Abstract

Background

To systematically review the literature for methods to localize the genial tubercle as a means for performing an advancement of the genioglossus muscle.

Methods

PubMed, Google Scholar, CRISP, EMBASE, CINAHL, and Scopus were searched from inception through June 16, 2015.

Results

One hundred fifty-two articles were screened, and the full text versions of 12 articles were reviewed in their entirety and 7 publications reporting their methodology for localizing the genial tubercle. Based upon these measurements and the results published from radiographic imaging and cadaveric dissections of all the papers included in this study, we identified the genial tubercle as being positioned within the mandible at a point 10 mm from the incisor apex and 10 mm from the lower mandibular border.

Conclusion

Based upon the results of this review, the genial tubercles were positioned within the mandible at a point 10 mm from the incisor apex and 10 mm from the lower mandible border. It may serve as an additional reference for localizing the genial tubercle and the attachment of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible, although the preoperative radiological evaluation and the palpation of the GT are recommended to accurately isolate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) poses a significant medical problem plaguing a diverse group of individuals within all demographics throughout the world. USA Today reports an increase in cases of OSA within the US Military community by 150% from 2009 to 2013. Genioglossus advancement (GA) surgery effectively addresses the problem of retrolingual airway narrowing with minimal surgical intervention. Many surgeons balk at this surgical modality due to difficulty in isolating the position of the genioglossus muscle and increased risk of devitalizing teeth. We present an additional reference to localize the genial tubercle for increasing ease of the genioglossus advancement procedure based on a systematic review of pertinent literature on this topic from1984 to 2013.

Per its definition, repetitive episodes of pharyngeal collapse with increased airflow resistance leads to obstructive sleep apnea. Treatment and management of OSA necessitates various medical and surgical interventions. Selection of the appropriate treatment modality relies significantly upon the degree and type of obstructive pathology [1,2,3,4]. Surgical alternatives remain reserved for treatment of the most severe forms of OSA and patients with poor compliance on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices [4, 5].

Among various surgical methods, genioglossus advancement provides an effective technique to resolve the obstructive pathology caused by retrolingual airway narrowing. Riley et al. first described the GA technique for the treatment of OSA in 1984 [6]. Since its inception, several studies validated the utility of this technique [7, 8]. When performed correctly, the patient enjoys distinct improvement in retrolingual airway patency. However, the key to ensuring success of this surgical treatment requires accurate assessment and localization of the attachment of the belly of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible to ensure maximal advancement of the genioglossus muscle [8].

In order to identify the position of the genioglossus muscle, the surgeon employs various methods to include manual palpation and more recently, cone beam computed tomography (CBCT). However, the surgeon typically encounters significant difficulty in accurately identifying the position of the genioglossus muscle and its point of attachment to the mandible. Consequently, in the absence of surgical dissection to directly visualize the actual bony attachment of the muscle, the GA technique requires some degree of “blind luck” in identifying the primary point of attachment of the belly of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible [6,7,8].

Realizing the importance of isolating and identifying the attachment of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible, we conducted an exhaustive systematic review of the literature from 1984 to 2013. These studies provided measurements correlated with cephalometrics identifying the position of the genioglossus muscle and its attachment to the mandible. From a systematic review of the measurements from these articles, we developed the Rule of Tens with respect to the genial tubercle in assisting the surgeon to more accurately localize the attachment of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible and further enhance efficacy of the GA surgical technique.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of all literature written in or translated into English from 1984 to March 2015 on the topic of Genioglossus Advancement. The search revealed articles with topics that included measurements collected from cadaveric and/or radiographic studies. MEDLINE served as the primary database of the majority of the literature search. In addition, each author also conducted individual searches on PubMed, CRISP, EMBASE, CINAHL and Scopus. The systematic search used the following search terms: “geniotomy” OR “genioglossus advancement” OR “genial tubercle” OR “genial tubercle advancement” OR “genioglossus muscle advancement” OR “GTA” OR “GGA” OR “inferior sagittal mandibular osteotomy” OR “mandibular osteotomy” OR “sliding genioplasty” AND “sleep.” The result of the literature search and review identified more than one hundred articles on these topics. Of these, seven articles met inclusion criteria as assessed by the authors (YDK, ETC and MC) who individually reviewed the abstracts of all searched articles for information pertinent to this systematic review.

Upon final review, the authors excluded two articles written in Chinese due to the absence of English translation for the remainder of the papers and possible discrepancy in content. One article in particular appeared to present pertinent information likely to contribute to this systematic review; however, the lack of English translation hindered an accurate review and assessment [9]. The authors included the remaining five articles following a comprehensive review of the entire text in English [10,11,12,13,14]. To further identify possible relevant articles, the authors reviewed the references cited in each individual article. The authors identified two potential papers. However, upon final evaluation, the authors excluded these identified articles due to age and lack of relevance [15, 16]. In addition, the authors of one paper adopted a conventional tomography technique which appeared to lack validity and fraught with inconsistent images [15].

Results

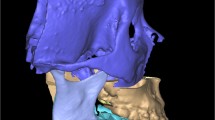

Figure 1, Table 1, and Table 2 provide a list of the selected and comprehensively reviewed articles. Two articles described cadaveric studies and one study provided a description based on a radiographic assessment. The remaining two articles presented validation studies comparing CT scans with the measurements obtained from cadaveric dissections. Due to the inherent heterogenicity among the identified references, direct comparisons of the pertinent measured anatomical landmarks and the specific measurement points remained difficult.

The majority of the reviewed literature provided a range for the genial tubercle height (GTH). The data from the radiographic measurements revealed a GTH from 5 to 8 mm. However, one cadaveric study refuted these findings somewhat due to a significant different result in their measurement range for the GTH [10]. Wang et al. [14] presented more detailed radiographic measurements according to the gender and dental occlusion. They measured the distance from the inferior border of the mandible (IBM) to the inferior border of genial tubercle (IGT) (IGT-IBM) as 6 to 11 mm. Of note, other studies measured this distance from the center of the genial tubercle.

Further, Wang et al. provided measurements for the distance from the apices of the lower incisors (LI) to the superior border of the genial tubercle (SGT) (LI-SGT) as 8 to 15 mm. They measured the GTH as 5 to 11 mm, genial tubercle width (GTW) as 5 to 8 mm, and the thickness of the anterior mandible (MT) as 11 to 14 mm. Based upon these measurements and the results published from radiographic imaging and cadaveric dissections of all the papers included in this study, we identified the GT as positioned within the mandible at a point 10 mm from the incisor apex and 10 mm from the lower mandible border. However, due to the individual anatomical variations of the chin, the height of the GT cannot be concluded with the position. Therefore, localization of the GT for attachment of the bellies of the genioglossus muscle should be preoperatively evaluated using imaging modalities.

Discussion

Since the introduction of the GA procedure for OSA patients as an effective method of mandibular inferior border osteotomy for genioglossus advancement [6, 7], surgeons attempted other variations on this technique to improve efficacy. Currently, the most widely utilized technique employs the formation of a rectangular osteotomy within the mandible. When performed correctly, the GA surgical procedure addresses the retrolingual obstruction and significantly improves patency of the airway [5,6,7,8].

The success or failure of the GA technique relies prominently in accurately identifying the attachment of the belly of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible. From anatomical studies based on cadaveric dissections and radiographic imaging, the skeletal attachment of the genioglossus muscle appears localized about the genial tubercle. As with many anatomical structures, some degree of variation exists among the patient population.

Moreover, the accurate location of the muscle attachment remains difficult to confirm even intraoperatively causing some degree of consternation to the novice surgeon. Though the genioglossus muscle and genial tubercle area are palpable by means of digital pressure on the anterior mouth floor area, the spatial information and relationship to other anatomical structures remain elusive to the surgeon with limited experience in performing this procedure. Due to this inherent uncertainty and difficulty in localizing the attachment of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible, several groups attempted cadaveric studies to more clearly delineate the skeletal attachment [10, 12, 13].

Other groups augmented these findings with radiographic imaging modalities. Though more practical, imaging based on X-ray radiography presents some limitations on accurately identifying soft tissue structures. Consequently, two studies attempted to validate the radiographic evaluations by comparing cadaveric measurements to those obtained from CT scans [11, 13].

Because OSA typically presents with greater prevalence in skeletal occlusion class II patients with a posteriorly displaced and small chin, the dimension and the location of the genial tubercle appears more important for optimizing the assessment and plan for treatment. One radiographic study using CBCT compared the measurements based on the skeletal pattern and genders [14]. This group’s results revealed that the IGT-IMB (distance from the mandibular inferior border to the inferior margin of genial tubercle) of skeletal class II males was significantly different when compared to that of the skeletal class I female. However, they concluded that no significant differences existed among the skeletal patterns and genders even with the noted difference in IGT-IMB.

As for the dimensional difference between males and females in the context of the local anatomy for genioglossus advancement, most of the literature provided no specificity of the gender of their respective subjects. They did, however, present the distances between the superior border of the genial tubercle and the apex of the lower incisor separately with respect to the gender of the subject [13]. Use of three-dimensional CBCT scans improves visualization of the local anatomy. However, X-ray radiography remains limited in its ability to identify soft tissue morphology. Subsequently, accurate identification of the attachment of the belly of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible during genioglossus advancement remains difficult. Through experience and development of knowledge regarding spatial anatomy, the surgeon gains more expertise in more accurately performing the GA technique.

Previous cadaveric studies provided clear visualization of the genioglossus muscle and its subsequent attachments to the mandible. These studies helped to elucidate a relationship with these attachments to the position of the genial tubercle. To augment this estimation of muscle attachment, imaging modalities rely heavily upon X-ray radiography. Further, in order to validate radiographic studies of the lingual topography of the anterior mandible, some researchers correlated the cadaveric dissection with CT scans. These measurements vary among studies. We reviewed these anatomic and radiographic studies and compared the measurements from each study. From this systematic review, manual palpation to identify genial tubercle might be important; however, with the progress of digital technology and three-dimensional imaging techniques, we can definitely take advantage of the virtual surgery system to capture the genial tubercle [17]. Therefore, based on this observation, individual planning should be considered when genioglossus advancement is planned.

Conclusion

Based upon the results of this review, the genial tubercles were positioned within the mandible at a point 10 mm from the incisor apex and 10 mm from the lower mandible border. It may serve as an additional reference for localizing the genial tubercle and the attachment of the genioglossus muscle to the mandible, although the preoperative radiologic evaluation and individualized computer-assisted surgery can be further utilized.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- CBCT:

-

Cone beam computed tomography

- CPAP:

-

Continuous positive airway pressure

- GA:

-

Genioglossus advancement

- GTH:

-

Genial tubercle height

- GTW:

-

Genial tubercle width

- IBM:

-

Inferior border of the mandible

- IGT:

-

Inferior border of genial tubercle

- LI:

-

Lower incisors

- MT:

-

Thickness of the anterior mandible

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- SGT:

-

Superior border of the genial tubercle

References

Goncalves MA, Paiva T, Ramos E, Guilleminault C (2004) Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, sleepiness, and quality of life. Chest 125(6):2091–2096

Berry RB, Harding SM (2004) Sleep and medical disorders. Med Clin North Am 88(3):679–703 ix

Randerath WJ, Verbraecken J, Andreas S, Bettega G, Boudewyns A, Hamans E et al (2011) Non-CPAP therapies in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J 37(5):1000–1028

Ephros HD, Madani M, Yalamanchili SC (2010) Surgical treatment of snoring & obstructive sleep apnoea. Indian J Med Res:131267–131276

Senders CW, Strong EB (2003) The surgical treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 25(3):213–220

Riley R, Guilleminault C, Powell N, Derman S (1984) Mandibular osteotomy and hyoid bone advancement for obstructive sleep apnea: a case report. Sleep 7(1):79–82

Li KK, Riley RW, Powell NB, Troell RJ (2001) Obstructive sleep apnea surgery: genioglossus advancement revisited. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 59(10):1181–1184 discussion 1185

Lewis MR, Ducic Y (2003) Genioglossus muscle advancement with the genioglossus bone advancement technique for base of tongue obstruction. J Otolaryngol 32(3):168–173

Yi H, Yin S, Guan J, Lu W, Yu D, Huang Y (2004) Applied anatomic study for genioglossus advancement. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Ke Za Zhi 18(12):719–722

Hennessee J, Miller FR (2005) Anatomic analysis of the genial bone advancement trephine system’s effectiveness at capturing the genial tubercle and its muscular attachments. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133(2):229–233

Hueman EM, Noujeim ME, Langlais RP, Prihoda TJ, Miller FR (2007) Accuracy of cone beam computed tomography in determining the location of the genial tubercle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 137(1):115–118

Silverstein K, Costello BJ, Giannakpoulos H, Hendler B (2000) Genioglossus muscle attachments: an anatomic analysis and the implications for genioglossus advancement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 90(6):686–688

Yin SK, Yi HL, Lu WY, Guan J, Wu HM, Cao ZY et al (2007) Anatomic and spiral computed tomographic study of the genial tubercles for genioglossus advancement. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 136(4):632–637

Wang YC, Liao YF, Li HY, Chen YR (2012) Genial tubercle position and dimensions by cone-beam computerized tomography in a Taiwanese sample. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 113(6):e46–e50

Krekmanov L, Andersson L, Ringqvist M, Wilhelmsson B, Walker-Engstrom ML, Tegelberg A et al (1998) Anterior-inferior mandibular osteotomy in treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg 13(4):289–298

Mintz SM, Ettinger AC, Geist JR, Geist RY (1995) Anatomic relationship of the genial tubercles to the dentition as determined by cross-sectional tomography. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53(11):1324–1326

Lee JW, Lee DW, Ohe JY, Kwon YD (2017) Accurate genial tubercle capturing method using computer-assisted virtual surgery for genioglossus advancement. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 55(1):92–93

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EC wrote the manuscript. YK conceived the study idea and wrote the manuscript. JJ edited the manuscript. RC conceived the idea of the study and gave advices to the work. RR conceived the idea and gave advices. SL edited the manuscript. MC collected literatures and conceived the idea of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, E.T., Kwon, YD., Jung, J. et al. Genial tubercle position and genioglossus advancement in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treatment: a systematic review. Maxillofac Plast Reconstr Surg 41, 34 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0217-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-019-0217-1