Abstract

The backfilling of underground stopes in mines has become common practice in the mining industry as it increases the stability of mine excavations and reduces environmental problems. The backfilling process involves several technical aspects that must be assessed to ensure that the backfilling objectives are achieved. The horizontal stress exerted by backfill on excavation walls must be estimated accurately to avoid the failure of mine pillars. The analytical Marston method is often used for evaluating this stress as it takes into consideration an earth pressure coefficient (K) that is dependent on the geotechnical properties of the backfill. This paper demonstrates that the accuracy of the Marston method for predicting horizontal earth pressure would be improved by using K values that are determined as a function of backfill geotechnical parameters and also excavation geometry. Both components vary inevitably from one backfilled site to another. A methodology is developed to adjust the K value to be a function of these parameters for its application within the Marston analytical method thereby providing a more accurate prediction of earth pressure. Based on various geometric and geomechanical parameters, two graphs are developed to evaluate proper earth pressure values. These graphs can be used for estimating more accurate K values that are based on the characteristics of the stope and the backfill material.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mine backfilling is a technique that has been used for decades in Canada and across the globe [1, 2]. This method has several advantages such as stabilizing the drifts and stopes of a mine and increasing worker safety. Backfilling serves to fill excavations in a mine and allows ore to be extracted more completely because the underground excavations have better support. Environmental benefits result from the use of tailings as backfill material: problems related to the disposal of surface tailings can be reduced as substantial quantities of potentially polluting tailings can be returned underground. This backfill material generally consists of a mixture of tailings, water and cement.

The backfilling process has several technical aspects that interact with one another. This includes the hydrogeology, mineralogy and geochemistry of both the host rock and backfill material as well as the mechanical behavior of these two media. Mechanical interactions occur at the interface between the backfill and the host rock mass. The mechanical properties of these two media are very different from each other. For example, the backfill is of lower density and rigidity than the host rock. These contrasting properties must be accounted for in a thorough analysis of the mechanical interactions between the two media. The freshly placed backfill tends to compress under its own weight and generates shear stress at the backfill–rock interface due to friction. A certain amount of weight is transferred laterally from the backfill to the rock mass. This transfer is associated with arching, which occurs mostly in narrow stopes and where a lower density material is placed between denser materials [3, 4]. The stresses exerted on the mine pillars by the backfill must be determined to avoid failure of the pillars. This requires accurate estimates of the geomechanical parameters of both the backfill and the rock mass.

The arching effect has been demonstrated by several authors through field measurements or analytical and numerical models. Important studies on this topic include that of Li and Aubertin [3], which presents the results of large-scale numerical investigations focused on stope geometry and backfill properties. They conclude that the greatest effect on stress distribution within backfill results from the cohesion (c) and the friction angle (\( \upphi^{\prime } \)) of the backfill. However, the values of the earth pressure coefficient (K) used in these studies were obtained from the geotechnical engineering literature, particularly from analyses involving retaining walls, that applied values such as the Rankin, Coulomb and at-rest earth pressure coefficients [5]. These analytical methods were based on simplifying assumptions that excluded the possibly important variations in K resulting from changes in the geomechanical parameters (e.g., E and c) and excavation geometry, thereby affecting the accuracy of the stress distribution models.

Ting et al. [6] studied the stress distribution along an inclined stope focusing on several geomechanical and geometrical parameters. They demonstrated that the inclination of a stope is another critical factor for predicting stress distribution in backfill. However, they did not consider that K in backfill will vary inevitably with variations in stope geometry.

It is necessary to develop more accurate values of K that account for the variability of geometrical and geomechanical parameters. A method is proposed for modifying the value of K depending on the geometry of the excavation and the geomechanical parameters of the backfill. Graphs are developed to estimate K for different values of these parameters. This method is validated by comparing the resulting K values with values obtained using existing models and analytical approaches.

Analytical methods

Despite their limiting assumptions, analytical methods for estimating values of K, such as the method of Marston [7, 8] and overburden solutions [5], are useful to mining engineers as they can be used to obtain a preliminary K value. The Marston theory [7] is particularly suitable for sites where arching occurs. This theory accounts for both the weight of the fill and the shear forces between a vertical wall and the backfill at a given depth.

Figure 1 illustrates the parameters required for using the standard Marston and overburden methods to determine K for a backfilled stope having vertical walls. These methods require the following assumptions [9]:

-

The backfill is bounded by two parallel vertical walls;

-

A two-dimensional plain strain condition is present;

-

The vertical stress is uniformly distributed along a horizontal plane at all depths;

-

The adhesion between the rock face and the backfill is equal to the cohesion of the backfill.

In Fig. 1, H and B are, respectively, the height and width of the backfill. The backfill is subjected to a lateral compressive stress C, a shear force S and a vertical force V, all of which vary with depth Z. W represents the weight of the backfill per unit thickness. Thus,

where γ is the unit weight and dz is the thickness of the layer element in the backfill.

The equation for the balance of forces in the fill section th provides an estimate of the stresses acting throughout the backfill [3, 10]. From these deductions, the horizontal stress can be obtained from the equation:

where

The parameters σvz and σhz are, respectively, the vertical and horizontal stress at depth z, and δ is the interface friction angle, which is approximately 2/3 of \( \upphi^{\prime } \). Pirapakaran and Sivakugan [11] demonstrated that for a backfill cohesion of zero, t friction angle δ at the interface is approximately 2/3 of \( \upphi^{\prime } \) when K = K 0. However, depending on the blasting-related roughness and irregularities in the stope walls, this parameter could be considered as equivalent to the friction angle of backfill, i.e. \( \upphi^{\prime } \). Under these conditions, the estimated vertical stress obtained from the analytical model approximates the true value. The value of K depends on the material properties and the horizontal displacement of the wall.

Three cases were considered for estimating K in Marston theory [7]:

-

1.

When there is no relative displacement of the walls, the backfill isaid to be at rest (neutral), and K is equal to the at-rest earth pressure (K 0) given by Jaky [5]:

-

2.

When considering an active earth pressure coefficient (K a),

-

3.

When considering a passive earth pressure coefficient (K p),

Equation 2, developed by Marston [7], was used by Li et al. [10]. However, these two studies each proposed different definitions of the earth pressure coefficient (K): Marston [7] defined K as the active earth pressure developed by Rankine (K a = 0.33), whereas Li et al. [10] concluded that K 0 (approximately 0.5) was the most suitable value for vertical walls after they compared the at-rest (K 0), active (K a) and passive (K p) earth pressures.

Figure 2 presents a comparison between the overburden theory (σvz = γH and σhz = K σvz) and the Marston solution (Eq. 2) for horizontal and vertical stress when K is assigned a value of 0.5. The overburden theory does not account for any arching and σvz and σhz are linearly related. However, the Marston model [7] clearly indicates the presence of arching (Fig. 2) in that the curves of σhz and σvz gradually approach a stress limit. This arching occurs because the mass transfer to the stope walls is significant and tends to reduce the horizontal (σhz) and vertical (σvz) stresses on the walls [12]. Arching occurs only in narrow stopes, and the traditional overburden model can provide a meaningful estimate of the stresses in stope backfill near the top, where arching is insignificant, or when the width of the backfill is very large relative to the height.

Numerical modeling

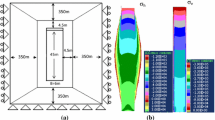

A series of numerical calculations were performed using the software Phase 2 [13] to check the validity of the analytical models. The model includes a narrow stope that is 45 m tall by 6 m wide, and has a base located at a depth of 250 m (Fig. 3a). The vertical stress σv at a given depth in the rock mass is obtained from the overburden weight at that depth. The horizontal stress (σH) in the rock mass is assumed to be twice that of the vertical stress (σV), typical for rock masses in the Canadian Shield [3]. This host rock is assumed to be isotropic, homogeneous, linear elastic that behaves in accordance with the failure criterion of Hoek and Brown [14]. The backfill is assumed to behave in accordance with the Mohr–Coulomb failure criterion. The interface between the backfill and the rock mass is represented by a joint in Phase 2. This joint is assigned a cohesion of 0 and an interface friction angle (δ) being 2/3 of the backfill friction angle (\( \upphi^{\prime } \) = 30°).

The results of the numerical modeling (Fig. 4) can be compared with estimates obtained from the analytical models. Figure 5 illustrates the arching in the backfill and the transfer of loads to the walls. Reductions in the vertical (σvz) and horizontal (σhz) stress, relative to the overburden weight, are indeed observed in the backfill from the top to the bottom of the stope. The stress distribution is nonuniform and, at any given elevation, the horizontal (sigma xx or σhz) and vertical (sigma yy or σvz) stresses are lower along the walls than in the center of the backfill.

Figure 5 shows the results of the analytical model for K values of 0.5 and 0.33, based on the findings of Marston [7] and Li and Aubertin [10]. for a narrow vertical stope having a backfill friction angle of 30°. The curve of the numerical model is below the curve of the analytical overburden model and nearly coincides with the curve of the Marston model that has a K value of 0.3. The question that arises is how to determine the value of K that is best suited for adjusting the analytical model to the numerical results for different values of the geomechanical and geometric parameters. The value of K is dependent on both the geomechanical parameters of the backfill and on the geometry of the stope. A suitable K value therefore varies with fluctuations in these parameters. An adjustment is necessary based on the geomechanical and geometric parameters of the backfill. Figure 5 shows that a K value of 0.33 yields a very good fit with the numerical model for a stope measuring 6 × 45 m.

Determination of the earth pressure coefficient based on geomechanical parameters

Several geomechanical parameters affect the distribution of vertical and horizontal stresses in the backfill, including friction angle (\( \upphi^{\prime } \)), cohesion (c), Young’s modulus (E), unit weight (γ) and Poisson’s ratio (ν). The relative importance of the effects of each parameter on K was determined from a sensitivity analysis in which several values were assigned to each of these parameters while keeping the other parameters constant.

Sensitivity analysis

The geomechanical parameters evaluated by the sensitivity analysis were the Young’s modulus E (Fig. 6), the cohesion (c) (Fig. 7) and the friction angle \( \upphi^{\prime } \) (Fig. 8) of the backfill.

The effect of Young’s modulus on horizontal stress in the backfill appears to be insignificant (Fig. 6). Variations in cohesion, however, produce a range of horizontal stress values of approximately 0.04 MPa. These values appear to be constant below a depth of 40 m (Fig. 7). When cohesion exceeds 0.1 MPa, the results remain similar and the curves are nearly superposed. The friction angle exerts by far the greatest effect on horizontal stress (Fig. 8), as it produces horizontal stress values having a range of 0.15 MPa. The estimated horizontal stress increases gradually with decreasing friction angles (\( \upphi^{\prime } \)), and arching occurs for every value of \( \upphi^{\prime } \). This arching is evident in the stabilization of the curves at the bottom of the stope. Figure 6 indicates that the variation of Young’s modulus in the backfill has negligible effects on the distribution of horizontal stress when compared with the variations in the friction angle. Furthermore, as shown in Fig. 7, a backfill cohesion value of more than 50 kPa above the variation of vertical stress does not have a substantial effect on vertical stress. Friction angle has a much greater effect on the estimated horizontal stress than does the Young’s modulus and cohesion. Therefore, only the friction angle was subsequently used to obtain a corrected value for the earth pressure coefficient.

Analytical and numerical adjustment

The analytical model of Marston [7] can be adjusted based on the results of numerical modeling by varying the value of K in the Marston equation (Eq. 2) so that the analytical and the numerical curves overlap. By gradually changing the value of K, it is possible to obtain nearly perfectly matching curves. This yields the appropriate K value for use with the corresponding values of these geomechanical parameters.

Figures 9 and 10 show the curve fitting process for determining the appropriate value of K for various values of \( \upphi^{\prime } \) in two similar models having a height/width (H/B) ratio of 7.5, specifically models measuring 6 × 45 m and 12 × 90 m. The curve fitting has been determined by trial and error. These two figures indicate that the best-fit values of K decrease with increasing \( \upphi^{\prime } \). Moreover, the best-fit K values are the same in these two systems having the same H/B ratio. Stopes of similar geometry (with similar arching), for example with a backfill having \( \upphi^{\prime } \) = 15°, will have a K value of approximately 0.55. Backfill having \( \upphi^{\prime } \) = 20° will have a K value of 0.45, and so forth. Appropriate K values can be determined for stopes of any size having a similar H/B ratio. The Rankin active K value used in Eq. 5 is presented in Figs. 9 and 10. From this, we see that there is a greater difference between the two curves. Thus, only using the active Rankin equation can lead to greater error in estimating backfill pressure.

Figure 11 shows that the best-fit value of K decreases considerably (from 0.6 to 0.15) as the friction angle (\( \upphi^{\prime } \)) increases from 10° to 50°.

Determination of the earth pressure coefficient based on stope geometry

As discussed above, mass transfer due to shearing and arching is possible only in narrow stopes. It is therefore important to determine the variation of K associated with different stope geometries, including the geometric threshold at which arching—strong or weak—occurs gradually in the backfill. A low H/B ratio likely produces very little arching because very little friction is generated at the backfill–rock interface. In addition, a value of K can be estimated for each H/B value. This permits the determination of several best-fit K values and thus yields more accurate results for determining horizontal stress (σhz).

Figure 12 illustrates the estimates of horizontal stress based on numerical models of several backfilled stopes of the same height (H = 45 m) but having various widths (B) ranging from 4.5 to 22.5 m. The geomechanical parameters, such as cohesion, friction angle and Young’s modulus, are held constant in all models at the values shown in Fig. 3. Figure 12 clearly shows that arching is greater at higher H/B ratios, resulting in a slower increase in horizontal stress with depth. The arching effect is visible in the stabilization of the curve, i.e. the decreasing slope. At the other extreme, the curve for an H/B of 2 shows very little arching, approaching that of the overburden model. In this case, the horizontal stress continues to increase. The curve for an H/B of 10 shows substantial arching, and the increasing rate of σhz and σvz decrease toward the footwall. In summary, the arching effect appears to be negligible at an H/B of 2 and gradually increases with higher H/B ratios.

It is clear from Fig. 12 that altering the geometry changes sigma xx substantially. Therefore, a single K value cannot be applied. An appropriate K value must be obtained for a given H/B ratio and for given values of geomechanical parameters, such as the friction angle (\( \upphi^{\prime } \)).

To validate the representativeness of the H/B ratio as a standard geometric parameter, Fig. 13 presents the numerical results corresponding to different stopes having the same H/B value of 7.5. Depth (Z) is normalized to total height (H). As such, the normalization is applied to the stress values by dividing the actual horizontal stress estimates by the maximum value, which is present at the bottom of the stope (Fig. 13). In this case, the curves overlap almost perfectly, producing a curve that represents all model configurations having an H/B ratio of 7.5. This superposition confirms the validity of the H/B ratio as a reference parameter for determining the value of K in stope backfill.

Similar to the analysis of the friction angle presented in Figs. 9, 10 and 11, a best-fit value for K can be determined as a function of the geometry represented by the H/B ratio. This step was performed by adjusting the analytical model of Marston based on the results of the numerical models. It is assumed that with a given set of geomechanical parameters, the appropriate K value obtained from this adjustment is the same for all stopes having an identical H/B ratio. Figure 14 illustrates the case where H/B = 7.5 and the appropriate K value for backfilled stopes of three different sizes is 0.33. The results are consistent with Marston theory for this set of geometric and geomechanical parameters.

The K value can be determined for different values of the H/B ratio. For a given set values of geomechanical parameters, the value of K gradually decreases with increasing H/B ratios (Figs. 15, 16 and 17). An appropriate value of K can therefore be determined for each value of this ratio.

A graphic method for application to the Marston solution

Figures 18 and 19 allow for determining an appropriate K value by adjusting the analytical method of Marston for stopes of various geometries and backfills having various geomechanical parameter values. These graphs were developed from the numerical modeling results in comparison with estimates obtained via the Marston method [7]. These graphs serve as charts for determining the earth pressure coefficient based on the friction angle and various H/B ratios. Figure 18 (in which δ = \( \upphi^{\prime } \)) is complementary to Fig. 19, the latter able to be applied to stopes having a minimal wall roughness (δ = 2/3\( \upphi^{\prime } \)).

Conclusions

This study suggests that the determination of the earth pressure coefficient (K) must account for the stope geometry and geomechanical parameters of the backfill as these parameters can vary markedly even within a given mine. In general, most authors do not adjust the value of K based on their model parameters and instead apply a constant K value.

A sensitivity analysis of the geomechanical parameters demonstrated the relative effects of cohesion, Young’s modulus and friction angle of the backfill on the estimates of horizontal stress; the friction angle (\( \upphi^{\prime } \)) exerts the greatest effect.

Two charts were developed and provide improved estimates of the earth pressure coefficient (K). They are based on the Marston solution and account for both the stope geometry (the H/B ratio) and the geomechanical parameters (the friction angle \( \upphi^{\prime } \)) of the backfill. This method provides more accurate estimates of the earth pressure coefficient and reflects the often heterogeneous characteristics of backfilled stopes.

Abbreviations

- \( \upphi^{\prime } \) :

-

friction angle of the backfill (degrees)

- \( \upphi^{\prime } \) res :

-

residual friction angle of the backfill (degrees)

- B:

-

stope width (m)

- H:

-

height of the backfill (m)

- H/B:

-

height/width ratio of the backfill

- c:

-

cohesion of the backfill (N/m2)

- cres :

-

residual cohesion of the backfill (N/m2)

- K :

-

earth pressure coefficient

- K a :

-

active earth pressure coefficient (thrust)

- K p :

-

passive earth pressure coefficient

- K 0 :

-

at-rest earth pressure coefficient

- V:

-

vertical force at depth Z (N)

- W:

-

backfill weight (N)

- m, s:

-

constants in the Hoek and Brown failure criterion for the rock mass

- C0 :

-

uniaxial compressive strength in the intact rock

- Z:

-

depth below the top of the backfill (m)

- Z/H:

-

normalized height at depth Z

- γ:

-

unit weight of the backfill (MN/m3)

- δ:

-

friction angle along the interface between the backfill and stope wall

- E:

-

Young’s modulus of the rock or backfill (MPa)

- ν:

-

Poisson’s ratio of the rock mass or backfill

- σhz = sigma xx :

-

Horizontal stress exerted by the backfill on the wall at depth Z (Pa)

- σvz = sigma yy :

-

Vertical stress at depth Z (Pa)

- τ:

-

shear stress along the stope wall at depth Z (Pa)

- σH :

-

in situ horizontal stress in the rock mass

- σV :

-

in situ vertical stress in the rock mass

References

Hassani FP, Scoble MJ, Yu T (1989) Innovation in mining backfill technology. In: Proceedings of 4th international symposium mining with backfill

Thomas EG (1979) Fill technology in underground metalliferous mines. University of British Columbia, Department of Mineral Engineering

Li L, Aubertin M (2008) An improved analytical solution to estimate the stress state in subvertical backfilled stopes. Can Geotech J 45:1487–1496

Handy RL (1985) The arch in soil arching. J Geotech Eng 111(3):302–318. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1985)111:3(302)

Bowles JE (1996) Foundation analysis and design, 5th edn. Mcgraw-Hill, New York

Ting CH, Shukla SK, Sivakugan N (2011) Arching in soils applied to inclined mine stopes. Int J Geomech 11:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0000067

Marston A (1930) The theory of external loads on closed conduits in the light of the latest experiments. In: Highway research board proceedings. Bulletin no. 96, Iowa, Engineering Experiment Station, Ames

McCarthy DF (2006) Essentials of soil mechanics and foundations: basic geotechnics, 7th edn. Prentice Hall. ISBN-10: 0131145606

Ting C, Shukla S, Sivakugan N (2010) Arching in soils applied to inclined mine stopes. Int J Geomech 11:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GM.1943-5622.0000067

Li L, Aubertin M (2009) Numerical investigation of the stress state in inclined backfilled stopes. Int J Geomech 9:52–62

Pirapakaran K, Sivakugan N (2007) A laboratory model to study arching within a hydraulic fill stope. Geotech Test J 30:496

Knutson S (1981) Stresses in the hydraulic backfill from analytical calculation and in-situ measurements. In: Proceeding conference on the application of rock mechanics to cut and fill mining. pp 261–268

Rocscience A (2015) 2D finite element program for calculating stresses and estimating support around the underground excavations. In: Geomechanics Software and Research Inc., Toronto

Hoek E, Kaiser PK, Bawden WF (2000) Support of underground excavations in hard rock. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Authors’ contributions

AS determined the idea of the paper determined by. YL and AS carried out the numerical modelling. YL, AS and AR wrote the paper. All work supervised by AS and AR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Levesque, Y., Saeidi, A. & Rouleau, A. An earth pressure coefficient based on the geomechanical and geometric parameters of backfill in a mine stope. Geo-Engineering 8, 27 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40703-017-0065-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40703-017-0065-8