Abstract

Genome-resolved metagenomic sequencing approaches have led to a substantial increase in the recognized diversity of microorganisms; this included the discovery of novel metabolic pathways in previously recognized clades, and has enabled a more accurate determination of the extant distribution of key metabolisms and how they evolved over Earth history. Here, we present metagenome-assembled genomes of members of the Chloroflexota (formerly Chloroflexi or Green Nonsulfur Bacteria) order Aggregatilineales (formerly SBR1031 or Thermofonsia) discovered from sequencing of thick and expansive microbial mats present in an intertidal lagoon on Little Ambergris Cay in the Turks and Caicos Islands. These taxa included multiple new lineages of Type 2 reaction center-containing phototrophs that were not closely related to previously described phototrophic Chloroflexota—revealing a rich and intricate history of horizontal gene transfer and the evolution of phototrophy and other core metabolic pathways within this widespread phylum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Most of the known diversity of phototrophic Chloroflexota (formerly Chloroflexi or Green Nonsulfur Bacteria) was derived from isolation- and sequencing-based efforts primarily on hot spring microbial mats (e.g. [35, 42]). However microbial communities with diverse members of phototrophic Chloroflexota are commonly found in other environments, including coastal marine environments and carbonate platforms (e.g. [36]). While cultivation-based efforts have yet to isolate phototrophic Chloroflexota from outside of the Chloroflexia class in pure culture [35], genome-resolved metagenomic sequencing has made substantial progress in uncovering novel diversity of phototrophic lineages that have otherwise remained inaccessible and unknown (e.g. [6, 19, 42, 48]).

The Turks and Caicos Islands occur at the southern end of the Bahamian archipelago. The Caicos platform (Fig. 1) is a contiguous shallow (< 5 m), grainy carbonate platform situated in the trade winds (mean wind velocity of 8 m/s from the east), and has a dry climate with net evaporation in excess of precipitation [10]. We studied microbial mats found throughout Little Ambergris Cay—a small ~ 6 km-long uninhabited island near the southern margin of the platform. Little Ambergris Cay contains a bedrock rim, formed by amalgamated cemented beach ridges and fossil eolian dunes, enclosing a tidal lagoon with a dozen large cut channels that communicate between the lagoon with well-mixed platformal waters. The typical diurnal tidal range is ~ 0.3 m. Polygonal microbial mats occur within the lagoon amongst sparse black mangroves. These mats are inundated daily by high tides. The mats are dissected into individual decimeter-sized heads that take on an upward domed shape by mature polygons with 60° angles created by episodic desiccation. On average twice a decade, tropical storms transport ooid sediment forming across the platform into the lagoon and onto the mats [37]—creating a mode of lamination in addition to that created by microbial succession. Dominant mat building taxa are a thickly-sheathed, heterocystous cyanobacterium of the genus Scytonema and the thin-walled cyanobacterium, Halomicronema [36]. The mats host a rich sulfur cycling community (Gomes et al.: Microbial mats on Little Ambergris Cay, Turks and Caicos Islands: taphonomy and the selective preservation of biosignatures/submitted). Deeper layers of the mat contain abundant purple/red- and green- colored microbes visible in exposed cross sections of the mats (Fig. 1); these have been confirmed by 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing to include diverse and abundant phototrophs in the Proteobacteria and Chloroflexota phyla [36].

Geological context of the microbial mats from which the genomes in this study were recovered. a location of the Turks and Caicos Islands. b location of Little Ambergris Cay. c microbial mats and mangroves in tidal flat. d cross section of microbial mat showing pigmented layers containing phototrophic bacteria

In order to better characterize the diversity and evolutionary histories of phototrophic Chloroflexota, we recovered five metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from genome-resolved metagenomic sequencing of microbial mats from the Turks and Caicos Islands which include novel phototrophic lineages of Chloroflexota not closely related to previously described phototrophs.

Methods

Methods for metagenomic sequencing and genome binning followed those published previously [45, 46] and described briefly here. Samples of microbial mat were collected using an ethanol-sterilized spatula (~ 0.25 cm3 of material per sample). Immediately after sampling, cells were lysed and DNA preserved with a Zymo Terralyzer BashingBead Matrix and Xpedition Lysis Buffer. Lysis was achieved by attaching tubes to the blade of a cordless reciprocating saw (Black & Decker, Towson, MD) and operating for 1 min. Following return to the lab, bulk environmental DNA was extracted and purified with a Zymo Soil/Fecal DNA extraction kit. Purified DNA was submitted to SeqMatic LLC (Fremont, CA) for library preparation and sequencing via Illumina NextSeq.

Raw sequence reads from four samples were co-assembled with MegaHit v. 1.02 [22] and genome bins constructed based on nucleotide composition and differential coverage using MetaBAT [18], MaxBin [50], and CONCOCT [1] prior to dereplication and refinement with DAS Tool [32] to produce the final bin set. Annotation was performed using RAST [2]. Genome completeness and redundancy/contamination was estimated with CheckM [28], and likelihood of presence or absence of metabolic pathways was estimated with MetaPOAP [43]. Visualization of the presence of annotated metabolic pathways was done via KEGG-decoder [13] following annotation of proteins sequences by GhostKOALA [17]. Taxonomic assignments were verified with GTDB-Tk [8, 29].

Protein sequences used in analyses (see below) were identified locally with the tblastn function of BLAST + [7], aligned with MUSCLE [11], and manually curated in Jalview [49]. Positive BLAST hits were considered to be full length (e.g. > 90% the shortest reference sequence from an isolate genome) with e-values better than 1e− 20. Phylogenetic trees were calculated using RAxML [33] on the Cipres science gateway [25]. Transfer bootstrap support values were calculated by BOOSTER [20], and trees were visualized with the Interactive Tree of Life viewer [21]. Concatenated ribosomal protein alignments were built following methods from Hug et al. [16]. Evolutionary histories of vertical versus horizontal inheritance of metabolic genes were inferred by comparison of the topologies of organismal and metabolic protein phylogenies [9, 42, 47, 48].

Results

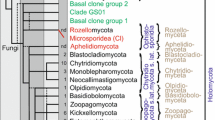

Illumina NextSeq sequencing of four samples from the Turks and Caicos Islands produced a total of 243,782,642 reads of 151 nucleotides. These were coassembled into 3,464,316 contigs totaling 2,510,159,592 nucleotides. Binning of this dataset produced five medium- to high-quality genomes (according to accepted quality standards, [5]) which could be taxonomically classified by GTDB-Tk into the lineage of the Chloroflexota phylum currently annotated as order SBR1031 (Table 1, Fig. 2). Other genomes previously assigned to this clade included those proposed as the class Candidatus Thermofonsia [42] along with an isolate for which the order Aggregatilineales was recently proposed [26]. Following the isolation and characterization of Aggregatilinea lenta [26], and the clustering of these organisms into an order-level clade by GTDB-Tk, we propose the reassignment of the organisms previously described as “Candidatus Thermofonsia” into the order Aggregatilineales. This order is primarily made up of nonphototrophic organisms but also contains some members with full suites of phototrophy genes, which appear to have been derived via horizontal gene transfer from members of the Chloroflexia class of Chloroflexota [42].

a Concatenated ribosomal protein phylogeny of the Chloroflexota, focusing on order SBR1031 (Aggregatilineales). Organisms encoding phototrophy with a Type 2 reaction center highlighted in green (including TC_22, which did not recover reaction center genes but may be a phototroph, as discussed in the text). Genomes first described here noted with pink circles. As species names are not available for MAGs of uncultured organisms, strains are labelled with MAG IDs (this study) or NCBI WGS database IDs (others) followed by taxonomy as derived from GTDB-Tk. Clades not the focus of this study have been collapsed and labeled with GTDB-Tk taxonomy. b Tanglegram showing phylogenetic (in)congruence between concatenated ribosomal proteins (left) reflecting organismal relationships with PufM (right) as a marker of the horizontal gene transfer of phototrophy proteins. Dotted lines show topological congruence within some lineages of Chloroflexia (in black) and incongruence between Roseiflexus, Roseilinea, and phototrophic members of SBR1031 (in red). This is indicative of horizontal gene transfer of phototrophy proteins from the Roseiflexus lineage to Roseilinea and SBR1031

Discussion

The environmental range exhibited by known members of the SBR1031/Aggregatilineales was previously somewhat limited. Previously recovered genomes of members of this group were sourced from hot spring environments [42, 46], with the single known isolate isolated from subseafloor sediments [26]. 16S rRNA sequences of SBR1031 have been recovered from more diverse environments including hot springs [39, 40], contaminated soils [24], and wastewater [3]. Recovery of MAGs belonging to this order from carbonate tidal flats therefore expands the available genomic diversity and known range of Aggregatilineales to environments that also have an extensive geological record.

The SBR1031 MAGs reported here encoded similar sets of functional genes to previously reported members of this order (Fig. 3). Like previously described members of SBR1031/Aggegatilineales (e.g. [42]), these organisms encode aerobic respiration via an A-family heme copper O2 reductase, and contain both a bc complex and an alternative complex III [42]; based on these electron transport chain complexes, it is likely that these organisms are at least facultatively aerobic. All genomes described here (except for TC_22, the least complete genome) also encode a bd oxidase (O2 reductase) capable of functioning for O2 detoxification or respiration at low O2 concentrations [4]—a trait observed in both aerobic and anaerobic members of the Anaerolineae class (e.g. [14, 27, 38, 42]).

Heatmap of metabolic functions of Aggregatilineales genomes produced by KEGG-decoder. The color gradient reflects the fractional abundance of genes associated with a pathway encoded by a particular genome (i.e. white encodes 0 genes, and darkest red encodes all genes annotated as part of the pathway). Genome IDs as used in this study (TC##) or as WGS identifiers (all others). Note that the apparent presence of Calvin cycle genes in TC_22 and other members of Aggregatilineales is due to the presence of a Form IV rubisco-like protein that does not catalyze CO2 fixation, as described in the text

Of the five SBR1031/Aggregatilineales genomes reported here, three encode partial or full components necessary for phototrophic energy transduction via a Type 2 reaction center. TC_71 and TC_152 encode complete sets of marker genes for phototrophy, including those encoding PufL and PufM subunits of the reaction center and bacteriochlorophyll synthesis (e.g. BchX, BchY, and BchZ). MetaPOAP False Positive estimates for phototrophy in these organisms were low (< 0.04), suggesting that it is very unlikely that these genes were recovered as a result of contamination in the MAGs. The TC_22 genome encodes the BchXYZ complex but did not recover genes for PufL or PufM; MetaPOAP False Positive and False Negative estimates were similarly low (~ 0.04) for this genome, and based on this analysis it remains unclear whether or not this organism contains a complete set of genes for phototrophy. However, the gene cluster encoding BchX, BchY, and BchZ in TC_22 is located on the end of a contig, and the region of the chromosome syntenous to that encoding PufL and PufM in other phototrophic Chloroflexota (e.g. 6.5 kb upstream of bchX, bchY, and bchZ in TC_152) is missing in the TC_22 genome. Based on this, it is possible that this organism hosts a complete phototrophy pathway but that some genes simply were not recovered in the MAG. Like previously described phototrophs in SBR1031, these organisms do not encode a BchLNB complex or the capacity for carbon fixation via either the 3-hydroxypropionate bi-cycle or the Calvin cycle [42]. It is worth noting, however, that TC_22 does encode a Form IV rubisco-like protein on a small contig; however enzymes in this family are not capable of catalyzing CO2 fixation and instead are used for a variety of other functions [34] and this genome does not encode phosphoribulose kinase.

Comparisons of organismal (based on concatenated ribosomal proteins and other vertically inherited markers) and phototrophy protein (e.g. PufL, PufM) phylogenies indicated substantial incongruences between organismal and phototrophy tree topologies. These relationships are indicative of a history of horizontal gene transfer (Fig. 2b) (e.g. [30]). In particular, the reaction centers found in members of SBR1031 branch with those of Roseiflexus rather than as a clade separate from those of Chloroflexia (e.g. Chloroflexus + Roseiflexus), suggesting that horizontal transfer of phototrophy proteins occurred from the Roseiflexus branch to members of SBR1031—a pattern previously recognized in other members of the SBR1031/Aggegatilineales [42]. Interestingly, like Roseiflexus and some other phototrophic members of SBR1031/Aggegatilineales [42], TC_71 and TC_152 encode fused pufL/pufM genes encoding the two subunits of the Type 2 reaction center heterodimer. Together with reaction center protein phylogenic relationships, this observation indicated that the reaction centers of these organisms are more closely related to those of the Roseiflexus lineage of Chloroflexia than to the more closely related Ca. Roseilinea gracile, which encodes unfused pufL and pufM genes. A corollary of these observations of is that phototrophy in SBR1031 must postdate the acquisition and diversification of phototrophy in the Chloroflexia, events that have been estimated to have occurred in the last ~ 1 billion years [31].

Conclusions

While horizontal gene transfer can be confidently determined to have been responsible for the presence of phototrophy in SBR1031, it remains unclear to what extent intra-order horizontal gene transfer played a role in the extant distribution of phototrophy within the clade. Phototrophic lineages of SBR1031 show a polyphyletic distribution, separated by many nonphototrophic lineages (Fig. 2a). This distribution could be reasonably explained by the presence of phototrophy in the last common ancestor of SBR1031 followed by extensive loss in most lineages; however differences in the topology of phototrophy proteins and organismal phylogenies within SBR1031 may indicate later acquisition followed by multiple instances of horizontal gene transfer between members of the clade. Discovery and study of additional phototrophic members of SBR1031 will be valuable to confidently resolve phylogenetic relationships of SBR1031 phototrophy proteins to assess organismal relationships in this clade.

The expanded environmental distribution and genetic diversity of Chloroflexota phototrophs described here further reinforces that genome-resolved metagenomic sequencing can provide an effective avenue for discovering novel microbial diversity, particularly of hard-to-culture phototrophs (e.g. [6, 15, 35, 41, 48]). These data also reinforce hypotheses that horizontal gene transfer has been a major mechanism behind the extant distribution of anoxygenic phototrophy (e.g. [12, 42, 48]). Together with the mounting evidence that most microbial lineages that have ever lived are now extinct [23], the continuing lack of discovery of donor lineages for horizontal gene transfer of phototrophy leads toward a consistent hypothesis: most phototrophic lineages that have ever existed have gone extinct, but relatively frequent horizontal gene transfer has allowed phototrophy pathways to persist in new lineages (e.g. [44]).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI WGS repository under project ID PRJNA602167 with Accession IDs of JAADYW-JAADYZ.

References

Alneberg J, Bjarnason BS, de Bruijn I, Schirmer M, Quick J, Ijaz UZ, Loman NJ, Andersson AF, Quince C. CONCOCT: clustering contigs on coverage and composition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.4038; 2013.

Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics. 2008;9(1):75.

Björnsson L, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW, Blackall LL. Filamentous Chloroflexi (green non-sulfur bacteria) are abundant in wastewater treatment processes with biological nutrient removal. Microbiol. 2002;148(8):2309–18.

Borisov VB, Gennis RB, Hemp J, Verkhovsky MI. The cytochrome bd respiratory oxygen reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1398–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.016.

Bowers RM, Kyrpides NC, Stepanauskas R, Harmon-Smith M, Doud D, Reddy TBK, Schulz F, Jarett J, Rivers AR, Eloe-Fadrosh EA, Tringe SG. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35(8):725–31.

Bryant DA, et al. Candidatus Chloracidobacterium thermophilum: an aerobic phototrophic acidobacterium. Science. 2007;317:523–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1143236.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. BLAST+: architecture and applications. Bmc Bioinform. 2009;10:421. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-421.

Chaumeil PA, Mussig AJ, Hugenholtz P, Parks DH. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(6):1925–7.

Doolittle RF. Of urfs and orfs: a primer on how to analyze derived amino acid sequences. Mill Valley: California, University Science Books; 1986.

Dravis JJ, Wanless HR. Caicos platform models of Quaternary carbonate deposition controlled by stronger easterly Trade Winds—application to petroleum exploration. In: Proceedings Developing models and analogs for isolated carbonate platform—Holocene and Pleistocene carbonates of Caicos Platform, British West Indies, vol. 22; 2008. SEPM, SEPM Core Workshop.

Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh340.

Fischer WW, Hemp J, Johnson JE. Evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2016;44:647–83.

Graham ED, Heidelberg JF, Tully BJ. Potential for primary productivity in a globally-distributed bacterial phototroph. ISME J. 2018;350:1–6.

Hemp J, Ward LM, Pace LA, Fischer WW. Draft genome sequence of Levilinea saccharolytica KIBI-1, a member of the Chloroflexi class Anaerolineae. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e01357–15. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.01357-15.

Holland-Moritz H, Stuart J, Lewis LR, Miller S, Mack MC, McDaniel SF, Fierer N. Novel bacterial lineages associated with boreal moss species. Environ Microbiol. 2018;20(7):2625–38.

Hug LA, Baker BJ, Anantharaman K, Brown CT, Probst AJ, Castelle CJ, Butterfield CN, Hernsdorf AW, Amano Y, Ise K, Suzuki Y. A new view of the tree of life. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1(5):16048.

Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:726–31.

Kang DD, Froula J, Egan R, Wang Z. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ. 2015;3:e165.

Klatt CG, et al. Community ecology of hot spring cyanobacterial mats: predominant populations and their functional potential. ISME J. 2011;5:1262–78. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.73.

Lemoine F, Domelevo Entfellner JB, Wilkinson E, Correia D, Davila Felipe M, De Oliveira T, Gascuel O. Renewing Felsenstein's phylogenetic bootstrap in the era of big data. Nature. 2018;556(7702):452–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0043-0.

Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W242–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw290.

Li D, Liu CM, Luo R, Sadakane K, Lam TW. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(10):1674–6.

Louca S, Shih PM, Pennell MW, Fischer WW, Parfrey LW, Doebeli M. Bacterial diversification through geological time. Nat Ecol Evol. 2018;2(9):1458.

Militon C, Boucher D, Vachelard C, Perchet G, Barra V, Troquet J, Peyretaillade E, Peyret P. Bacterial community changes during bioremediation of aliphatic hydrocarbon-contaminated soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2010;74(3):669–81.

Miller, M. A., W. Pfeiffer and T. Schwartz (2010). Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE).

Nakahara N, Nobu MK, Takaki Y, Miyazaki M, Tasumi E, Sakai S, Ogawara M, Yoshida N, Tamaki H, Yamanaka Y, Katayama A. Aggregatilinea lenta gen. Nov., sp. nov., a slow-growing, facultatively anaerobic bacterium isolated from subseafloor sediment, and proposal of the new order Aggregatilineales Ord. Nov. within the class Anaerolineae of the phylum Chloroflexi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2019;69(4):1185–94.

Pace LA, Hemp J, Ward LM, Fischer WW. Draft genome of Thermanaerothrix daxensis GNS-1, a thermophilic facultative anaerobe from the Chloroflexi class Anaerolineae. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e01354–15. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.01354-15.

Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25(7):1043–55.

Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Waite DW, Rinke C, Skarshewski A, Chaumeil PA, Hugenholtz P. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36(10):996–1004..

Raymond J, Zhaxybayeva O, Gogarten JP, Gerdes SY, Blankenship RE. Whole-genome analysis of photosynthetic prokaryotes. Science. 2002;298(5598):1616–20.

Shih PM, Ward LM, Fischer WW. Evolution of the 3-hydroxypropionate bicycle and recent transfer of anoxygenic photosynthesis into the Chloroflexi. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(40):10749–54.

Sieber CM, Probst AJ, Sharrar A, Thomas BC, Hess M, Tringe SG, Banfield JF. Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(7):836–43.

Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033.

Tabita FR, Satagopan S, Hanson TE, Kreel NE, Scott SS. Distinct form I, II, III, and IV Rubisco proteins from the three kingdoms of life provide clues about Rubisco evolution and structure/function relationships. J Exp Bot. 2008;59(7):1515–24.

Thiel V, Tank M, Bryant DA. Diversity of chlorophototrophic bacteria revealed in the omics era. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2018;69:21–49.

Trembath-Reichert E, Ward LM, Slotznick SP, Bachtel SL, Kerans C, Grotzinger JP, Fischer WW. Gene sequencing-based analysis of microbial-mat morphotypes, Caicos platform, British West Indies. J Sediment Res. 2016;86(6):629–36.

Trower EJ, O’Reilly SS, Gomes M, Cantine M, Stein N, Grotzinger H, Strauss JV, Lamb MP, Grotzinger JP, Knoll AH, Fischer WW. Active ooid growth driven by sediment transport in a high energy shoal, Little Ambergris Cay, Turks and Caicos, British Overseas Territories. J Sedimentary Res. 2018;88:1132–51.

Ward LM, Hemp J, Pace LA, Fischer WW. Draft genome sequence of Leptolinea tardivitalis YMTK-2, a mesophilic anaerobe from the Chloroflexi class Anaerolineae. Genome Announc. 2015;3:e01356–15. https://doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.01356-15.

Ward LM. Microbial evolution and the rise of oxygen: the roles of contingency and context in shaping the biosphere through time (Doctoral dissertation, California Institute of Technology); 2017.

Ward LM, Idei A, Terajima S, Kakegawa T, Fischer WW, McGlynn SE. Microbial diversity and iron oxidation at Okuoku-hachikurou Onsen, a Japanese hot spring analog of Precambrian iron formations. Geobiology. 2017;15(6):817–35.

Ward LM, McGlynn SE, Fischer WW. Draft genome sequence of Chloracidobacterium sp. CP2_5A, a phototrophic member of the phylum Acidobacteria recovered from a Japanese hot spring. Genome Announc. 2017;5(40):e00821–17.

Ward LM, Hemp J, Shih PM, McGlynn SE, Fischer WW. Evolution of phototrophy in the Chloroflexi phylum driven by horizontal gene transfer. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:260.

Ward LM, Shih PM, Fischer WW. MetaPOAP: presence or absence of metabolic pathways in metagenome-assembled genomes. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(24):4284–6.

Ward LM, Shih PM. The evolution of carbon fixation pathways in response to changes in oxygen concentration over geological time. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;140:188–99.

Ward LM, Shih PM, Hemp J, Kakegawa T, Fischer WW, McGlynn SE. Genomic evidence for phototrophic oxidation of small alkanes in a member of the Chloroflexi phylum. bioRxiv. 2019:531582.

Ward LM, Idei A, Nakagawa M, Ueno Y, Fischer WW, McGlynn SE. Geochemical and metagenomic characterization of Jinata Onsen, a Proterozoic-analog hot spring, reveals novel microbial diversity including iron-tolerant phototrophs and thermophilic lithotrophs. Microbes Environ. 2019;34(3):278–92.

Ward LM, Johnston D, Shih PM. Phanerozoic radiation of ammonia oxidizing bacteria. bioRxiv. 2019:655399.

Ward LM, Cardona T, Holland-Moritz H. Evolutionary implications of anoxygenic hototrophy in the bacterial phylum Candidatus Eremiobacterota (WPS-2). Front Microbiol. 2019d;10:1658. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01658.

Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DMA, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview version 2-a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(9):1189–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033.

Wu YW, Tang YH, Tringe SG, Simmons BA, Singer SW. MaxBin: an automated binning method to recover individual genomes from metagenomes using an expectation-maximization algorithm. Microbiome. 2014;2(1):26.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was made possible with support from the Agouron Institute, NSF IOS project # 1833247, and the Caltech Center for Environment-Microbe Interactions. LMW acknowledges support from an Agouron Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship and the Simons Foundation Collaboration on Marine Microbial Ecology. UFL was supported by an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UFL, JPG, and WWF performed field work and collected samples. UFL and LMW processed and analyzed data. LMW wrote the manuscript with assistance from UFL, JPG, and WWF. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ward, L.M., Lingappa, U.F., Grotzinger, J.P. et al. Microbial mats in the Turks and Caicos Islands reveal diversity and evolution of phototrophy in the Chloroflexota order Aggregatilineales. Environmental Microbiome 15, 9 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-020-00357-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-020-00357-8