Abstract

A feeding trial was designed to assess the effects of dietary protein and lipid content on growth, feed utilization efficiency, and muscle proximate composition of juvenile mandarin fish, Siniperca scherzeri. Six experimental diets were formulated with a combination of three protein (35, 45, and 55%) and two dietary lipid levels (7 and 14%). Each diet was fed to triplicate groups of fish (8.3 ± 0.1 g) to apparent satiation for 8 weeks. The results showed that growth performance in terms of weight gain (WG) and specific growth rate (SGR) increased with increasing dietary protein level from 35 to 55% at the same dietary lipid level. At the same dietary lipid content, WG and SGR obtained with diets containing 55% protein was significantly higher than those obtained with diets containing 45 and 35% protein. No significant effect on growth rate was found when the dietary level of lipid was increased from 7 to 14%. While the levels of protein and lipid in the diets had no significant effect on feed intake, other nutrient utilization efficiency parameters including daily protein intake (DPI), feed efficiency (FE), and protein efficiency ratio (PER) showed a similar trend to that of growth rates, with the highest values obtained with diets containing 55% protein. Muscle chemical composition was not significantly affected by the different dietary treatments for each dietary lipid or protein level tested. These findings may suggest that a practical diet containing 55% protein and 7% lipid provides sufficient nutrient and energy to support the acceptable growth rates and nutrient utilization of mandarin fish juveniles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Since protein is often the most costly component of the formulated fish feeds, numerous studies have been undertaken to define the optimum dietary protein requirement for developing more cost-effective, nutritionally balanced practical diets for various fish species. However, the optimum dietary protein requirements are known to be affected by several factors including the fish species and size, the quality of the protein source, and the amount of non-protein energy in the diet (NRC 2011). When insufficient non-protein energy is available in the diet, part of the dietary protein will be catabolized to supply energy, which is wasteful. Thus, dietary supplementation of energy-yielding nutrients, mainly lipids, has been suggested as a strategy to spare or improve the efficiency of protein utilization by fish, thereby enhancing economic returns and reducing water pollution. Conversely, supply of dietary lipid in excess of requirement can limit feed consumption, thereby reducing the intake of the necessary amount of protein and other essential nutrients for maximal growth rates of fish while enhancing body fat deposition. Therefore, it is very important to determine the optimal dietary balance between protein and lipid for achieving maximum growth and efficient feed utilization of fish.

Golden mandarin fish, Siniperca scherzeri, is one of the most commercially important freshwater species endemic to East Asia, mainly distributed in China, Korea, and Northern Vietnam (Zhou et al. 1988). Increased market demands combined with the dramatic decline in wild stocks as a result of over-catching and habitat destruction (Liang 1996; Wu et al. 1997) has created considerable interest in the development and improvement of culture practices for commercial production of this species. In fact, mandarin fish has become one of the most promising target species with high potential for aquaculture due to its excellent taste, high market value, rapid growth, and high resistance against disease. However, despite the commercial importance of mandarin fish, no commercial formulated feed is yet available for this species, and fish reared in commercial pens are usually fed live feed. Since live feed production is not cost-effective, feeding live prey to mandarin fish may hinder the prospective development of extensive commercial production of this species. Therefore, it is necessary to develop formulated feeds for mandarin fish culture to be far more practical and efficient in terms of commercial operation cost compared with the present practice of using live feed as the rearing diet. In fact, the present study is believed to be the first attempt to evaluate the effects of dietary protein and lipid levels in practical feeds on growth performance, feed utilization, and muscle composition of juvenile mandarin fish, S. scherzeri. The results of the current study could be helpful in formulating a cost-effective and nutritionally sound practical diet for this species.

Methods

Experimental diets

Formulation and proximate composition of the experimental diets are provided in Table 1. Six experimental diets were formulated to contain three protein levels (35, 45, and 55% crude protein) each at two lipid levels (7 and 14% crude lipid). Anchovy fish meal served as the main protein source and equal proportions of squid liver oil and soybean oil as lipid sources in the experimental diets. All dried ingredients were well-mixed and, after addition of oil and double-distilled water, pelleted through a meat chopper machine. The pellets were dried overnight at room temperature, crushed into suitable size (3 mm in diameter), and stored at −30 °C until used.

Fish and feeding trial

Juvenile mandarin fish were kindly provided by Dr. Yi Oh Kim (Inland Fisheries Research Institute, Chungcheongbuk-do, South Korea). A commercial feed (50% crude protein and 13% lipid; Woosung, Daejeon, South Korea) was ground to a fine powder and sieved through a 2–3-mm mesh screen. Then it was pelletized into 1.5–1.8-mm long cylindrical pellets having a diameter of 3 mm. Fish were fed the repelleted commercial diet for 2 weeks to be acclimated to the experimental conditions and facilities. Following the acclimation period, fish (initial mean body weight, 8.3 ± 0.1 g) were distributed in a closed recirculation system equipped with 18 square glass aquaria of 65 L capacity at a density of 20 fish per aquarium. Each aquarium was supplied with dechlorinated freshwater at a flow rate of 1.5 L min−1 and continuous aeration. The photoperiod was maintained on a 12:12-h (light/dark) schedule. The average water temperature during the feeding trial was 23 ± 0.7 °C. Triplicate groups of fish were fed with one of the test diets to visual satiation twice a day (09:00 and 17:00 h) for 8 weeks. The uneaten feed was collected, dried, and weighted to determine the feed intake level.

At the end of the feeding trial, all the fish in each tank were counted and bulk-weighed for calculation of survival, growth, and feed utilization parameters including weight gain (WG), specific growth rate (SGR), feed efficiency (EF), daily feed intake (DFI), daily protein intake (DEI), and protein efficiency ratio (PER) through the following formulas:

Five fish per tank were randomly sampled and stored at −45 °C for muscle proximate composition analyses. The proximate composition of the experimental diets and muscle samples of fish were analyzed according to standard methods (AOAC 1997). The crude protein content was determined using the Auto Kjeldahl System (Buchi, Flawil, Switzerland), the crude lipid content by the ether-extraction method, using a Soxhlet extractor (VELP Scientifica, Milano, Italy), the moisture content by oven drying (105 °C for 6 h), and the ash content using a muffler furnace (600 °C for 4 h).

Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to two-way ANOVA to test for differences in the mean effects of dietary protein and lipid levels, using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05. Data were presented as mean ± SE. Percentage data were arcsine transformed before statistical analysis.

Results

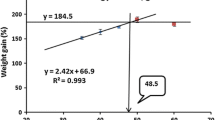

The increase of dietary protein level from 35 to 55% induced a significant increase in fish growth performance in terms of WG and SGR (Table 2). Fish fed diets with 55% protein had significantly higher growth rate than those fed the 35 and 45% protein, regardless of dietary lipid level. Although fish growth performance was not significantly affected by dietary lipid content, numerically higher values were observed in fish offered the diet with the highest lipid content (14%). While DFI was not affected by the dietary treatment, significantly higher DPI was found in fish fed the diets containing 55% protein compared to those fed the 45% protein or less. Fish fed the 55% protein diet showed significantly higher feed efficiency than those given lower protein at both dietary lipid levels. PER was significantly increased with increasing dietary protein from 35 to 55%, and the highest value was recorded in fish fed the P55L14 diet. However, dietary lipid contents had no significant effect on feed utilization efficiency of juvenile mandarin fish at all the dietary protein levels.

Two-way ANOVA revealed that neither dietary protein and lipid levels alone nor their interactions had significant effect (P > 0.05) on muscle composition of juvenile mandarin fish after 8 weeks of feeding (Table 2).

Discussion

In the present study, growth performance of juvenile mandarin fish, in terms of weight gain (WG) and specific growth rate (SGR), was significantly increased with the increase in dietary protein level and the highest values were observed in those fed the highest dietary protein level of 55% (Table 3). This value fits within the range of those reported in previous studies for other strictly carnivorous fish species, such as yellow snapper, Lutjanus argentiventris (Peters 1869) (Maldonado-García et al. 2012), Senegalese sole, Solea senegalensis (Rema et al. 2008), Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus, L.) (Hamre et al. 2003), common dentex, Dentex dentex (Espinos et al. 2003), Murray cod, Maccullochella peelii peelii (De Silva et al. 2002), and Mediterranean yellowtail, Seriola dumerilii (Jover et al. 1999) that generally have high dietary requirements for protein (Wilson 2002; NRC 2011). Since growth performance did not reach a plateau over the tested protein levels in the present study and fish fed the diets containing 55% protein exhibited higher growth rates than those fed the diet containing dietary protein of 35 and 45%, it could be suggested that mandarin fish juveniles require dietary protein of at least 55% to sustain their fast growth. Nevertheless, further research is needed to precisely define the optimal dietary protein requirement for desirable rate of growth using diets containing higher levels of protein than 55%.

In addition, although increased dietary protein levels had no significant effect on DFI in the present study, it resulted in significantly higher FE and PER values. This meant that fish fed the high-protein diets (45 to 55% dietary protein) used dietary protein more efficiently than fish fed the low-protein diet (35%). A similar trend has also been found by different authors for other freshwater carnivorous fish species including pikeperch, Sander lucioperca (Nyina-wamwiza et al. 2005), and snakehead (Aliyu-Paiko et al. 2010). Higher pressure on body protein in order to satisfy the dietary needs for tissue building, repair, and metabolism has been suggested as the reason for poor growth and dietary utilization observed in fish fed sub-optimal dietary protein levels (Mohanta et al. 2013).

Dietary energy has a major impact on the dietary protein requirements of fish, and by proper use of non-protein energy sources, particularly lipid, dietary protein in fish feed can be spared (Mohanta et al. 2013). Nevertheless, a protein-sparing effect, where supplementation of dietary lipid improves fish performance and feed utilization efficiency, was not evident in this study at all protein levels. Although numerically higher values were observed in those of fish fed 14% dietary lipid, there was no significant difference in weight gain and PER of fish fed diets containing 7 to 14% lipid. These results may suggest that 7% dietary lipid is probably sufficient to meet the minimal requirement of this fish while the amount of dietary lipid needed to achieve maximum growth seems to be at or close to 14%. Limited or no obvious protein-sparing effect was also observed in various other fish species including murray cod, Maccullochella peelii peelii (De Silva et al. 2002), grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella (Du et al. 2005), white seabream, Diplodus sargus (Ozorio et al. 2006), and tiger puffer, Takifugu rubripes (Kikuchi et al. 2009), where increasing levels of dietary lipid had no beneficial effects on growth and feed utilization efficiency.

In the present study, muscle chemical composition was not affected by dietary treatment. Similar results were recorded for Senegalese sole, Solea senegalensis Kaup, (Valente et al. 2011) Mediterranean yellowtail, Seriola dumerili (Vidal et al. 2008), Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua L. (Morais et al. 2001), and red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus L. (McGoogan and Gatlin 1999). This finding is in contrast to those reported in other studies for Totoaba, Totoaba macdonaldi (Rueda-López et al. 2011), topmouth culter, Culter alburnus Basilewsky (Zhang et al. 2015), and red porgy, Pagrus pagrus, (Schuchardt et al. 2008) where fish muscle composition was significantly affected by dietary protein/lipid ratios. This discrepancy may be attributed to the fish species variation or a difference in experimental condition particularly dietary protein/energy ratios.

Conclusion

Despite the growing importance of the mandarin fish as a promising target species with high potential for aquaculture, there is no information concerning the nutritional requirement of this freshwater finfish species. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to evaluate the protein and lipid requirements of this fish indicating that diets for juvenile mandarin fish should include at least 55% protein and 7% lipid to maintain a good performance. These findings may provide useful context for developing a more cost-effective and nutritionally balanced feed for the culture of mandarin fish.

Abbreviations

- WG:

-

Weight gain

- SGR:

-

Specific growth rate

- DPI:

-

Daily protein intake

- FE:

-

Feed utilization

- PER:

-

Protein efficiency ratio

References

Aliyu-Paiko M, Hashim R, Shu-Chien AC. Influence of dietary lipid/protein ratio on survival, growth, body indices and digestive lipase activity in snakehead (Channa striatus, Bloch 1793) fry reared in re-circulating water system. Aquacult Nutr. 2010;16:466–74.

AOAC (Association of Official Analytical Chemists). Official Methods of Analysis. 16th ed. Arlington: Association of Official analytical chemists; 1997.

De Silva SS, Gunasekera RM, Collins RA, Ingram BA. Performance of juvenile Murray cod, Maccullochella peelii peelii (Mitchell), fed with diets of different protein to energy ratio. Aquacult Nutr. 2002;8:79–85.

Du ZY, Liu YJ, Tian LX, Wang JT, Wang Y, Liang GY. Effects of dietary lipid level on growth, feed utilization and body composition by juvenile grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquacult Nutr. 2005;11:139–46.

Espinos FJ, Tomas A, Perez LM, Balasch S, Jover M. Growth of dentex fingerlings (Dentex dentex) fed diets containing different levels of protein and lipid. Aquaculture. 2003; 218: 479–490.

Hamre K, Øfsti A, Næss T, Nortvedt R, Holm JC. Macronutrient composition of formulated diets for Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus, L.) juveniles. Aquaculture. 2003;227:233–44.

Jover M, Garcıa-Gomez A, Tomas A, De la Gandara F, Perez L. Growth of mediterranean yellowtail (Seriola dumerilii) fed extruded diets containing different levels of protein and lipid. Aquaculture. 1999; 179: 25–33.

Kikuchi K, Furuta T, Iwata N, Onuki K, Noguchi T. Effect of dietary lipid levels on the growth, feed utilization, body composition and blood characteristics of tiger puffer Takifugu rubripes. Aquaculture. 2009;298:111–7.

Liang XF. Study on mandarin fish and its culture home and abroad. Fisheries Sci Tech Inform. 1996;23:13–7 (in Chinese).

Maldonado-García M, Rodríguez-Romero J, Reyes-Becerril M, Álvarez-González CA, Civera-Cerecedo R, Spanopoulos M. Effect of varying dietary protein levels on growth, feeding efficiency, and proximate composition of yellow snapper Lutjanus argentiventris (Peters, 1869). Lat Am J Aquat Res. 2012;40:1017–25.

McGoogan BB, Gatlin DM. Dietary manipulations affecting growth and nitrogenous waste production of red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus I Effects of dietary protein and energy levels. Aquaculture. 1999;178:333–48.

Mohanta KN, Subramanian S, Korikanthimath VS. Effect of dietary protein and lipid levels on growth, nutrient utilization and whole-body composition of blue gourami, Trichogaster trichopterus fingerlings. J Anim Physiol An N. 2013;97:126–36.

Morais S, Bell JG, Robertson DA, Roy WJ, Morris PC. Protein/lipid ratios in extruded diets for Atlantic cod Gadus morhua L.: effects on growth, feed utilisation, muscle composition and liver histology. Aquaculture. 2001;203:101–19.

NRC (National Research Council). Nutrient requirements of fish and shrimp. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2011. 392 pp.

Nyina-wamwiza L, Xu XL, Blanchard G, Kestemont P. Effect of dietary protein, lipid and carbohydrate ratio on growth, feed efficiency and body composition of pikeperch Sander lucioperca fingerlings. Aquac Res. 2005;36:486–62.

Ozorio ROA, Valente LMP, Pousao-Ferreira P, Oliva-Teles A. Growth performance and body composition of white seabream (Diplodus sargus) juveniles fed diets with different protein and lipid levels. Aquac Res. 2006;37:255–63.

Rema P, Conceicao LEC, Evers F, Castro-Cunha M, Dinis MT, Dias J. Optimal dietary protein levels in juvenile Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). Aquacult Nutr. 2008;14:263–9.

Rueda-López S, Lazo JP, Reyes GC, Viana MT. Effect of dietary protein and energy levels on growth, survival and body composition of juvenile Totoaba macdonaldi. Aquaculture. 2011;319:385–90.

Schuchardt D, Vergara JM, Fernandez-Palacios H, Kalinowski CT, Hernandez- Cruz CM, Izquierdo MS, Robaina L. Effects of different dietary protein and lipid levels on growth, feed utilization and body composition of red porgy (Pagrus pagrus) fingerlings. Aquacult Nutr. 2008;14:1–9.

Valente LMP, Linares F, Villanueva JLR, Silva JMG, Espe M, Escórcio C, Pires MA, Saavedra MJ, Borges P, Medale F, Alvárez-Blázquez B, Peleteiro JB. Dietary protein source or energy levels have no major impact on growth performance, nutrient utilization or flesh fatty acids composition of market-sized Senegalese sole. Aquaculture. 2011;318:128–37.

Vidal AT, Garcia FDG, Gomez AG, Cerda MJ. Effect of the protein/energy ratio on the growth of Mediterranean yellowtail (Seriola dumerili). Aquac Res. 2008;39:1141–8.

Wilson RP. Amino acid and proteins. In: Halver JE, Hardy RW, editors. Fish nutrition. New York: Academic Press; 2002. p. 143–79.

Wu LX, Jiang ZQ, Qin KJ. Feeding habit and fishery utilization of Siniperca scherzeri in Biliuhe reservoir. J Fish Sci Chin. 1997;44:25–9 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Zhang YL, Song L, Liu RP, Zhao ZB, He H, Fan QX, Shen ZG. Effects of dietary protein and lipid levels on growth, body composition and flesh quality of juvenile topmouth culter, Culter alburnus Basilewsky. Aquac Res. 2015;47:2633–41.

Zhou CW, Yang Q, Cai DL. On the classification and distribution of the Sinipercinae fishes (Family Serranidae). Zool Res. 1988;9:113–26 (in Chinese with English abstract).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Fishery Commercialization Technology Development Program (D11524615H480000120) funded by Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Fishery Commercialization Technology Development Program (D11524615H480000120). The funding organization played an active role in the manufacturing of the experimental diets and analyses.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

ZS and SKH manufactured the experimental feed and drafted the manuscript. YOK conducted the feeding trial and performed the analyses. SML conceived and designed the study and experimental facility, and also revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experimental protocols followed the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Gangneung-Wonju National University.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sankian, Z., Khosravi, S., Kim, YO. et al. Effect of dietary protein and lipid level on growth, feed utilization, and muscle composition in golden mandarin fish Siniperca scherzeri . Fish Aquatic Sci 20, 7 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41240-017-0053-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41240-017-0053-0