Abstract

Background

Soft tissue reconstruction is typically conducted after evacuation from theater of operations. If circumstances do not allow timely evacuation, however, defect site may need to be reconstructed in the combat zone.

Case presentation

A total of 41 patients with extremity soft tissue defect were treated using pedicled flaps by a single orthopedic surgeon during four deployments in Chad, Afghanistan and Mali between 2010 and 2017. The mean age was 25.6 years. A total of 46 injury sites in extremities required flap coverage: 19 combat-related injuries (CRIs) and 27 non-combat related injuries (NCRIs). Twenty of the injury sites were infected. Overall, 63 pedicled flap transfers were carried out: 15 muscle flaps, 35 local fasciocutaneous flaps and 13 distant fasciocutaneous flaps. The flap types used did not differ for CRIs or NCRIs. Mean follow-up was 71 days. Complications included deep infection (n = 6), flap failure (n = 1) and partial flap necrosis (n = 1). Limb salvage rate was 92.7% (38/41).

Conclusions

Soft tissue defect can be managed with simple pedicled flaps in theatre of operations if needed. Basic reconstructive procedures should be part of the training for military orthopedic surgeons.

Trial registration

Retrospectively registered in January 2019 (2019-0901-001).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Modern conflicts present military surgeons with a high volume of extremity injuries requiring flap coverage [1]. Various studies have evaluated soft tissue coverage outcomes in U.S. military personnel after evacuation from combat zones [1, 2]. These reconstructive procedures performed in specialized centers by multidisciplinary teams are rarely accessible to local, national conflicts since they cannot be evacuated from the theater of combat [3].

Due to the lack of plastic surgeons in the battlefield, orthopedic surgeons often find themselves alone when managing local patients who present with complex extremity injuries requiring multi-tissue reconstruction. In this austere environment, they routinely perform soft tissue coverage procedures using “simple, reliable and replicable” techniques [4,5,6].

In this case series, we report the use of pedicled flap transfers in combat zone medical treatment facilities (MTFs).

Case presentation

Data collection and analysis

A total of 41 patients with extremity soft tissue defects were treated using pedicled flaps by a single orthopedic surgeon (LM) between 2010 and 2017 during four deployments as a member of forward surgical teams (FST) in Chad and Mali, and in a combat support hospital (CSH) in Afghanistan. Three types of pedicled flaps were used: muscle flaps, local fasciocutaneous flaps, and distant (fascio) cutaneous flaps.

Postoperative complications are presented using the Clavien-Dindo classification [7]. Outcome measures included flap loss, partial flap necrosis and early infections. Flap loss was defined as a need for coverage-revision surgery. Partial flap necrosis was defined as necrosis that necessitated surgical debridement but did not require additional coverage surgery. Early infections were defined as a wound infection at the coverage site within 2 weeks of flap transfer that required a return to the operating theater. Time to additional skin grafting on muscle flaps or the donor sites of fasciocutaneous flaps was also analyzed.

Endpoint assessment included limb/finger salvage and late complications due to infection. Injuries were categorized based on energy trauma and wound contamination to combat-related injuries (CRIs) versus non-combat related injuries (NCRIs). Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Baseline characteristics

The study included 41 subjects (35 male and 6 female patients, with a mean age of 25.6 ± 15.0 years). The origin of the injuries was non-ballistic trauma in 18 cases, ballistic trauma in 15 cases, osteomyelitis in 6 cases and burn in 2 cases. CRIs occurred significantly more frequently in Afghanistan than Chad and Mali (13/15 versus 2/15, P = 0.001). Four patients presented with multiple lesions. Thus, a total of 46 injury sites (19 CRIs and 27 NCRIs) required flap reconstruction. Most injuries were located in the legs (n = 23) or hands (n = 15), and with open fractures ((n = 27, Table 1). Twenty of the 46 injury sites were infected.

Pattern analysis of flap surgery

The average number of debridement procedures per injury was 1.8 ± 0.9. Serial debridement was required prior to flap coverage in 29 injuries; negative wound pressure therapy was used between debridement sessions in 12 injuries. Primary debridement and flap coverage were carried out simultaneously in 17 injuries.

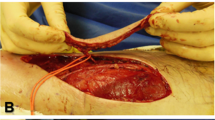

Two locoregional flaps were combined in 10 large defects, and 9 simultaneous distant abdominal flaps were required to cover a burn injury of both hands in a single patient. Thus, a total of 63 pedicled flap transfers were performed: 15 muscle flaps, 35 local fasciocutaneous flaps and 13 distant fasciocutaneous flaps. The flap types chosen for treatment did not differ between CRIs and NCRIs. Muscle flaps were mostly used for proximal and mid-tibia coverage; distal tibia coverage was achieved by transposition and island fasciocutaneous flaps (Fig. 1). Three thumb reconstructions were carried out using island digital flaps. Distant flaps were exclusively used for hand and forearm coverage (Fig. 2). Additional skin grafting was required in 40 of the 63 flap transfers and performed after a mean delay of 5 ± 5 days. Associated procedures included external fixation (n = 21), internal fixation (n = 11), bone reconstruction using the induced membrane technique (n = 10) and tendon repair (n = 3). Secondary division of the distant flap pedicle was carried out after three weeks.

Treatment outcome

The mean follow-up time was 71 ± 95 days. There were nine type III Clavien-Dindo complications: one abdominal flap loss, one partial necrosis of a groin flap (Fig. 2a), one knee joint-fluid fistula (Fig. 1a) and six early infections. All other complications were type I: two minimal marginal losses of fasciocutaneous flaps and one dehiscence at the donor site of a groin flap.

Three patients in Mali were offered a late amputation due to severe persistent infection; one of them declined below knee amputation for septic non-union of the tibia as he was able to walk on crutches without pain. Three patients had a chronic pus-fistula under their muscle flap reconstruction related to tibia infection: two had been treated for a neglected open fracture and one for severe osteomyelitis. Limb salvage rate was 92.7% (38/41).

Discussion

Battlefield MTFs provide life- and limb-saving care through damage-control surgical procedures. The conditions in the field are typically ill-suited to support specialized plastic surgery. Therefore, studies reporting the results of flap reconstruction in theatres of operations are rare. Barbier et al. [5] analyzed the use of muscle and rotational fasciocutaneous flaps for recent, or neglected, open-tibia fractures, septic non-unions, and osteomyelitis. We have also previously reported a series of 35 pedicled flap transfers for soft tissue reconstruction of various CRIs in Afghanistan [4]. Klem et al. [3] reported on a case series of microsurgical free-flap procedures, performed by plastic or ear, nose and throat surgeons together with orthopedic surgeons, in U.S. CSHs that were deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan.

To our knowledge, this is the first published case series of soft tissue coverage by a single surgeon over multiple tours of duty in various locations. In our opinion, this feature reduces the impact of confounding factors on the results (inter-surgeon variability) and enhances the applicability of the results across multiple types of theater of operations.

In modern reconstructive units within well-provisioned healthcare facilities, soft tissue reconstruction is individually tailored to the wound, available and reliable flap sources, associated injuries and specific rehabilitation goals for each patient [1]. In battlefield MTF environment, however, the choices for soft tissue coverage methods are restricted. Factors that affect treatment decisions include the surgeon’s expertise and available resources (e.g., surgical equipment, antibiotics, laboratory analysis facilities and the number of available beds) [4]. For these reasons, the simplest solution for coverage is always preferred [4, 6]. In our experience, pedicled flaps combined with skin grafts allowed reconstruction of almost all types soft tissue extremity injuries, even large ones. Additional skin grafts were carried out together with flap transfers in most patients but were deferred in cases at risk of early infection. Simultaneous local, or distant, pedicled flaps were used successfully in this cohort as an alternative to free transfers [4, 6]. This decision was based on our limited experience with such procedures, as well as the following 2 considerations. First, free flaps require microsurgical techniques and specific post-operative care, and thus could hardly be carried out by non-specialized healthcare teams. Second, free flap surgery requires an extended period in theater that can jeopardize the operational activity of a forward surgical facility [4].

In the present study, the failure rate was low for both CRIs and NCRIs. The overall success rate for flap coverage performed in the field was over 90%, a figure comparable to various other authors’ reports about war-related extremity reconstructions performed in patients after evacuation out of the combat zone [1, 2]. In our opinion, the relatively high success rate could be attributed to the near-exclusive use of simple, reliable, and replicable pedicled flap transfers, which were perfectly suited to both CRIs and NCRIs in a non-specialist surgical MTF [4,5,6]. Transposition, or rotational, fasciocutaneous flaps and muscle flaps were the two types most often used, regardless of the injury location or cause. Since these flaps do not require pedicle dissection, the procedure could be readily performed by surgeons with no specialized training in plastic surgery.

Other flap types (e.g., perforator and distant flaps) were also used in this study. Perforator flaps are not recommended for CRI treatment due to the extensive soft tissue injury and the potential violation of fascial planes and perforators caused by the projectile’s kinetic energy [2]. They were mostly employed to treat NCRIs; they were dissected as island flaps with a large adipofascial pedicle (designed with a ratio L/l < 4) following Doppler examination. When using such flaps, non-specialized surgeon should be aware that the flap design is based on the location of the vascular territory of the perforator as well as the perforator flow direction [8]. Propeller perforator flaps were never used because they were too technically demanding [9]. Distant flaps were indicated to salvage upper limbs, mostly at the hand level, even though they required a minimum 3-week hospital stay. By contrast, we did not use cross-leg flaps for tibia coverage as our experience has led us to conclude that an amputation should be considered in absence of available local flaps in such austere healthcare settings [6].

There were 12 flap complications, half of which were due to early infections, highlighting the importance of infection control in both CRIs and NCRIs. Regardless of the method of soft tissue reconstruction, adequate debridement of necrotic or infected tissue is critical for the overall success of any reconstructive modality [2, 6]. Highly contaminated war wounds usually require serial debridement and broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics prior to definitive coverage [2]. Management of NCRIs, such as neglected open fractures, septic non-unions, and chronic osteomyelitis, also follow the same therapeutic rules. Within the limitations of MTF conditions, therefore, treatment of bone infections should be undertaken with caution if extended courses of antibiotics, sequential procedures, and close monitoring (for several months) will not be possible [4, 6].

The current study demonstrated that an orthopedic surgeon with basic knowledge in local vascular anatomy is able to harvest an appropriate local, regional or distant pedicle flap to manage the majority of soft tissue defects in the field. A supplemental training in reconstructive techniques would, however, be required for deployed orthopedic surgeons who are not familiar with extremity reconstruction. In the French Military Health Service such training is now included in the Advanced Course for Deployment Surgery [10]. During the training, basic pedicled flap transfers and bone reconstruction techniques that can be performed in healthcare facilities with limited resources are learned through lectures, hands-on exercises on cadavers and case studies [6].

This study has several limitations. First, the study population was heterogeneous in terms of factors like injury mechanism and the time elapsed before management. Second, indications for the different pedicle flaps are open for discussion as they reflected only the views and experience of one surgeon. Third, the short follow-up made it impossible to evaluate long-term limb salvage, bone infection control and achievement of bone union.

Conclusions

Pedicled flap transfers are safe and useful procedures suitable for soft tissue coverage within forward surgical units. All military orthopedic surgeons should be trained to perform such basic reconstruction techniques. Except perhaps in cases of pre-existing bone infection, these techniques permit limb salvage in most open extremity soft tissue injuries encountered in the field.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

21 January 2021

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via the original article.

Abbreviations

- CRI:

-

Combat related injury

- CSH:

-

Combat support hospital

- FST:

-

Forward surgical team

- MTF:

-

Medical treatment facility

- NCRI:

-

Non-combat related injury

References

Sabino J, Polfer E, Tintle S, Jessie E, Fleming M, Martin B, et al. A decade of conflict: flap coverage options in traumatic war-related extremity reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(3):895–902.

Connolly M, Ibrahim ZR, Johnson ON. Changing paradigms in lower extremity reconstruction in war-related injuries. Mil Med Res. 2016;3:9.

Klem C, Sniezek JC, Moore B, Davis MR, Coppit G, Schmalbach C. Microvascular reconstructive surgery in operations Iraqi and enduring freedom: the US military experience performing free flaps in a combat zone. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(2 Suppl 2):S228–32.

Mathieu L, Gaillard C, Pellet N, Bertani A, Rigal S, Rongiéras F. Soft-tissue coverage of war extremity injuries: the use of pedicle flap transfers in a combat support hospital. Int Orthop. 2014;38(10):2175–81.

Barbier O, Ollat D, Pasquier P, Rigal S, Versier G. Could the orthopaedic surgeon deployed in auster setting perform flaps on the leg? Acta Orthop Belg. 2017;83(1):35–9.

Mathieu L, Potier L, Niang CD, Rongiéras F, Duhamel P, Bey E. Type III open tibia fractures in low resources setting. Part 2: soft-tissue coverage with simple, reliable and replicable pedicle flaps. Med Sante Trop. 2018;28(3):230–6.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey N, Dindo D, Schulick RD, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–96.

Saint-Cyr M, Wong C, Schaverien M, Moiallal A, Rohrich RJ. The perforasome theory: vascular anatomy and clinical implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(5):1529–44.

Sisti A, D’Aniello C, Fortezza L, Tassinari J, Cuomo R, Grimaldi L, et al. Propeller flaps: a literature review. In Vivo. 2016;30(4):351–73.

Bonnet S, Gonzalez F, Mathieu L, Boddaert G, Hornez E, Bertani A, et al. The French Advanced Course for Deployment Surgery (ACDS) called Cours Avancé de Chirurgie en Mission Extérieure (CACHIRMEX): history of its development and future prospects. J R Army Med Corps. 2016;162(5):343–7.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Jennifer Dandrea Palethorpe for assistance in preparing this manuscript, and to all medical and paramedical staff of the various MTFs who took part in the treatment of the patients.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LM, JCM and CG have operated on the patients. LM, SP and NdE have analyzed and interpreted the patient data. AB and FR participated in critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients gave oral consent to participate in this case study. This study was approved by the Department of Surgery of the French Military Health Service Academy (2019-0901-001).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mathieu, L., Plang, S., de l’Escalopier, N. et al. Soft tissue coverage using pedicled flap in combat zone: a case series. Military Med Res 7, 51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-020-00281-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-020-00281-5