Abstract

Background

Parrots (Psittacidae Family) are one of the most colorful groups of birds in the world, their colors produced both structurally and via unusual pigments (psittacofulvins). Most species are considered to be monogamous, and many have been viewed historically as sexually monomorphic and monochromatic. However, studies using morphometric analysis and spectrophotometric techniques have revealed sexual size dimorphism and also sexual plumage color dimorphism among some species. The Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus), a native parrot of South America, is an interesting species for the study of plumage coloration and size since it is considered sexually monochromatic and monomorphic. Furthermore, recent studies show that the Monk Parakeet has extra-bond paternity behavior and even breeding trios, which suggests that sexual selection may play an important role in this species, and that it might have sexually dimorphic plumage (albeit imperceptible by humans) and be dimorphic in size.

Methods

For the determination of plumage color we used spectrophotometry in the range of avian vision (300‒700 nm) and performed a morphological analysis.

Results

Our spectrophotometric results indicate that the Monk Parakeet shows subtle sexual plumage color dimorphism in three (crown, nape and wing) out of twelve body regions. Similarly, our morphometric analysis showed that there are subtle sex differences in body size (bill and weight).

Conclusions

Although the Monk Parakeet shows extra-bond paternity and breeding trio behaviors which could increase sexual dimorphism, these behaviors occur among highly related individuals; perhaps the high rate of inbreeding is responsible for the attenuation of sexual plumage color dimorphism and sex differences in body size observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In birds, coloration is one of the most important traits linked to social status, physiological state and sexual behavior (Hill and McGraw 2006). Parrots inhabiting different regions of the world constitute a group that has received special attention largely because of their colorful displays (del Hoyo et al. 1992). The wide variation in coloration observed in parrots is mainly the product of the nano-structure of their feathers (structural coloration) plus the presence of different kinds of pigments (melanins and a unique kind of pigment called psittacofulvins) (Stradi et al. 2001; McGraw and Nogare 2004; Berg and Bennett 2010). Furthermore, like all diurnal avian species, parrots perceive plumage coloration differently from mammals thanks to their tetrachromatic visual system, which includes a UV photoreceptor (Vorobyev et al. 1998). Because of this difference in the avian visual system, studies of plumage coloration relating to intra-specific signaling should assess coloration in a way that takes into account how color is perceived by other birds, especially in those species classified as sexually monochromatic according to the human visual system (del Hoyo et al. 1992). This is important since for a long time it was thought that sexual differences in plumage coloration and size tended to be weaker in monogamous than in polygamous species (Andersson 1994). Owens and Hartley (1998) demonstrated for the first time that size dimorphism and plumage color dimorphism in birds do not vary in the same way. They concluded that sexual differences in size are associated with the kind of mating system characteristic of the species and with sexual differences in parental care, that is, greater sexual differences in size at higher levels of polygamy and less parental care of the male. In terms of sexual differences in plumage coloration, they determined these to be associated with high levels of frequency of extra bond paternity exhibited by the bird species (Owens and Hartley 1998). Added to this, it has been reported that in the Psittacidae family, two South American species (Blue-fronted Amazon Amazona aestiva and the Burrowing Parrot Cyanoliseus patagonus) which are considered monogamous and without sexual size dimorphism, exhibit differences between sexes that are visually indistinguishable by humans (Santos et al. 2006; Masello et al. 2009). Although providing information on only two South American species, these studies suggest that incorporating the UV region into the discrimination analysis may reveal that sexual plumage color dimorphism could be more frequent than previously thought (Hausmann et al. 2003; Santos et al. 2006; Masello et al. 2009).

In this context, the Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus), another Psittacidae family member native to South America, which has hitherto been considered to be sexually monomorphic, presents an interesting case for study of plumage color and size dimorphism (del Hoyo et al. 1992). The Monk Parakeet is a colonial parrot considered to be socially monogamous; however, recent genetic studies provide evidence of extra-pair paternity, breeding trios and cases of intra-brood parasitism (Martínez et al. 2013; Bucher et al. 2016). During summer, the Monk Parakeet uses sticks to build nests with multiple individual chambers occupied by different pairs and to a lesser extent by trios (del Hoyo et al. 1992; Spreyer et al. 1998; Forshaw 2010; Hobson et al. 2014, 2015).

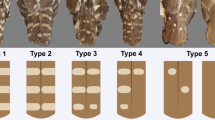

Like other parrots, the Monk Parakeet has a combination of structural and pigmentary coloration: to the human eye it looks green over most of its body, gray on its head and belly, and blue on the flight feathers. No studies have quantified plumage color dimorphism and little regarding to size dimorphism (Martinez et al. 2018) in this parrot. Based on the background data above, we aimed to determine whether adult Monk Parakeet males and females exhibit sexual plumage color dimorphism and size dimorphism in any of their body regions. To this end, we used spectrophotometry to objectively measure plumage reflectance across the visible spectrum of birds (300–700 nm) and performed morphometric analysis.

Methods

Thirty-two adult wild male and thirty-six adult wild female Monk parakeets (Psittacidae family, Psittacinae subfamily, tribe Arini) were captured inside Córdoba Zoo, Argentina (31° 25′ 31.79″ S, 64° 10′ 29.92″ W) with passive traps, following the procedure described in Valdez and Benitez-Vieyra (2016) to trap doves. Captures were made during May and June 2017, thus avoiding the molting period in the Southern hemisphere (December to April) (Navarro et al. 1992). All animals were sacrificed using sodium pentobarbital and sexed by examination of the reproductive organs; the skins were then used in the spectrophotometry measurements. We determined and compared the reflectance spectrum of twelve different body regions: forehead, crown, cheeks, nape, back, chest, belly, blue wing coverts, green wing coverts, primary and secondary remiges, and tail (on all upper surfaces). The animals were sacrificed as part of a neuroendocrine study.

Color measurements and analysis

Bird coloration cannot be accurately analyzed with tools designed for human vision, as birds perceive colors in a radically different way. Thus, we carried out all reflectance measurements within the avian spectral sensitivity range (300–700 nm, Bowmaker et al. 1997) using an Ocean Optics USB4000 spectrophotometer equipped with a halogen and a deuterium light source (830 Douglas Ave., Dunedin, FL, USA 34698), both connected to the sensor by a bifurcated fiber optic cable. Each plumage region was illuminated, and the light reflected at 45° was collected. The distance between the probe and the plumage was 4 mm, the spectrophotometer resolution 0.19 nm, the integration time 300 ms and each spectrum was the average of three readings. A white standard (Ocean Optics, WS-1-SS White Standard) was used to re-calibrate the equipment between measurements in order to correct for possible shifts in performance. Reflectance was measured using SpectraSuite software (Ocean Optics, Inc.).

After obtaining reflectance spectra, we applied a receptor-noise limited model of avian vision (Vorobyev et al. 1998) to estimate how avian receivers of chromatic signals would perceive the parakeets’ plumage colorations. This model takes into account the number and sensitivity of color receptors in the avian eye (cones) and how color information is processed in terms of signal-to-noise ratio, assuming that color discrimination is limited by photoreceptor noise. To apply an avian visual model to reflectance data, we used the pavo 2.4.0 package (Maia et al. 2013) for R (Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing 2013). Cone quantum catch (Q) for each of the four avian cones was calculated under standardized daylight illumination (D65) as a representative spectrum for open habitat ambient light at midday, similar to the type of habitat that this species frequents. We used UV-type avian eyes for spectral cone sensitivities as a general representative of the parrot visual system (Bowmaker et al. 1997). Although cone parameters have not been measured in M. monachus, we used the generalized spectral cone sensitivities of the UV-type of Melopsittacus undulatus eyes since this is the only member of the Psittaciformes that has been characterized to date (Bowmaker et al. 1997; Goldsmith and Butler 2005; Lind et al. 2014). Contrasts between males–males, males‒females and females–females were characterized in units of “just noticeable differences” (JND), such that one JND represents the threshold of possible discrimination. Chromatic (dS) and achromatic (dL) distances were calculated in JNDs following the vision model using cues. Visual stimuli separated by one JND are discernible by birds, although only under ideal illumination (Olsson et al. 2015).

Morphometric measurements

For each Monk Parakeet we measured the height, width and length of the bill (from the tip to the base of the skull), length of the tarsus, total length and wing length. For this we used a digital caliper (range 0‒150 mm; resolution 0.01 mm; accuracy ± 0.02 mm) and a millimeter metal ruler (50 cm). The animals were also weighed with a PESOLA® brand spring scale (accuracy ± 2 g).

Statistical analyses

First, we examined the mean ± 2SE reflectance spectra of males and females to determine the presence of overlapping regions. Then, we calculated all pairwise chromatic and achromatic distances (measured in JNDs) among males, among females, and between males and females, for each body region. We tested whether between-sex differences were greater than within-sex differences using a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA, Anderson 2001), as implemented in the adonis function of the vegan R package (Oksanen 2017). PERMANOVA is a multivariate analogue of the univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) where multivariate variance is partitioned in the space of any arbitrary dissimilarity measure, JNDs in our case. In this test, significance is obtained by comparing the multivariate version of the F-statistic with the results obtained under a large number of permutations. We performed 24 PERMANOVAs (12 for achromatic distances and 12 for chromatic distances) to test for differences between sexes in each body part. Each test involved 999 permutations. We considered the observed distance between sexes to be significantly different from that expected by random chance if it was greater than 95% of the randomized values.

Finally, we examined the multivariate morphological variation between sexes in the six traits detailed above by principal component analysis (PCA). In addition, we applied a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to test for multivariate differences between sexes. In contrast with color cues, differences in morphology can be expressed in terms of euclidean distances among individuals, fulfilling the assumptions of common (parametric) MANOVA. When a significant effect was detected, we performed additional univariate nested ANOVAs to determine which traits accounted for the significant effect in the MANOVA.

Results

Reflectance spectra

No noticeable differences between sexes were observed in spectral shape for any of the studied body regions. There was considerable overlapping of mean reflectance values in some regions. The comparison between the mean ± 2SE reflectance spectra of males and females for the twelve different body regions examined throughout the avian visual range (300‒700 nm) is shown in Fig. 1b.

Achromatic and chromatic distances (JNDs)

The achromatic and chromatic distances in JNDs among males, among females and between males and females are shown in Fig. 2. In all body regions examined, mean achromatic distances were higher than 1 JND (discrimination limit under ideal illumination). These indicate that on average, individuals could be distinguished based on achromatic cues, even when they are of the same sex (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, mean achromatic distances were not significantly different between sexes (PERMANOVA, in all cases F1,67 < 4.117 and p > 0.06), with the exception of the blue wing coverts (F1,67 = 5.512, p = 0.021) and nape (F1,67 = 4.524, p = 0.042).

Achromatic and chromatic distances after applying an avian visual model. Mean values ± standard deviations of achromatic and chromatic distances measured as just noticeable differences (JNDs) following a receptor-noise limited model of avian color vision. Vertical dotted lines indicate the discrimination threshold of one JND. At values below 1, individual chromatic and achromatic cues cannot be distinguished. Permutational multivariate analyses of variance (PERMANOVAs) were used to test whether or not differences between sexes were greater than within sexes. Significant differences (p < 0.05) are indicated with an asterisk (*)

In the mean chromatic distances, we found that three (forehead, cheeks and belly) of the twelve body regions studied were below the discrimination limit 1, indicating that individuals cannot be distinguished based on these cues. In the other nine corporal regions (crown, nape, back, chest, blue wing coverts, green wing coverts, primary remiges, secondary remiges and tail) mean chromatic distances were equal or higher than the discrimination limit. In seven corporal regions (nape, back, chest, green wing coverts, primary remiges, secondary remiges and tail) no significant differences between males and females were observed (PERMANOVA, in all cases F1,67 < 3.076, p > 0.090) (Fig. 2). The only two exceptions were the blue wing coverts (PERMANOVA, F1,67 = 4.28, p = 0.025) and the crown (F1,67 = 5.659, p = 0.013). However, notice that the average color distance between sexes for the crown was only 1.109 JNDs (Fig. 2), suggesting that this difference between sexes is hardly noticeable for birds.

Morphometric measurements

The first three principal components of the PCA explained 72.31% of the total variation recorded among individuals (Fig. 3). All traits had positive, similar loadings on PC1, suggesting that this component is associated with general differences in size among individuals (Table 1). Bill traits and total weight attained positive loadings on PC2, while wing length, tarsus length and total length attained negative loadings (Table 1). Thus, positive PC2 scores correspond to heavier birds with more prominent bills, but with shorter wings, tarsus and total length. The opposite is true for individuals with negative PC2 scores. Finally, total length had a strong positive loading on PC3, while bill width attained a strong and negative score (Table 1), indicating that this PC expresses differences among individuals in these traits. MANOVA indicated that there were significant differences between sexes (Wilks’ λ = 0.554, p < 0.0001) and univariate ANOVAs showed these differences to be accounted for by body weight (F1,66 = 18.524, p = 0.0001), bill height (F1,66 = 27.118, p < 0.0001), bill length (F1,66 = 13.471, p = 0.0005) and bill width (F1,66 = 25.183, p < 0.0001), but not by tarsus, wing and total length (in all cases F1,66 < 2.038, p > 0.158; Fig. 3).

Morphometric analysis of the Monk Parakeet. Morphological differences between sexes in Monk Parakeet. a PCA for the five variables analyzed (height, width and length of the bill; length of the tarsus; total length, total weight and wing length). Polygons indicate convex hulls, and females are in orange and males in blue. b Box and whisker plots of those morphometric variables for which significant differences were detected using one-way ANOVAs. Boxes indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles (lower and upper quartiles, respectively) of the distribution, while the central band indicates the median. “Whiskers” indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range. Points indicate outliers

Discussion

In this work we examined the sexual plumage color dimorphism and size dimorphism in the colonial breeder Monk Parakeet (M. monachus) using an objective methodology (spectrophotometry) and morphometric analysis. The superposition of the reflectance spectra shows that overall, mean reflectance values are the same for both sexes in all body regions studied (see Fig. 1b). On the other hand, the achromatic and chromatic distances obtained with the avian visual model indicate a subtle sexual plumage color dimorphism in this parrot. Analysis of the mean pairwise achromatic distances showed all body regions to be above the discrimination limit for both sexes, with only slight differences between males and females for only blue wing coverts and nape. These findings may indicate that males and females are able to differentiate among individuals but not discern their sex based on plumage brightness. An interesting result regarding the parakeets’ blue wing coverts is that they have mean achromatic distances above the discrimination level along with significant differences between the sexes. These feathers are only visible when the birds are flying, and are hidden when they are resting. This leads us to the question of the role these feathers play in sex differentiation: could they be involved in sex recognition during flight? Are they involved in mate choice? More detailed studies are necessary to answer these questions. Furthermore, the differences between male and female Monk Parakeets’ nape achromatic distances are subtle (see Fig. 2), with values close to the discrimination limit, making it difficult to gauge the biological significance of the findings. Regarding the chromatic distances, three body regions showed chromatic distance values below the discrimination threshold, indicating that it is unlikely that individuals could be distinguished based on the coloration of these regions. The nine remaining body regions had distance values equal to or higher than the discrimination limit and seven of them did not show significant differences between males and females. The blue wing coverts and the crown were the only body regions observed to differ between males and females. The blue wing coverts were the only body region showing significant differences in both distances, but again, these feathers are hidden at rest and are only visible during flight.

The crown on the other hand is of particular interest since it is involved in both social behavior and mate choice in different bird species (Bennett et al. 1997; Andersson and Andersson 1998; Siitari et al. 2002; Delhey et al. 2003). The differences between the male and female Monk Parakeet’s crown are subtle (see Fig. 2), with values close to the discrimination limit (as in the case of the chest), again making it difficult to gauge the biological significance of the findings. Further experiments under controlled conditions should be carried out in order to evaluate whether the crown is linked to mate choice or other social behavior. Similar results were obtained with the morphometric analysis, where statistically significant differences between the sexes were only observed in terms of bill size and body weight. Again, the differences in bill size and body weight were subtle (just 1 mm in bill size and 5 g between sexes), so it is open to question whether parrots are able to discriminate these differences. Martínez and coworkers (Martinez et al. 2018) found that heavier Monk Parakeet males with larger beaks are paired with heavier females and with larger beaks, but this may be because (similarly to Burrowing Parrot C. patagonus) the Monk Parakeets could form longlasting pair-bonds from an early age and no for assortative mating (Martín and Bucher 1993). The only way to corroborate this idea is by performing experiments under controlled conditions.

Within the context of the sexual plumage color dimorphism and size dimorphism in birds raised by Owens and Hartley (1998), our results are relevant since they are the first to describe these albeit subtle traits in the Monk Parakeet. In their work, Owens and Hartley studied the relationship between the degree of sexual differences in size, plumage color dimorphism, the kind of mating system, degree of parental care (greater sexual differences in size at higher levels of polygamy and less parental care of the male) and degree of extra-bond paternity displayed by birds (greater sexual differences in plumage coloration at high levels of frequency of extra bond paternity). As already mentioned, Owens and Hartley observed a relation between the sexual plumage color dimorphism for structural coloration (as observed in parrots) and the level of a species’ extra-bond paternity. An example of the pattern described by Owens and Hartley is observed in another South American parrot, the Burrowing Parrot (C. patagonus), which is genetically monogamous and practices biparental care (Masello et al. 2002). Only with the use of spectrophotometry could a slight sexual plumage color dimorphism in the green and blue regions (differed in brightness) while the red region differed in spectral shape (reddish ventral patch) and a slight size dimorphism be observed in these birds, males being around 5% larger than females (Masello and Quillfeldt 2003, 2009). This finding corroborates the idea raised by Owens and Hartley (smaller differences in size and more parental care in monogamous species and subtle differences in coloration in species with low frequency of extra-bond paternity). In addition, despite the fact that the fundamental unit of social structure in Monk Parakeet populations is the pair (Hobson et al. 2014, 2015), which would indicate them to be monogamous, the populations studied by Martinez et al. and Bucher et al. show extra-bond paternity (EBP) behaviors, intra-specific parasitism (ISP) and reproductive trios (RT) (Martínez et al. 2013; Bucher et al. 2016). But the fact is that these behaviors in Monk Parakeets occur in a context of high inbreeding (Bucher et al. 2016); that is, the exhibited EBP, ISP and RT behaviors always occur between highly related individuals, resulting in high levels of inbreeding. This inbreeding phenomenon could be partly explained by the low dispersal distance (~ 2 km) of this species in its native South American distribution (Martín and Bucher 1993). The opposite phenomenon is observed when the Monk Parakeet behaves as an invasive exotic species in other regions of the world, where its dispersion distance can reach up to 100 km, favoring a reduction in inbreeding parameters (Da Silva et al. 2010). The high inbreeding values found by Bucher and coworkers could act as an attenuating factor of the sexual dimorphism observed in the Monk Parakeet and could explain the subtle sexual plumage color dimorphism and size dimorphism findings in our work. More detailed studies at the level of coloration and size are required to shed more light on this issue.

Since the Monk Parakeet appears to exhibit subtle sexual plumage color dimorphism and size dimorphism, the question then arises as to how males and females are able to tell themselves apart in order to form couples. Unlike in the case of the Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus), where sex differences in cere color and vocalization have been documented (Baltz and Clark 1996; Nespor et al. 1996; Hile et al. 2000), it is not possible to study cere color in the Monk Parakeet because the cere is covered by feathers of the same color as the forehead; and only group vocalizations have been studied within Monk Parakeet colonies during social interactions (threat call, alarm call, flight call, contact call, etc.) (Martella and Bucher 1990). Whether or not there are sex differences in this species’ vocalization therefore remains undetermined. Behavioral sex differences have been reported in different species of parrots (repetitive strutting, raised crests, strutting back and forth along a perch, head bowing, flaring the wings, etc.) (del Hoyo et al. 1992), but only repetitive strutting behaviors have been observed in the Monk Parakeet (Eberhard 1998), indicating that it is perhaps a combination of calls and behaviors that make the sexes distinguishable from one another.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reports a subtle sex plumage color dimorphism and size dimorphism in a species of a colonially breeding parrot native to South America, the Monk Parakeet. Comprehensive studies aimed at discriminating sex differences in calls and behaviors should be carried out in order to arrive at a better understanding of sexual recognition in this species.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets (data tables and scripts) supporting the conclusions of this article are available upon request.

References

Andersson MB. Sexual selection. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1994.

Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26:32–46.

Andersson S, Andersson M. Ultraviolet sexual dimorphism and assortative mating in blue tits. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 1998;265:445–50.

Baltz AP, Clark AB. Cere colour as a basis for extra-pair preferences of paired male budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus: Psittacidae: Aves). Ethology. 1996;102:109–16.

Bennett AT, Cuthill IC, Partridge JC, Lunau K. Ultraviolet plumage colors predict mate preferences in starlings. P Natl Acad Sci. 1997;94:8618–21.

Berg ML, Bennett AT. The evolution of plumage colouration in parrots: a review. Emu. 2010;110:10–20.

Bowmaker J, Heath L, Wilkie S, Hunt D. Visual pigments and oil droplets from six classes of photoreceptor in the retinas of birds. Vision Res. 1997;37:2183–94.

Bucher EH, Martínez JJ, de Aranzamendi M. Genetic relatedness in Monk Parakeet breeding trios. J Ornithol. 2016;157:1119–22.

Da Silva AG, Eberhard JR, Wright TF, Avery ML, Russello MA. Genetic evidence for high propagule pressure and long-distance dispersal in monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) invasive populations. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:3336–50.

del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Christie D. Handbook of the birds of the world, vol. 4. Barcelona: Lynx edicions; 1992.

Delhey K, Johnsen A, Peters A, Andersson S, Kempenaers B. Paternity analysis reveals opposing selection pressures on crown coloration in the blue tit (Parus caeruleus). P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2003;270:2057–63.

Eberhard JR. Breeding biology of the Monk Parakeet. Wilson Bull. 1998;110:463–73.

Forshaw JM. Parrots of the world. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2010.

Goldsmith TH, Butler BK. Color vision of the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus): hue matches, tetrachromacy, and intensity discrimination. J Comp Physiol A. 2005;191:933–51.

Hausmann F, Arnold KE, Marshall NJ, Owens IP. Ultraviolet signals in birds are special. P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 2003;270:61–7.

Hile AG, Plummer TK, Striedter GF. Male vocal imitation produces call convergence during pair bonding in budgerigars, Melopsittacus undulatus. Anim Behav. 2000;59:1209–18.

Hill GE, McGraw KJ. Bird coloration: function and evolution. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2006.

Hobson EA, Avery ML, Wright TF. The socioecology of Monk Parakeets: insights into parrot social complexity. Auk. 2014;131:756–75.

Hobson EA, John DJ, Mcintosh TL, Avery ML, Wright TF. The effect of social context and social scale on the perception of relationships in monk parakeets. Curr Zool. 2015;61:55–69.

Lind O, Chavez J, Kelber A. The contribution of single and double cones to spectral sensitivity in budgerigars during changing light conditions. J Comp Physiol A. 2014;200:197–207.

Maia R, Eliason CM, Bitton PP, Doucet SM, Shawkey MD. pavo: an R package for the analysis, visualization and organization of spectral data. Methods Ecol Evol. 2013;4:906–13.

Martella MB, Bucher EH. Vocalizations of the monk parakeet. Bird Behav. 1990;8:101–10.

Martín LF, Bucher EH. Natal dispersal and first breeding age in monk parakeets. Auk. 1993;110:930–3.

Martínez JJ, de Aranzamendi MC, Masello JF, Bucher EH. Genetic evidence of extra-pair paternity and intraspecific brood parasitism in the monk parakeet. Front zool. 2013;10:68.

Martinez JJ, de Aranzamendi MC, Bucher EH. Quantitative genetics in the monk parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus) from central Argentina: Estimation of heritability and maternal effects on external morphological traits. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0201823.

Masello JF, Lubjuhn T, Quillfeldt P. Hidden dichromatism in Burrowing Parrots Cyanoliseus patagonus as revealed by spectrometric colour analysis. Hornero. 2009;24:47–55.

Masello JF, Quillfeldt P. Body size, body condition and ornamental feathers of Burrowing Parrots: variation between years and sexes, assortative mating and influences on breeding success. Emu. 2003;103:149–61.

Masello JF, Sramkova A, Quillfeldt P, Epplen JT, Lubjuhn T. Genetic monogamy in burrowing parrots Cyanoliseus patagonus? J Avian Biol. 2002;33:99–103.

McGraw K, Nogare M. Carotenoid pigments and the selectivity of psittacofulvin-based coloration systems in parrots. Comp Biochem Phys B: Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;138:229–33.

Navarro J, Martín L, Bucher E. El uso de la muda de remiges para determinar clases de edad en la cotorra (Myiopsitta monachus). El Hornero. 1992;13:261–2.

Nespor AA, Lukazewicz MJ, Dooling RJ, Ball GF. Testosterone induction of male-like vocalizations in female budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Horm Behav. 1996;30:162–9.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O’hara RB, et al. vegan: community ecology package. R package. 2017.

Olsson P, Lind O, Kelber A. Bird colour vision: behavioural thresholds reveal receptor noise. J Exp Biol. 2015;218:184–93.

Owens IP, Hartley IR. Sexual dimorphism in birds: why are there so many different forms of dimorphism? P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci. 1998;265:397–407.

Santos SICO, Elward B, Lumeij JT. Sexual dichromatism in the Blue-fronted Amazon Parrot (Amazona aestiva) revealed by multiple-angle spectrometry. J Avian Med Surg. 2006;20:8–14.

Siitari H, Honkavaara J, Huhta E, Viitala J. Ultraviolet reflection and female mate choice in the pied flycatcher. Ficedula hypoleuca. Anim Behav. 2002;63:97–102.

Spreyer MF, Bucher EH, Poole A, Gill F. Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus). Birds N Am. 1998;322:322.

Stradi R, Pini E, Celentano G. The chemical structure of the pigments in Ara macao plumage. Comp Biochem Phys B: Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;130:57–63.

Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013.

Valdez DJ, Benitez-Vieyra SM. A spectrophotometric study of plumage color in the Eared Dove (Zenaida auriculata), the most abundant South American Columbiforme. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0155501.

Vorobyev M, Osorio D, Bennett A, Marshall N, Cuthill I. Tetrachromacy, oil droplets and bird plumage colours. J Comp Physiol A. 1998;183:621–33.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Córdoba Zoo (Argentina) for their generous assistance and for allowing us to conduct part of this research in their facilities (Avian feed, etc.). This work is dedicated to the memory of Mr. Luis Ricardo Valdez for his invaluable assistance with the trap construction. D. J. Valdez and S. M. Benitez-Vieyra are researchers of CONICET. The study met Argentine legal requirements.

Funding

The corresponding author (Diego Javier Valdez) had no funding to cover this research; the entire work was made possible by the generous support of Córdoba Zoo, whose staff provided assistance in catching parakeets. PhDs Alicia Sércic and Andrea Cocucci from the Multidisciplinary Institute of Plant Biology (IMBIV-CONICET-UNC) generously lent the spectrophotometer. None of the persons and institutions mentioned above had grants for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM and DJG contributed equally to this paper. DJV conceived and designed the experiments. MM, DJG and DJV performed the experiments. MM, DJG, DJV and SMB-V analyzed the data. DJV contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. DJV and SMB-V wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the Guidelines for Ethical Research on Laboratory and Farm Animals and Wildlife Species and with the prior approval of the ethics committee of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) (Resolution No. 1047 ANNEXO II, 2005). The required permits were acquired from the Ministerio de Agua, Ambiente y Servicios Públicos of Córdoba, Argentina, through the Secretaría de Ambiente y Cambio Climático to capture specimens of Monk Parakeet for scientific purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Morales, M., Gigena, D.J., Benitez-Vieyra, S.M. et al. Subtle sexual plumage color dimorphism and size dimorphism in a South American colonial breeder, the Monk Parakeet (Myiopsitta monachus). Avian Res 11, 18 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-020-00204-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-020-00204-x