depression in pregnant patients (Yoshida et al. 2001) and patients with cancer (Akechi et al. 2004), and to verify psychiatric diagnoses in case-control studies (Tsuchiya et al. 2005). However, the SCID-I Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) (First et al. 2002) requires a trained physician and is time-consuming to administer, which may not be suitable for screening in large populations. Thus, few Japanese studies have utilized structured interviews in non-clinical settings, instead relying on self-reported questionnaires for the assessment of psychiatric/affective disorders. However, no studies to date have compared self-reported scores and SCID-I/NP results in a non-clinical Japanese population.

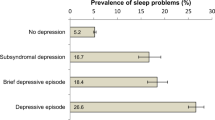

Suicidal ideation represents a severe symptom of depression that disproportionately affects Japanese men: Since 1998, 70.6 ± 0.01% of suicide victims in Japan have been male (Ministry of Health et al. 2016). Suicide attempts are not only a severe health problem, but also contribute substantially to the economic burden (Kadotani et al. 2014). Previous studies have further indicated that the severity of depression is associated with symptoms such as insomnia, daytime sleepiness, short sleep duration, and a reduction in productivity at work, even among undiagnosed individuals (Jha et al. 2016; Penninx et al. 2008; Plante et al. 2016; Baglioni et al. 2011; Nakada et al. 2015). Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to analyze the association among depression, sleep quality, and quality of life using the Japanese version of the SCID-I/NP (First et al. 2002), and to compare these findings with those obtained using self-reported scales, in an urban male working population in Japan in order to determine the most effective instrument for screening for depression.

Methods

Participants

The present study included participants enrolled in an ongoing sleep and health epidemiological study (Nakayama-Ashida et al. 2008; Kadotani et al. 2011). A cross-sectional survey was conducted in a group of 476 male employees at a wholesale company in Osaka, Japan, from January 26, 2004, to December 19, 2005. Ten participants were excluded because they changed their workplace during the survey. Thus, 466 male employees were invited to participate in our survey, and 396 answered the baseline questionnaire (85.0%). Of the total number of respondents, 324 underwent face-to-face SCID-I/NP interviews (participants), while 72 answered the baseline questionnaire but did not participate in the interview (non-participants). Sleep-wake cycle schedules were obtained using 7-day sleep logs with coincident wrist actigraphy (Actiwatch AW-Light: Mini-Mitter, Bend, Ore.), which was recorded using one-minute bins and analyzed by Actiware-Sleep ver. 3.4 (Mini-Mitter Co. Inc., Bend, Ore.). The weekday sleep debt was calculated as the difference in sleep duration between weekdays and weekends as estimated via actigraphy.

Structured interviews

All interviews were performed by a single physician, while another physician reviewed the results item by item. The clinical editions of the SCID-I and SCID-I/NP contain the same items, with the exception of those related to psychosis (First et al. 2002). Simple, brief items are used to screen for psychosis in the SCID-I/NP (First et al. 2002). Questions related to current or past depression were asked separately. Participants whose answers were positive for at least one of the two screening questions for depression were asked further questions about their specific depressive symptoms. Participants with more than five out of nine symptoms or those currently receiving treatment with antidepressants were classified into a current major depressive disorder (MDD) group, while those with past MDD diagnoses or who had been previously treated with antidepressants were classified into a past MDD group.

Questionnaires

The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) contains 20 items (Zung et al. 1965). Scores of ≤39, 40–49, and ≥50 on the Japanese SDS indicate no, mild, and moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms, respectively (Fukuda and Kobayashi 1983).

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) has been widely utilized to assess health-related quality of life (QOL) (McHorney et al. 1993). The SF-36 contains 36 items across eight subscales: physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical health (role-physical: RP), bodily pain (BP), general health perceptions (general health: GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), role limitations due to emotional problems (role emotional: RE), and mental health (MH). For each subscale, a score ranging from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) is calculated and standardized to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) (Johns 1991) and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Buysse et al. 1989) were used to assess sleepiness and sleep quality, respectively. Participants with ESS scores of >10 and those with PSQI global scores of >5 were classified as having sleepiness and sleep problems, respectively.

We used Japanese translations of the SCID-I/NP (First et al. 2002), SDS (Fukuda and Kobayashi 1983), ESS (Takegami et al. 2009), and PSQI (Doi et al. 2000), and the Japanese version 2 of the SF-36 (Fukuhara et al. 1998).

Statistical analysis

Categorical data are presented as proportions, while continuous data are presented as means and standard deviations. T-tests were used to compare differences in continuous data between participants and non-participants. Group proportions were compared using the chi-square test. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was performed to compare the screening performance of the questionnaires. Pairwise comparisons of ROC curves were performed by calculating the standard error of the area under the curve (AUC) and difference between the two AUCs. Statistical analyses were performed using MedCalc version 16.8.4 (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 85.0% (396/466) and 69.5% (324/466) of all male employees at the company responded to the baseline questionnaire and the SCID-I/NP, respectively (Fig. 1). No statistical differences between the participants and non-participants were observed with respect to age, body mass index, ESS, total sleep time (TST), or SF-36 subscale scores (Table 1).

Flow chart. Participants with both MDD and other psychiatric disorders were classified into the MDD group. All participants with current MDD had been receiving treatment at the time of the study. MDD, major depressive disorders; SCID-I/NP, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders Non-Patient Edition

Four participants had current MDD, all of whom had been receiving treatment at the time of the study. Twenty participants had received past diagnoses of MDD (Table 2). Six participants answered positively to the screening question related to dysthymic disorder, although they were diagnosed with different affective disorders: Of the four participants with past depression, one answered positively to the screening questions for MDD but did not meet the diagnostic criteria for MDD, and one was diagnosed with bipolar I disorder. None of the participants were diagnosed with psychotic or eating disorders. Thirteen participants were diagnosed with anxiety disorders (panic disorder, 1; generalized anxiety disorder, 2; specific phobia, 7; social phobia, 2; obsessive–compulsive disorder, 1), three of whom had received past diagnoses of MDD. Participants with current or past MDD were combined into the MDD group (n = 24), while those without psychiatric disorders were classified into the control group (n = 290) (Fig. 1).

Participants of the MDD group exhibited a slight impairment in sleep quality (Table 3). PSQI scores and rates of poor sleep quality (PSQI > 5) were higher in the MDD group, relative to those of controls. Sleepiness (ESS) and sleep time parameters (TST, weekday sleep debt, and SL) did not significantly differ between the MDD and control groups.

Depressive symptoms and mental health-related QOL were significantly impaired in the MDD group (Table 3). Overall SDS scores and SDS depression category scores were significantly worse in the MDD group. The GH, VT, SF, RE, and MH subscale scores of the SF-36 were significantly lower in the MDD group (Table 3).

ROC analyses revealed that the MDD group exhibited significantly poorer scores than controls on the SDS and five subscales of the SF-36 (Fig. 2) (Additional file 1: Table S1). The AUC was highest for the MH subscale. The diagnostic ability for depression was fair for the MH [AUC: 0.712 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.658–0.761), P = 0.0001] and poor for the SDS [AUC: 0.631 (95% CI: 0.574–0.686), P = 0.0319] scales. No significant difference in AUC values was observed between SDS and SF-36 subscale scores (SDS vs. GH: P = 0.3465, SDS vs. VT: P = 0.3103, SDS vs. SF: P = 0.8470, SDS vs. RE: P = 0.3036, SDS vs. MH: P = 0.0975).

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for the detection of MDD. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) is presented with 95% confidence intervals and p-values (Area = 0.5). SDS, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale; Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Health Survey (SF-36) subscales: GH, general health perceptions (general health); VT, vitality; SF, social functioning; RE, role limitations due to emotional problems (role emotional); and MH, mental health

Discussion

In the present study, we conducted SCID-I/NP interviews in an urban male working population in Japan (n = 324). Participants with MDD exhibited impaired sleep quality and mental health-related QOL, although no significant differences in sleepiness or sleep duration parameters were observed between the MDD and control groups. In our ROC analysis, the MH score had the highest AUC among the GH, VT, SF, RE, MH, and SDS scores, suggesting that MH may be a good alternative to the SDS to screen for depression in a Japanese working male population.

Previous studies have reported a strong association among sleep problems, insomnia, and depression (Ferrari et al. 2013). In accordance with these findings, we observed impaired sleep quality in participants with MDD. Surprisingly, however, we observed no association among depression, sleepiness, and sleep duration parameters (TST, SL, weekday sleep debt) (Table 3). Although this finding may have been due to our small sample size, is it also possible that treatment parameters influenced our results, as all participants with MDD were receiving treatment at the time of the study.

In our ROC analysis, GH, VT, SF, RE, MH of SF-36 exhibited slightly higher AUC and lower p-values than SDS. Previous studies have reported that negatively worded items in the SDS do not adequately screen for depression in the Japanese population (Umegaki et al. 2016). However, the SF-36 also contains negatively worded items, suggesting that factors other than negative wording are responsible for this difference. The SF-36 utilizes norm-based scoring, in which the scale and component summary scores have a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10 in the general population (McHorney et al. 1993). This norm-based scoring system may be beneficial for detecting changes in non-clinical settings, in which most participants are likely to score near the norm. Furthermore, we observed no significant differences in AUCs between scores on the SDS and these SF-36 subscales. Thus, these findings indicate that the SF-36 can be used as an alternative to the SDS to screen for depression.

The company setting of the present study may represent an ideal site for data collection, providing a sufficient number of full-time, non-shift-working male employees working in the same industry and with the same employer, which allowed us to control for work environment factors such as occupational participation, employment sector, and employment policies (Kadotani et al. 2011).

Only a few psychiatric epidemiological studies have been conducted in the general Japanese population. Although some non-clinical studies have used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kawakami et al. 2005), to our knowledge, previous Japanese studies utilizing the SCID-I were performed in clinical settings only. We used the SCID-I/NP in a Japanese working population. Among the 324 total participants, four (1.2%) and 20 (6.2%) had current and past diagnoses of MDD, respectively, while 13 (4.0%) had anxiety disorders. Furthermore, we observed no evidence of psychotic or eating disorders among participants of the present study, and that all patients with current MDD were undergoing treatment at the time of the study. As reported previously, the prevalence of affective and anxiety disorders is lower in Japan than in Western countries (Demyttenaere et al. 2004).

The present study possesses some limitations of note. Our target population was not representative of the Japanese population in general, but was specific to the working male population in a Japanese urban area. Furthermore, individuals with severe MDD or psychotic disorders could not attend work and thus could not participate in this study, which may have resulted in a lower prevalence of both disorders. Nevertheless, we had a high participation rate of 69.5% (324/466). This survey was a part of a sleep and health epidemiological study; thus, participants with better sleep quality (lower PSQI scores) may have been reluctant to participate. However, TST was similar in participants and non-participants (Table 1). Thus, our study sample did not appear to have a self-selection bias, and our estimate of prevalence may well represent that of the entire participant population (i.e., all male employees of this company in the Osaka prefecture) (Kadotani et al. 2011).

Conclusions

In the present study, participants with MDD exhibited slightly poorer sleep quality and significantly poorer QOL than those without. Our findings further indicate that the SF-36, especially the MH subscale, may be used as an alternative to the SDS for the screening of depression in the working Japanese male population.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the receiver

- BP:

-

Bodily pain

- ESS:

-

Epworth sleepiness scale

- GH:

-

General health perceptions (general health)

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- MH:

-

Mental health

- PF:

-

Physical functioning

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh sleep quality assessment

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- RE:

-

Role limitations due to emotional problems (role emotional)

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- RP:

-

Role limitations due to physical health (role-physical)

- SCID-I/NP:

-

Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders/non-patient edition

- SDS:

-

Zung self-rating depression scale

- SF:

-

Social functioning

- SF-36:

-

Medical outcomes study 36-item short form health survey

- SL:

-

Sleep latency

- TST:

-

Total sleep time

- VT:

-

Vitality

References

Akechi T, Okuyama T, Sugawara Y, Nakano T, Shima Y, Uchitomi Y. Major depression, adjustment disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder in terminally ill cancer patients: associated and predictive factors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(10):1957–65.

Baglioni C, Battagliese G, Feige B, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Voderholzer U, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:10–9.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds 3rd CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburg sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213.

Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90.

Doi Y, Minowa M, Uchiyama M, Okawa M, Kim K, Shibui K, et al. Psychometric assessment of subjective sleep quality using the Japanese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI-J) in psychiatric disordered and control subjects. Psychiatry Res. 2000;97:165–72.

Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJ, et al. Burden of depressive disorders by country, sex, age, and year: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001547.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, non-patient edition. (SCID-I/NP). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. (Japanese translation by S Takahashi, T Kitamura and S Okano).

Fukuda K, Kobayashi S. Manual of self-rating depression scale. Sankyo-bo: Tokyo; 1983.

Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, Hsiao A, Kurokawa K. Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36 Health Survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1037–44.

Jha MK, Minhajuddin A, Greer TL, Carmody T, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH. Early improvement in work productivity predicts future clinical course in depressed outpatients: findings from the CO-MED trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:1196–204.

Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–5.

Kadotani H, Nakayama AY, Nagai Y. Durability, safety, ease of use and reliability of a type-3 portable monitor and a sheet-style type-4 portable monitor. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2011;9:86–94.

Kadotani H, Nagai Y, Sozu T. Railway suicide attempts are associated with amount of sunlight in recent days. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–4:162–8.

Kawakami N, Takeshima T, Ono Y, Uda H, Hata Y, Nakane Y, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and treatment of common mental disorders in communities in Japan: preliminary finding from the World Mental Health Japan Survey 2002–2003. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:441–52.

Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):122–39.

McHorney CA, Ware Jr JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63.

Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan. Counter-suicide White Paper in 2016. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/wp/hakusyo/jisatsu/16/. Accessed 10 Oct 2016. (In Japanese).

Murray CJ, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet. 2010;380:2197–223.

Nakada Y, Murakami J, Kadotani H, Matsuo M, Itou H, Yamada N. A cross-sectional study on working hours, sleep duration and depressive symptoms in Japanese shift workers. J Oral Sleep Med. 2015;1:133–9.

Nakayama-Ashida Y, Takegami M, Chin K, Sumi K, Nakamura T, Takahashi K, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in the usual lifestyle setting as detected with home monitoring in a population of working men in Japan. Sleep. 2008;31:419–25.

Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Nolen WA, Spinhoven P, et al. The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17:121–40.

Pez O, Gilbert F, Bitfoi A, Carta MG, Jordanova V, Garcia-Mahia C, et al. Validity across translations of short survey psychiatric diagnostic instruments: CIDI-SF and CIS-R versus SCID-I/NP in four European countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(12):1149–59. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0158-6.

Plante DT, Finn LA, Hagen EW, Mignot E, Peppard PE. Subjective and objective measures of hypersomnolence demonstrate divergent associations with depression among participants in the Wisconsin sleep cohort study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12:571–8.

Sado M, Yamauchi K, Kawakami N, Ono Y, Furukawa TA, Tsuchiya M, et al. Cost of depression among adults in Japan in 2005. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65:442–50.

Takegami M, Suzukamo Y, Wakita T, Noguchi H, Chin K, Kadotani H, et al. Development of a Japanese version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (JESS) based on item response theory. Sleep Med. 2009;10:556–65.

Tsuchiya KJ, Takagai S, Kawai M, Matsumoto H, Nakamura K, Minabe Y, et al. Advanced paternal age associated with an elevated risk for schizophrenia in offspring in a Japanese population. Schizophr Res. 2005;76(2–3):337–42.

Umegaki Y, Todo N. Psychometric Properties of the Japanese CES-D, SDS, and PHQ-9 Depression Scales in University Students. Psychol Assess. 2016. doi.org/10.1037/pas0000351.

Yoshida K, Yamashita H, Ueda M, Tashiro N. Postnatal depression in Japanese mothers and the reconsideration of ‘Satogaeri bunben’. Pediatr Int. 2001;43(2):189–93.

Zung WW, Richards CB, Short MJ. Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic: further validation of the SDS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;13:508–15.

Acknowledgments

We express gratitude to the participants, their families, and the company for which they worked. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing. We would like to thank Y. Nakayama-Ashida, M. Takegami, K. Chin, K. Sumi, T. Nakamura, K. Takahashi, T. Wakamura, S. Horita, Y. Oka, I. Minami, and S. Fukuhara for data collection.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology; a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI)(23591672, 26507006); Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan (H22-Nanchi-Ippan-008); and research grants from PRESTO JST, the Suzuken Memorial Foundation, the Takeda Science Foundation, the Mitsui Life Social Welfare Foundation, the Chiyoda Kenko Kaihatsu Jigyodan Foundation, the Health Science Center Foundation; and an Intramural Research Grant (23–3, 26–2) for Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders from NCNP.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

HK conceived of and designed the study, and drafted the manuscript. TK and HK were responsible for data collection. HK conducted the statistical analyses and interpreted the data. HI assisted in the drafting of the manuscript. HA, MT, MM, and NY commented on drafts of the manuscript and assisted with interpretation of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was approved by the Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine Ethics Committee (E-37) and the ethics committee of the Shiga University of Medical Science (25–175). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to participation.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Diagnosis evaluations. (DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kadotani, T., Kadotani, H., Arai, H. et al. Comparison of self-reported scales and structured interviews for the assessment of depression in an urban male working population in Japan: a cross-sectional survey. Sleep Science Practice 1, 9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-017-0010-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41606-017-0010-y