Abstract

Background

Traditional vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, cigarette smoking, and cardiovascular disease with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation have been linked to cognitive impairment in patients with chronic kidney disease. Therefore, interventions for cognitive function that can be performed during hemodialysis are needed. In this regard, n-back training has been demonstrated to be effective in patients with cognitive impairment.

Methods

In this pre-post study, 12 patients underwent n-back training during hemodialysis. The patients, aged 52–80 years, had mild cognitive impairment and were tested before and after a 3-month training period. This study was carried out in a single dialysis center. The Mini-Mental State Examination, Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Japanese version, Benton Visual Retention Test, Trail Making Test, visual cancelation task, Symbol Digit Modality Test, and Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task were used as outcome measures.

Results

All patients completed the 3-month training program. Improvements were seen in scores for the Mini-Mental State Examination (P = 0.01), Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Japanese version (P = 0.01), Benton Visual Retention Test (P = 0.02), Trail Making Test-B (P = 0.01), and Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task 1 s (P = 0.01) and 2 s (P = 0.01) from baseline to 3 months.

Conclusions

Cognitive training during hemodialysis improved cognitive and attention function in patients with mild cognitive impairment. This suggests that the simultaneous provision of n-back training and hemodialysis can be effective for treating chronic kidney disease with cognitive impairment.

Trial registration

UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000033742); retrospectively registered on August 13, 2018.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, over 850 million people have kidney diseases, of whom approximately 3.5 million were undergoing regular dialysis as of 2019 [1]. Additionally, traditional vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, cigarette smoking, and cardiovascular disease with myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation have been linked to cognitive impairment in patients with chronic kidney disease [2]. Cognitive impairment is often a further clinical issue for these patients, as demonstrated by a study that found severe impairment in 37.3% of patients undergoing hemodialysis; overall, 87.3% had some degree of impairment (severe, moderate, or mild) and only 12.7% showed normal cognition [3]. As a prognostic factor, cognitive impairment often correlates to poor outcomes [4, 5], suggesting that an intervention addressing cognitive decline may improve outcomes for hemodialysis patients.

Recently, n-back training was reported to improve performance on tasks related to prefrontal functioning and attention function [6,7,8]. Furthermore, interventions using cognitive tasks [9] and exercise [10, 11] have been utilized as non-pharmacological therapies for cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older adults.

Given the prognostic value of cognitive function as it relates to renal failure and the effectiveness of cognitive training with older adults, we aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of providing simultaneous n-back training (memory function, attention function) to patients receiving hemodialysis treatments. If this intervention can be successfully employed alongside dialysis, it may be useful for improving overall health outcomes for hemodialysis patients.

Methods

Study design and participants

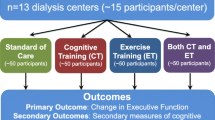

In this study, which employed a pre-post design, every participant individually received 3 months’ training between August 20, 2018, and August 30, 2019. We gathered results after 3 months of the intervention. Eighty-four outpatients on dialysis were verbally asked whether they were aware of any cognitive decline in themselves, such as forgetfulness and disorientation. Next, cognitive function tests were conducted on 14 patients who requested a detailed examination, indicating their motivation to participate in the study. One of the 14 participants was excluded because he had no cognitive impairment, and one was excluded due to the onset of another disease (Fig. 1). Therefore, the 12 participants in this study can be considered to be motivated. The inclusion criteria were (1) concern regarding a change in cognition, (2) impairment in one or more cognitive domains, (3) preservation of independence in functional abilities, and (4) no dementia [12]. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this trial. This study was registered with UMIN Clinical Trials. (UMIN000033742).

Interventions

We decided to provide cognitive training for patients with mild cognitive impairment who were undergoing hemodialysis and to examine its effectiveness by comparing their cognitive evaluations before and after a 3-month training period. In conjunction with hemodialysis, the patients underwent n-back training using the iPad mini 2. Training was performed on the iOS application “NBack for iPad, i-appli” for 20 min a day, thrice a week for three consecutive months (Fig. 2). N-back training involves working memory tasks utilizing short-term retention and processing of memory [13, 14]. Tasks are presented continuously, and responses are given by identifying the results of tasks n times ago in the activity. The number of consecutive correct answers and the value of n are used to evaluate users’ temporary memory ability. For example, in the case of a “one-back” task, the calculation of the second question is performed while remembering the answer of the first question, such that the calculation of the second question is based on the answer to the first question’s calculation result; therefore, the answer to the third question is calculated based on the calculation result of the second question. This study used the application in two modes: “flash” and “step.” In flash mode, the figure to be counted is displayed for a moment and disappears immediately. In addition to temporary memory capability, the ability to instantly count figures is required. In step mode, participants count the figures at their own pace, then press the button to move on to the next task. In this mode, the ability to instantly count figures is not necessary.

Hemodialysis treatments last approximately 4 h per session, and in 20–30% of dialysis sessions, patients experience a reduction in blood pressure at or immediately after the beginning of the treatment [15]. Therefore, the n-back training intervention was initiated about 60 to 120 min after a patient started dialysis, in consideration of a decrease in blood pressure. Discontinuation criteria were based on apparent vital sign abnormalities or patient refusal before the intervention.

Outcomes

Cognitive function measures

Global cognition was measured using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [16] and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Japanese version (MoCA-J) [17, 18]. Memory was measured using the Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT) [19]. Attention was measured using the Trail Making Test Part A (TMT-A) [20,21,22], a visual cancelation task (VCT) [23], the Symbol Digit Modality Test (SDMT) [23, 24], and the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT) [23, 25]. Executive function was measured using the TMT Part B (TMT-B) [20,21,22]. Patients were tested before receiving the intervention and after the 3-month training period.

Health measures

Indicators of patient health were also evaluated before and after the intervention. Blood test findings included albumin (Alb), C-reactive protein (CRP), hemoglobin (Hb), potassium (K), phosphorus (P), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (CRE), and Kt/V.

Statistical analysis

The patients were tested before and after a 3-month training period. Wilcoxon’s non-parametric test was used to analyze changes in cognitive function and the blood test results from before the intervention and immediately following the training period. In addition, the relationship between age and the amount of change in cognitive function measures were analyzed using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Effect sizes were calculated as r scores, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Patient background

The participants, who were 52–80-year-old patients undergoing outpatient hemodialysis at Syutaikai Hospital, included two males and ten females (N = 12). The duration of participants’ total dialysis course ranged from 5 to 248 months. The causes of kidney diseases were diabetic nephropathy (five patients), nephrosclerosis (three patients), and chronic glomerulonephritis (two patients), while in two patients, the condition was unknown. Angiotensin II receptor blockers were found in users (five patients) and non-users (seven patients). Involvement of Alzheimer’s disease was evaluated using magnetic resonance imaging and the voxel-based specific regional analysis system for Alzheimer’s disease (VSRAD). The participants’ mean value of atrophy within the volume of interest (VOI) was 0.67 ± 0.28, and none had brain atrophy suspected to be indicative of Alzheimer’s disease. The mean weight gain between dialysis in the month before the intervention was 2.34 ± 0.71 kg, and the mean weight gain between dialysis in the month after the intervention was 2.28 ± 0.84 kg (P = 0.04).

Cognitive function results

All 12 participants received the n-back training intervention using the iPad mini 2 and completed the 3-month training program. N-back training resulted in significant improvements in cognitive functioning as assessed by the MMSE (P = 0.01) and MoCA-J (P = 0.01), memory functioning as assessed by the BVRT (P = 0.02), executive functioning as assessed by the TMT-B (P = 0.01), and working memory as assessed by the PASAT (P = 0.01).

There was no significant improvement in the TMT-A and VCT, which assessed the selectivity of relatively simple visual attention. In addition, there was no significant improvement in SDMT scores. According to the participants, the training distracted them from hemodialysis, was enjoyable, and made time go by more quickly (Table 1).

Correlations between age and the amount of change in each cognitive function before and after the intervention were determined. The results showed that there were significant positive correlations between age and VCT-1 (r = 0.726), VCT-4 (r = 0.612), PASAT 2 s (r = 0.780), and PASAT 1 s (r = 0.759). No significant correlation was found between age and history of dialysis.

Blood test results

There were no significant differences in blood test results. Mean ± standard deviation values were 3.7 ± 0.2 g/dL pre-intervention and 3.7 ± 0.2 g/dL post-intervention (P = 0.35) for Alb; 0.1 ± 0.1 mg/dL pre-intervention and 0.2 ± 0.3 mg/dL post-intervention (P = 0.07) for CRP; 11.5 ± 1.0 g/dL pre-intervention and 11.6 ± 0.6 g/dL post-intervention (P = 0.67) for Hb; 4.9 ± 0.6 mEq/Lv pre-intervention and 4.5 ± 0.5 mEq/L post-intervention (P = 0.03, r = − 0.65) for K; 5.1 ± 0.7 mg/dL pre-intervention and 4.9 ± 1.0 mg/dL post-intervention (P = 0.43) for P; 64.9 ± 7.9 mg/dL pre-intervention and 63.8 ± 7.5 mg/dL post-intervention (P = 0.64) for BUN; 10.4 ± 1.3 mg/dL pre-intervention and 10.4 ± 1.4 mg/dL post-intervention (P = 0.64) for CRE; and 1.6 ± 0.3 pre-intervention and 1.7 ± 0.2 post-intervention (P = 0.50) for Kt/V.

Discussion

Cognitive training during hemodialysis

The results demonstrated the feasibility of administering cognitive training interventions to patients undergoing hemodialysis. Additionally, the intervention used in this study appears to have high safety, as there were no obvious vital sign abnormalities or rejections from individual participants compared to before the intervention. Regarding the ideal time to carry out cognitive training, there were no performance differences between 1 h before and the first hour of hemodialysis for any of the cognitive tests [26]. However, global cerebral blood flow declined significantly by 10 ± 15% between just before beginning hemodialysis and immediately after its conclusion [27]. This indicates that within the first half of dialysis treatment, cognitive function was not reduced, making it a suitable time for the training to be conducted. Our results indicate that administering the intervention during the first half of a dialysis session can be safe and successful. Attention should be paid to the latter part of the session because patients may experience a decrease in blood pressure and cerebral blood flow and an increase in fatigue.

A prior study reported that while intense exercise training on non-dialysis days is effective, exercise on hemodialysis days is also effective [28]. Owing to the intervention proposed in this study, patients had no need to visit the hospital on non-hemodialysis days, as they were engaging in cognitive training during hemodialysis. Patients also found it easy to continue the intervention for 3 months because it was administered simultaneously with their treatment; thus, no participants dropped out.

Effect of n-back training during hemodialysis

In our participants, VOI was 0.67 ± 0.28, and brain atrophy was not suspected to be indicative of Alzheimer’s disease. The pre-intervention mean MMSE score was 28.3 ± 1.4 points, and the VCT and SDMT pre-intervention scores were above the cutoff value for age 60. However, the mean MoCA-J score was 25.8 ± 2.1 points, and the PASAT 2 and 1-s scores were below the cutoff value for age 60. Therefore, the patients screened may not have had dementia; it could have been only mild cognitive impairment.

A prior n-back training study reported improvements in working memory and various cognitive functions in patients with reduced cognitive function [6]. In this study, MMSE, MoCA-J, BVRT, TMT-B, and PASAT 2 and 1-s scores all showed significant improvements after the 3-month intervention. The MMSE pre-intervention mean score was above the cutoff for dementia. Also, the MoCA-J pre-intervention score was below the cutoff for mild cognitive impairment. After the training, the mean MMSE score was 29.8 ± 0.8 points, while the mean MoCA-J score was 28.0 ± 1.6 points. These scores were above the cutoff value. Scores on the TMT-A, measuring attention function, did not improve, but those on the TMT-B, measuring the more complex executive function, improved after 3 months. In the PASAT, both the 2 and 1-s scores were improved after the intervention, with the former being above the cutoff value of 38% and the latter above the cutoff value of 23%. Therefore, n-back training during hemodialysis improved working memory. The relationship between age and the amount of change in each cognitive function before and after the intervention was confirmed, with a positive correlation between age and VCT-1, VCT-4, PASAT 2 s, and PASAT 1 s; the older the age, the greater the amount of change. This suggests that cognitive improvement may be obtained in old age even if the patient does not have dementia. The positive correlation with age suggests that the older adults had temporarily reduced reserve power, which may have been improved by the intervention. In addition, blood tests for Alb, CRP, Hb, P, BUN, CRE, and Kt/V, which may affect cognitive function, did not show any significant differences from before to after the intervention [2]. This suggests that n-back training is effective in improving cognitive function.

Limitations

This study had a small sample size, no control group, and was conducted over a limited period of 3 months. Therefore, the learning effect of the outcome could not be securely verified. In the future, it is necessary to establish a control group to verify the intervention effect.

Conclusion

Although our sample was small, motivated participants and cognitive training during hemodialysis improved cognitive and attention function in patients with mild cognitive impairment. The participants reported no negative effects of performing the n-back training. Although further research is needed to confirm these results with larger samples and follow-up studies are required to track its long-term impacts on health and quality of life outcomes, the non-invasive intervention tested in our study offers an easy and efficient way to engage hemodialysis patients at the most opportune time and ensure positive outcomes related to health and cognitive abilities.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Abbreviations

- Alb:

-

Albumin

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- BVRT:

-

Benton Visual Retention Test

- CRE:

-

Creatinine

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- K:

-

Potassium

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA-J:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Japanese version

- P:

-

Phosphorous

- PASAT:

-

Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task

- SDMT:

-

Symbol Digit Modality Test

- TMT-A:

-

Trail Making Test Part A

- TMT-B:

-

Trail Making Test Part B

- VCT:

-

Visual cancelation task

- VOI:

-

Volume of interest

- VSRAD:

-

Voxel-based specific regional analysis system for Alzheimer’s disease

References

Fresenius Medical Care. Fresenius medical care annual report. 2019. https://www.fresenius.com/fresenius-medical-care. Accessed 27 Mar 2020.

Etgen T. Kidney disease as a determinant of cognitive decline and dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-015-0115-4.

Murray AM, Tupper DE, Knopman DS, Gilbertson DT, Pederson SL, Li S, et al. Cognitive impairment in hemodialysis patients is common. Neurology. 2006;67:216–23. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000225182.15532.40.

Griva K, Stygall J, Hankins M, Davenport A, Harrison M, Newman SP. Cognitive impairment and 7-year mortality in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:693–703. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.003.

Drew DA, Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Scott T, Lou K, Kantor A, et al. Cognitive function and all-cause mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:303–11. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.009.

Takeuchi H, Taki Y, Kawashima R. Effects of working memory training on cognitive functions and neural systems. Rev Neurosci. 2010;21:427–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/revneuro.2010.21.6.427.

Matysiak O, Kroemeke A, Brzezicka A. Working memory capacity as a predictor of cognitive training efficacy in the elderly population. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2019.00126.

Soveri A, Antfolk J, Karlsson L, Salo B, Laine M. Working memory training revisited: a multi-level meta-analysis of n-back training studies. Psychon Bull Rev. 2017;24:1077–96. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1217-0.

Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Shah P. Short- and long-term benefits of cognitive training. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10081–6. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1103228108.

Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, et al. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3017–22. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015950108.

Suzuki T, Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Yoshida D, Ito K, et al. A randomized controlled trial of multicomponent exercise in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61483. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061483.

Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med. 2004;256:183–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x.

Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Perrig WJ. Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6829–33. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801268105.

Au J, Sheehan E, Tsai N, Duncan GJ, Buschkuehl M, Jaeggi SM. Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory: a meta-analysis. Psychon Bull Rev. 2015;22:366–77. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-014-0699-x.

Palmer BF, Henrich WL. Recent advances in the prevention and management of intradialytic hypotension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:8–11. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2007091006.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

Fujiwara Y, Suzuki H, Yasunaga M, Sugiyama M, Ijuin M, Sakuma N, et al. Brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment in older Japanese: validation of the Japanese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2010;10:225–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00585.x.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x.

Benton A. The revised visual retention test: clinical and experimental applications. 3rd ed. Cleveland: The Psychological Corporation; 1963.

Reitan RM. The relation of the Trail Making Test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol. 1955;19:393–4. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0044509.

Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8:271–6. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1958.8.3.271.

Tombaugh TN. Trail Making Test A and B: normative data stratified by age and education. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19:203–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8.

Committee JS for HBDBFT. Clinical Assessment for Attention (CAT). Clinical Assessment for Spontaneity (CAS). Tokyo: Shinkoh Igaku Shuppansha; 2006.

Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual–revised. Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles; 1982.

Gownwald D. Paced Auditory Serial-Addition Task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Percept Mot Skills. 1977;44:367–73. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367.

Drew DA, Tighiouart H, Scott TM, Lou KV, Shaffi K, Weiner DE, et al. Cognitive performance before and during hemodialysis: a randomized cross-over trial. Nephron Clin Pract. 2013;124:151–8. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356393.

Polinder-Bos HA, García DV, Kuipers J, Elting JWJ, Aries MJH, Krijnen WP, et al. Hemodialysis induces an acute decline in cerebral blood flow in elderly patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:1317–25. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2017101088.

Konstantinidou E, Koukouvou G, Kouidi E, Deligiannis A, Tourkantonis A. Exercise training in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis: comparison of three rehabilitation programs. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:40–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/165019702317242695.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the staff at the Syutaikai Hospital Dialysis Center.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YN conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YN, MI, and MM mainly collected samples and analyzed and interpreted the patient data. TI and NK managed hemodialysis patients during the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Syutaikai Hospital Ethical Committee (approval number 2018-09). This protocol was also retrospectively registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000033742).

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Noguchi, Y., Ito, M., Mushika, M. et al. The effect of n-back training during hemodialysis on cognitive function in hemodialysis patients: a non-blind clinical trial. Ren Replace Ther 6, 38 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-020-00288-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-020-00288-7