Abstract

Human infection caused by non-human primate malarial parasites, such as Plasmodium knowlesi and Plasmodium cynomolgi, occurs naturally in Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam. Members of the Anopheles dirus species complex are known to be important vectors of human malarial parasites in the forested areas of southern and central Vietnam, including those in Khanh Phu commune and Khanh Hoa Province. Recent molecular epidemiological studies in Vietnam have reported cases of co-infection with Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, and P. knowlesi in An. dirus. The commonly found macaques in the forest in the forested areas are suspected to be bitten by the same An. dirus population that bites humans. A recent epidemiological study identified six species of malarial parasites in sporozoite-infected An. dirus using polymerase chain reaction, of which P. vivax was the most common, followed by P. knowlesi, Plasmodium inui, P. cynomolgi, Plasmodium coatneyi, and P. falciparum. Based on a gametocyte analysis, the same allelic gametocyte types were observed in both humans and mosquitoes at similar frequencies. These observations suggest that people who stay overnight in the forests are frequently infected with both human and non-human primate malarial parasites, leading to the emergence of novel zoonotic malaria. Moreover, it is suggested that mosquito vector populations should be controlled and monitored closely.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria is among the most important infectious diseases caused by protozoans in humans. It is transmitted in tropical and subtropical areas. In 2015, about 212 million cases and 429,000 deaths related to Malaria were reported [1]. “Forest malaria” is a term frequently used to describe a malarial characteristic that is mainly found in Southeast Asia. Malarial parasite transmission occurs in the forested areas of the southern and central provinces of Vietnam [2, 3] and throughout other Southeast Asian countries. Malaria has become a public health concern in these areas.

Five species of malarial parasites, including Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale wallikeri, and Plasmodium ovale curtisi, infect humans. On the other hand, 13 species of malarial parasites that infect non-human primates are found in Southeast Asian countries [4]. Among these non-human malarial parasites, Plasmodium knowlesi is now well known to infect humans and is considered a threat to human health in several Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam [2, 5,6,7,8]. Recently, the first naturally acquired human Plasmodium cynomolgi infection was reported in the Malaysian peninsula [9]. Other malarial parasites that infect non-human primates, including Plasmodium inui, Plasmodium eyesi, and Plasmodium schwetzi, can infect humans through experimental or accidental infection [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. These findings indicate that malarial parasites have the ability to switch hosts [19]. Malarial parasites that infect non-human primates can only cause zoonotic infection when mosquito vectors infected with these parasites encounter people. However, the process of zoonotic transmission is not sufficiently understood. Thus, malarial parasites in mosquitoes should be identified and characterized to fully understand the complexities of malarial parasite transmission.

The results of the epidemiological studies on malaria conducted in the Khanh Phu commune, Khanh Vinh, and Khanh Hoa Province, Vietnam, were used in this review. Khanh Phu is a commune with about 3000 residents, mainly of the Raglai ethnic minority. Most of the residents live between the forested foothills on the east side of the Truong Son mountain range in south-central Vietnam. Malaria in these areas was previously hyper- to holo-endemic.

Anopheline species as a malaria vector

The characteristics of mosquito species can affect the transmission of malarial parasites between humans and non-human primates. Of about the 430 Anopheles species, only 25–30 are vectors of human and non-human primate malarial parasites [20, 21]. In the Greater Mekong Subregion, most often reported vectors were Anopheles minimus, Anopheles dirus, Anopheles sundaicus, Anopheles sinensis, and Anopheles maculatus [22]. In south and central Vietnam, the same Anopheles species that are considered as malaria vectors are collected [2, 3, 20, 22, 23]. However, the main vector in these areas is now An. dirus instead of An. minimus, An. maculatus, and other vectors [2, 3, 20].

Biting rhythm of the Anopheles mosquito

In Khanh Phu commune, An. dirus mosquitoes were collected every month with an average human-biting density of 3.5 per person per night (Table 1) [20, 24, 25]. As shown in Fig. 1, An. dirus started to bite humans immediately after sunset, which peaks at 20:00–22:00 and then 0:00–2:00 [20]. A similar biting rhythm of An. dirus was found in the previous report in Vietnam. However, a late biting activity of An. dirus was observed in Thailand and Lao PDR [22, 26,27,28,29]. In relation to biting activity and environmental factors, biting density in the forest is higher than that in the village [26]. This biting density did not differ between forest fringe and forest [20]. The early biting activity of An. dirus is dependent on species, location, and other factors. Previously, nocturnal rainfall did not affect the biting activity of this species in the Khanh Phu commune, and no difference in the biting activity was observed between rainy and dry nights [22]. The biting activity rate was increased in moonlight nights than moonless nights [22] and in the outdoors than the indoors [26, 30]. In areas including the Khanh Hoa Province and Ninh Thuan Province, residents often sleep outdoors in hammocks or plot huts in the forests. This activity causes humans to be more susceptible to mosquito bites. These findings suggest that the transmission of malarial parasites occurs because of a dependent pattern of behavior between humans and mosquitoes.

Prevalence of malaria infection in mosquito species

Recent molecular epidemiological studies in Vietnam reported the co-infection of P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi in An. dirus [2, 31]. The commonly found macaques in the forests of the study area are suspected to be bitten by the same An. dirus population that bites humans. To resolve the problem, a total of 120 female An. dirus mosquitoes infected with sporozoites, collected at the forest and forest fringe in the Khanh Phu commune, were analyzed for the detection of malarial parasite species using nested PCR (Table 2). Based on the analysis, six species of malarial parasites were detected, of which P. vivax is the most common and followed by P. knowlesi, P. falciparum, P. inui, P. cynomolgi, and Plasmodium coatneyi. However, P. malariae and Plasmodium ovale were not detected among the analyzed mosquito samples (Table 2).

Those sporozoite-positive An. dirus showed single and mixed species parasite infection. Among the vectors that cause single species infection, P. vivax was dominant, followed by P. falciparum, P. coatneyi, P. cynomolgi, P. inui, and P. knowlesi (Table 2). On the other hand, the co-infections of malarial parasite species were common, with 38% of mosquitoes infected by two or more species of the malarial parasites, with most cases considered as mixed species infection caused by P. vivax and another species (Table 2). As shown in Table 2, P. vivax co-infections with non-human primate malaria species, such as P. knowlesi, P. inui, P. cynomolgi, and P. coatneyi, were observed. For P. falciparum, co-infection with non-human primate Plasmodium species was observed only in P. inui. In contrast, co-infection among human Plasmodium species, such as P. vivax and P. falciparum (including six cases of co-infection with P. vivax and P. knowlesi), was observed. Similar molecular epidemiological studies using mosquitoes as a target are not available. However, Lee et al. [32] reported that nested PCR analysis of blood samples of wild macaques, which were collected in the Kapit Division of Sarawak, Malaysia, detected five non-human primate malarial parasites, including P. inui, P. knowlesi, P. coatneyi, P. cynomolgi, and the Plasmodium fieldi. Among them, single and mixed species infections were observed. These findings from mosquitoes and macaques indicated that transmission of malarial parasites in mosquitoes is dependent on the monkey reservoir and/or was maintained between humans. Therefore, further study should be conducted to obtain detailed information about the transmission of malarial parasites.

The data show that An. dirus is infected with two species of human malarial parasites (P. falciparum and P. vivax) and four species of non-human primate malarial parasites (P. knowlesi, P. inui, P. cynomolgi, and P. coatneyi) (Table 2). These results suggest that both humans and macaques are bitten by An. dirus in the forests. To obtain data and verify whether and which macaques are the reservoirs of non-human primate malarial parasites, macaque fecal samples that were collected from forest floors and a cage in the forest where An. dirus is commonly found were analyzed. Among these macaques, the caged macaques were infected with P. cynomolgi, P. coatneyi, P. inui, and P. knowlesi, of which the latter species is only found in fecal samples [33]. As shown in Table 2, approximately one-third of An. dirus were infected by two or more species of malarial parasites, and these were often a combination of human and non-human primate parasites. The numerous co-infections and the lack of differences between the collection sites and biting times further suggest that all these parasites are transmitted by only one population of An. dirus, which bites humans as readily as they bite macaques.

The emergence of novel zoonotic malarial infections

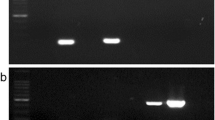

P. knowlesi is considered as the “fifth human malarial parasite,” which is somehow controversial. The controversy stems from the fact that whether this parasite can be transmitted from human to human is not known. If human infection only resulted from a “spill-over” of transmission between monkeys, then the infection must be considered a zoonotic disease rather than a human one. First, to determine whether P. knowlesi is also infectious to mosquitoes, its capability of producing gametocytes should be investigated. Previous studies have reported the presence of P. knowlesi gametocytes, identified by microscopy, in the blood of infected patients [5, 34,35,36]. Recently, transcripts of pks25, the P. knowlesi orthologue of Pvs25 [37], in dried blood samples of people infected with P. knowlesi in the Khanh Phu commune was detected, although those samples did not show either gametocytes or the asexual forms of P. knowlesi through a microscopy [25]. This finding indicates that P. knowlesi, which infects humans in the Khanh Phu commune, may also be infectious to mosquitoes.

Both the behavior of humans and recent findings on transmission indicate that humans who stay overnight in forests are frequently infected with a range of similar malarial parasites, several of which have been shown to cause diseases in humans [2, 5,6,7,8,9,10, 13, 16, 17, 38]. The implications of this are potentially serious. Given that malarial parasites are capable of infecting different species and causing zoonotic infections under certain circumstances, exposure is the major factor that causes new zoonotic infection. Humans who are routinely and regularly exposed to inoculations of (currently) non-human primate sporozoites are at high risk for novel zoonotic malarial infections.

Conclusion

Recent studies in the Khanh Phu commune indicated that both human and non-human primate malarial parasite sporozoites from the same mosquito population were considered as a characteristic of malaria, and a similar frequency of the same allelic types of gametocytes was also observed in humans and mosquitoes captured in the forest area. These findings suggest that humans who stay overnight in the forests are frequently infected with both human and non-human primate malarial parasites, thus causing the emergence of novel zoonotic malaria. Moreover, these findings suggest that mosquito vector populations should be controlled and monitored closely.

References

WHO. World malaria report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

Marchand RP, Culleton R, Maeno Y, Quang NT, Nakazawa S. Co-infections of Plasmodium knowlesi, P. Falciparum, and P. Vivax among humans and Anopheles dirus mosquitoes, southern Vietnam. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1232–9. doi: 10.3201/eid1707.101551.

Grietens KP, Xuan XN, Ribera J, Duc TN, Bortel WV, Ba NT, Van KP, Xuan HL, D'Alessandro U, Erhart A. Social determinants of long lasting insecticidal hammock use among the Ra-glai ethnic minority in Vietnam: implications for forest malaria control. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29991. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029991.

Collins WE. Major animal models in malaria research: simian. In: Wernsdofer WH and McGregor S ediors. Malaria: principles and practice of Malariology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. P. 1473-1501.

Singh B, Kim Sung L, Matusop A, Radhakrishnan A, Shamsul SS, Cox-Singh J, Thomas A, Conway DJ. A large focus of naturally acquired Plasmodium knowlesi infections in human beings. Lancet. 2004;363:1017–24.

Putaporntip C, Hongsrimuang T, Seethamchai S, Kobasa T, Limkittikul K, Cui L, Jongwutiwes S. Differential prevalence of Plasmodium infections and cryptic Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans in Thailand. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1143–50. doi: 10.1086/597414.

Luchavez J, Espino F, Curameng P, Espina R, Bell D, Chiodini P, Nolder D, Sutherland C, Lee KS, Singh B. Human infections with Plasmodium knowlesi, the Philippines. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:811–3. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.071407.

Jiang N, Chang Q, Sun X, Lu H, Yin J, Zhang Z, Wahlgren M, Chen Q. Co-infections with Plasmodium knowlesi and other malaria parasites, Myanmar. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1476–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1609.100339.

Ta TH, Hisam S, Lanza M, Jiram AI, Ismail N, Rubio JM. First case of a naturally acquired human infection with Plasmodium cynomolgi. Malar J. 2014 Feb 24;13:68. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-68.

Schmidt LH, Greenland R, Genther CS. The transmission of Plasmodium cynomolgi to man. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1961;10:679–88.

Deane LM, Deane MP, Ferreira NJ. Studies on transmission of simian malaria and on a natural infection of man with Plasmodium simium in Brazil. Bull World Health Organ. 1966;35:805–8.

Coatney GR, Chin W, Contacos PG, King HK. Plasmodium inui, a quartan-type malaria parasite of old world monkeys transmissible to man. J Parasitol. 1966;52:660–3.

Coatney GR, Colins WE, Warren M, Contacos PG. The primate malaria. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Print. Office; 1971. p. 43–339. Stock No. 1744-0005

Chin W, Contacos PG, Collins WE, Jeter MH, Alpert E. Experimental mosquito transmission of Plasmodium knowlesi to man and monkey. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1968;17:355–8.

Contacos PG, Coatney GR, Orihel TC, Collins WE, Chin W, Jeter MH. Transmission of Plasmodium schwetzi from the chimpanzee to man by mosquito bite. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1970;19:190–5.

Cross JH, Hsu-Kuo MY, Lien JC. Accidental human infection with Plasmodium cynomolgi bastianellii. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1973;4:481–3.

Most H. Plasmodium cynomolgi malaria: accidental human infection. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973;22:157–8.

Baird JK. Malaria zoonoses. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:269–77.

Hayakawa T, Arisue N, Udono T, Hirai H, Sattabongkot J, Toyama T, Tsuboi T, Horii T, Tanabe K. Identification of Plasmodium malariae, a human malaria parasite, in imported chimpanzees. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007412.

Maeno Y, Quang NT, Culleton R, Kawai S, Masuda G, Nakazawa S, Marchand RP. Humans frequently exposed to a range of non-human primate malaria parasite species through the bites of Anopheles Dirus mosquitoes in south-central Vietnam. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:376. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0995-y.

White GB. Malaria vector ecology and genetics. Br Med Bull. 1982;38(2):207–12.

Hii J, Rueda LM. Malaria vectors in the greater Mekong subregion: overview of malaria vectors and remaining challenges. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2013;44(Suppl 1):73–165.

Trung HD, Bortel WV, Sochantha T, Keokenchanh K, Briët OJ, Coosemans M. Behavioural heterogeneity of Anopheles species in ecologically different localities in Southeast Asia: a challenge for vector control. Tropical Med Int Health. 2005;10(3):251–62.

Maeno Y, Culleton R, Quang NT, Kawai S, Marchand RP, Nakazawa S. Plasmodium knowlesi and human malaria parasites in Khan Phu, Vietnam: gametocyte production in humans and frequent co-infection of mosquitoes. Parasitology. 2017;144(4):527–35. doi: 10.1017/S0031182016002110.

Maeno Y, Quang NT, Culleton R, Kawai S, Masuda G, Hori K, Nakazawa S, Marchand RP. Detection of the Plasmodium falciparum Kelch-13 gene P553L mutation in sporozoites isolated from mosquito salivary glands in South-Central Vietnam. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10(1):308. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2247-9.

Van Bortel W, Trung HD, Hoi le X, Van Ham N, Van Chut N, Luu ND, Roelants P, Denis L, Speybroeck N, D’Alessandro U, Coosemans M. Malaria transmission and vector behaviour in a forested malaria focus in central Vietnam and the implications for vector control. Malar J. 2010 Dec 23;9:373. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-373.

Baimai V, Kijchalao U, Sawadwongporn P, Green CA. Geographic distribution and biting behaviour of four species of the Anopheles dirus complex (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1988;19(1):151–61.

Tananchai C, Tisgratog R, Juntarajumnong W, Grieco JP, Manguin S, Prabaripai A, Chareonviriyaphap T. Species diversity and biting activity of Anopheles dirus and Anopheles baimaii (Diptera: Culicidae) in a malaria prone area of western Thailand. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:211. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-211.

Vythilingam I, Phetsouvanh R, Keokenchanh K, Yengmala V, Vanisaveth V, Phompida S, Hakim SL. The prevalence of Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae) mosquitoes in Sekong Province, Lao PDR in relation to malaria transmission. Tropical Med Int Health. 2003;8(6):525–35.

Tananchai C, Tisgratog R, Juntarajumnong W, Grieco JP, Manguin S, Prabaripai A, Chareonviriyaphap T. Species diversity and biting activity of Anopheles dirus and Anopheles baimaii (Diptera: Culicidae) in a malaria prone area of western Thailand. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:211. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-211

Nakazawa S, Marchand RP, Quang NT, Culleton R, Manh ND, Maeno Y. Anopheles dirus co-infection with human and monkey malaria parasites in Vietnam. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:1533–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.08.005.

Lee KS, Divis PC, Zakaria SK, Matusop A, Julin RA, Conway DJ, Cox-Singh J, Singh B. Plasmodium knowlesi: reservoir hosts and tracking the emergence in humans and macaques. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(4):e1002015. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002015.

Abkallo HM, Liu W, Hokama S, Ferreira PE, Nakazawa S, Maeno Y, Quang NT, Kobayashi N, Kaneko O, Huffman MA, Kawai S, Marchand RP, Carter R, Hahn BH, Culleton R. DNA from pre-erythrocytic stage malaria parasites is detectable by PCR in the faeces and blood of hosts. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44(7):467–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.03.002.

Lee KS, Cox-Singh J, Singh B. Morphological features and differential counts of Plasmodium knowlesi parasites in naturally acquired human infections. Malar J. 2009;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-73.

Tang TH, Salas A, Ali-Tammam M, del Carmen Martínez M, Lanza M, Arroyo E, Rubio JM. First case of detection of Plasmodium knowlesi in Spain by Real Time PCR in a traveller from Southeast Asia. Malar J. 2010;9:219. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-219.

Cox-Singh J, Singh B. Knowlesi malaria: newly emergent and of public health importance? Trends Parasitol. 2008 Sep;24(9):406–10. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.06.001.

Grigg MJ, William T, Menon J, Dhanaraj P, Barber BE, Wilkes CS, von Seidlein L, Rajahram GS, Pasay C, McCarthy JS, Price RN, Anstey NM, Yeo TW. Artesunate-mefloquine versus chloroquine for treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in Malaysia (ACT KNOW): an open-label, randomized controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(2):180–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00415-6.

Garnham PCC, Molinari V, Shute PG. Differential diagnosis of bastianellii and vivax malaria. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;27:199–202.

Acknowledgments

This review is dedicated to the memory of the late professor Masamichi Aikawa.

I thank Nguyen Tuyen Quang, Richard Culleton, Satoru Kawai, Gaku Masuda, Kaoru Hori, Shusuke Nakazawa, and Ron P. Marchand for their collaboration. I also thank the Khanh Phu Malaria Research Unit, Provincial Health Service, and Malaria Control Centre of Khanh Hoa Province as well as the authorities of Khanh Vinh district and Khanh Phu municipality for their administrative support.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the following two grants: (i) JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 26360029 and 17H04513 and (ii) the Cooperative Research Grants from Joint Usage/Research Center on Tropical Disease, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University (2015-Ippan-14, 2016-Ippan-9).

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was certified as permitted standard procedures by the National Institute of Malariology, Parasitology and Entomology in Hanoi, and was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees of Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University (permit number: 10121662-5). All adult volunteers including mosquito collectors provided informed consent and for children, consent was obtained from close relatives.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Maeno, Y. Molecular epidemiology of mosquitoes for the transmission of forest malaria in south-central Vietnam. Trop Med Health 45, 27 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-017-0065-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-017-0065-6