Abstract

Background

Pituitary adenoma (PA) is a common intracranial tumor and surgical treatment is considered to be the best treatment for most patients. The extended endoscopic endonasal approach (EEEA) has been used to treat increasing numbers of patients with PA in recent years. We conducted this study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of this approach for PA resection.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent an EEEA to remove PA by a binostril, four-handed technique between October 2013 and April 2016 in our department. The medical information of the patients including gender, age, tumor size, hormone level, clinical outcome, and complications were collected and analyzed.

Results

From a total of 593 pituitary adenoma surgeries, 171 patients (101 male and 70 female, mean age 47.4 ± 12.8 years) underwent EEEA, including 96 with functional adenomas (56.14%) and 75 with nonfunctional adenomas (43.86%). The most common symptoms were headache and vision change. Gross total resection was achieved in 126 patients (73.68%). Common complications were hyposmia or anosmia, diabetes insipidus, hypopituitarism, postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leak, cerebral hemorrhage, and epistaxis. The mean duration of follow-up was 14.6 months (range: 6–31 months).

Conclusions

The application of EEEA for PA resection by a binostril, four-handed technique provided great surgical freedom with minimal invasion, and resulted in few complications. EEEA is a secure and effective surgical method that could be used for the majority of PAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pituitary adenoma (PA) is common in the general population. According to a previous epidemiology study, about 16.7% of the general population show changes in the pituitary gland [1]. PA can be classified by diameter and divided into microadenomas (<1 cm), macroadenomas (1–4 cm), or giant adenomas (>4 cm) [1, 2].Depending on endocrinological status, PA can be classified as nonfunctioning or functioning. Functioning PA may be further divided into prolactin-secreting (PRL), growth hormone-secreting (GH), gonadotropin-secreting, adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting (ACTH), thyroid-stimulating hormone-secreting (TSH), and multiple hormone-secreting forms.

Surgical treatment is considered the primary therapy in nonfunctioning PA, GH-secreting, ACTH-secreting, gonadotropin-secreting, and TSH-secreting PAs [3]. For PRL-secreting PA, while medical therapy constitutes the primary treatment, surgery is an option for patients who are intolerant or resistant to drugs, have pituitary apoplexy, or tumor progression under medical therapy [3,4,5]. Surgery of PA has improved over the last 100 years to reduce trauma and complications, and improve the postoperative outcome. Horsley reported the first resection of a pituitary tumor by open craniotomy in 1887 [6]. Schloffer et al. first described the transsphenoidal approach in a sellar tumor in 1907 [7]. In the 1960s, the operation microscope was introduced during transsphenoidal procedures by Hardy and was quickly adopted for clinical neurosurgical practice [8]. Since then, the use of a transsphenoidal microscope for pituitary surgery is considered the gold standard [9]. In 1963, Gerard Guito introduced the use of an endoscope during transsphenoidal procedures to provide an overview of the contents of the sellar turcica [10]. In 1992, Jankowski et al. first used endoscopy for the resection of PA, and pure transsphenoidal endoscopic PA surgery was described later by Jho and Carrau [11, 12]. Over the last two decades, following the development of optical techniques, endoscopic endonasal surgery for PAs has been progressively accepted by many neurosurgeons and has become popular in many clinical centers. Increasing numbers of neurosurgeons now choose the endoscopic endonasal approach as the first option to resect PA, due to the wider visualization and reduced trauma [13,14,15,16]. However, the standard transsphenoidal approach fails to expose PAs invading the anterior cranial base, cavernous sinus, and clivus [17]. Therefore, continuous efforts have been made to improve surgical techniques. Several of these attempts have reported the application of extended endoscopic endonasal approach (EEEA), which removes the PA, with minimal invasiveness and low numbers of complications [17, 18].

Methods

Study Design

From October 2013 to April 2016, those patients who underwent an EEEA for a PA surgery in the Neurosurgery Department of Wuhan Union Hospital met our inclusion criteria. All the patients underwent an assessment of preoperative endocrinologic and neuroimaging (including magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] with contrast of pituitary and computed tomography [CT] of nasopharynx). An endocrinologic test, performed before and after the operation, consisted of sexual hormones, cortisol at 8 AM and 4 PM, free triiodothyronine, free thyroxine, TSH, and GH. The patients were followed-up from 6 to 31 months, (mean, 14.6 months). The medical information of the patients were reviewed to collected demographic data, including gender, age, clinical symptoms, hormonal level, tumor size, clinical outcome, and complications.

Surgical technique

Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position without routine rigid fixation of the head. The surgeon and the assistant were both positioned on the right side of the patient. After strict sterilization of the nasal cavity and oral cavity, cotton pieces soaked with adrenalin were used to contract blood vessels and enlarge the nasal cavity. The operation is usually performed using a binostril route with a 0° rigid endoscope. Once the endoscope is inserted into the nostril, the inferior turbinate and nasal septum is visible. Then the middle turbinate was lateralized to increase the surgical corridor, and the sphenoid sinus ostium, a key anatomic landmark, could be seen 1.0–1.5 cm above the sphenoethmoid recess. The posterior nasal septum was removed to link the bilateral nasal cavities and increase the working space, and the anterior wall and partial septum of sphenoid sinus were removed together (Fig. 1).

The route of the EEEA at the nasal rhinal stage. a: The middle turbinate (MT) and nasal septum (NS). b: The middle turbinate has been lateralized. c: The sphenoid sinus ostium (SSO) is present between the superior turbinate (ST) and nasal septum. d: After resection of the partial nasal septum, the right nasal cavity (RNC) and left nasal cavity (LNC) were linked together

After removal of the residual septum of the sphenoid sinus, the dura was opened with a cruciate incision, and the tumor was resected piece-by-piece with a curette, tweezers, and aspirator. After removal of the tumor, we used gelfoam to block the surgical cavity, and a neuropatch was placed within the dural defect. If a postoperative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak was foreseeable, more material is used to reconstruct the skull base, including autologous fascia and fat of the musculi quadriceps femoris, vascularized pedicled nasoseptal flap, and fibrin glue. Finally, a meche and a catheter with an aqueous capsule were used to support the skull base, and were removed several days later (Fig. 2).

Results

The study sample comprised 101 men and 70 women, with a mean age of 47.4 ± 12.8 years with a range of 15–71 years. All the patients with PRL-secreting PA had failed medical therapy before surgery or had a pituitary apoplexy. The mean tumor volume in our study was 8.752 ± 12.53 cm3, with 20 microadenomas (11.70%), 133 macroadenomas (77.78%) and 18 giant adenomas (10.52%).

The main symptoms at diagnosis were headache (65 patients, 38.01%), visual impairment (visual loss, diplopia, and visual field defect in 64 patients, 37.43%), menstrual disorder or lactation (27 patients, 15.79%) and acromegaly (9 patients, 5.26%). In addition, 18 patients (10.53%) were diagnosed incidentally without any obvious symptoms (Table 1).

Gross total resection (GTR) was achieved in 126 patients (73.68%), including 20 microadenomas, 102 macroadenomas, and 4 giant adenomas. Based on the functional classification, GTR was achieved in 68 functional adenomas (28 in PRL-secreting, 7 in GH-secreting, 5 in gonadotropin-secreting, 2 in ACTH-secreting, 2 in TSH-secreting and 24 in multiple hormone-secreting) and 58 nonfunctional adenomas (Table 2). There were 4 patients who underwent a second microscope or endoscopic surgery and 11 patients received postoperative gamma knife treatment.

The symptoms of 144 patients (95.36%) were significantly improved or had disappeared in 151 patients (20 patients did not have any obvious symptoms). Surgery-related complications were reported in 55 cases (32.16%), including hypopituitarism (6 patients, 3.51%), postoperative CSF leak (3 patients, 1.75%), diabetes insipidus temporary (14 patients, 8.19%), hyposmia or anosmia (24 patients, 14.04%), cerebral hemorrhage (4 patients, 2.34%), and epistaxis (4 patients, 2.34%, Table 3). The most common postoperative complication was hyposmia or anosmia. All the patients underwent an examination of pituitary relative hormone within 1 week after operation. Relative hormone levels were reduced in 40 patients (23.39%), but of these, only 6 required long-term hormone replacement therapy, because the other patients recovered normal hormone levels quickly. Hyposmia and anosmia also slowly recovered in most patients. Obvious postoperative CSF leak occurred in 3 patients, one of which underwent a successful repair surgery, and two others who recovered with expected treatment, and all of them recovered with no intracranial infection. The autologous fascia was used in 20 patients to avoid CSF leak. We also observed one death in our study.

Discussion

Surgical technique

Over the last two decades, surgery with an endoscopic approach for PA has come into prominence and slowly reached favor globally. Compared with the traditional microscope-based approach, the endoscopic approach provides better visualization, decreased invasiveness, and fewer complications, particularly for the removal of extrasellar and parasellar tumor extension [9, 14]. The EEEA provides the possibility to resect the tumor with suprasellar extension, but at the same time, causes additional bone resection and more trauma than the standard surgery. Youssef et al reported that EEEA was not applicable for the safe removal of PAs invading the cavernous sinus [19]. However, other studies using EEEA have reported a wider visualization and working space, enabling the resection of PAs located in the suprasellar regions, cavernous sinus, and clivus safely and effectively [18, 20, 21]. The EEEA always uses the binostril route, which requires at least two surgeons. Sheng Han et al argued that a mononostril technique was adequate for the endoscopic resection of most PAs with moderate extension [22]. However, Elhadi et al reported that the binostril approach provided better surgical freedom than the mononostril approach from a study of 8 silicon-injected cadaveric heads [23]. Guodao et al performed a systemic review and meta-analysis and found the binostril approach caused less pituitary disturbance and fewer hospitalization days, whereas the mononostril approach showed less trauma of the nasal cavity [24].

Our department started the transition from microscopic to endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery for PA from October 2013. In our experience, the application of EEEA to resect PA by a binostril, four-handed method is safe and effective. Although the standard transsphenoidal approach is adequate for the majority of PAs, the binostril approach has more extensive indications and benefits the management of bleeding complications during the procedure with more working space. This may be more important to giant adenoma and invasive adenoma. Generally, the standard transsphenoidal approach can resect microadenom well. But for the tumor located within pituitary, the EEEA can offer better visualization to find and resect the tumor.

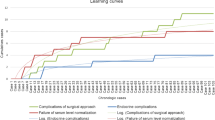

It is critical to understand there is a steep learning curve for EEEA. The surgeon must be skilled in the equipment used in this approach and become accustomed to the image distortion and the loss of stereoscopic vision. Recently, many clinical centers have used a three-dimensional (3D) endoscope view to improve the visualization of anatomical structures and their relationships. This 3D endoscope may reduce the learning curve of the surgeon, and provide stereoscopic vision and depth perception [25, 26].

GTR

The GTR rate of endoscopic surgery for PA varies widely from 62% to 94%, with most reports around 70% [14, 15, 27,28,29,30,31,32]. In our study, the assessment of resection was determined by the postoperative MR images, and GTR was achieved in 126 patients (73.68%), similar to that reported by other studies. About 25% patients had a subtotal or partial resection for the following reasons: huge size or tough texture of the tumor; rich blood supply; tumor was partitioned by septa; and parasellar and suprasellar extension. Jain et al reported that tumor size and volume, as well as parasellar and suprasellar extensions were associated with surgical outcome. They found that the favorable factors for total removal were a tumor volume less than 5 cm3 with no parasellar and suprasellar extension [33]. Qiuhang et al argued that soft lesions were better suited to an endoscopic approach than hard, solid tumors [34].

Total removal of all the PA is discouraged because it may increase the incidence of serious complications, especially for some tumors that have invaded the cavernous sinus or encased the internal carotid arteries (as shown in Fig. 3). Gondim et al reported a patient with a macroadenoma and right side hemiparesis presented in the first postoperative day, with a hematoma in the left side of the pons found by MRI. The patient recovered partially at 6 months after surgery, but still presenting with a mild weakness on the right side. The author believed this event might have been associated with the attempt to achieve a GTR of the retrosellar at the position of the lesion [29].

At the beginning of our learning curve, 2 patients had a second microscopic surgery to resect the residual tumor. The first was a 23-year-old man with a GH-secreting macroadenoma (length × width × height: 3.1 × 3.8 × 3.8 cm, volume: 22.3 cm3). The tumor had grown upwards and invaded the suprasellar region. We performed an endoscopic surgery to resect the lower section of the tumor and the residual section was resected by microscopic surgery 7 weeks later. This patient also underwent a gamma knife treatment 10 months after the first surgery and had an ideal outcome (Fig. 4). The other patient was a 46-year-old woman who had a nonfunctional giant adenoma (length × width × height: 2.7 × 5.8 × 5.3 cm, volume: 41.5 cm3). She underwent a similar treatment and recovered well. There were 2 patients who had a second endoscopic surgery, both of which had a tumor too big to resect totally from one surgery. The second surgeries were similar to the first, and they both recovered without problems. 11 patients in our series underwent a postoperative gamma knife treatment, which is a safe and effective treatment for PA [35, 36]. In our opinion, EEEA surgery and subsequent gamma knife treatment is a good way to treat tumors that are difficult to resect totally.

Coronal and sagittal MRI images of a patient who underwent a second surgery. a: MRI image before surgery, showing the anterior cranial base was invaded by the macroadenoma; b: MRI image after the first surgery when the tumor has been partly resected; c: MRI image after the second surgery, showing the tumor was subtotal removed

Complications

Postoperative CSF leak has always been an intractable problem of transsphenoidal surgery. In our study, postoperative CSF leak was observed in 3 patients (1.75%). Ciric et al reported that 3172 neurosurgeons were asked about the complications of transsphenoidal surgery by questionnaire and 985 reported they had performed transsphenoidal surgery. The neurosurgeons were divided based on the number of surgeries performed, <200, 200–500, and >500. The postoperative CSF leak index for these groups was 4.2%, 2.8%, and 1.5%, respectively [37]. Abtin tabaee et al conducted a meta-analysis of 821 patients who underwent an endoscopic approach, and showed the rate of CSF leak varied from 0%–27% [14]. Other published studies reported rates of CSF leak of 0.83%–10.3%, which are comparable with our study [29, 32, 38,39,40]. We believe the most important measure to avoid this complication is the adequate repair of the sella floor.

Diabetes insipidus is a common complication after PA surgery. In previous studies, the rate of temporary and permanent diabetes insipidus was 0–22% and 0–5%, respectively [14, 29, 32, 38,39,40]. There were 14 patients (8.19%) with temporary diabetes insipidus in our study, and no permanent diabetes insipidus cases were observed. Temporary diabetes insipidus may be a result of the temporary dysfunction of vasopressin-producing neurons caused by surgical trauma. This can be precluded by avoiding manipulation of the pituitary stalk [37].

The rate of other complications reported in our study including hypopituitarism, hyposmia or anosmia, cerebral hemorrhage and epistaxis, may decrease with an increase in surgeon experience of the transsphenoidal procedures; a gentle technique and careful dissection may be key to reducing such complications.

Death

There was one death in our series, a 50-year-old woman suffered from bilateral vision loss for 1 year. She had a nonfunctional macroadenoma and underwent an EEEA surgery. She became delirious 10 h after the surgery. A cranial CT was performed immediately and showed a giant hematoma in the sellar and suprasellar regions. Then the patient underwent an emergency bilateral ventricular drainage but it was not effective. Without any sign of improvement, her family gave approval to stop treatment 4 days later. The cause of the hematoma might have been deficient hemostasis during the operation. This was a painful lesson for us and promoted us to try our best to avoid any complications.

Conclusion

The application of EEEA for PA resection by a binostril, four-handed technique can provide wider visualization and working space, and reduce trauma and complications. It is a secure and effective surgical method that can be used for the majority of PAs.

Abbreviations

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- ACTH:

-

Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- CAC:

-

Catheter with aqueous capsule

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EEEA:

-

Extended endoscopic endonasal approach

- GH:

-

Growth hormone

- GTR:

-

Gross total resection

- LNC:

-

Left nasal cavity

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MT:

-

Middle turbinate

- NS:

-

Nasal septum

- PA:

-

Pituitary adenoma

- PRL:

-

Prolactin

- RNC:

-

Right nasal cavity

- SSO:

-

Sphenoid sinus ostium

- ST:

-

Superior turbinate

- TSH:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

References

Ezzat S, Asa SL, Couldwell WT, Barr CE, Dodge WE, Vance ML, McCutcheon IE. The prevalence of pituitary adenomas. Cancer. 2004;101(3):613–9.

Goel A, Nadkarni T, Muzumdar D, Desai K, Phalke U, Sharma P. Giant pituitary tumors: A study based on surgical treatment of 118 cases. Surg Neurol. 2004;61(5):436–46.

Kreutzer J, Fahlbusch R. Diagnosis and treatment of pituitary tumors. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17(6):693–703.

Wong A, Eloy JA, Couldwell WT, Liu JK. Update on prolactinomas. Part 2: Treatment and management strategies. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(10):1568–74.

Gillam MP, Molitch ME, Lombardi G, Colao A. Advances in the treatment of prolactinomas. Endocr Rev. 2006;27(5):485–534.

Horsley V. Remarks on ten consecutive cases of operations upon the brain and cranial cavity to illustrate the details and safety of the method employed. Br Med J. 1887;1(1373):863–5.

Schloffer H. Erfolgreiche operation eines hypophysentumors auf nasalem wege. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1907;20:621–4.

Hardy J. Transphenoidal microsurgery of the normal and pathological pituitary. Clin Neurosurg. 1969;16:185–217.

Singh H, Essayed WI, Cohen-Gadol A, Zada G, Schwartz TH. Resection of pituitary tumors: endoscopic versus microscopic. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2016;130:309-317.

Guiot J, Rougerie J, Fourestier M, Fournier A, Comoy C, Vulmiere J, Groux R. Intracranial endoscopic explorations. Presse Med. 1963;71:1225–8.

Jankowski R, Auque J, Simon C, Marchal JC, Hepner H, Wayoff M. Endoscopic pituitary tumor surgery. Laryngoscope. 1992;102(2):198–202.

Jho HD, Carrau RL. Endoscopy assisted transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma: Technical note. Acta Neurochir. 1996;138(12):1416–25.

Cappabianca P, Cavallo LM, Solari D, Stagno V, Esposito F, de Angelis M. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for pituitary adenomas. World Neurosurg. 2014;82 Suppl 6:S3–S11.

Tabaee A, Anand VK, Barrón Y, Hiltzik DH, Brown SM, Kacker A, Mazumdar M, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic pituitary surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):545–54.

Gao Y, Zhong C, Wang Y, Xu S, Guo Y, Dai C, Zheng Y, Wang Y, Luo Q, Jiang J. Endoscopic versus microscopic transsphenoidal pituitary adenoma surgery: a meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:94.

Oertel J, Gaab MR, Tschan CA, Linsler S. Mononostril endoscopic transsphenoidal approach to sellar and peri-sellar lesions: Personal experience and literature review. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29(4):532–7.

Couldwell WT, Weiss MH, Rabb C, Liu JK, Apfelbaum RI, Fukushima T. Variations on the standard transsphenoidal approach to the sellar region, with emphasis on the extended approaches and parasellar approaches: Surgical experience in 105 cases. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(3):539–47.

Zhao B, Wei YK, Li GL, Li YN, Yao Y, Kang J, Ma WB, Yang Y, Wang RZ. Extended transsphenoidal approach for pituitary adenomas invading the anterior cranial base, cavernous sinus, and clivus: a single-center experience with 126 consecutive cases Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2010;112(1):108–17.

Youssef AS, Agazzi S, van Loveren HR. Transcranial surgery for pituitary adenomas. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(1):168–75.

Cappabianca PMD, Cavallo LMMD, de Divitiis EMD. Endoscopic Endonasal Transsphenoidal Surgery. Neurosurgery. 2004;55(4):933–41.

Laufer I, Anand VK, Schwartz TH. Endoscopic, endonasal extended transsphenoidal, transplanum transtuberculum approach for resection of suprasellar lesions. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(3):400–6.

Han S, Ding X, Tie X, Liu Y, Xia J, Yan A, Wu A. Endoscopic endonasal trans-sphenoidal approach for pituitary adenomas: Is one nostril enough? Acta Neurochir. 2013;155(9):1601–9.

Elhadi AMMDP, Hardesty DAMD, Zaidi HAMD, Kalani MYSMDP, Nakaji PMD, White WLMD, Preul MCMD, Little ASMD. Evaluation of Surgical Freedom for Microscopic and Endoscopic Transsphenoidal Approaches to the Sella. Neurosurgery. 2015;11 Suppl 1:69–79.

Wen GD, Tang C, Zhong CY, Li X, Li JY, Li LW, Yang YQ, Ma CY. Mononostril versus binostril endoscopic transsphenoidal approach for pituitary adenomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos ONE. 2016;11(4):11.

Kari E, Oyesiku NM, Dadashev V, Wise SK. Comparison of traditional 2-dimensional endoscopic pituitary surgery with new 3-dimensional endoscopic technology: intraoperative and early postoperative factors. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2(1):2–8.

Pennacchietti V, Garzaro M, Grottoli S, Pacca P, Garbossa D, Ducati A, Zenga F. Three-dimensional endoscopic endonasal approach and outcomes in sellar lesions: a single-center experience of 104 cases. World Neurosurg. 2016;89:121–5.

Zhan R, Ma Z, Wang D, Li X. Pure endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal approach for nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas in the elderly: surgical outcomes and complications in 158 patients. World Neurosurg. 2015;84(6):1572–8.

O'Malley Jr BW, Grady MS, Gabel BC, Cohen MA, Heuer GG, Pisapia J, Bohman LE, Leibowitz JM. Comparison of endoscopic and microscopic removal of pituitary adenomas: single-surgeon experience and the learning curve. Neurosurg Focus. 2008;25(6):E10.

Gondim JA, Almeida JPC, Albuquerque LAF, Schops M, Gomes E, Ferraz T, Sobreira W, Kretzmann MT. Endoscopic endonasal approach for pituitary adenoma: surgical complications in 301 patients. Pituitary. 2011;14(2):174–83.

Bodhinayake I, Ottenhausen M, Mooney MA, Kesayabhotla K, Christos P, Schwarz JT, Boockyar JA. Results and risk factors for recurrence following endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for pituitary adenoma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;119:75–9.

Charalampaki P, Reisch R, Ayad A, Conrad J, Welschehold S, Perneczky A, Wüster C. Endoscopic endonasal pituitary surgery: surgical and outcome analysis of 50 cases. J Clin Neurosci. 2007;14(5):410–5.

Guvenc G, Kizmazoglu C, Pinar E, Imre A, Kaya I, Bezircioglu H, Yuceer N. Outcomes and complications of endoscopic versus microscopic transsphenoidal surgery in pituitary adenoma. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27(4):1015–20.

Jain AK, Gupta AK, Pathak A, Bhansali A, Bapuraj JR. Endonasal transsphenoidal pituitary surgery: is tumor volume a key factor in determining outcome? Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29(1):48–50.

Qiuhang ZMDP, Hongchuan GMDP, Feng KMDP, Ge CMDP, Jiantao LMDP, Mingchu LMDP, Yuhai BMDP, Feng LMDP. Resection of the intracavernous sinus tumors using a purely endoscopic endonasal approach. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(1):295–302.

Fu P, He YS, Cen YC, Huang Q, Guo KT, Zhao HY, Xiang W. Microneurosurgery and subsequent gamma knife radiosurgery for functioning pituitary macroadenomas or giant adenomas: one institution’s experience. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;145:8–13.

Cohen-Inbar O, Xu ZY, Schlesinger D, Vance ML, Sheehan JP. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for medically and surgically refractory prolactinomas: long-term results. Pituitary. 2015;18(6):820–30.

Ciric I, Ragin A, Baumgartner C, Pierce D. Complications of transsphenoidal surgery: results of a national survey, review of the literature, and personal experience. Neurosurgery. 1997;40(2):225–36.

Gondim JA, Schops M, de Almeida JPC, de Albuquerque LAF, Gomes E, Ferraz T, Barroso FAC. Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery: surgical results of 228 pituitary adenomas treated in a pituitary center. Pituitary. 2010;13(1):68–77.

Ammirati M, Wei L, Ciric I. Short-term outcome of endoscopic versus microscopic pituitary adenoma surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(8):843–9.

Gaillard S. The transition from microscopic to endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery in high-caseload neurosurgical centers: the experience of foch hospital. World Neurosurg. 2014;82 Suppl 6:S116–20.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Authors’ contributions

HZ conceived of the study, and participated in its design; XJ participated in the design of the study and performed the operations and helped to draft the manuscript; ZL drafed the manuscript and participated in the perform of statistical collection and analysis; XH participated in the perform of statistical collection and analysis; HW participated in the perform of the operations and helped to collect the data, all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All patients in our study consented to publish those data, and we can offer the copy of the form.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We have submitted our study plan to Medical Ethics Committee of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, they confirmed that the ethics approval was not necessary for a retrospective study which just used to medical research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, X., Liu, Z., Huang, X. et al. Extended endoscopic endonasal approach for pituitary adenoma: a single-center experience of 171 patients. Chin Neurosurg Jl 3, 18 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-017-0080-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41016-017-0080-9