Abstract

Background

During a biodiversity survey of Béal an Mhuirthead, Co. Mayo, a small population of Laminaria ochroleuca Bachelot de Pylaie was discovered in a semi-protected cove on the northwest part of the headland among a mixed macroalgal assemblage including the kelps Laminaria digitata and Saccharina latissima. This is the first record of this southern European species in Irish waters.

Methods

Individuals were morphologically identified by their smooth stipes, conical, claw-like holdfasts, broad golden blades and all regions of the thallus were devoid of epibiota. Individual L. ochroleuca were genetically identified using the mitochondrial atp8 gene, and all belonged to the same haplotype previously found in France and Portugal.

Results

Using 12 microsatellite loci, we found 34 alleles from 15 genotyped sporophytes. Multilocus estimates of allelic diversity and expected heterozygosity were comparable to sites sampled in the Iberian Peninsula (0.427 and 0.562 on average respectively) despite strong genetic differentiation between Scots Port and other sites throughout the known European range. There was a general trend of heterozygote excess which may indicate recent admixture following a founder event(s).

Conclusions

The appearance of this southern European kelp species raises many questions including i) how widely distributed it is in Ireland, ii) how it arrived at this northwestern point of the country if it is not widely distributed in Ireland, and iii) whether it can withstand low winter temperatures L. ochroleuca was previously thought not to endure. More detailed surveys in Irish kelp forests should take place to determine the distribution of this kelp and its impact on the Irish kelp forest ecosystem.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kelp forests along European coastlines are composed of stipitate kelps in the Laminariales as well as one member of the Tilopteridales, Saccorhiza polyschides. Most subtidal communities from the United Kingdom (UK) and Ireland northward are dominated by the boreal kelp Laminaria hyperborea (Gunnerus) Foslie (Araújo et al., 2016). In the southern UK, kelp forests include a Lusitanian species, Laminaria ochroleuca Bachelot De la Pylaie, that is found from the lower limit of the intertidal zone down to 18 m, in monospecific or mixed kelp populations at semi-exposed sites. The first record of L. ochroleuca in the UK was in the early twentieth century, either due to increased survey intensity or because the species expanded its distribution (Parke, 1948). Today, the known northern range extends from Brittany, France to its limit in Devon, UK (Araújo et al., 2016; Gayral, 1958; John, 1969), but no L. ochroleuca has been recorded in the Republic of Ireland during previous subtidal or intertidal surveys (Simkanin et al., 2005; Picton & Morrow, 2006).

Laminaria hyperborea and L. ochroleuca are easily distinguished through morphological features, especially the rugosity of L. hyperborea stipe and fouling throughout the thallus (Bunker et al., 2017). The two species also have similar growth features, such as annual rings that can be used to age individuals, but L. ochroleuca is host to ~86x and 12x fewer epibiota on the stipe and holdfast (respectively) than L. hyperborea (Smale et al., 2015; Teagle & Smale, 2018). It is thought that the distribution of L. ochroleuca may be restricted to southern Europe because the optimal thermal range for sporophytes is between 12 and 22 °C (Franco et al., 2018). Gametophytes have an even narrower optimal thermal range for development, fecundity and germination between 15 and 18 °C (Izquierdo et al., 2002). However, predictions for species distributions indicate both L. ochroleuca and L. hyperborea will increase in abundance in northern habitats, coupled with subsequent retraction along their southern limits (Assis et al., 2018a; Assis et al., 2018b).

Kelp ecosystems are fluctuating in abundance and distribution, and undermanaged worldwide in terms of restoration and basic understanding of ecosystem function (Wernberg et al., 2019). The loss of these foundation species could lead to ecosystem collapse (Castorani et al., 2018) and changeover of dominance to alien primary producers, whether as biological invasions or ‘natural’ range expansions, can result in a significant reduction of alpha-diversity (Bernard-Verdier & Hulme, 2015), which has been shown in the epibiotic communities that certain members of European kelp forests can support (Smale et al., 2015; Teagle & Smale, 2018). Understanding the population dynamics and genetic variation of species is important for habitat monitoring and monitoring ecosystem function (Epstein & Smale, 2017; Krueger-Hadfield et al., 2017). Here, we report the first record of Laminaria ochroleuca in the Republic of Ireland, discovered during a citizen science marine habitat survey effort (inter- and subtidal) between National University of Ireland (NUI) Galway, Porcupine Marine Natural History Society (PMNHS), and Seasearch Ireland in Béal an Mhuirthead, Co. Mayo. We also report and compare the genetic diversity differentiation of the L. ochroleuca Scots Port population, the only known Irish population, to other sites in Europe (Assis et al. 2018b).

Methods

Surveys

Marine habitat surveys took place as a joint-effort between PMNHS and Seasearch Ireland during September 2018. SCUBA surveys in kelp habitats took place around the coastline of Béal an Mhuirthead from 0 to 11 m depth (Table 1), and species presence and abundance were noted using standard SeaSearch methodologies (SACFORN method; https://bd.eionet.europa.eu/). A small population of L. ochroleuca (~ 100 individuals counted) was discovered in a sheltered cove called Scots Port (Table 1) on the northwest facing coastline of Béal an Mhuirthead, September 10th, 2018. Divers returned to Scots Port on September 13th, 2018 and collected small portions of the L. ochroleuca blades near the apical meristem. Samples from 15 individuals were wiped clean of epiphytic diatoms and filamentous algae, preserved in silica gel, and shipped to the Krueger-Hadfield Lab at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) for genetic identification and diversity analyses.

DNA extraction

Approximately 12 mg of silica-dried tissue from each specimen was placed in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and were, then, ground with 2.8 mm ceramic beads using a bead mill (BeadMill24, Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Total genomic DNA was extracted using the Nucleospin® 96 Plant Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions except for the lysis step in which samples were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. DNA was eluted in 100 μL of molecular grade deionized water.

Genetic species identification

In order to genetically confirm specimens were Laminaria ochroleuca, we sequenced the mitochondrial intergenic spacer region between atp8 and t-RNA serine genes using the primers developed by Voisin et al. (2005). Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) amplification was performed on a total volume of 25 μL, containing 1 U of taq DNA polymerase, 2.5 mM of each dNTP, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 x reaction buffer, 250 nM of each primer and 5 μL of template DNA (diluted 1:100). The PCR program included 1 min at 95 °C, 32 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 50 °C, and 30 s at 72 °C, followed by a final elongation at 72 °C for 5 min. Approximately, 5 μL of PCR product using 1 μL of Orange G loading dye were visualized on 1.5% agarose gels stained with GelRed (Biotium, Fremont, CA, USA).

One μL of ExoSAP-It (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was added to 7 μL of PCR product and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C followed by 15 min at 80 °C. Four μL of 2 μM primer were added to each product and sequenced in the forward direction commercially by Eurofins Genomics (Louisville, KY, USA). Sequences were edited using 4Peaks (Nucleobytes, The Netherlands), aligned with the haplotypes listed in Table 1 from Rothman et al. (Rothman et al., 2017): DQ841612 (France), KY911984 (Portugal), and DQ841611 (Portugal) using Muscle (Edgar, 2004) in Seaview ver. 4.6 (Gouy et al., 2010) with default parameters.

Fragment analysis and allele calling

Twelve microsatellites previously developed for L. ochroleuca (LoIVVIV-23, LoIVVIV-26, LoIVVIV-17, LoIVVIV-7, Lo5–8, LoIVVIV-13, LoIVVIV-16, LoIVVIV-27, LoIVVIV-10, LoIVVIV-15, LoIVVIV-28, LoIVVIV-24; Coelho et al., 2014) were used to genotype 15 L. ochroleuca specimens. All microsatellite loci were amplified in simplex PCRs using either SimpliAmp or ProFlex thermocyclers (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). We used a 15 μL final volume containing 1X GoTaq® Flexi colorless reaction buffer (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 250 μM of each dNTP, 0.5 units of GoTaq® DNA polymerase (Promega Corp.) 150 nM labeled forward primer, 150 nM unlabeled forward primer, 250 nM unlabeled reverse primer, and 2 μL of template DNA (diluted to 1:100).

PCR products from each locus were combined into three poolplexes for fragment analysis: M1 (LoIVVIV-23 VIC, LoIVVIV-26 PET, LoIVVIV-17 NED, LoIVVIV-7 6-FAM), M2 (LoIVVIV-58 VIC, LoIVVIV-13 PET, LoIVVIV-16 NED, LoIVVIV-27 6-FAM), and M3 (LoIVVIV-10 VIC, LoIVVIV-15 PET, LoIVVIV-28 NED, LoIVVIV-24 6-FAM). One μL of each PCR product was added to a poolplex containing 10 μL of loading buffer including 9.7 μL of HiDi Formamide (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and 0.35 μL of size standard (GeneScan500 Liz; Applied Biosystems). Samples were electrophoresed on an ABI 3730xL genetic analyzer equipped with a 96-capillary array (Applied Biosystems). Alleles were scored manually using GENEIOUS PRIME 2019.0.3 (https://www.geneious.com). We attempted to re-PCR individuals missing genetic information at a locus at least twice. Allele sizes were binned with TANDEM software (Matschiner & Saltzburger, 2009). Microsatellite loci whose average rounding error was below 10% of the repeat size, as assessed by TANDEM (Matschiner & Saltzburger, 2009), are useful for subsequent analyses. In order to compare our data to that recently published by Assis et al. (2018a), we merged our allele calls by comparing the most frequent allele in the closest populations (located in Plymouth, United Kingdom, and sites in Brittany, France). Differences in allele sizes are constant through the range of a locus and differences between studies can be due to different PCRs or allele calling methods. After converting our alleles, the frequency of null alleles was estimated using ML-NullFreq (Kalinowski & Taper, 2006) with 1000 randomizations.

Genetic diversity and differentiation analyses

Using the 12 loci described above, we first evaluated gametic disequilibrium using the single multilocus estimate \( \overline{r_d} \) (Agapow & Burt, 2001) and implemented in the R package poppr ver. 2.0.2 (Kamvar et al., 2014). In order to test for departure from random associations between loci, the observed data set was compared to 1000 simulated datasets in which sex and recombination was imposed by randomly reshuffling the alleles among individuals for each locus (Agapow & Burt, 2001) followed by Bonferroni correction (Sokal & Rohlt, 1995). The two alleles of the same locus were shuffled together to maintain associations between alleles within loci in the randomized dataset. In addition to physical linkage on a chromosome, disequilibria may be due to a lack of recombination caused by selfing (mating system) or to differences in allele frequencies among populations (spatial genetic structure). Second, the average expected heterozygosity (HE) and observed heterozygosity (HO) were calculated using GenAlEx ver. 6.5 (Peakall & Smouse, 2006; Peakall & Smouse, 2012). Third, tests for Hardy-Weinberg proportions were performed using FSTAT, ver. 2.9.3.2 (Goudet, 1995). Fis was calculated for each locus and over all loci according to (Weir & Cockerham, 1984) and significance was tested by running 1000 permutations of alleles among individuals within samples.

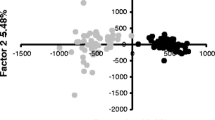

Next, we compared our data from Scots Port to the data set from Assis et al. (Assis et al., 2018a). We combined our data sets and used the following 10 loci in which we had both genotyped our specimens: LoIVVIV-23, LoIVVIV-26, LoIVVIV-17, LoIVVIV-7, LoIVVIV-16, LoIVVIV-27, LoIVVIV-10, LoIVVIV-15, LoIVVIV-28, LoIVVIV-24. We re-estimated the mean expected number of alleles (AE) and the private allelic richness (PE) on the smallest sample size of 11 sporophytes (i.e., 22 alleles) as previously analyzed by Assis et al. (2018a) using the program HP-Rare ver. 1.0 (Kalinowski, 2005). Finally, we calculated pairwise genetic differentiation for each pair of sites as Jost’s D in Genodive ver. 2.0b23 (Meirmans & Van Tienderen, 2004).

Results

Surveys and species identification

Scots Port has a mixed bottom, with bedrock and boulders on the north side of the cove where L. ochroleuca (Fig. 1a) and the kelp L. digitata were found, and a cobble bottom modified by waves throughout the mid- south part of the cove where the kelp Saccharina latissima and many mixed seaweeds were found. Laminaria ochroleuca is identified by its smooth, stiff stipe, golden broad blade, and relatively uncolonized claw-like holdfast (Fig. 1a; Bunker et al., 2017). Interestingly, L. ochroleuca was not found at other kelp forest sites along the coastline of Béal an Mhuirthead (Table 1) which are dominated by L. hyperborea (Fig. 1b), and include Alaria esculenta, Saccorhiza polyschides, S. latissima and L. digitata. Potential vectors for L. ochroleuca are few in the area, as Black Sod Pier is only open to small fishing vessels and recreational craft, but there is potential that the bay may offer refuge to larger vessels in bad weather conditions.

Kelp habitats in Béal an Mhuirthead where a) Laminaria ochroleuca is found in mixed seaweed communities at 2 m depth at Scots Port and b) Laminaria hyperborea dominates kelp forests between 2 and 10+ m depth at multiple sites including Muing Creana (pictured). Note the variation in epibionts on kelp stipes

All thalli sequenced with the atp8 mitochondrial marker belonged to the same haplotype (GenBank Acc. No. TBD) that matched the haplotype found in France and Portugal and reported in Rothman et al. (2017).

Genetic diversity and differentiation

All loci exhibited rounding errors below 10% of the repeat size (Additional file 1: Table S1). Only loci LoIVVIV-58 and LoIVVIV-13 showed evidence of null alleles (Additional file 1: Table S1). For LoIVVIV-58, the frequency was 0.05, whereas, for LoIVVIV-13, the frequency was 0.31. Therefore, we performed some of the subsequent analyses for Scots Port specifically on a dataset with and without LoIVVIV-13. Maximum likelihood estimators, such as ML-NullFreq, assume random mating in order to estimate null allele frequency (Kalinowski & Taper, 2006), but have been shown to be biased in other seaweeds in populations in which random mating does not occur (Krueger-Hadfield et al., 2013; Krueger-Hadfield et al., 2016). Thus, simply removing the locus may obscure important biological information (see, for example, Hansen & Taylor 2008).

The number of alleles per locus ranged from 1 to 4 (Additional file 1: Table S1), for a total of 34 alleles detected across the 15 individuals at 12 loci (Additional file 1: Table S2).

There was no evidence of gametic disequilibrium based on the multilocus estimate \( \overline{r_d} \) (including LoIVVIV-13: \( \overline{r_d} \) = 0.017, p-value > 0.3; excluding LoIVVIV-13: \( \overline{r_d} \) = 0.044, p-value > 0.1).

Expected heterozygosity varied from 0 to 0.696, with multilocus estimate of 0.427, and observed heterozygosity varied from 0 to 0.933, with a multilocus estimate of 0.562. Locus LoIVVIV-13 was the only locus with a positive Fis, though it was not significantly different from 0 (Table 2). The other loci were all generally negative and the overall Fis, value was significantly negative after Bonferroni correction when LoIVVIV-13 was removed, and when only 10 loci used by this study and by Assis et al. (2018a) were used.

The L. ochroleuca population at Scots Port exhibited allelic and private allelic richness, expected heterozygosity, and observed heterozygosity levels that were greater than nearby sites grouped in the Western English Channel by Assis et al. (2018a) (see Table 3 this study). Indeed, estimates were more similar to sites sampled in the southern Iberian Peninsula, the Azores, and north western Africa despite strong differentiation from these populations (Table 4). While the level of genetic differentiation was lower when compared to the sites in the Western English Channel, the average differentiation was 0.331, suggesting strong variation between this Irish site and sites in England and France (Table 4).

Discussion

We confirm the presence of Laminaria ochroleuca in the Republic of Ireland. Scots Port is located ~ 1040 km away from the nearest population of L. ochroleuca in the UK and ~ 1630 km away from the nearest population in France. The knowledge of Irish kelp forest ecosystem is woefully inadequate, including simple natural history information, such as species distributions. Thus, the presence of L. ochroleuca, which is known to harbor much less biodiversity than L. hyperborea, its congeneric and current dominant species in Boreal kelp forests, necessitates further studies beginning with obtaining distributional data.

Assis et al. (2018a) suggested that the dispersal capability of L. ochroleuca can be as far as thousands of kilometres, but fewer than 5% of dispersal events would extend beyond 3.63 km. All estimates are greater than dispersal distances of conspecific L. hyperborea, which is estimated to be 300 m for zoospores (Fredriksen et al., 1995). Thus, greater predicted dispersal distances in L. ochroleuca may explain its arrival, via rafting or another mechanism, in this remote cove in Co. Mayo. Alternatively, L. ochroleuca may be far more widespread than originally thought, extending in linear series along Ireland’s coastline. Other kelps, such as L. digitata and L. hyperborea, exhibit strong patterns of isolation by distance (e.g., Robuchon et al. 2014). If there are more L. ochroleuca populations in Ireland, we may expect a similar pattern to the stepping-stone connectivity suggested by Assis et al. (2018a), in which case we would expect strong differentiation between English and French sites with Scots Port. In addition to genetic patterns, tolerance to the average winter temperature (8 ± 1 °C; www.met.ie) and low irradiance in this area of Ireland is not expected for L. ochroleuca and suggests physiological plasticity in this species that warrants further investigation.

We found allelic diversity and expected heterozygosity to be more like populations in the Iberian Peninsula than France and the UK (Table 3) when adjusting for the same sample size and the same set of markers from a previous study of L. ochroleuca (Assis et al., 2018a). While this Irish population appears to be reproducing sexually, the overall Fis value was negative, indicating heterozygote excess. The breeding population at Scots Port could be small, in which only a few individuals contribute to the next generation such that there are allele frequency differences between female and male gametophytes by chance alone (Rassmussen, 1979). In small, sexual populations, if individuals cannot undergo selfing, then the chances of producing homozygous offspring are less (Balloux, 2004). Though L. ochroleuca could, in theory, undergo intergametophytic selfing (Klekowski, 1969), in which gametophytes mate that share the same diploid sporophytic parent, there is no evidence of which we are aware to suggest this type of mating system as FIS values were zero or generally negative (Table 2; see Assis et al. 2018a). We only genotyped adult sporophytes and would need to genotype young sporophytes to determine if there were departures from Hardy-Weinberg in germlings as well (Stoeckel et al., 2006). Alternatively, some species may be more prone to heterosis (Hansson & Westerberg, 2002) in which the most homozygous individuals are lost over time. To determine whether this might be true in the Scots Port population of L. ochroleuca, we would also need to genotype young sporophytes to determine if there is a general trend of increasing heterozygosity in older sporophytes. This is especially interesting because site conditions are outside the thermal niche of L. ochroleuca (Franco et al., 2018; Izquierdo et al., 2002), potentially exerting a selective pressure on genotypes. A third explanation could be negative assortative mating in which individuals avoid mating with close relatives (Hartl & Clark, 1999). Alternatively, fourth, if long distance dispersal is possible (see discussion in Assis et al. (2018a), there may have been multiple sources of the Scots Port population, generating an excess of heterozygotes through admixture (reviewed in Rius and Darling, 2014). Future studies or surveys of the Irish coastline should include collection and genotyping of L. ochroleuca gametophytes and sporophytes to tease these hypotheses apart.

The present range expansion of L. ochroleuca highlights a critical need to monitor Irish kelp forests. Citizen science organizations like Seasearch Ireland can be an excellent way to involve local communities that have a vested interest in the health of these ecosystems, but resources should be made available for long term ecological research (LTER) as well. The lack of any subtidal LTER in Ireland and the UK until recently (Smale et al., 2013) prevents us from monitoring ecosystem shifts driven by climate changes, species range expansions, and other man-made disturbances including wild-harvest. This new record of L. ochroleuca in Ireland is a sign that subtidal kelp forests are changing in Ireland and there will be associated impacts to ecosystems services that are not thoroughly understood.

Conclusion

This is the first record of an L. ochroleuca population in the Republic of Ireland. It’s remote location indicates there are likely more populations along the coastline, however the allelic richness and heterozygosity reflect that of Iberian populations within it’s distribution center. Future investigations of dispersal vectors and population connectivity are warranted and this discovery highlights the importance of citizen science and need for monitoring systems in the changing marine environment.

Abbreviations

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- dNTP:

-

Nucleoside triphosphate

- LTER:

-

Long term ecological research

- NUI Galway:

-

National University of Ireland Galway

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PMNHS:

-

Porcupine Marine Natural History Society

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- SCUBA:

-

self contained underwater breathing apparatus

- UAB:

-

University of Alabama at Birmingham

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

Agapow PM, Burt A. Indices of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Mol Ecol Notes. 2001;1:1–2.

Araújo RM, Assis J, Aguillar R, et al. Status, trends and drivers of kelp forests in Europe: an expert assessment. Biodivers Conserv. 2016;25:1319–48.

Assis J, Araújo MB, Serrão EA. Projected climate changes threaten ancient refugia of kelp forests in the North Atlantic. Glob Chang Biol. 2018b;24:e55–66.

Assis J, Serrão EÁ, Coelho NC, Tempera F, Valero M, Alberto F. Past climate changes and strong oceanographic barriers structured low-latitude genetic relics for the golden kelp Laminaria ochroleuca. J Biogeogr. 2018a;45:2326–36.

Balloux F. Heterozygote excess in small populations and the heterozygote-excess effective population size. Evolution (N Y). 2004;58:1891–900.

Bernard-Verdier M, Hulme PE. Alien plants can be associated with a decrease in local and regional native richness even when at low abundance. J Ecol. 2015;103:143–52.

Bunker FD, Brodie JA, Maggs CA, Bunker AR. Seaweeds of Britain and Ireland. Second Ed. Plymouth: Wild Nature Press; 2017.

Castorani MCN, Miller RJ, Barbara S (2018) Structuring kelp forest communities Loss of foundation species : disturbance frequency outweighs severity in structuring kelp forest communities. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2485.

Coelho NC, Serrao EA, Alberto F. Characterization of fifteen microsatellite markerrs for the kelp Laminaria ochroleuca and cross species amplification within the genus. Microsatellite Lett. 2014;6:949–50.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high thoughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7.

Epstein G, Smale DA. Undaria pinnatifida: a case study to highlight challenges in marine invasion ecology and management. Ecol Evol. 2017;7:8624–42.

Franco JN, Tuya F, Bertocci I, Rodríguez L, Martínez B, Sousa-Pinto I, Arenas F. The ‘golden kelp’ Laminaria ochroleuca under global change: integrating multiple eco-physiological responses with species distribution models. J Ecol. 2018;106:47–58.

Fredriksen S, Sjøtun K, Lein TE, Rueness J. Spore dispersal in Laminaria hyperborea (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae). Sarsia. 1995;80:47–54.

Gayral P (1958) Algues de la Cote Atlantique Marocaine. Rabat.

Goudet J. Computer note. SPAM (version 3.2): statistics program for analyzing mixtures. J Hered. 1995;86:485–6.

Gouy M, Guindon S, Gascuel O. SeaView version 4: a multiplatform graphical user interface for sequence alignment and phylogenetic tree building. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:221–4.

Hansen BD, Taylor AC. Isolated remnant or recent introduction? Estimating provenance of Yellingbo Leadbeater’s possums by genetic analysis and bottleneck simulation. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:4039–59.

Hansson B, Westerberg L. On the correlation between heterozygosity and fitness in natural populations. Mol Ecol. 2002;11:2467–74.

Hartl D, Clark A. Principles of population genetics, 1997. Sunderland. MA Sinauer. 1999;54:1042.

Izquierdo JL, Pérez-Ruzafa IM, Gallardo T. Effect of temperature and photon fluence rate on gametophytes and young sporophytes of Laminaria ochroleuca Pylaie. Helgol Mar Res. 2002;55:285–92.

John DM. An ecological study on Laminaria ochroleuca. J Mar Biol Assoc United Kingdom. 1969;49:175–87.

Kalinowski ST. HP-Rare1.0: a computer program for performing rarefaction on measures of allelic richness. Mol Ecol Notes. 2005;5:187–9.

Kalinowski ST, Taper ML. Maximum likelihood estimation of the frequency of null alleles at microsatellite loci. Conserv Genet. 2006;7:991–5.

Kamvar ZN, Tabima J, Grünwald NJ. Poppr: an R package for genetic analysis of populations with clonal, partial clonality, and/or sexual reproduction. PeerJ. 2014;2:e281.

Klekowski EJ. Reproductive biology of the Pteridophyta. II. Theoretical considerations. Bot J Linn Soc. 1969;62:347–59.

Krueger-Hadfield SA, Kollars NM, Byers JE, Greig TW, Hamman M, Murray D, Murren CJ, Strand AE, Terada R, Weinberger F, Sotka EE. Invasion of novel habitats uncouples haplo-diplontic life cycles. Mol Ecol. 2016;25:3801–16.

Krueger-Hadfield SA, Kollars NM, Strand AE, et al. Genetic identification of source and likely vector of a widespread marine invader. Ecol Evol. 2017;7:4432–47.

Krueger-Hadfield SA, Roze D, Mauger S, Valero M. Intergametophytic selfing and microgeographic genetic structure shape populations of the intertidal red seaweed Chondrus crispus. Mol Ecol. 2013;22:3242–60.

Matschiner M, Saltzburger W. TANDEM: integrating automated allele binning into genetics and genomics workflows. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1982–3.

Meirmans PG, Van Tienderen PH. GENOTYPE and GENODIVE: two programs for the analysis of genetic diversity of asexual organisms. Mol Ecol Notes. 2004;4:792–4.

Parke. Laminaria ochroleuca De la Pylaie growing on the coast of Britain. Nature. 1948;1:92–101.

Peakall R, Smouse PE. Genalex 6: genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006;6:299–5.

Peakall R, Smouse PE. GelAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research--an update. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2537–9.

Picton BE, Morrow CC. BioMar Survey of marine species and habitats of Ireland. Ireland: Belfast, N; 2006.

Rassmussen DI. Sibling clusters and genotypic frequencies. Am Nat. 1979;113:948–51.

Rius M, Darling JA. How important is intraspecific genetic admixture to the success of colonising populations? Trends Ecol Evol. 2014;29:233–42.

Robuchon M, Le Gall L, Mauger S, Valero M. Contrasting genetic diversity patterns in two sister kelp species co-distributed along the coast of Brittany, France. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:2669–85.

Rothman MD, Mattio L, Anderson RJ, Bolton JJ. A phylogeographic investigation of the kelp genus Laminaria (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae), with emphasis on the South Atlantic Ocean. J Phycol. 2017;53:778–89.

Simkanin C, Power AM, Myers A, McGrath D, Southward A, Mieszkowska N, Leaper R, O’Riordan R. Using historical data to detect temporal changes in the abundances of intertidal species on Irish shores. J Mar Biol Assoc United Kingdom. 2005;85:1329–40.

Smale DA, Burrows MT, Moore P, O’Connor N, Hawkins SJ. Threats and knowledge gaps for ecosystem services provided by kelp forests: a Northeast Atlantic perspective. Ecol Evol. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.774.

Smale DA, Wernberg T, Yunnie ALE, Vance T. The rise of Laminaria ochroleuca in the Western English Channel (UK) and comparisons with its competitor and assemblage dominant Laminaria hyperborea. Mar Ecol. 2015;36:1033–44.

Sokal RR, Rohlt H. Biometry. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1995.

Stoeckel S, Grange J, Fernández-Manjarres JF, Bilger I, Frascaria-Lacoste N, Mariette S. Heterozygote excess in a self-incompatible and partially clonal forest tree species - Prunus avium. L. Mol Ecol. 2006;15:2109–18.

Teagle H, Smale DA. Climate-driven substitution of habitat-forming species leads to reduced biodiversity within a temperate marine community. Divers Distrib. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12775.

Voisin M, Engel CR, Viard F. Differential shuffling of native genetic diversity across introduced regions in a brown alga: Aquaculture vs. maritime traffic effects. PNAS. 2005;102:5432–7.

Weir BS, Cockerham CC. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution. 1984;38:1358–70.

Wernberg T, Krumhansl K, Filbee-Dexter K, Pedersen MF. Status and trends for the world’s kelp forests. In: World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation. Ed 2: Academic Press; 2019. p. 57–78.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank members of the PMNHS and both Sea search Ireland and UK participants, especially Linn Baldock, Julia Nunn, and Dr. John Breen. We also thank Filipe Alberto who provided advice on how to combine the Assis et al. (2018) data with our own.

Funding

KMS was funded by the Irish Research Council Government Postdoctoral Fellowship [GOPID/2016/545] and SAKH was funded by start-up funds from the University of Alabama at Birmingham. These funding bodies had no role in design of the collections or analysis of the data. Seasearch Ireland is supported in part by the Irish Underwater Council, Comhairle Fo-Thuinn.

Availability of data and materials

Mitochondrial sequences are provided with Genbank Acc. TBD. Microsatellite genotypes are provided in Additional file 1: Table S2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KMS participated in PMNHS and Seasearch surveys, collected the kelp samples, and wrote the manuscript. TO and RO participated and ran PMNHS and Seasearch surveys and edited the manuscript. SAKH did the laboratory work, processed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. The number of alleles, allele range, null allele frequency, and TANDEM ver. 1.09 output (Matschiner & Saltzburger 2009), including the specified repeat size, rounding method, average rounding error and error threshold for each microsatellite locus used to genotype L. hyperborea populations. The only locus with a higher rounding error than 10% of the repeat size was locus Gver_6311, shown in red and bold. All individuals flagged as errors were manually checked to make sure they were manually binned (Krueger-Hadfield et al. 2013). Table S2. Microsatellite genotypes of 15 Laminaria ochroleuca sporophytes from Béal an Mhuirthead. Lo is the same as LoIVVIV. (DOCX 36 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Schoenrock, K.M., O’Callaghan, T., O’Callaghan, R. et al. First record of Laminaria ochroleuca Bachelot de la Pylaie in Ireland in Béal an Mhuirthead, county Mayo. Mar Biodivers Rec 12, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-019-0168-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-019-0168-3