Abstract

Analysis of various genetically modified mice, with supernumerary teeth, has revealed the following two intrinsic molecular mechanisms that increase the number of teeth. One plausible explanation for supernumerary tooth formation is the rescue of tooth rudiments. Topical application of candidate molecules could lead to whole tooth formation under suitable conditions. Congenital tooth agenesis is caused by the cessation of tooth development due to the deletion of the causative gene and suppression of its function. The arrest of tooth development in Runx2 knockout mice, a mouse model of congenital tooth agenesis, is rescued in double knockout mice of Runx2 and Usag-1. The Usag-1 knockout mouse is a supernumerary model mouse. Targeted molecular therapy could be used to generate teeth in patients with congenital tooth agenesis by stimulating arrested tooth germs. The third dentition begins to develop when the second successional lamina is formed from the developing permanent tooth in humans and usually regresses apoptotically. Targeted molecular therapy, therefore, seems to be a suitable approach in whole-tooth regeneration by the stimulation of the third dentition. A second mechanism of supernumerary teeth formation involves the contribution of odontogenic epithelial stem cells in adults. Cebpb has been shown to be involved in maintaining the stemness of odontogenic epithelial stem cells and suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Odontogenic epithelial stem cells are differentiated from one of the tissue stem cells, enamel epithelial stem cells, and odontogenic mesenchymal cells are formed from odontogenic epithelial cells by epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Both odontogenic epithelial cells and odontogenic mesenchymal cells required to form teeth from enamel epithelial stem cells were directly induced to form excess teeth in adults. An approach for the development of targeted therapeutics has been the local application of monoclonal neutralizing antibody/siRNA with cationic gelatin for USAG-1 or small molecule for Cebpb.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The development of preemptive medicine, to extend healthy life expectancy in a super-aging society, is an important aspect of Japan’s medical strategy. “Eating” to improve oral frailty has been adopted, and the importance of dental treatment has been highlighted. Many instances of missing teeth can be attributed to acquire causes such as dental caries and periodontal disease, whereas congenital causes include congenital edentulous disease with a high incidence at 1% [1].

The basic treatment for missing teeth is prosthetic replacement with dental implants or dentures. These prosthetic treatments have been traditionally used and are still being used and further developed at present. Preemptive medicine for tooth regeneration is expected to become incorporated into clinical practice. Studies of tooth regeneration using tissue engineering approaches have been reported. Various cells such as stem cells are used as a cell source. In addition, to make teeth in vitro [2], the “organ germ method” has been reported, which is a cell manipulation technology that regenerates the organ primordium of the tooth in a collagen gel [3]. However, all current tissue engineering approaches have problems, such as the cost and safety of the cell source and concerns regarding the potential for contamination or tumorigenicity, and thus, they have not yet reached readiness for clinical applications. Further to this, antibody drugs, which are molecularly targeted drugs, are being developed not only for cancer but also for various other diseases. Patisiliane, an siRNA, is currently being investigated as a drug for familial amyloidosis [4]. By combining genomic analysis, epidemiological research, and mouse model studies, we have consistently aimed to regenerate teeth by controlling the number of teeth using molecular approaches, from gene therapy with viral vectors, to targeted molecular therapy with antibody- or siRNA-based drugs.

Humans are diphyodonts and have both residual and permanent teeth, including incisors and premolars. Rodents, such as mice, have a retarded number of teeth, with only one incisor and three molars, and as monophyodonts they have no residual teeth. Similar to many other organs, the number of teeth is strictly controlled within each species [5]. Analysis of various knockout mice with supernumerary teeth has revealed the following two intrinsic molecular mechanisms that increase the number of teeth [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]: (1) rescue of rudimental tooth germs and (2) contribution of odontogenic epithelial stem cells (OESCs).

In this article, we will introduce recent advances in research regarding these two mechanisms and discuss the potential of tooth regeneration with targeted molecular therapy, alongside descriptions of target molecules.

Main text

Rescue of rudimental tooth germs

Mice, unlike humans, have one incisor and three molars that are separated by a tooth formation-free region called the diastema. Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for the formation of supernumerary teeth in mice [14, 16, 17]. One plausible explanation for supernumerary tooth formation is the rescue of tooth rudiments in the diastema or maxillary deciduous incisors [14, 18,19,20]. Most reported mouse supernumerary teeth are located in the diastema region. This is the rescue of vestigial tooth rudiments. During the early stages of tooth development, many transient vestigial dental buds develop in the diastema area. Some of them can develop into the bud stage, but later regress and disappear by apoptosis, or merge with the mesial crown of the first molar tooth [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Major signaling pathways regulating tooth development are also expressed in these vestigial dental buds. A number of mutant mouse strains have been reported to exhibit supernumerary diastema teeth. Although rudimentary tooth buds form in the embryonic diastema, they regress apoptotically [27]. Transgenic mice in which the keratin 14 promoter directs ectodysplasin (Eda) or Eda receptor expression to the epithelium had supernumerary teeth mesial to the first molar as a result of diastema tooth development [28,29,30]. It is also reported that Sprouty2 (Spry2)- or Spry4-deficient mice develop supernumerary teeth as a result of diastema tooth development [31]. Usag-1 is a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonist [32]. We have previously demonstrated that inhibition of apoptosis can lead to successive development of rudimentary maxillary incisors in Usag-1 null mice [16]. Furthermore, increased BMP signaling is observed in Usag-1-deficient mice, which prevents apoptosis and leads to the development of supernumerary teeth [14]. These results suggest that inactivation or inhibition of single candidate molecules such as Usag-1 has the potential to regenerate whole teeth through the rescue of the rudimental tooth germ. Furthermore, we have previously claimed that gene interactions between BMP-7 and Usag-1 regulate supernumerary maxillary incisor formation [12]. BMP-7 co-localizes with Usag-1 in the area of the maxillary rudiment incisor tooth germ, as well as the regular maxillary incisor tooth organ. We previously confirmed that increased BMP signaling in supernumerary teeth of Usag-1 deficient mice could be prohibited by BMP-7 abrogation. Using subrenal capsule transplantation of embryonic day 15 (E15) maxillary incisor tooth primordia supplemented to BMP-7 with cationic gelatin demonstrated rescue of tooth rudiments and supernumerary tooth development in both Usag-1+/− and Usag-1−/− mice. Based upon these results, we claimed that Usag-1 functions as an antagonist of BMP-7 and that topical application of the candidate molecule could make a whole tooth under the correct conditions [12].

Many genes responsible for congenital tooth agenesis have been identified, and many are common in humans and mice [33]. Mouse model studies have demonstrated that congenital tooth agenesis is caused by the cessation of tooth development halfway through the process due to the deletion of the causative gene and suppression of its function. For example, RUNX2, MSX1, EDA, WNT10A, PAX9, and AXIN2 are known to be responsible for congenital tooth agenesis [34,35,36,37]. However, the majority of patients with congenital edentulous disease have causative mutations in WNT10A [38, 39]. EDA is a causative gene of anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, which is a representative disease of syndromic congenital edentulous disease [40]. Runx2−/− mice exhibit stunted tooth formation [37], and patients with a unique Arg131Cys missense RUNX2 mutation develop a novel dental phenotype; i.e., they have no supernumerary teeth but one congenitally missing tooth [41]. In double null Usag-1−/−/Runx2−/− mice, three interesting phenomena were observed: the prevalence of supernumerary teeth was lower than in Usag-1 null mice; tooth development progressed further compared to Runx2 null mice; and the frequency of molar lingual buds was lower than in Runx2 null mice [9]. Therefore, we suggest that Runx2 and Usag-1 act in an antagonistic manner [9]. We previously demonstrated that deletion of Usag-1 rescued the hypoplastic and poorly differentiated molar and incisor phenotypes observed in Runx2−/− mice [9]. The rescue of tooth formation in genetically defined mouse models clearly demonstrates the feasibility of inducing de novo tooth formation via the in situ repression of a single targeted gene. Our investigations and related studies clearly validate the hypothesis that de novo repression of target genes, such as Usag-1, can be used to stimulate arrested tooth germs in order to induce new tooth formation in mammals. Conversely, it was reported that Usag-1 abrogation could rescue cleft palate development but not tooth development arrest in Pax9 deficient mice. In the rescued palate phenotype, modulated WNT signaling was observed but no BMP signaling [42]. Small-molecule Wnt agonists also corrected cleft palate in Pax9 deficient mice [43]. However, it is currently unclear whether repression of Usag-1 could universally rescue the effects of other causative genes of congenital tooth agenesis. The rescue of tooth formation in genetically defined mouse models clearly demonstrates the feasibility of inducing de novo tooth formation via the in situ repression of a single targeted gene. Our investigations and related studies clearly validate the hypothesis that de novo repression of target genes, such as Usag-1, could be used to stimulate arrested tooth germs in order to induce new tooth formation in mammals. Indeed, in animal models of EDA deficiency, which is associated with the human disorder hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia which involves hypodontia, the administration of a soluble EDA receptor agonist has been shown to correct many phenotypic abnormalities, including abnormalities of the dentition in mice (primary) and dogs (secondary or permanent) [44,45,46,47].

After a single postnatal systemic administration of recombinant EDA or anti-EDA receptor agonist monoclonal antibody, it was confirmed that all the physiological aspects of missing teeth, such as the number, size, shape, location, and timing of eruption, were restored, and the teeth functioned normally [44, 47]. In fact, lifelong phenotypic correction was achieved after a short course of treatment [44, 47]. In the future, molecular targeted therapies could be used to generate teeth in patients with congenital tooth agenesis by stimulating arrested tooth germs (Fig. 1).

Treatment plan for congenital tooth agenesis. RUNX2, EDA, MSX1, PAX9, AXIN2, and WNT10A have been identified as causative genes for congenital tooth agenesis. The mutation of the causative gene is used as a biomarker, and a neutralizing antibody of USAG-1 or USAG-1 siRNA is administered as a molecularly targeted drug

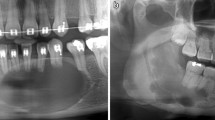

The mechanisms underlying human supernumerary tooth formation have recently become clearer. Deciduous teeth are, ontogenetically, the first generation of teeth. The permanent teeth (except molars) belong to the second dentition. The term “third dentition” refers to the opinion that one more set of teeth can occur in addition to the permanent teeth [48, 49]. The third dentition begins to develop when the second successional lamina is formed from the developing permanent tooth in humans and usually regresses apoptotically like the rudimental incisor of the mouse (Fig. 2). It typically does not completely form the tooth structure [48, 49]. Recently, it was suggested that supernumerary teeth result from the rescue of the third dentition’s regression in humans [49,50,51]. Radiographic examination of tooth development in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia performed over several years suggests that a part of the third dentition may cause the condition [52]. Clinical criteria for supernumerary teeth derived from the third dentition are as follows: (1) the supernumerary tooth is located on the lingual side of permanent teeth, (2) the supernumerary tooth develops after permanent teeth formation, and (3) the shape of the supernumerary tooth is similar to that of the preceding teeth [53, 54]. We have previously reported that this clinical definition would apply to at least one-third of non-syndromic multiple supernumerary teeth [54]. Recently, our investigation evaluated the proportion of collected general supernumerary teeth cases that evinced a third dentition based on the clinical definition of supernumerary teeth derived from the third dentition [55]. The frequency of supernumerary teeth considered to have been derived from the third dentition was 26 out of 78 cases [55]. Evidence of a third dentition was especially apparent in the premolar region, was more common in men, and more likely to occur in patients with three or more supernumerary teeth [55]. It was suggested that the third dentition is the main cause of supernumerary teeth in humans. Our investigation demonstrated that the third dentition, possibly underlain by genetic factors, is a major cause of supernumerary teeth in humans—especially multiple supernumerary teeth [55]. The timing of appearance of the third dentition appears to be after birth [48], meaning that we have a chance to access its formation directly in the mouth. The duration of tooth regeneration by stimulation of the third dentition is almost the same as that of permanent tooth development, according to the clinical case of tooth regeneration by stimulation of the third dentition (Fig. 3). The third dentition has the potential to erupt following permanent teeth eruption without dental caries and periodontal disease (Fig. 3). We can utilize the healthy newly formed teeth for usual dental treatments, such as tooth extraction, orthodontic treatment, and tooth transplantation. Therefore, molecularly targeted therapy seems to be a suitable approach in whole-tooth regeneration by stimulation of the third dentition (Fig. 3).

Tooth regeneration by stimulation of the third dentition. a This treatment involves regenerating the third dentition following permanent teeth eruption by locally administering a neutralizing antibody or siRNA with DDS like cationic gelatin hydrogel for USAG-1. b Frontal section of a computerized tomography (CT) scan of the tooth germ of the third dentition located in the lingual side of the lower right premolar that is preceding the permanent molar in an 11-year-old individual. The yellow arrow indicates the tooth germ of the third dentition. c Occlusal view and frontal section of a CT scan of the erupted third dentition in an 18-year-old individual. The white arrows indicate the erupted third dentition

Contribution of OESCs

A second mechanism of ST formation involves the contribution of OESCs, whereas multiple other mechanisms based on mouse models have been developed [49, 50]. Sox2 is a molecular marker of OESs in mice [56], and Sox2-positive OESCs reportedly contribute to supernumerary tooth formation in mice [6, 57]. We previously demonstrated that Cebpb deficiency is related to the formation of supernumerary teeth. A total of 66.7% of Cebpb−/− 12-month-old animals presented supernumerary teeth and/or odontomas [13]. There were significantly fewer Sox2-positive cells in the labial cervical loop epithelium of adult Cebpb−/− mouse incisors than in wild-type animals [6]. These findings suggest that Cebpb maintains Sox2-positive OESCs in the labial cervical loop epithelium during postnatal life. Differentiated ameloblasts in the maxillary incisor were deranged and lost their cell polarity in adult Cebpb+/+/Runx2+/− animals [6]. Furthermore, the disappearance of the apical-basal polarity of differentiated ameloblasts was visible in Cebpb−/−/Runx2+/+ and Cebpb−/−/Runx2+/− mice, consistent with the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process [58]. Thus, based on these morphological changes, we suggest that Cebpb and Runx2 knockdown contributes to EMT in odontogenic epithelial cells of the maxillary incisor. Taken together, supernumerary tooth formation around the labial cervical loop epithelium of adult maxillary incisors may be dependent on both Cebpb knockdown-induced loss of stemness in OESCs and EMT of odontogenic epithelial cells in Runx2+/− and/or Cebpb−/− mice [6]. In Runx2 heterozygous and null mice, budding was observed in maxillary incisors at E15. Both Runx2 mutants displayed lingual buds in front of the maxillary molars, which are in line with Runx2 preventing the formation of buds for successional teeth [59, 60]. There is a difference between the phenotypes of OESCs in Cebpb−/−/Runx2+/+ and Cebpb−/−/Runx2+/− incisors between E15 and adult animals. No buddings were observed at E15 in Cebpb−/− mice but were seen at E15 in Cebpb+/+/Runx2+/− and Cebpb−/−/Runx2+/− mice, before disappearing on postnatal day 7 [6]. Meanwhile, some adult Cebpb−/− mice possess an unusual incisor that presented ectopic hyperplasia of enamel and dentin in the periapical tissue. Moreover, 33% of 3-month-old Cebpb−/−/Runx2+/− mice had aberrant incisors, characterized by developing or mature ectopic supernumerary teeth in the periapical tissue and dental pulp [8]. Indeed, in humans, supernumerary teeth are less common in the deciduous dentition (first generation of teeth) than in the permanent dentition (second generation of teeth) [61]. In mice, the difference may be linked to stem cell aging in the incisor. Common contributing factors of aging in different organisms, but particularly in mammals, are genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication [62]. As another example of epithelial-mesenchymal interactions, hair graying is the most obvious sign of aging in mammals. Irreparable DNA damage, as that caused by ionizing radiation, abolishes the renewal of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in mice and results in hair graying inasmuch as it also triggers MSC differentiation into mature melanocytes in the niche [63]. The hallmarks of OESCs can change according to aging.

Studies show that conditional knockout of the Apc-gene results in the development of supernumerary teeth in mice [64,65,66]. Notably, adult oral tissues, particularly in young adults, are still responsive to loss of Apc [17]. In old adult mice, supernumerary teeth can be induced on both the labial and lingual sides of the incisors, which contain adult stem cells supporting the continuous growth of mouse incisors [17, 66]. In young mice, supernumerary tooth germs were induced in multiple regions of the jaw, in both incisor and molar regions. They could form directly from the oral epithelium, in the dental lamina connecting the developing molar or incisor tooth germ to the oral epithelium, in the crown region, as well as in the elongating and furcation area of the developing root [67]. Canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling and its downstream molecule Lef-1 are essential for tooth development [68]. Overexpression of Lef-1 under control of the K14 promoter in transgenic mice develops abnormal invaginations of the dental epithelium in the mesenchyme and forms tooth-like structures [69]. De novo supernumerary teeth arising directly from the primary tooth germ or dental lamina have been reported in Apc loss-of-function or β-catenin gain-of-function mice. It was demonstrated that mouse tooth buds expressing stabilized β-catenin give rise to extra tooth formation [65].

Furthermore, SOX2-positive OESCs are reportedly related to several different odontogenic diseases in humans [57, 70, 71]. We also investigated the association between supernumerary teeth and SOX2-positive OESCs and found that some instances of human supernumerary teeth, except those derived from the third dentition, were caused by Sox2-positive OESC, as was observed in Cebpb and Runx2 double knock-out mice [6]. However, it may be possible that OESCs contribute to supernumerary tooth formation in general. Tooth development is under genetic control and is the result of reciprocal and reiterative signaling between the oral ectoderm-derived dental epithelium and cranial neural crest cell-derived dental mesenchyme [72]. Two different cell types (epithelial and mesenchymal) are necessary and essential for whole-tooth regeneration. OESCs have the potential to differentiate odontoblasts by loss of stemness and EMT and regenerate de novo whole teeth (supernumerary teeth) by ectomesenchymal abrogation of Cebpb (Fig. 4). In recent years, there have been many studies of stem cells in relation to the development of regenerative therapies for various organs such as nephrons (the functional units of the kidney) or the pituitary gland [73, 74]. We also demonstrated that OESCs may contribute to supernumerary teeth formation in cases not caused by third dentitions [55]. Multiple supernumerary teeth derived from odontogenic epithelial stem cells have the potential to erupt following the eruption of permanent teeth without dental caries and periodontal disease (Fig. 4). We can utilize the healthy newly formed teeth for usual dental treatments. OESCs are suitable for molecular targeted therapy for whole-tooth regeneration using Cebpb (Fig. 4).

Development of tooth regenerative medicine targeting odontogenic epithelial stem cells. a Cebpb is involved in maintaining the stemness of enamel epithelial stem cells and suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Odontogenic epithelial stem cells (OESCs) are differentiated from one of the tissue stem cells; enamel epithelial stem cells and odontogenic mesenchymal cells are formed from odontogenic epithelial cells by EMT. It was demonstrated that both odontogenic epithelial cells and odontogenic mesenchymal cells, required to form teeth from enamel epithelial stem cells, were directly induced to form excess teeth. b Occlusal view of erupted multiple supernumerary teeth derived from odontogenic epithelial stem cells. The yellow arrows indicate the erupted multiple supernumerary teeth

Conclusions

One plausible explanation for supernumerary tooth formation is the rescue of tooth rudiments. Congenital tooth agenesis is caused by the cessation of tooth development due to the deletion of causative genes and suppression of their function. Molecular targeted therapy could be used to generate teeth in patients with congenital tooth agenesis by stimulating arrested tooth germs. The third dentition begins to develop when the second successional lamina is formed from the developing permanent tooth in humans. Molecularly targeted therapy therefore seems to be a suitable approach in whole-tooth regeneration by the stimulation of the third dentition. A second mechanism of supernumerary tooth formation involves the contribution of OESCs. Cebpb has been shown to be involved in maintaining the stemness of OESCs and suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition in adults. OESCs are differentiated from one of the tissue stem cells, enamel epithelial stem cells, and odontogenic mesenchymal cells are formed from odontogenic epithelial cells by EMT. A major approach for the development of targeted therapeutics has been the local application of monoclonal neutralizing antibodies or siRNAs with cationic gelatin for Usag-1 or small molecule for Cebpb. However, for future clinical applications, further safety studies investigating the toxicity, teratogenicity, and tumorigenicity of these therapeutic molecules need to be performed.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- OESC:

-

Odontogenic epithelial stem cell

- E15:

-

Embryonic day 15

- MSC:

-

Mesenchymal stem cell

References

Ardakani FE, Sheikhha M, Ahmadi H. Prevalence of dental developmental anomalies: a radiographic study. Community Dent Health. 2007;24:140–4.

Ohazama A, Modino S, Miletich I, Sharpe P. Stem-cell-based tissue engineering of murine teeth. J Dent Res. 2004;83:518–22.

Nakao K, Morita R, Saji Y, Ishida K, Tomita Y, Ogawa M, et al. The development of a bioengineered organ germ method. Nat Methods. 2007;4:227–30.

Adams D, Gonzalez-Duarte A, O’Riordan WD, Yang C-C, Ueda M, Kristen AV, et al. Patisiran, an RNAi therapeutic, for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:11–21.

Hillson S. Teeth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986.

Saito K, Takahashi K, Huang B, Asahara M, Kiso H, Togo Y, et al. Loss of Stemness, EMT, and supernumerary tooth formation in Cebpb−/−Runx2 /− murine incisors. Sci Rep. 2018;8.

Saito K, Takahashi K, Asahara M, Kiso H, Togo Y, Tsukamoto H, et al. Effects of Usag-1 and Bmp7 deficiencies on murine tooth morphogenesis. BMC Dev Biol. 2016;16.

Asahara M, Saito K, Kishida T, Takahashi K, Bessho K. Unique pattern of dietary adaptation in the dentition of Carnivora: its advantage and developmental origin. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2016;283:20160375.

Togo Y, Takahashi K, Saito K, Kiso H, Tsukamoto H, Huang B, et al. Antagonistic functions of USAG-1 and RUNX2 during tooth development. PLoS One. 2016;11.

Takahashi K, Kiso H, Saito K, Togo Y, Tsukamoto H, Huang B, Bessho K. Feasibility of Molecularly targeted therapy for tooth regeneration: New Trends in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. In: official book of the Japanese Society of Regenerative Medicine, In Tech, Rijeka, Croatia, 2014. p. 55-65.

Huang B, Takahashi K, Jennings EA, Pumtang-On P, Kiso H, Togo Y, et al. Prospective signs of cleidocranial dysplasia in Cebpb deficiency. J Biomed Sci. 2014;21:44.

Kiso H, Takahashi K, Saito K, Togo Y, Tsukamoto H, Huang B, et al. Interactions between BMP-7 and USAG-1 (uterine sensitization-associated Gene-1) regulate supernumerary organ formations. PLoS One. 2014;9.

Huang B, Takahashi K, Sakata-Goto T, Kiso H, Togo Y, Saito K, et al. Phenotypes of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta deficiency: hyperdontia and elongated coronoid process. Oral Dis. 2012;19:144–50.

Murashima-Suginami A, Takahashi K, Sakata T, Tsukamoto H, Sugai M, Yanagita M, et al. Enhanced BMP signaling results in supernumerary tooth formation in USAG-1 deficient mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;369:1012–6.

Takahashi K, Sakata T, Murashima-Suginami A, Tsukamoto H, Kiso H, Bessho K. Tooth regeneration: potential for stimulation of the formation of a third dentition by one gene. Curr Topics Genetics. 2008;3:77–82.

Murashima-Suginami A, Takahashi K, Kawabata T, Sakata T, Tsukamoto H, Sugai M, et al. Rudiment incisors survive and erupt as supernumerary teeth as a result of USAG-1 abrogation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;359:549–55.

Wang X-P, Oconnell DJ, Lund JJ, Saadi I, Kuraguchi M, Turbe-Doan A, et al. Apc inhibition of Wnt signaling regulates supernumerary tooth formation during embryogenesis and throughout adulthood. Development. 2009;136:1939–49.

Yamamotoabc H, Choa S-W, Songa S-J, Hwanga H-J, Leea M-J, Kima J-Y, et al. Characteristic tissue interaction of the diastema region in mice. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:189–98.

Lagronova-Churava S, Spoutil F, Vojtechova S, Lesot H, Peterka M, Klein OD, Peterkova R. The Dynamics of Supernumerary Tooth Development Are Differentially Regulated by Sprouty Genes. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2013;320.

Ahn Y, Sanderson BW, Klein OD, Krumlauf R. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by wise (Sostdc1) and negative feedback from Shh controls tooth number and patterning. Development. 2010;137:3221–31.

Peterková R, Peterka M, Viriot L, Lesot H. Development of the vestigial tooth primordia as part of mouse Odontogenesis. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:120–8.

Peterková R, Lesot H, Viriot L, Peterka M. The supernumerary cheek tooth in tabby/EDA mice—a reminiscence of the premolar in mouse ancestors. Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:219–25.

Peterkova R, Churava S, Lesot H, Rothova M, Prochazka J, Peterka M, et al. Revitalization of a diastemal tooth primordium inSpry2null mice results from increased proliferation and decreased apoptosis. J Exp Zool B Mol Dev Evol. 2009;312B:292–308.

Prochazka J, Pantalacci S, Churava S, Rothova M, Lambert A, Lesot H, et al. Patterning by heritage in mouse molar row development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:15497–502.

Viriot L, Peterková R, Peterka M, Lesot H. Evolutionary implications of the occurrence of two vestigial tooth germs during early Odontogenesis in the mouse lower jaw. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:129–33.

Witter K, Lesot H, Peterka M, Vonesch J-L, Míšek I, Peterková R. Origin and developmental fate of vestigial tooth primordia in the upper diastema of the field vole (Microtus agrestis, Rodentia). Arch Oral Biol. 2005;50:401–9.

Keränen SVE, Kettunen P, Åberg T, Thesleff I, Jernvall J. Gene expression patterns associated with suppression of odontogenesis in mouse and vole diastema regions. Dev Genes Evol. 1999;209:495–506.

Mustonen T, Pispa J, Mikkola ML, Pummila M, Kangas AT, Pakkasjärvi L, et al. Stimulation of ectodermal organ development by Ectodysplasin-A1. Dev Biol. 2003;259:123–36.

Pispa J, Mustonen T, Mikkola ML, Kangas AT, Koppinen P, Lukinmaa P-L, et al. Tooth patterning and enamel formation can be manipulated by misexpression of TNF receptor Edar. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:432–40.

Tucker A, Headon D, Courtney J-M, Overbeek P, Sharpe P. The activation level of the TNF family receptor, Edar, determines cusp number and tooth number during tooth development. Dev Biol. 2004;268:185–94.

Klein OD, Minowada G, Peterkova R, Kangas A, Yu BD, Lesot H, et al. Sprouty genes control diastema tooth development via bidirectional antagonism of epithelial-mesenchymal FGF signaling. Dev Cell. 2006;11:181–90.

Yanagita M, Oka M, Watabe T, Iguchi H, Niida A, Takahashi S, et al. USAG-1: a bone morphogenetic protein antagonist abundantly expressed in the kidney. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316:490–500.

Chhabra N, Goswami M, Chhabra A. Genetic basis of dental agenesis - molecular genetics patterning clinical dentistry. Medicina Oral Patología Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 2014;19:e112–9.

Peters H, Neubuser A, Kratochwil K, Balling R. Pax9-deficient mice lack pharyngeal pouch derivatives and teeth and exhibit craniofacial and limb abnormalities. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2735–47.

Satokata I, Maas R. Msx1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nat Genet. 1994;6:348–56.

Genderen CV, Okamura RM, Farinas I, Quo RG, Parslow TG, Bruhn L, et al. Development of several organs that require inductive epithelial-mesenchymal interactions is impaired in LEF-1-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2691–703.

D'Souza RN, Aberg T, Gaikwad J, Cavender A, Owen M, Karsenty G, et al. Cbfa1 is required for epithelial-mesenchymal interactions regulating tooth development in mice. Development. 1999;126:2911–20.

Machida J, Goto H, Tatematsu T, Shibata A, Miyachi H, Takahashi K, et al. WNT10A variants isolated from Japanese patients with congenital tooth agenesis. Human Genome Variation. 2017;4.

Yu M, Wong SW, Han D, Cai T. Genetic analysis: Wnt and other pathways in nonsyndromic tooth agenesis. Oral Dis. 2018;25:646–51.

Pummila M, Fliniaux I, Jaatinen R, James MJ, Laurikkala J, Schneider P, et al. Ectodysplasin has a dual role in ectodermal organogenesis: inhibition of bmp activity and induction of Shh expression. Development. 2007;134:117–25.

Callea M, Fattori F, Yavuz I, Bertini E. A new phenotypic variant in cleidocranial dysplasia (CCD) associated with mutation c.391C>T of the RUNX2 gene. Case Reports. 2012.

Li C, Lan Y, Krumlauf R, Jiang R. Modulating Wnt signaling rescues palate morphogenesis in Pax9 mutant mice. J Dent Res. 2017;96:1273–81.

Jia S, Zhou J, Fanelli C, Wee Y, Bonds J, Schneider P, et al. Small-molecule Wnt agonists correct cleft palates inPax9mutant micein utero. Development. 2017;144:3819–28.

Gaide O, Schneider P. Permanent correction of an inherited ectodermal dysplasia with recombinant EDA. Nat Med. 2003;9:614–8.

Casal ML, Lewis JR, Mauldin EA, Tardivel A, Ingold K, Favre M, et al. Significant correction of disease after postnatal Administration of Recombinant Ectodysplasin a in canine X-linked ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1050–6.

Mauldin EA, Gaide O, Schneider P, Casal ML. Neonatal treatment with recombinant ectodysplasin prevents respiratory disease in dogs with X-linked ectodermal dysplasia. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:2045–9.

Kowalczyk C, Dunkel N, Willen L, Casal ML, Mauldin EA, Gaide O, et al. Molecular and therapeutic characterization of anti-ectodysplasin a receptor (EDAR) agonist monoclonal antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30769–79.

Ooë T. Epithelial anlagen of human third dentition and their migrations in the mandible and maxilla. Okajimas Folia Anat Jpn. 1969;46:243–51.

Juuri E, Balic A. The biology underlying abnormalities of tooth number in humans. J Dent Res. 2017;96:1248–56.

Wang X-P, Fan J. Molecular genetics of supernumerary tooth formation. Genesis. 2011;49:261–77.

Takahashi K, Kiso H, Saito K, Togo Y, Tsukamoto H, Huang B, et al. Feasibility of gene therapy for tooth regeneration by stimulation of a third dentition. Gene Therapy – Tools and Potential Applications. 2013.

Kreiborg S, Jensen BL. Tooth formation and eruption – lessons learnt from cleidocranial dysplasia. Eur J Oral Sci. 2018;126:72–80.

Sasaki H, Funao J, Morinaga H, Nakano K, Ooshima T. Multiple supernumerary teeth in the maxillary canine and mandibular premolar regions: a case in the postpermanent dentition. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2007;17:304–8.

Takahashi K, Togo Y, Saito K, Kiso H, Huang B, Tsukamoto H, et al. Two non-syndromic cases of multiple supernumerary teeth with different characteristics and a review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofacial Surg Med Pathol. 2016;28:250–4.

Kiso H, Takahashi K, Mishima S, Murashima-Suginami A, Kakeno A, Yamazaki T, et al. Third dentition is the Main cause of premolar supernumerary tooth formation. J Dent Res. 2019;98:968–74.

Juuri E, Jussila M, Seidel K, Holmes S, Wu P, Richman J, et al. Sox2 marks epithelial competence to generate teeth in mammals and reptiles. Development. 2013;140:1424–32.

Juuri E, Isaksson S, Jussila M, Heikinheimo K, Thesleff I. Expression of the stem cell marker, SOX2, in ameloblastoma and dental epithelium. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121:509–16.

Moreno-Bueno G, Portillo F, Cano A. Transcriptional regulation of cell polarity in EMT and cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6958–69.

Åberg T, Cavender A, Gaikwad JS, Bronckers AL, Wang X, Waltimo-Sirén J, et al. Phenotypic changes in dentition of Runx2 homozygote-null mutant mice. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:131–9.

Wang X-P, Åberg T, James M, Levanon D, Groner Y, Thesleff I. Runx2 (Cbfa1) inhibits Shh signaling in the lower but not upper molars of mouse embryos and prevents the budding of putative successional teeth. J Dent Res. 2005;84:138–43.

Ravn JJ. Aplasia, supernumerary teeth and fused teeth in the primary dentition an epidemiologic study. Eur J Oral Sci. 1971;79:1–6.

López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–217.

Inomata K, Aoto T, Binh NT, Okamoto N, Tanimura S, Wakayama T, et al. Genotoxic stress abrogates renewal of melanocyte stem cells by triggering their differentiation. Cell. 2009;137:1088–99.

Kuraguchi M, Wang X-P, Bronson RT, Rothenberg R, Ohene-Baah NY, Lund JJ, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is required for Normal development of skin and thymus. PLoS Genet. 2006;2.

Jarvinen E, Salazar-Ciudad I, Birchmeier W, Taketo MM, Jernvall J, Thesleff I. Continuous tooth generation in mouse is induced by activated epithelial Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:18627–32.

Liu F, Chu EY, Watt B, Zhang Y, Gallant NM, Andl T, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling directs multiple stages of tooth morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;313:210–24.

Huysseune A, Thesleff I. Continuous tooth replacement: the possible involvement of epithelial stem cells. BioEssays. 2004;26:665–71.

Kratochwil K, Dull M, Farinas I, Galceran J, Grosschedl R. Lef1 expression is activated by BMP-4 and regulates inductive tissue interactions in tooth and hair development. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1382–94.

Zhou P, Byrne C, Jacobs J, Fuchs E. Lymphoid enhancer factor 1 directs hair follicle patterning and epithelial cell fate. Genes Dev. 1995;9:700–13.

Lei Y, Jaradat JM, Owosho A, Adebiyi KE, Lybrand KS, Neville BW, et al. Evaluation of SOX2 as a potential marker for ameloblastic carcinoma. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 2014;117.

Xavier GM, Patist AL, Healy C, Pagrut A, Carreno G, Sharpe PT, et al. Activated WNT signaling in postnatal SOX2-positive dental stem cells can drive odontoma formation. Sci Rep. 2015;5.

Thesleff I. The genetic basis of tooth development and dental defects. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140A:2530–5.

Diep CQ, Ma D, Deo RC, Holm TM, Naylor RW, Arora N, et al. Identification of adult nephron progenitors capable of kidney regeneration in zebrafish. Nature. 2011;470:95–100.

Yoshida S, Kato T, Kato Y. EMT involved in migration of stem/progenitor cells for pituitary development and regeneration. J Clin Med. 2016;5:43.

Acknowledgements

We thank all our laboratory members for their assistance.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research [(C):25463081 and 17 K118323].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KT prepared the manuscript. HK, AM-S, YT, MS, YT, and KB reviewed the manuscript. All coauthors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

We obtained consent for the publication and presentation of personal data.

Competing interests

No competing interests associated with this study exist.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Takahashi, K., Kiso, H., Murashima-Suginami, A. et al. Development of tooth regenerative medicine strategies by controlling the number of teeth using targeted molecular therapy. Inflamm Regener 40, 21 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-020-00130-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41232-020-00130-x