Abstract

Background

This study assessed the relationship between insertion torque and bone quality evaluated during surgery and in preoperative computed tomographic (CT) images analyzed either visually or by rescaled mean gray values (MGVs). The study also tested the correlation between the clinical and radiographic measures of bone quality.

Methods

The consecutive sample was composed of 45 short implants (4.1 × 6 mm) placed in the posterior region of 20 patients. Intra-surgical tactile bone quality, based on the classification of bone types by Lekholm and Zarb, and insertion torque were recorded during the implant placement. Visual bone quality and normalized MGV were assessed in standardized axial, coronal, and sagittal sections of preoperative CT images. Data were analyzed by ANOVA and Spearman correlation (alpha = 0.05).

Results

Insertion torque was associated with all assessment methods of bone quality (tactile, CT visual, MGV). A moderate correlation was found among all methods of bone quality, except for CT visual assessment and tactile evaluation. MGVs varied as a function of arch, dental region, insertion torque, and bone types.

Conclusions

The results suggest that bone quality measures affect primary stability as recorded by insertion torque, and the assessment methods are consistently related.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The early clinical success of short implants can be affected by poor bone quality and low primary stability because implant micromovement can promote the formation of a fibrous capsule during the osseointegration process. It has been reported that the greater the insertion torque, the greater the resistance of the bone-implant interface to the shear forces that tend to rotate the implant [1]. Clinically, insertion torque is the most practical method for measuring primary stability and can be recorded with the manual torque wrench or contra-angle and motor used for implant placement. Resonance frequency and damping capacity have also been used to measure the primary and secondary stability of short implants in research [2], but the procedures are more complex and require sophisticated equipment and extra clinical time.

Bone quality is a generic term for the characterization of bone tissue in three dimensions: the structural quality, related to the amount of the cortical bone and to the trabecular bone pattern; the bone density, related to the amount of bone mineralization and/or the amount of bone by its volume; and the amount of bone, related to the volume of bone available [3]. Bone quality varies intra- and inter-subject depending on the thickness of cortical bone, the amount of trabecular bone, and the amount of bone tissue mineralization in the region of interest for implant placement [4]. Some classifications of bone quality have considered cortical bone thickness and trabecular bone structure based on preoperative panoramic radiographs and tactile perception during exploratory drilling of the implant site; bone density based on the tactile sensation and Hounsfield units of computed tomography (CT) images; radiographic pattern of trabecular bone; and intra-surgical bone density and biopsy with histomorphometric evaluation [5,6,7,8]. However, most classifications of bone quality for routine clinical use still are not validated by using objective and subjective assessment methods.

Both multislice CT and cone beam CT are used for presurgical assessment of bone density and quality [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. There is a strong correlation between gray values in cone beam CT and Hounsfield units in multislice CT [4, 12,13,14]. The visual inspection of CT sections avoids the superimposition of anatomical structures seen in radiographs; thus, the region of interest in trabecular bone can be evaluated without the interference of cortical bone. Positive associations of primary stability with bone density [15], bone volume [16], and thickness of the cortical bone [17] have been reported. If it were possible to accurately relate bone quality measures with primary implant stability, the surgical, prosthetic, and loading planning could be more precise and predictable.

Therefore, this study aimed at assessing the relationship between insertion torque and bone quality evaluated by intra-surgical tactile perception and in preoperative CT images analyzed either visually or by rescaled mean gray values. The association among the subjective and objective measures of bone quality also was tested. The null hypothesis is that there is no relation between insertion torque, visual, and rescaled gray values of the bone in this sample of short implants.

Methods

This study reports cross-sectional, correlational data of a prospective clinical research project [2] approved by the university Institutional Review Board (10/05074). The research protocol followed the precepts of the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All patients signed an informed consent form.

A consecutive, non-probabilistic sample consisted of 45 implants placed in 20 patients treated by experienced specialists in oral implantology in a private clinic setting. Inclusion criteria were adult patients in need for implant-supported single crowns in the posterior region of the maxilla and mandible and indication of 6-mm long implants, with 2 mm of safety margins for the mandibular canal, lingual cortex of submandibular fossa, and maxillary sinus. Patients were excluded according to the following criteria: previous osseointegration failure or pathologic lesions in the region of interest, use of bone graft or biomaterials, use of bisphosphonates, heavy smoking habit (up to 10 cigarettes/day), non-controlled diabetes, immunosuppression, local radiotherapy, active periodontal disease, poor oral hygiene, or use of removable prosthesis in the antagonist arch.

Clinical data were collected by means of anamnesis, physical examination, and preoperative CT images for surgical planning. Data on implant characteristics and insertion torque were collected at the surgery session.

Surgical protocol and insertion torque measurement

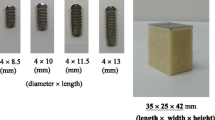

A total of 45 Standard Plus Regular Neck SLActive® implants (Straumann AG, Basel, Switzerland), 6-mm long and 4.1-mm diameter, were installed in 20 patients. The non-submerged, one-stage surgical protocol was adopted.

Preoperative asepsis of the face and oral cavity was performed with 0.12% chlorhexidine. After local anesthesia with 4% articaine hydrochloride with adrenaline 1:100,000, an incision was made on the ridge crest with total detachment of the flap.

With a 16:1 counter-angle (KaVo Dental®, Biberach, Germany) coupled on an electric motor (Smart® Driller, Jaguaré, São Paulo, Brazil), at a rotation speed of 900 rpm, the surgical milling sequence (1.4-mm spherical drill, 2.3-mm spherical drill, 2.2-mm helical drill, 2.8-mm helical drill, and 3.5-mm helical drill) was performed, with no use of a countersink drill or bone tap. The implant was inserted to the limit between the treated surface of the threads and the smooth platform surface, by using the contra-angle with adapter, at a speed of 18 rpm (Fig. 1a).

The insertion torque was measured using the manual torque wrench (Straumann Dental Implant System®, Waldenburg, Switzerland) (Fig. 1b), according to three categories: < 15 N cm, 15 to 35 N cm, and > 35 N cm. A healing cap was installed, and the suture was made with nylon 5-0 (Fig. 1c). The patients were prescribed with antibiotics (amoxicillin 500 mg, 8/8 h for 7 days), anti-inflammatory drugs (nimesulide 100 mg, 12/12 h for 4 days), and mouthwash with 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate for 15 days. The sutures were removed after 1 week.

Intra-surgical tactile evaluation of bone quality (bone types)

During the drilling for implant placement, the surgeon used his tactile perception to assess the bone ridge. The surgeon considered the thickness of the cortical layer and the resistance of the trabecular bone to categorize the bone into four types, based on the classification of Lekholm and Zarb [5]: type 1 (large homogeneous cortical bone and little trabecular bone), type 2 (thick cortical layer surrounding a dense trabecular bone), type 3 (thin cortical layer surrounding a dense trabecular bone), and type 4 (thin cortical layer surrounding a sparse trabecular bone). All surgeries were performed by the same previously trained surgical team.

Preoperative computed tomography images

Preoperative diagnostic CT images were acquired in the Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) protocol, and one single cone beam scanner (i-CAT, Imaging Sciences Intl, Hatfield, PA, USA) and one single multislice scanner (Elscint CT Twin II, Elscint Ltd., Haifa, Israel) were used in this study. The DICOM images were reconstructed with the ImageJ software (version 1.51; National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) for bone quality evaluation of the regions of interest (ROIs).

A standardized digital periapical radiograph was obtained after suture removal and used to measure the distance from the actual implant center to the proximal side of the nearest tooth at bone level. Using this reference distance, the ROIs in the 1-mm thick CT slices were manually traced corresponding to the alveolar bone (cortical and trabecular bones) in the axial, coronal, and sagittal sections as follows (Fig. 2):

-

Axial ROI: Using the reference implant location line, the ROI was defined as the alveolar bone area with a 6-mm width corresponding to 3 mm on each side of the future implant center, including the buccal and lingual cortical layers.

-

Coronal ROI: Area defined by the outer border of the cortical bone with a 6-mm height and a line joining the buccal and lingual cortical layers.

-

Sagittal ROI: A 6 × 6 mm square was defined as the area corresponding to the implant plus 1 mm of the surrounding bone at the mesial and distal sides.

Visual assessment of bone quality (bone types)

The visual evaluation of bone quality in the preoperative CT images was performed by a senior, calibrated, and experienced radiologist in CT, who was blind to the other measures of bone quality and insertion torque. After memorizing the ROIs traced in the axial, coronal, and sagittal CT sections, the boundary lines were removed to avoid any interference during the visual assessment. The cortical bone was defined as a white and homogeneous outer layer of the alveolar ridge. The trabecular bone was defined as the structure between the two cortical layers. The examiner analyzed the images as many times as needed to categorize each implant site into bone types 1, 2, 3, or 4, according to the classification of Lekholm and Zarb [5].

Measurement of mean gray values

The DICOM files were imported to the ImageJ software, and the original axial stacks were used for CT image normalization in 32-bit [18]. Two 5 × 5 mm squares were delimitated for air and soft tissue in the same axial slice containing the ROI (cortical plus trabecular bones).

The original CT scans were rescaled applying the following formula:

where −GVair is the mean gray value for air and GVst is the mean gray value for a central soft tissue square. This calibration was performed by subtracting the gray value for air and multiplying the result by the ratio of 1000 divided by the result of the gray value for soft tissue minus the gray value for air. As a result of this gray value transformation, GVair = 0 and GVst = 1000 for all CT images.

The mean gray value of each rescaled ROI was measured on the three orthogonal planes: axial, coronal, and sagittal, totaling three ROIs per implant site. The average of the rescaled gray values for the three ROIs was computed for each implant site.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by descriptive and inferential statistics using the software XLSTAT version 2018 (Addinsoft SARL, New York, USA), and a two-tailed significance level of 0.05 was adopted. Spearman correlation coefficients were used to test the association among assessment methods of bone quality (intra-surgical tactile evaluation, CT visual assessment, mean gray values) and primary stability (insertion torque). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD was used to test the variation of mean gray values (average of ROIs) as a function of arch (maxilla, mandible), dental region (premolar, molar), insertion torque (< 15 N cm, 15 to 35 N cm, > 35 N cm), and bone types (1, 2, 3, 4) as classified by CT visual assessment and by intra-surgical tactile evaluation.

Results

Descriptive statistics of the sample are shown in Table 1. For statistical analysis, some data were missing: one implant had mobility after surgery and was lost and four CT scans, containing 11 ROIs, were not used for bone quality analysis due to technical problems. As only one case was categorized as bone type 1 by CT visual or by tactile evaluation, the corresponding mean gray values were excluded for the ANOVA tests. Shapiro-Wilk tests showed that the data on mean gray values for all three ROIs and average values followed normal distributions.

Table 2 shows that insertion torque had significant correlation with all assessment methods of bone quality. A moderate association was found among all methods to assess bone quality, except for CT visual and intra-surgical tactile evaluation.

There was a significant difference in rescaled mean gray values (average) as a function of arch (mandible greater than maxilla), dental region (premolar greater than molar), insertion torque (greater in higher torque, > 35 N cm, than in low torques, < 15 N cm), and bone quality (type) as categorized by tactile evaluation (bone types 2 and 3 greater than type 4) and CT visual assessment (bone type 2 greater than types 3 and 4) (Table 3).

Discussion

This study showed that low bone quality, as assessed by clinical and image methods, is related with low primary stability of 6-mm short implants placed at the posterior region of the maxilla and mandible. Higher insertion torque values were associated with better bone types and higher mean gray values in CT images. Insertion torque had a negative moderate association with bone type categorization by intra-surgical tactile evaluation and visual assessment of CT images. In addition, a positive moderate association was found between insertion torque and average mean gray values, as well as for segmental mean gray values in the axial, coronal, and sagittal ROIs.

The present study assessed the variation in normalized mean gray values to evaluate the bone quality in preoperative CT images using the axial, coronal, and sagittal sections, and the average of the three ROIs. Several studies have investigated the potential clinical application of CBCT mean gray values, especially for bone density evaluation in comparison with various clinical bone parameters [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. However, before using CBCT gray values for bone density estimations, a histogram calibration is needed.

One single cone beam scanner (i-CAT, Imaging Sciences Intl, Hatfield, PA, USA) and one single multislice scanner (Elscint CT Twin II, Elscint Ltd., Haifa, Israel) were used in this study. Even though quantitative differences in absolute numbers might be expected using distinct imaging modalities, a clinical approach was established to clinically comparable values. Using rescaled gray values through a pseudo-Hounsfield scale, the small differences between them were minimized.

In addition to the known CBCT exposure factors that contribute to the deviation of gray values, e.g., noise, beam hardening, limited FOV, local tomography effect, and the position inside the FOV, the machines appear to have incorporated a “histogram shift” in their reconstruction algorithm. This implies that the gray values are distributed based on the contents of the scan. The contrast of each individual scan is optimized, but gray values differ between scans containing low- or high-density materials. The presence of high-density objects in the scan shifts the histogram, leading to lower gray values throughout the image [28]. Previous studies tried to correct the inconsistency and calibrate gray values along a Hounsfield unit or a density scale [13, 28,29,30].

In this study, low- and medium-density values (air and a central FOV soft tissue) were used as reference calibration points for image normalization. The use of a reference object in the FOV containing at least two materials of known density could allow for a calibration similar to the use of reference phantoms in quantitative CT, rather than the “standard” automatic normalization function available in image analysis software that uses the lowest and highest gray values as calibration points. Although some differences in the rescaled values still exist because of differences in kilovoltage and filtration, they do provide a more meaningful result than the original gray values. Thus, rescaling might allow the comparison of densities from different patients, which would otherwise not be possible.

The average mean gray values were higher in the mandible than in the maxilla, like previously reported by González-Garcia and Monje [31], and premolar region and molar region, respectively, indicating anatomical differences for bone density. In comparison with insertion torque, the average mean gray values were different between the extreme categories of < 15 N cm and > 35 N cm, but not with the intermediate insertion torque. Although there was a consistent numerical decrease in absolute values, mean gray values were only statistically different for bone type 4 as classified by the subjective intra-surgical tactile evaluation. Bone types 2 and 3 were not discriminatory, which suggests inter-variability in these categories. One possible explanation is that the classification of bone quality was firstly determined by the tactile perception of the cortical bone thickness during the surgical perforation. A thick cortical layer would categorize the bone into types 1 or 2 according to the widely used classification by Lekholm and Zarb [5], even if the trabecular bone was not dense. One possible missing category would be a bone type with thick cortical layer and sparse trabecular bone, which could have intermediate characteristics and behavior between the types of thick and thin cortical bones (Fig. 3). This may be particularly important for short implants because the ROI, to determine the mean gray values and surgical perforation, had 6 mm in depth. Thus, the presence of a less-dense trabecular bone in some of the sites classified as bone type 2 may possibly have decreased the mean gray values. Fuster-Torres et al. [23] found significant differences between the maxilla and the mandible in mean bone density using Hounsfield unit (HU) in CBCT, with a mean torque insertion of 42.4 + − 4 N cm, with no differences for insertion torque (IT) between the posterior maxilla and mandibular implants, with very low bone density vs IT correlation coefficients. This could be related to the gray values (GV) inconsistency without GV calibration and using HU in CBCT. Comparisons between the present study and Fuster-Torres et al.’s study are not possible due to several method differences, including the use of HU in CBCT and different implant geometry, which alone is not adequate.

The present study also used the same preoperative CT images for visual evaluation of bone quality at the exact implant site, using the axial, coronal, and sagittal sections in a standardized procedure. There was a fairly moderate correlation between CT visual assessment and mean gray values, but no statistical difference was found in average mean gray values between the visual classification of bone types 3 and 4. One likely explanation is that the visual assessment is highly subjective to analyze bone structure and density in contrast to the objective quantification of minor changes in gray values invisible to the naked eye of the most experienced imaging specialist. The preoperative identification of bone type 4 implies greater surgical care and a certain risk for the prosthetic treatment. In these cases, possible clinical procedures include sub-drilling and bicortical anchoring, submerged, two-stage protocol, avoiding immediate or early loading, and using implants with surface treatment.

One limitation of the present study is the restriction to a single implant system and measurements and the relative small sample size, which decreased the power of analysis within the subgroups of bone types, although statistically significant results were found. Nevertheless, this study introduces a standardized method to assess bone quality in the exact implant site, using pre-surgical CT images in the axial, coronal, and sagittal sections. Further research is warranted to test the assessment methods in larger and diverse samples and to develop other three-dimensional analytical protocols in preoperative CT images for a possible “virtual biopsy” of the implant site.

Conclusions

In summary, within the conditions and limitations of this study, the results suggest that bone quality has a significant effect on the primary stability of short implants as measured by insertion torque. Insertion torque had significant correlation with all assessment methods of bone quality. For preoperative CT evaluation of bone quality, mean gray values (optical density) had stronger association with insertion torque than subjective visual assessment. Therefore, preoperative quantification of bone quality with good correlation with surgery outcome measures could save clinical time and improve implant treatment planning.

Abbreviations

- CBCT:

-

Cone beam computed tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomographic

- DICOM:

-

Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine

- FOV:

-

Field of view

- MGVs:

-

Mean gray values

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

References

Degidi M, Daprile G, Piattelli A. Determination of primary stability: a comparison of the surgeon’s perception and objective measurements. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2010;25:558–61.

Alonso FR, Triches DF, Mezzomo LAM, Teixeira ER, Shinkai RSA. Primary and secondary stability of single short implants. J Craniofac Surg. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000004567.

Ribeiro-Rotta RF, Lindh C, Pereira AC, Rohlin M. Ambiguity in bone tissue characteristics as presented in studies on dental implant planning and placement: a systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2011;22:789–801.

Valiyaparambil JV, Yamany I, Ortiz D, Shafer DM, Pendrys D, Freilich M, et al. Bone quality evaluation: comparison of cone beam computed tomography and subjective surgical assessment. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2012;27:1271–7.

Lekholm U, Zarb GA. Patient selection and preparation. In: Branemark PI, Zarb GA, Albektsson T, editors. Tissue integrated prostheses: osseointegration in clinical dentistry. Chicago: Quintessence; 1985. p. 199–209.

Misch CE. Density of bone: effect on treatment plans, surgical approach, healing, and progressive boen loading. Int J Oral Implantol. 1990;6:23–31.

Lindh C, Petersson A, Rohlin M. Assessment of the trabecular pattern before endosseous implant treatment: diagnostic outcome of periapical radiography in the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:335–43.

Trisi P, Rao W. Bone classification: clinical histomorphometric comparison. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1999;10:1–7.

Turkyilmaz I, Ozan O, Yilmaz B, Ersoy AE. Determination of bone quality of 372 implant recipient sites using Hounsfield unit from computerized tomography: a clinical study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2008;10:238–44.

Isoda K, Ayukawa Y, Tsukiyama Y, Sogo M, Matsushita Y, Koyano K. Relationship between the bone density estimated by cone-beam computed tomography and the primary stability of dental implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:832–6.

Arisan V, Karabuda ZC, Avsever H, Özdemir T. Conventional multi-slice computed tomography (CT) and cone-beam CT (CBCT) for computer-assisted implant placement. Part I: relationship of radiographic gray density and implant stability. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2013;15:893–906. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1708-8208.2011.00436.x.

Nomura Y, Watanabe H, Honda E, Kurabayashi T. Reliability of voxel values from cone-beam computed tomography for dental use in evaluating bone mineral density. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:558–62.

Reeves TE, Mah P, McDavid WD. Deriving Hounsfield units using gray levels in cone beam CT: a clinical application. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41:500–8.

Cassetta M, Stefanelli LV, Pacifici A, Pacifici L, Barbato E. How accurate is CBCT in measuring bone density? A comparative CBCT-CT in vitro study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2014;16:471–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/cid.12027.

Marquezan M, Osório A, Sant’Anna E, Souza MM, Maia L. Does bone mineral density influence the primary stability of dental implants? A systematic review. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23:767–74.

Makary C, Rebaudi A, Mokbel N, Naaman N. Peak insertion torque correlated to histologically and clinically evaluated bone density. Implant Dent. 2011;20:182–91.

Merheb J, Van Assche N, Coucke W, Jacobs R, Naert I, Quirynen M. Relationship between cortical bone thickness or computerized tomography-derived bone density values and implant stability. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21:612–7.

Miura K, editor. Bioimage data analysis. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2016. p. 293.

Barone A, Covani U, Cornelini R, Gherlone E. Radiographic bone density around immediately loaded oral implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:610–5.

Aranyarachkul P, Caruso J, Gantes B, Schulz E, Riggs M, Dus I, et al. Bone density assessments of dental implant sites: 2. Quantitative cone-beam computerized tomography. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2005;20:416–24.

Lee S, Gantes B, Riggs M, Crigger M. Bone density assessments of dental implant sites: 3. Bone quality evaluation during osteotomy and implant placement. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2007;22:208–12.

Song YD, Jun SH, Kwon JJ. Correlation between bone quality evaluated by cone-beam computerized tomography and implant primary stability. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24:59–64.

Fuster-Torres MA, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Peñarrocha-Oltra D. Relationships between bone density values from cone beam computed tomography, maximum insertion torque, and resonance frequency analysis at implant placement: a pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2011;26:1051–6.

Kaya S, Yavuz I, Uysal I, Akkus Z. Measuring bone density in healing periapical lesions by using cone beam computed tomography: a clinical investigation. J Endod. 2012;38:28–31.

Brosh T, Yekaterina BE, Pilo R, Shpack N, Geron S. Can cone beam CT predict the hardness of interradicular cortical bone? Head Face Med. 2014;10:12.

Tatli U, Salimov F, Kürkcü M, Akoğlan M, Kurtoğlu C. Does cone beam computed tomography-derived bone density give predictable data about stability changes of immediately loaded implants?: a 1-year resonance frequency follow-up study. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:e293–9.

Sennerby L, Andersson P, Pagliani L, Giani C, Moretti G, Molinari M, et al. Evaluation of a novel cone beam computed tomography scanner for bone density examinations in pre-operative 3D reconstructions and correlation with primary implant stability. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2015;17:844–53.

Pauwels R, Nackaerts O, Bellaiche N, Stamatakis H, Tsiklakis K, Walker A, et al. Variability of dental cone beam CT gray values for density estimations. Br J Radiol. 2013;86:20120135.

Mah P, Reeves TE, McDavid WD. Deriving Hounsfield units using gray levels in cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2010;39:323–35.

Magill D, Beckmann N, Felice MA, Yoo T, Luo M, Mupparapu M. Investigation of dental cone-beam CT pixel data and a modified method for conversion to Hounsfield unit (HU). Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2018;47:20170321.

González-García R, Monje F. The reliability of cone-beam computed tomography to assess bone density at dental implant recipient sites: a histomorphometric analysis by micro-CT. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24:871–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Helena de Oliveira and Dr. Geisa Medeiros for their early assistance with CT software.

Funding

The work was supported by a research grant from Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, Brazil; PNPD grant), the National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq, Brazil; Universal grant), and the International Team for Implantology (ITI, Switzerland; grant 688_2010).

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be deposited in a public repository because of the institutional requirements and policies of research data confidentiality. Selected anonymized data are available upon individual request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (1) made substantial contributions to the conception and/or design of the work or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; (2) drafted the paper or revised it critically; (3) approved the final version of this manuscript; and (4) agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Categories of authors’ contribution are as follows: concept/design (RSS, DFT, FRA, and LAM), data collection (DFT, FRA, LAM, MIR, and DRS), data analysis/interpretation (DFT, MIR, DRS, EAV, ERT, and RSS), drafting of the article (DFT, EAV, DRS, and RSS), critical revision of the article (DFT, FRA, LAM, MIR, DRS, EAV, ERT, and RSS), and approval of the article (DFT, FRA, LAM, MIR, DRS, EAV, ERT, and RSS). Funding was secured by RSS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the ethics committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul/UBEA (ethical approval letter OF.CEP-772/10; research protocol CEP 10/05074).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Competing interests

Diego Fernandes Triches, Fernando Rizzo Alonso, Luis André Mezzomo, Danilo Renato Schneider, Eduardo Aydos Villarinho, Maria Ivete Rockenbach, Eduardo Rolim Teixeira, and Rosemary Sadami Shinkai declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Triches, D.F., Alonso, F.R., Mezzomo, L.A. et al. Relation between insertion torque and tactile, visual, and rescaled gray value measures of bone quality: a cross-sectional clinical study with short implants. Int J Implant Dent 5, 9 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-019-0158-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-019-0158-6