Abstract

Background

This study aimed to explore the role of patient’s characteristic and haematological factors as predictive on the maturation of arteriovenous fistulae in patients who underwent vascular access surgery at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

Methods

Retrospective data from 300 patients who had undergone fistula creation between February 2007 and October 2010 was examined. A predictive logistic regression model was developed using the backward stepwise procedure. Model performance, discrimination and calibration, was assessed using the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve and Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness of fit test.

Results

Three variables were identified which independently influenced fistula maturation. Males were twice as likely to undergo fistula maturation, compared to that of females (odds ratio (OR) 0.514; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.308–0.857), patients with no evidence of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) were three times more likely to mature their fistula (OR 3.140; 95% CI 1.596–6.177) and a pre-operative vein diameter > 2.5 mm resulted in a fivefold increase in fistula maturation compared to a vein size less than 2.5 mm (OR 4.532; 95% CI 2.063–9.958). The model for fistula maturation had fair discrimination as indicated by the area under the ROC curve (0.68; 95% CI 0.615–0.738) but good calibration indicated by Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p = 0.79).

Conclusion

Gender, PVD and vein size are independent predictors of arteriovenous fistula maturation. The clinical utility of these risk equation in the maturation of arteriovenous fistulae requires further validation in the newly treated patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a critical condition with considerable public health implications. It affects a significant proportion of the general population and, when progressive, has an increasing influence on morbidity and mortality. In the USA, it is reported that 10% (more than 20 million adults) are affected with CKD [1]. In the UK, the prevalence of stage 3–5 CKD is 1.7 million adults [2] with an annual incidence of stage 5 CKD of 100 per million of the population [3]. Once a patient reaches end-stage kidney disease, their quality of life becomes poor and the life expectancy is considerably shortened [4]. According to the United States Renal Data System [5], more than 87,000 people die from causes related to kidney failure each year.

Through the provision of renal replacement therapy, survival and quality of life of the patients can be markedly improved [6]. The efficiency of haemodialysis treatment relies on a functional status of vascular access, and complications here represent the main factor that determines a rise in the morbidity among haemodialysis patients and consequently, a rise in the healthcare expenses [7]. In the UK, renal replacement therapy utilizes up to 2% of its financial resources [8]. To ensure that the dialysis therapy can be efficiently undertaken, all patients have to have a fully developed fistula appropriate for cannulation. The percentage of arteriovenous fistulae (AVF) that fail to mature for haemodialysis is 28–53% [9]. The dialysis therapy is often postponed for up to 6 months or more to allow extra time for the fistula to develop; if this does not happen, the AVF is declared as ‘failed to mature’. The development process of AVF is complicated, and it is difficult to settle on the precise length of time it requires to mature [10]. Several researchers [11,12,13,14,15,16] have recommended a number of pre-surgical principles relying on invasive and non-invasive procedures; however, factors, such as cost, time and complexity, hinder the widespread application of these principles.

It may be possible to improve the end results of vascular access by gaining a more comprehensive picture about the various factors involved in the maturation of fistulae. This could then in turn provide important information during the pre-surgical evaluation that surgeons can base their decisions on. Independent predictive factors may be beneficial in anticipating successful fistula maturation without the use of invasive tests, and this could be cost-effective. The objective of the study was to assess factors which are important in the successful maturation of AVF. These were used to formulate a simple and economical prognostic model on the maturation of AVF.

Methods

Research design

This is a single-centre exploratory study that involved the collection of retrospective data from the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh and identification of those independent predictors for a predictive model of fistula maturation. A favourable ethical opinion was obtained from the NHS Lothian ethics committee and Queen Margaret University ethics committee for the study.

Using the retrospective clinical database of patients with ESRD, we identified 300 patients between February 2007 and October 2010 who had undergone vascular access surgery for first-time AVF creation. Patients who underwent a repeat AVF creation (second and further fistula creations) were not included in this study. Purposive sampling technique was used for patient’s recruitment. Study was performed systematically in different steps from identification, screening, recruitment, data collection of potential participants and finally data analysis by using appropriate statistical test (Fig. 1).

A retrospective case note review was performed on all patients identified from the hospital vascular access database as having undergone construction of AVF. The medical case files of the patients who had undergone fistula surgery between 2007 and 2010 were retrieved from the medical records (Proton® software and Apex® software) at the Royal Infirmary Edinburgh. At the beginning, all potential participants’ records were screened comprehensively. From the data, reports of patients were developed from the pre-operative assessment papers and the clinical results of their operation obtained from the clinical records and follow-up case notes.

The details of patient’s factor and blood markers were explored by complete review of the patient’s inpatient and outpatient medical record (containing all information pertaining to medical and surgical consultations and all previous hospital admissions and management) via an electronic database. All the data was entered into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, USA).

The patient record including age, gender and risk factors; peripheral vascular disease (PVD); diabetes mellitus (DM); hypertension (HTN); smoking (ever versus never); and dialysis (ever versus never). Patients were defined as obese when their body mass index was > 30, consistent with the World Health Organization classification [17]. Fistula characteristics that were ascertained included fistula type and its location (right or left). Clinically important biomedical factors including estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR); creatinine; blood urea; serum potassium (K); sodium (Na); calcium (Ca); bicarbonate (HCO3); prothrombin time (PT); international normalization ratio (INR); high-density lipoprotein (HDL); triglyceride (TG); total cholesterol (TC); and vein diameter were also included in the analysis. Duplex investigation of the veins was performed to measure the diameter of arm veins according to a standard protocol by vascular scientists in the vascular clinic of Royal Infirmary Edinburgh. All procedures such as general physical examination consisted of inspection and palpation of the vessels of the upper arm and forearm and measurement of brachial artery blood pressure. Subsequently, height and weight details were recorded in order to calculate the BMI values and blood samples were obtained by the regular NHS staff. PVD was identified through a physical examination and by comparing the blood pressure in the arm and ankle. Ankle-brachial pressure index (ABPI) ≤ 0.90 reliably identifies 95% of symptomatic arteriogram-positive PVD individuals and almost 100% of healthy controls [18].

Outcome definition

Maturation was defined as the ability to provide on-going functional haemodialysis at the sixth week [19, 20] from the access procedure. An experienced dialysis specialist nurse determined when the fistula was ready for an attempt at cannulation and then attempted initial cannulation of the fistula; if unsuccessful, the fistula then was evaluated by the vascular surgeon at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0). Data was expressed as mean, standard deviation (SD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) or as proportions. The association between the independent factors and outcome, i.e. mature fistula, was assessed initially employing univariable logistic regression, and following this, a multivariable model was produced utilizing backward stepwise logistic regression with those variables found to be significant in the univariable regression at p < 0.25. The odds ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals for variables in the final model were reported. The significance level for the multivariable model was set at p < 0.05. Multicollinearity in the model was investigated to assess the relationship between the independent factors. We evaluated the calibration and discrimination performance of the model. For the calibration, the Hosmer-Lemeshow test was employed to investigate how well the predicted probabilities agreed with the observed probabilities. Discrimination, which refers to the ability of a model to distinguish between the maturation and immaturation of the AVF, was quantified using the ROC curve. The ROC curve plots the sensitivity (true positive rate) against 1—specificity (false positive rate) for consecutive cut-offs for the probability of an outcome [21].

Results

Retrospective data was obtained for 300 patients who underwent vascular access surgery. Ages ranged from 19 to 87 years, with a mean age of 60.5 (16) years. Successful maturation of the AVF was achieved in 168 (56%) patients as assessed by dialysis specialist nurses.

Univariable associations

AVF characteristics and univariable analysis of clinical variables for the prediction of maturation of fistula are shown in Table 1. Univariable analysis found nine variables to be associated with maturation of AVF: gender, side of arm, type of fistulae, PVD, diabetes, SBP, INR, TG and vein size. In addition to the above variables, a further two statistically non-significant variables, i.e. dialysis [22, 23] (ever versus never) and eGFR [24], were added to the model due to their possible clinical association with the maturation of AVF as suggested by the vascular surgeons.

Multivariable associations

Three variables were identified which were independently associated with fistula maturation using multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2). Males were twice as likely to undergo fistula maturation, compared to females (OR 0.514; 95% CI 0.308–0.857; p = 0.011) with patients who had no evidence of PVD being three times more likely to mature their fistula (OR 3.140; 95% CI 1.596–6.177; p < 0.001) and those with a pre-operative vein diameter greater than 2.5 mm [25, 26] resulting in a fivefold increase in fistula maturation compared to a vein size less than 2.5 mm (OR 4.532; 95% CI 2.063–9.958; p < 0.001). No multicollinearity was observed between the independent factors.

The overall risk score for each patient was estimated by summing the scores of each significant independent variable. Using the prediction model, the following prognostic equation was developed:

where β0 is the intercept, β1 till β n are the regression coefficients and X1 to X n are independent variables.

where all variables are coded 0 for no or 1 for yes. The value − 0.182 is called the intercept, and the other numbers are the estimated regression coefficients for the predictors, which indicate their mutually adjusted relative contribution to the outcome risk.

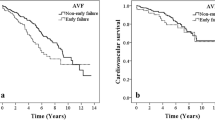

The performance of the final prognostic model assessed in terms of calibration using Hosmer-Lemeshow test was not significant (p = 0.79). This suggests that there was no statistically significant difference between predicted and observed outcomes. The area under the ROC curve for prediction of maturation of fistula was 0.68 (95% bias-corrected CI 0.615, 0.738), which indicates fair [27] discrimination (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The results of this study identify three clinical factors, each of which was independently associated with maturation of AVF: male gender, PVD and vein diameter. AVF successfully matured in 168 patients, accounting for 56% of the total number of patients. Similar results have been obtained by Feldman et al. [28], with 55.5% out of a total of 348 patients exhibiting successful AVF maturation.

The study result showed a gender difference, mature rates of 60% for men and of 48% for women. Miller et al. [29] found Ithat the AVF maturation is more successful in men than in women. Similar results were obtained by Gibbons [30] and Iyem [31]. In our study, males were twice as likely to undergo fistula maturation, compared to that of females; the most rational explanation for this difference is the smaller size of vessels in women. Some studies also found female gender to be associated with immature fistula [12, 13, 15, 32]. However, there are also studies that did not show a gender difference. Jennings et al. [26] involved the creation of AVFs on 114 participants and did not observe any gender difference in the maturation of AVF [33, 34].

Out of 300 patients, 38% were diabetic and 16% had clinical evidence of PVD. In a number of studies, it has been reported that more than 50% of North American dialysis patients had diabetes, and approximately one third had PVD [35,36,37]. In our study, fistula maturation was 59.7% in a group with no history of PVD and 33.3 in patients with PVD. This emerged as one of the predictive factors in the maturation of fistulae in the multivariable analysis. Patients with no evidence of PVD were three times more likely to mature their fistula. Our data is consistent with other studies in which PVD was associated with AVF failure [38, 39]. Chan et al. conducted a retrospective cohort analysis using 1486 patients’ data [40]. It was revealed that patients who suffer from PVD are more likely to experience non-maturation of AVF (OR 2.78, 95% CI 1.01–7.63, p = 0.047). Fistula failure is consistent with the underlying need for adequate arterial vessels, which deteriorate with the normal aging process and are damaged by concurrent disease; this finding is supported by other studies [11, 41].

Our data are consistent with other studies in which vein size was associated with successful maturation of fistulae. Mendes et al. reported that if the diameter of the cephalic veins exceeds 2 mm, there is a 76% success rate of functional dialysis access, whereas if the diameter is less than 2 mm, there is only a 16% success rate [14]. In this study, a pre-operative vein diameter greater than 2.5 mm resulted in a fivefold increase in fistula maturation compared to a vein size less than 2.5 mm. Our data is consistent with other studies in which vein size is associated with successful fistula maturation [41, 42]. The cut-off value identified by Brimble et al. was 2.6 mm; however, only women exhibited a substantial discrepancy between AVF success and failure with regard to vein diameter [43]. In contrast, Wong et al. did not observe any discrepancies between AVF success and failure in the mean vein diameter at the wrist but indicated AVF failure in all cases where the vein diameter was below 1.6 mm [44].

This study hypothesized that blood and patient factors could be used to stratify risk of self-report of maturation of AVF. In brief, using the development dataset of 300 subjects, we identified three variables associated with maturation of fistula: gender, PVD and vein size. The performance of the developed model in this study was assessed by discrimination and calibration of the model. The area under the ROC curve for a prognostic model is classically between 0.6 and 0.85 [45]. In our study, ROC curve was primarily designed for prognostic models, rather for diagnostic models. ROC curve was 0.68 in the development model and 0.59 in the validation stage, meaning that the model had limited capacity to correctly distinguish between mature and immature fistulae.

The present study has a number of limitations. The connection between artery diameter and blood inflow rate was emphasized by a number of studies [42, 46, 47]. However, we did not included artery diameter and arterial blood flow in our study due to the unavailability of retrospective data. Another limitation were the duplex measurements of the vein diameter and measurements of vessel diameter carried out by vascular scientists who had a great deal of experience and were familiar with the procedure. The objective of the scientist was to carry out the measurements in spite of the differences between pre-surgery examination and the actual intervention. However, there were few staff changes during the 5 years when the fistulae were constructed. As argued by Pisoni et al. [48], it is important to take into consideration non-measurable elements, such as measurement techniques and principles of care, apart from ample case-mix adaptations highlighted by other studies.

Conclusion

A preoperative, clinical prediction model to determine fistulae that are likely to mature was created. It was found to be simple and easily reproducible and applied to predictive risk categories. Gender, PVD and vein size are useful predictors of arteriovenous fistula maturation. The clinical utility of these risk categories in the maturation of arteriovenous fistula requires further validation in the newly treated patients.

Abbreviations

- ABPI:

-

Ankle-brachial pressure index

- AVF:

-

Arteriovenous fistula

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- ESRD:

-

End-stage renal disease

- HCO3 :

-

Bicarbonate

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- K:

-

Potassium

- Na:

-

Sodium

- NHS:

-

National Health System

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- PVD:

-

Peripheral vascular disease

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating curve

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for the Social Science

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- USRDS:

-

United States Renal Data System

References

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National chronic kidney disease fact sheet: general information and national estimates on chronic kidney disease in the United States. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014.

NHS Kidney Care. Kidney Disease: Key Facts and Figures. [Online]. East Midlands Public Health Observatory (EMPHO), East Midlands. 2011. Available from: http://patientsafety.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/diabeteswithkidneydiseasekeyfacts.pdf. Accessed May 2014.

Hamer RA, El Nahas AM. The burden of chronic kidney disease: Is rising rapidly worldwide. BMJ :British Medical Journal. 2006;332(7541):563–564.

Noble H, Lewis R. Acceptance and rejection of dialysis—the need for patient evaluation. Journal of renal care 2008;34(1):45. Epub 2008/03/14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-6686.2008.00011.x. PubMed PMID: 18336524.

(System) UURD. Annual data report: atlas of chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD. 2011.

Mazzuchi N, Carbonell E, Fernandez-Cean J. Importance of blood pressure control in hemodialysis patient survival. Kidney Int 2000;58(5):2147–2154. Epub 2000/10/24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2000.00388.x. PubMed PMID: 11044236.

NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management. NICE clinical guideline 73. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2014.

NICE, National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic kidney disease: early identification and management of chronic kidney disease in adults in primary and secondary care. NICE clinical guideline 73. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008.

Asif A, Cherla G, Merrill D, Cipleu CD, Briones P, Pennell P. Conversion of tunneled hemodialysis catheter-consigned patients to arteriovenous fistula. Kidney Int 2005;67(6):2399–2406. Epub 2005/05/11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00347.x. PubMed PMID: 15882285.

Corpataux JM, Haesler E, Silacci P, Ris HB, Hayoz D. Low-pressure environment and remodelling of the forearm vein in Brescia–Cimino haemodialysis access. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17(6):1057–62. Epub 2002/05/29. PubMed PMID: 12032197.

Feldman HI, Joffe M, Rosas SE, Burns JE, Knauss J, Brayman K. Predictors of successful arteriovenous fistula maturation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(5):1000–12. Epub 2003/10/29. PubMed PMID: 14582044.

Huber TS, Ozaki CK, Flynn TC, Lee WA, Berceli SA, Hirneise CM, et al. Prospective validation of an algorithm to maximize native arteriovenous fistulae for chronic hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36(3):452–9. Epub 2002/09/10. PubMed PMID: 12218966.

Lok CE, Allon M, Moist L, Oliver MJ, Shah H, Zimmerman D. Risk equation determining unsuccessful cannulation events and failure to maturation in arteriovenous fistulas (REDUCE FTM I). J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17(11):3204–3212. Epub 2006/09/22. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2006030190. PubMed PMID: 16988062.

Mendes RR, Farber MA, Marston WA, Dinwiddie LC, Keagy BA, Burnham SJ. Prediction of wrist arteriovenous fistula maturation with preoperative vein mapping with ultrasonography. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36(3):460–3. Epub 2002/09/10. PubMed PMID: 12218967.

Robbin ML, Chamberlain NE, Lockhart ME, Gallichio MH, Young CJ, Deierhoi MH, et al. Hemodialysis arteriovenous fistula maturity: US evaluation. Radiology 2002;225(1):59–64. Epub 2002/10/02. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2251011367. PubMed PMID: 12354984.

Rooijens PP, Burgmans JP, Yo TI, Hop WC, de Smet AA, van den Dorpel MA, et al. Autogenous radial-cephalic or prosthetic brachial-antecubital forearm loop AVF in patients with compromised vessels? A randomized, multicenter study of the patency of primary hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(3):481–486; discussions 7. Epub 2005/09/21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2005.05.025. PubMed PMID: 16171591.

World Health Organisation. Global database on basal metabolic index. 2004. [online]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html. Accessed 12 Sept 2016.

Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg. 2007;45 Suppl S:S5–67. Epub 2007/01/16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.037. PubMed PMID: 17223489.

Clinical practice guidelines for hemodialysis adequacy, update 2006. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48 Suppl 1:S2–90. Epub 2006/07/04. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.03.051. PubMed PMID: 16813990.

Patel ST, Hughes J, Mills JL Sr. Failure of arteriovenous fistula maturation: an unintended consequence of exceeding dialysis outcome quality initiative guidelines for hemodialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(3):439–45. discussion 45. Epub 2003/08/30. PubMed PMID: 12947249.

Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, Gerds T, Gonen M, Obuchowski N, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology. 2010;21(1):128–138. Epub 2009/12/17. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c30fb2. PubMed PMID: 20010215; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3575184.

Weale AR, Bevis P, Neary WD, Boyes S, Morgan JD, Lear PA, et al. Radiocephalic and brachiocephalic arteriovenous fistula outcomes in the elderly. J Vasc Surg 2008;47(1):144–150. Epub 2008/01/08. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2007.09.046. PubMed PMID: 18178467.

Zeebregts C, van den Dungen J, Bolt A, Franssen C, Verhoeven E, van Schilfgaarde R. Factors predictive of failure of Brescia-Cimino arteriovenous fistulas. Eur J Surg 2002;168(1):29–36. Epub 2002/05/23. https://doi.org/10.1080/110241502317307544. PubMed PMID: 12022368.

Jindal K, Chan CT, Deziel C, Hirsch D, Soroka SD, Tonelli M, et al. Hemodialysis clinical practice guidelines for the Canadian Society of Nephrology. J Am Soc Nephrol 2006;17(3 Suppl 1):S1–27. Epub 2006/02/25. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2005121372. PubMed PMID: 16497879.

Jennings WC. Creating arteriovenous fistulas in 132 consecutive patients: exploiting the proximal radial artery arteriovenous fistula: reliable, safe, and simple forearm and upper arm hemodialysis access. Arch Surg. 2006;141(1):27–32; discussion Epub 2006/01/18. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.141.1.27. PubMed PMID: 16415408.

Jennings WC, Kindred MG, Broughan TA. Creating radiocephalic arteriovenous fistulas: technical and functional success. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208(3):419–425. Epub 2009/03/26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.015. PubMed PMID: 19318004.

Brubaker PH. Do not be statistically cenophobic: time to roc and roll! J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2008;28(6):420–421. Epub 2008/11/15. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0b013e31818c3c9f. PubMed PMID: 19008699.

Feldman HI, Held PJ, Hutchinson JT, Stoiber E, Hartigan MF, Berlin JA. Hemodialysis vascular access morbidity in the United States. Kidney Int 1993;43(5):1091–1096. Epub 1993/05/01. PubMed PMID: 8510387.

Miller PE, Tolwani A, Luscy CP, Deierhoi MH, Bailey R, Redden DT, et al. Predictors of adequacy of arteriovenous fistulas in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 1999;56(1):275–280. Epub 1999/07/20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00515.x. PubMed PMID: 10411703.

Gibbons CP. Primary vascular access. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2006;31(5):523–529. Epub 2005/11/22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.10.006. PubMed PMID: 16298148.

Iyem H. Early follow-up results of arteriovenous fistulae created for hemodialysis. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2011;7:321–325. Epub 2011/06/03. doi: https://doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.s14277. PubMed PMID: 21633522; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3104609.

Peterson WJ, Barker J, Allon M. Disparities in fistula maturation persist despite preoperative vascular mapping. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(2):437–441. Epub 2008/02/01. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.03480807. PubMed PMID: 18235150; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2390953.

Ekicei Y, Karayalı FY, Yagmurdur FC. Snuff-box arteriovenous fistula for haemodialysis. Turkish VascSurg. 2008;17:73–9.

Palmes D, Kebschull L, Schaefer RM, Pelster F, Konner K. Perforating vein fistula is superior to forearm fistula in elderly haemodialysis patients with diabetes and arterial hypertension. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26(10):3309–3314. Epub 2011/02/18. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfr004. PubMed PMID: 21325347.

Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction. Circulation 2007;115(7):928–935. Epub 2007/02/21. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.106.672402. PubMed PMID: 17309939.

Mendelssohn DC, Ethier J, Elder SJ, Saran R, Port FK, Pisoni RL. Haemodialysis vascular access problems in Canada: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS II). Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21(3):721–728. Epub 2005/11/29. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfi281. PubMed PMID: 16311264.

Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr., D’Agostino RB, Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27(2):157–172; discussion 207–12. Epub 2007/06/15. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2929. PubMed PMID: 17569110.

Obialo CI, Tagoe AT, Martin PC, Asche-Crowe PE. Adequacy and survival of autogenous arteriovenous fistula in African American hemodialysis patients. ASAIO J 2003;49(4):435–439. Epub 2003/08/16. PubMed PMID: 12918587.

Woods JD, Turenne MN, Strawderman RL, Young EW, Hirth RA, Port FK, et al. Vascular access survival among incident hemodialysis patients in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 1997;30(1):50–57. Epub 1997/07/01. PubMed PMID: 9214401.

Chan MR, Young HN, Becker YT, Yevzlin AS. Obesity as a predictor of vascular access outcomes: analysis of the USRDS DMMS wave II study. Semin Dial 2008;21(3):274–279. Epub 2008/04/10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-139X.2008.00434.x. PubMed PMID: 18397205.

Lauvao LS, Ihnat DM, Goshima KR, Chavez L, Gruessner AC, Mills JL, Sr. Vein diameter is the major predictor of fistula maturation. J Vasc Surg 2009;49(6):1499–1504. Epub 2009/06/06. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.018. PubMed PMID: 19497513.

Khavanin Zadeh M, Gholipour F, Naderpour Z, Porfakharan M. Relationship between vessel diameter and time to maturation of arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis access. Int J Nephrol. 2012;2012:942950. Epub 2011/12/22. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/942950. PubMed PMID: 22187645; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3236464.

Brimble KS, RabbatCh G, Treleaven DJ. Utility of ultrasono-graphic venous assessment prior to forearm arteriovenous fistula creation. ClinNephrol. 2002;58:122–7.

Wong V, Ward R, Taylor J, Selvakumar S, How TV, Bakran A. Factors associated with early failure of arteriovenous fistulae for haemodialysis access. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1996;12(2):207–213. Epub 1996/08/01. PubMed PMID: 8760984.

Royston P, Moons KG, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ 2009;338:b604. Epub 2009/04/02. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b604. PubMed PMID: 19336487.

Huijbregts HJ, Bots ML, Wittens CH, Schrama YC, Blankestijn PJ. Access blood flow and the risk of complications in mature forearm and upper arm arteriovenous fistulas. Blood Purif 2009;27(2):212–219. Epub 2009/01/30. https://doi.org/10.1159/000197561. PubMed PMID: 19176950.

Monroy-Cuadros M, Yilmaz S, Salazar-Banuelos A, Doig C. Risk factors associated with patency loss of hemodialysis vascular access within 6 months. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(10):1787–1792. Epub 2010/06/26. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.09441209. PubMed PMID: 20576823; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2974378.

Pisoni RL, Young EW, Dykstra DM, Greenwood RN, Hecking E, Gillespie B, et al. Vascular access use in Europe and the United States: results from the DOPPS. Kidney Int 2002;61(1):305–316. Epub 2002/01/12. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00117.x. PubMed PMID: 11786113.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Rona Lochiel, a vascular access nurse specialist, Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh, for her assistance in the recruitment and follow-up of the patients. We also like to thank statistician Catriona Graham (Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, University of Edinburgh) for her advice in the data analysis.

Funding

No funding was obtained.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAS conceived the study and collected the data. MAS and RR analysed the data. MAS and SA drafted the manuscript while DS, TC and ZR revised and reviewed the whole manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the South East Scotland Research Ethics Committee 03, Edinburgh, UK (No: 09/S1103/29).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Siddiqui, M.A., Ashraff, S., Santos, D. et al. Development of prognostic model for fistula maturation in patients with advanced renal failure. Ren Replace Ther 4, 11 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-018-0153-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41100-018-0153-z