Abstract

Background

The ex vivo human perfused lung model has enabled optimizing donor lungs for transplantation and delineating mechanisms of lung injury. Perfusate and airspace biomarkers are a proxy of the lung response to experimental conditions. However, there is a lack of studies evaluating biomarker kinetics during perfusion and after exposure to stimuli. In this study, we analyzed the ex vivo-perfused lung response to three key perturbations: exposure to the perfusion circuit, exogenous fresh whole blood, and bacteria.

Results

Ninety-nine lungs rejected for transplantation underwent ex vivo perfusion. One hour after reaching experimental conditions, fresh whole blood was added to the perfusate (n = 55). Two hours after reaching target temperature, Streptococcus pneumoniae was added to the perfusate (n = 42) or to the airspaces (n = 17). Perfusate and airspace samples were collected at baseline (once lungs were equilibrated for 1 h, but before blood or bacteria were added) and 4 h later. Interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, angiopoietin (Ang)-2, and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (sTNFR)-1 were quantified. Baseline perfusate and airspace biomarker levels varied significantly, and this was not related to pre-procurement PaO2:FiO2 ratio, cold ischemia time, and baseline alveolar fluid clearance (AFC). After 4 h of ex vivo perfusion, the lung demonstrated a sustained production of proinflammatory mediators. The change in biomarker levels was not influenced by baseline donor lung characteristics (cold ischemia time, baseline AFC) nor was it associated with measures of experimental epithelial (final AFC) or endothelial (percent weight gain) injury. In the presence of exogenous blood, the rise in biomarkers was attenuated. Lungs exposed to intravenous (IV) bacteria relative to control lungs demonstrated a significantly higher rise in perfusate IL-6.

Conclusions

The ex vivo-perfused lung has a marked endogenous capacity to produce inflammatory mediators over the course of short-term perfusion that is not significantly influenced by donor lung characteristics or the presence of exogenous blood, and only minimally affected by the introduction of systemic bacteremia. The lack of association between biomarker change and donor lung cold ischemia time, final alveolar fluid clearance, and experimental percent weight gain suggests that the maintained ability of the human lung to produce biomarkers is not merely a marker of lung epithelial or endothelial injury, but may support the function of the lung as an immune cell reservoir.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The ex vivo human perfused lung has been used for nearly 70 years to study mechanisms of lung function [1]. The model facilitates characterizing biological mechanisms that may preserve the lung for transplantation as well as response to clinically relevant pathological conditions, such as exposure to endotoxin or bacteria [1,2,3]. The experimental preparation has improved the available pool of lungs appropriate for transplantation [4,5,6,7,8,9] and understanding mechanisms that contribute to primary graft dysfunction in lung transplant recipients [10]. It also offers insight into lung physiology in injury [11, 12] and as such, allows for the testing of new therapeutics (mesenchymal stem cells, microvesicles) [13,14,15,16].

The controlled conditions of the ex vivo-perfused lung make it possible to collect samples from multiple compartments (perfusate, lung tissue, airspaces) and to study the response to experimental intervention. The quantification of biomarkers in these compartments is representative of injury [17,18,19,20]. However, whether biomarker levels are associated with a negative outcome is uncertain in the ex vivo-perfused lung model because the rise in biomarkers does not always correlate with validated measures of lung function [21]. Furthermore, removing biomarkers thought to induce injury, such as IL-8, with an adsorbent membrane, does not improve lung function during prolonged ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) [22].

The uncertainty in the field prompted us to perform a detailed study of several clinically relevant biomarkers that have been studied in clinical samples as well as in ex vivo and in vitro models of lung injury. The four biomarkers include three biomarkers associated with inflammation: interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 (sTNFR1) [23,24,25], as well as one biomarker associated with endothelial activation: angiopoietin-2 (Ang-2) [25, 26].

Additionally, the human EVLP model has been shown to lack a response to the airspace administration of bacterial components (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) without the addition of exogenous blood [14]. Therefore, in many instances where the ex vivo human perfused lung model is used for studying the response to injurious stimuli, exogenous fresh human whole blood has been added to the perfusate [1, 15]. However, the influence of the addition fresh whole blood to the ex vivo human perfused lung on pro-inflammatory biomarker levels in the perfusate and in the airspaces has not been studied in detail.

The goal of our study was to address four important poorly understood concepts. First, do donor lung characteristics (PaO2:FiO2 ratio, cold ischemia time, baseline alveolar fluid clearance [3]) influence baseline biomarker levels or biomarker kinetics in the perfusate and airspaces? Second, what is the impact of exogenous fresh whole blood on biomarker kinetics in the perfusate and in the airspaces during EVLP? Third, what is the impact of exposure to bacteria (intravenous (IV) or airspace infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae) on perfusate and airspace biomarker kinetics relative to uninfected control lungs? Fourth, do donor lung characteristics influence relationships between biomarker kinetics in the presence of exogenous blood or after exposure to bacteria?

Results

Donor lung characteristics

A total of 99 single human lungs from 99 donors were studied under the following six experimental conditions: (1) control lungs with exogenous blood (n = 22), (2) intravenous infection with S. pneumoniae with exogenous blood (n = 19), (3) airspace infection with S. pneumoniae with exogenous blood (n = 14), (4) control lungs without exogenous blood (n = 18), (5) intravenous infection with S. pneumoniae without exogenous blood (n = 23), (6) airspace infection with S. pneumoniae without blood (n = 3). The baseline donor characteristics among the six experimental conditions were well balanced (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in donor age, organ cold ischemia time, PaO2:FiO2 ratio, and baseline alveolar fluid clearance (AFC). Among the lungs perfused without exogenous blood, a greater proportion of donors of control lungs relative to donors of lungs exposed to intravenous bacteria received pre-procurement antibiotics (89% vs 52%, p = 0.01). This imbalance in pre-procurement antibiotics was greater in control lungs and therefore would not be expected to affect bacterial proliferation.

Baseline biomarker variability and significant biomarker rise after 4 h of EVLP

Because the first sample was collected before the addition of experimental conditions (exogenous fresh whole blood, intravenous or airspace infection with S. pneumoniae), we were able to study baseline biomarker levels in the perfusate (n = 97) and in the airspace (n = 88). Baseline (time 0 h) perfusate and airspace samples collected 1 h after EVLP equilibration had a wide distribution in biomarker concentrations (Fig. 1).

Perfusate and airspace biomarker concentrations at baseline and after 4 h of ex vivo perfusion. Biomarker concentrations are presented on a Log10 scale. The capacity to produce the four inflammatory cytokines at the 4 hour relative to the 0-h time point in both the perfusate and in the airspace compartment was significant at p < 0.0001 for all presented data

Perfusate and airspace samples collected at baseline and after 4 h of EVLP were used to study biomarker kinetics. The ex vivo human perfused lung demonstrated a maintained capacity to produce inflammatory cytokines at 4 h relative to the 0-h time point in the perfusate and in the airspaces (Fig. 1) at a significance level of p < 0.0001. The substantial fold change in perfusate and airspace biomarkers is shown in sFigure 1.

A significant rise in the perfusate (sTable 1) and airspace (sTable 2) biomarkers was present in all six experimental conditions. This was especially true for IL-6 and IL-8 (sFigure 2A-B and sFigure 3A-B), with IL-6 levels increasing more than 200-fold (sFigure 1) up to a concentration of 1 μg/ml. The increase in perfusate and airspace sTNFR1 and Ang-2 was lower (sFigure 2C-D and sFigure 3C-D).

Donor characteristics and indicators of experimental lung injury are not associated with baseline biomarker levels and biomarker kinetics

Baseline biomarker levels were tested for their association with pre-procurement PaO2:FiO2 ratio, cold ischemia time, and baseline AFC. Neither perfusate nor airspace baseline biomarker concentrations were associated with these donor lung characteristics (Fig. 2a). The only exception was for airspace IL-6 and IL-8 levels, whereby a higher baseline AFC was associated with a higher baseline biomarker concentration (p < 0.0001).

Perfusate and airspace biomarkers at baseline and change after perfusion relative to lung characteristics. Associations between (a) baseline perfusate (n = 97) and airspace (n = 88) biomarker levels and donor lung characteristics, and (b) change in perfusate (n = 95) and airspace (n = 65) biomarker concentrations after 4 h of ex vivo lung perfusion and donor lung characteristics and indicators of lung epithelial and endothelial injuries at the end of the experiment. p values are presented after a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing

In spite of a substantial rise in perfusate and airspace IL-6 and IL-8, as well as to a lesser extent in sTNFR1 and Ang-2, there was no association between the change in any of the perfusate biomarker levels and indicators of lung injury at the end of the experiment (percent weight gain or final AFC) or baseline donor lung characteristics (Fig. 2b).

Exogenous blood attenuates perfusate IL-6 increase in lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae

The differences between perfusate and airspace biomarker kinetics after 4 h of ex vivo perfusion in the presence relative to the absence of fresh whole blood was compared in control lungs and in lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae (sTable 3). In control lungs, there were no statistically significant differences in the change in perfusate (Fig. 3a) or airspace (Fig. 3b) biomarkers after 4 hours of perfusion in lungs perfused with compared to without exogenous blood. In lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae, there was a significant difference in the increase in perfusate IL-6 (Fig. 3a) and airspace sTNFR1 (Fig. 3b) in lungs perfused with relative to without exogenous blood. In the absence of blood, perfusate IL-6 increase was 133,885 pg/ml higher relative to lungs perfused with blood (p = 0.003). In the presence of blood, airspace sTNFR1 increase was 1,793 pg/ml higher relative to lungs without blood (p = 0.009).

Impact of exogenous blood on biomarker change after 4 h of ex vivo lung perfusion. a Comparison of change in perfusate biomarker levels after 4 h of ex vivo perfusion in control lungs in the presence (n = 21) or in the absence (n = 17) of exogenous blood, and in IV S. pneumoniae exposed lungs in the presence (n = 19) or in the absence (n = 22) of exogenous blood. b Comparison of change in airspace biomarker levels after 4 h of ex vivo perfusion in control lungs in the presence (n = 16) or in the absence (n = 13) of exogenous blood, and in IV S. pneumoniae-exposed lungs in the presence (n = 13) or in the absence (n = 14) of exogenous blood

Adjustment for potential confounders (donor lung cold ischemia time and baseline AFC) in control lungs compared with lungs perfused with or without exogenous blood had minimal influence on perfusate and airspace biomarker kinetics (sTable 4). None of the significant biomarker kinetics discussed above were changed after adjustment.

IV S. pneumoniae contributes to an increase in perfusate IL-6 in the absence of exogenous blood

To address the question of whether there would be a difference in the increase in lung endogenous biomarker production after S. pneumonia exposure relative to control lungs, we studied (1) control lungs relative to lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae with exogenous blood, (2) control lungs relative to lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae without blood, and (3) control lungs relative to lungs exposed to airspace S. pneumoniae with exogenous blood (sTable 5).

Lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae perfused without exogenous blood relative to control lungs had a significantly greater increase in perfusate IL-6 (higher by 92,741 pg/ml, p = 0.04) and perfusate IL-8 (higher by 103,915 pg/ml, p = 0.05) (Fig. 4a). There were no differences in airspace biomarker levels (Fig. 4b). When exogenous blood was present in the model, lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae relative to control lungs had a greater increase in perfusate sTNFR1 (higher by 967 pg/ml, p = 0.04) (Fig. 4a), airspace sTNFR1 (higher by 1,492 pg/ml, p = 0.02), and airspace Ang-2 (higher by 823 pg/ml, p = 0.05) (Fig. 4b). In lungs exposed to airspace S. pneumoniae relative to control lungs, there was no significant difference between perfusate or airspace biomarker kinetics (sTable 5).

Impact of IV S. pneumoniae on biomarker change levels after ex vivo lung perfusion. a Comparison of change in perfusate biomarker levels after 4 h of ex vivo perfusion in control lungs (n = 17) relative to models with IV S. pneumoniae (n = 22) without blood and in control lungs (n = 21) relative to models with IV S. pneumoniae (n = 19) with blood. b Comparison of change in airspace biomarker levels after 4 h of ex vivo perfusion in control lungs (n = 13) relative to models with IV S. pneumoniae (n = 14) without blood and in control lungs (n = 16) relative to IV S. pneumoniae (n = 13) with blood

Adjustment for donor lung characteristics (cold ischemia time, baseline AFC, and pre-procurement antibiotics) in control lungs compared with lungs exposed to IV (sTable 6) and airspace (sTable 7) S. pneumoniae had minimal impact on perfusate and airspace biomarker kinetics. Furthermore, none of the significant biomarker kinetics were influenced by these adjustment variables.

Discussion

In the USA, lungs of approximately 75% eligible donors are ineligible for transplantation [27]. These lungs are an invaluable resource to study lung function and organ preservation to increase eligibility for transplantation. In this study, explanted human lungs rejected for transplantation underwent ex vivo lung perfusion and a detailed characterization of perfusate and airspace biomarker kinetics was performed under 6 experimental conditions.

During 4 h of EVLP, we found that the lung has a remarkable capacity to produce proteins associated with immune (IL-6, IL-8, sTNFR1) and endothelial (Ang-2) responses. The baseline level and the change in concentration of these mediators after 4 h of ex vivo perfusion was unrelated to the duration of cold ischemia time and parameters associated with deranged lung epithelial (alveolar fluid clearance) or endothelial (percent weight gain) function [1]. The lack of association between change in biomarker levels and the final AFC and percent weight gain suggests that the presence of very high levels of proinflammatory mediators does not result in deterioration of epithelial or endothelial barrier function. The weak but significant association between baseline AFC and the increase in airspace IL-6 and IL-8 levels, may suggest that lungs with higher baseline AFC have a higher rise in airspace concentrations of these two inflammatory markers. The addition of fresh whole blood attenuated the increase in perfusate IL-6 in lungs exposed to intravenous bacteria. The addition of a lethal dose of Gram-positive bacteria (S. pneumoniae) did not significantly change perfusate or airspace biomarker kinetics, with the exception of perfusate IL-6 in the absence of exogenous blood.

A similar high rise in some biomarkers quantified in this study has been demonstrated in prior reports of EVLP [20, 28]. IL-6 and IL-8 are inflammatory cytokines traditionally synonymous with organ injury and poor outcome. In the EVLP model, several studies of cross-sectional cytokine levels suggest that donor lung levels of these biomarkers are inversely associated with graft function in the transplant recipient [17,18,19,20]. Interestingly, cytokines in the EVLP perfusate of successfully transplanted lungs also reach extremely high levels (as much as a 30–100-fold increase in IL-6 and IL-8) without evidence of primary graft dysfunction (PGD) [20, 21]. If IL-6 and IL-8 are always injurious, why do not more transplant recipients develop PGD?

High levels of IL-6, IL-8, sTNFR1, and Ang-2 in plasma samples of patients with the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are well-known for their association with poor outcomes [29, 30]. However, plasma biomarker levels are substantially lower than those reported in EVLP perfusate. This discrepancy between the extremely high levels of inflammatory cytokines in the EVLP perfusate and the lack of injury in every transplant recipient as well as the lack of association with experimental measurements of injury in our study (percent weight gain, final AFC) suggest that these cytokines have an additional biologic significance [31], especially in the EVLP model. Future studies may provide insight into the biologic relevance of the elevated biomarker levels in the EVLP model, including their potential role in immune cell recruitment, enhancement of phagocytosis, stimulation of tissue turnover, or eradication of pathogens.

The source of biomarker production and the mechanism of accumulation are uncertain. The EVLP model lacks mechanisms associated with clearance, specifically the liver [32], the kidneys [33], and components of the vascular compartment, the absence of which may explain the striking difference between biomarker concentrations detectable in plasma relative to the perfusate and airspaces of the ex vivo perfused lung. In our experiments in which only 100 ml of fresh whole blood was added to 2 l of EVLP perfusate (representative of a hematocrit of approximately 2%), there appeared to be a trend toward a dampening effect on the increase in perfusate IL-6 and IL-8 levels in control lungs as well as in lungs exposed to IV S. pneumoniae. This suggests that protective factors are present in blood that either reduce the production of these cytokines, that increase their enzymatic clearance, or that facilitate their sequestration [34]. Future investigation of whole blood components that may be responsible for the decrease in inflammatory biomarker levels may be relevant to transplantation as several studies support the notion that high IL-8 in perfusate is related to an increased incidence of PGD3 in the recipient [17,18,19].

A potential source of cytokines may be cell necrosis and apoptosis due to ischemia-reperfusion injury [35]. However, neither the baseline nor the change in biomarkers after 4 h of EVLP was associated with cold ischemia time, suggesting that presumed cell necrosis and apoptosis cannot on their own explain the high abundance of cytokines in our model. In fact, prolonged hypothermia without reperfusion did not increase pneumocyte apoptosis in a rat lung transplant model [36]. Also, there is evidence from studying tissue biomarker levels in the human EVLP model that inflammatory cytokine levels do not significantly differ after extended cold ischemia time [7].

Of note, not all biomarker levels increased to the same extent during EVLP. The small change in Ang-2 levels during the 4 h of ex vivo perfusion relative to inflammatory biomarker levels is puzzling. This protein is produced by the endothelium and is stored in Weibel Palade bodies [26], where it has a long half-life (over 18 h) and can be secreted within minutes of stimulation [37]. However, despite lung injury due to ischemia-reperfusion and addition of lethal doses of S. pneumoniae, the magnitude of Ang-2 change was minimal compared with the change in IL-6 and IL-8.

The observation that starting AFC is only significantly associated with baseline IL-6 and IL-8 levels in the airspace compartment is intriguing. It is plausible that when the lung epithelial function is intact and alveolar fluid clearance is preserved [38], IL-6 and IL-8 may concentrate in the airspaces. It also implies that when interpreting levels of these cytokines in the airspace compartment of the EVLP model, it is important to measure and account for lung alveolar fluid clearance.

This study has some limitations. First, only two time points were studied during the course of perfusion, and as such, it is possible we missed important time point biomarker production trends, particularly in experimental conditions in the presence of bacteria. It is also possible that the perfusion was not long enough to appreciate differences between the experimental conditions included in this study. Secondly, we studied only four soluble proteins, and to detect relevant differences between experimental conditions, other proteins may need to be studied. It is also plausible that other metrics, such as RNA expression, microvesicle or lipid production, could provide insight into biological differences between the experimental conditions. Third, our experiments were performed with a single bacterial pathogen, and as such, the data may not be extrapolated to infection with other pathogens. Lastly, the effect of exogenous whole blood on biomarker kinetics in lungs exposed to airspace S. pneumoniae could not be studied as there were only 3 lungs in this subgroup. Therefore, the previous observation that the addition of whole blood leads to a sharp increase in airspace biomarkers (IL-1β, TNF⍺, and IL-8) when a bacterial component (LPS) is instilled into one of the lung lobes [14] could not be ascertained.

Conclusions

Overall, the ex vivo-perfused lung has a remarkable capacity to generate high levels of inflammatory proteins during 4 h of perfusion. This was true in all experimental conditions, including control lungs, suggesting that future EVLP models assessing effect of injury or novel therapies should incorporate appropriate control lungs in the study design. The substantial increase in biomarker levels between the two time points suggests that future studies of cross-sectional and longitudinal biomarker analysis should ensure strict adherence to predefined timing of sample collection. The addition of blood does not increase biomarker levels, while the addition of live bacteria results in a higher rise in only IL-6 in lungs perfused without exogenous blood. The remarkable lack of association between baseline proinflammatory biomarker levels as well as their increase over time and donor lung characteristics (cold ischemia time, starting AFC) and experimental outcomes (alveolar fluid clearance 5 h after perfusion and the percent weight gain) suggests that the maintained ability to produce biomarkers is not merely a marker of lung epithelial or endothelial injury and may instead support the lung’s role as an immune reservoir.

Materials and methods

Ex vivo human perfused lung

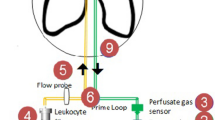

Donor lungs rejected for transplantation were received from Donor Network West. Lungs were rejected for various reasons, including a mismatch in sex, race, size, or geography between the donor and available recipients, donor age or smoking history, radiographic or bronchoscopic findings suggestive of atelectasis, edema and/or infection, or other elements of the donor history or clinical course [39, 40]. The right or left lung was selected for EVLP based on gross appearance, as previously described [1]. Briefly, the main bronchus was intubated with an endotracheal tube and the pulmonary artery was cannulated. The lung was perfused with 2 l of acellular DME-H21 media with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and warmed to 37 °C. Subsequently, 8 cm H2O of continuous positive airway pressure was applied using room air. Lung weight was obtained at the start (baseline) and at the end of each experiment. One hour after experimental conditions were reached, 100 ml of exogenous fresh whole blood was added to the perfusate of some of the lungs (sFigure 4). University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained for the collection of blood from healthy volunteers (laboratory members).

Quantification of lung function: alveolar fluid clearance

Alveolar fluid clearance (AFC) was determined once the ex vivo-perfused lung was equilibrated on the circuit by introducing 100 ml of normal saline with 5% BSA into the distal airspaces. Samples for measurement of total protein by refractometry were collected at 5 and 35 min via a catheter inserted into the endobronchial tube. AFC was calculated using the formula: AFC (%/h) = 2(1 − Ci/Cf), where Ci is the 5-min sample protein concentration and Cf is the 35-min sample protein concentration [3, 41]. The AFC for all experiments was calculated at the start of the experiment (baseline) and at 5 h (sFigure 4).

Infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae

S. pneumoniae serotype 19F (49619; ATCC, Manassas, VA) was grown in brain-heart broth (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks MD), and 1010 bacteria was resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline for administration according to a weight-based adjustment of a severe pneumonia murine model [42, 43]. Two hours after reaching target temperature, bacteria were added intravenously into the perfusate (non-pulmonary sepsis model) or into the airspaces (pneumonia model, sFigure 4).

Biomarker quantification

Perfusate and airspace samples were prospectively collected for biomarker quantification at two time points. The first sample was collected after the lungs were equilibrated on the circuit for 1 h (immediately prior to the addition of exogenous whole blood and 1 h prior to the introduction of S. pneumoniae in selected experiments; sample referred to as time 0 h). The second sample was collected 4 h later (sample referred to as time 4 h, sFigure 4). Airspace fluid samples were not available for 11 lungs at the 0-h timepoint and 24 lungs at the 4-h time. This was due to mucus production or very effective AFC which prevented airspace fluid collection. For lungs perfused with exogenous fresh whole blood, this corresponded to a 4-h exposure to blood. For lungs exposed to S. pneumoniae, this corresponded to a 3-h exposure to bacteria. All samples were cryopreserved at − 80 °C prior to protein quantification using the Simple PlexTM Ella multiplex microfluidic platform (Protein Simple, CA, USA). A 4-plex custom panel was used to quantify interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, angiopoietin (Ang)-2, and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (sTNFR)-1. Low-abundance proteins (Ang-2) were tested at a 1:10 dilution, and high-abundance proteins (IL-6, IL-8, sTNFR-1) were tested at a 1:1000 dilution. The same dilutions were used for perfusate and airspace samples. Assays were performed according to manufacturer’s protocol, as described previously [44]. Raw data were analyzed using the SimplePlex Explorer software.

Statistical analysis

Relationships between continuous variables were performed using Pearson (normally distributed data) or Spearman (skewed data) correlation, with a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Comparison of baseline continuous variables among experimental groups were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test and dichotomous variables were compared using the chi squared test. Comparisons of biomarker kinetics among experimental conditions were made using generalized estimating equation models (GEE) using robust standard errors [45]. Lungs lacking a sample at the second time point (t4h) were excluded from analysis. The analyses included (1) impact of exogenous whole fresh blood on change in perfusate and airspace biomarker levels in lung subgroups stratified by exposure to bacteria (control/no bacteria, intravenous bacteria), (2) impact of addition of intravenous S. pneumoniae (non-pulmonary sepsis model) on change in perfusate and airspace biomarker levels in lung subgroups stratified by addition of exogenous whole fresh blood, and (3) impact of addition of airspace S. pneumoniae (pneumonia model) on change in perfusate and airspace biomarker levels in lungs perfused with exogenous whole fresh blood. Too few lungs exposed to airspace S. pneumoniae were perfused without exogenous blood (n = 3) to test the impact of airspace bacteria on biomarker kinetics in this experimental subgroup. Interaction terms for cold ischemia time, baseline lung function (the surrogate of which was baseline AFC), lung response at end of experiment (AFC at 5 h, percent weight gain) were included individually in the above GEE models to test for the effect of these potential confounders on perfusate and airspace biomarker kinetics. In models assessing the impact of bacteria on biomarker kinetics, an interaction term for the administration of pre-procurement antibiotics was included. Statistical analyses and data presentation were performed using STATA v14.1 (StataCorp 2015).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IL-6 :

-

Interleukin-6

- IL-8:

-

Interleukin-8

- Ang-2 :

-

Angiopoietin-2

- sTNFR1:

-

Soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor-1

- AFC:

-

Alveolar fluid clearance

- IV:

-

Intravenous

- EVLP:

-

Ex vivo lung perfusion

- S. pneumoniae :

-

Streptococcus pneumoniae

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

References

Ross JT, Nesseler N, Lee JW, Ware LB, Matthay MA (2019) The ex vivo human lung: research value for translational science. JCI Insight 4(11):e128833

Ware LB, Wang Y, Fang X, Warnock M, Sakuma T, Hall TS, Matthay M (2002) Assessment of lungs rejected for transplantation and implications for donor selection. Lancet 360:619–620

Frank JA, Briot R, Lee JW, Ishizaka A, Uchida T, Matthay MA (2007) Physiological and biochemical markers of alveolar epithelial barrier dysfunction in human perfused lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293:L52–L59

Fisher A, Andreasson A, Chrysos A, Lally J, Mamasoula C, Exley C, Wilkinson J, Qian J, Watson G, Lewington O, Chadwick T, McColl E, Pearce M, Mann K, McMeekin N, Vale L, Tsui S, Yonan N, Simon A, Marczin N, Mascaro J, Dark J (2016) An observational study of Donor Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion in UK lung transplantation: DEVELOP-UK. Health Technol Assess 20:1–276

Cypel M, Yeung JC, Liu M, Anraku M, Chen F, Karolak W, Sato M, Laratta J, Azad S, Madonik M, Chow CW, Chaparro C, Hutcheon M, Singer LG, Slutsky AS, Yasufuku K, de Perrot M, Pierre AF, Waddell TK, Keshavjee S (2011) Normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion in clinical lung transplantation. N Engl J Med 364:1431–1440

Koike T, Yeung JC, Cypel M, Rubacha M, Matsuda Y, Sato M, Waddell TK, Liu M, Keshavjee S (2011) Kinetics of lactate metabolism during acellular normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion. J Heart Lung Transplant 30:1312–1319

Hsin M, Au T (2018) Ex vivo lung perfusion: a potential platform for molecular diagnosis and ex vivo organ repair. J Thorac Dis 10:S1871–S1883

Boffini M, Ricci D, Barbero C, Bonato R, Ribezzo M, Mancuso E, Attisani M, Simonato E, Magistroni P, Mansouri M, Solidoro P, Baldi S, Pasero D, Amoroso A, Rinaldi M (2013) Ex vivo lung perfusion increases the pool of lung grafts: analysis of its potential and real impact on a lung transplant program. Transplant Proc 45:2624–2626

Sage E, Mussot S, Trebbia G, Puyo P, Stern M, Dartevelle P, Chapelier A, Fischler M, Foch Lung Transplant G (2014) Lung transplantation from initially rejected donors after ex vivo lung reconditioning: the French experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 46:794–799

Tatham KC, O'Dea KP, Wakabayashi K, Marczin N, Takata M (2015) The role of ex vivo lung perfusion in lung transplantation. J Intensive Care Soc 16:58–63

Shaver CM, Wickersham N, McNeil JB, Nagata H, Miller A, Landstreet SR, Kuck JL, Diamond JM, Lederer DJ, Kawut SM, Palmer SM, Wille KM, Weinacker A, Lama VN, Crespo MM, Orens JB, Shah PD, Hage CA, Cantu E 3rd, Porteous MK, Dhillon G, McDyer J, Bastarache JA, Christie JD, Ware LB, Lung Transplant Outcomes G (2018) Cell-free hemoglobin promotes primary graft dysfunction through oxidative lung endothelial injury. JCI Insight 3(2):e98546

Ross JT, Nesseler N, Leligdowicz A, Zemans RL, Mahida RY, Minus E, Langelier C, Gotts JE, Matthay MA (2020) The ex vivo human perfused lung is resistant to injury by high-dose S. pneumoniae bacteremia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 319:L218–L227

Liu A, Park JH, Zhang X, Sugita S, Naito Y, Lee JH, Kato H, Hao Q, Matthay MA, Lee JW (2019) Therapeutic effects of hyaluronic acid in bacterial pneumonia in ex vivo human perfused lungs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 200:1234–1245

Lee JW, Fang X, Gupta N, Serikov V, Matthay MA (2009) Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of E. coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in the ex vivo human perfused lung. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:16357–16362

Lee JW, Krasnodembskaya A, McKenna DH, Song Y, Abbott J, Matthay MA (2013) Therapeutic effects of human mesenchymal stem cells in ex vivo human lungs injured with live bacteria. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187:751–760

Weathington NM, Alvarez D, Sembrat J, Radder J, Cardenes N, Noda K, Gong Q, Wong H, Kolls J, D'Cunha J, Mallampalli RK, Chen BB, Rojas M (2018) Ex vivo lung perfusion as a human platform for preclinical small molecule testing. JCI Insight 3(19):e95515 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6237445/

De Perrot M, Sekine Y, Fischer S, Waddell TK, McRae K, Liu M, Wigle DA, Keshavjee S (2002) Interleukin-8 release during early reperfusion predicts graft function in human lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:211–215

Fisher AJ, Donnelly SC, Hirani N, Haslett C, Strieter RM, Dark JH, Corris PA (2001) Elevated levels of interleukin-8 in donor lungs is associated with early graft failure after lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163:259–265

Saito T, Takahashi H, Kaneda H, Binnie M, Azad S, Sato M, Waddell TK, Cypel M, Liu M, Keshavjee S (2013) Impact of cytokine expression in the pre-implanted donor lung on the development of chronic lung allograft dysfunction subtypes. Am J Transplant 13:3192–3201

Machuca TN, Cypel M, Yeung JC, Bonato R, Zamel R, Chen M, Azad S, Hsin MK, Saito T, Guan Z, Waddell TK, Liu M, Keshavjee S (2015) Protein expression profiling predicts graft performance in clinical ex vivo lung perfusion. Ann Surg 261:591–597

Sadaria MR, Smith PD, Fullerton DA, Justison GA, Lee JH, Puskas F, Grover FL, Cleveland JC Jr, Reece TB, Weyant MJ (2011) Cytokine expression profile in human lungs undergoing normothermic ex-vivo lung perfusion. Ann Thorac Surg 92:478–484

Kakishita T, Oto T, Hori S, Miyoshi K, Otani S, Yamamoto S, Waki N, Yoshida O, Okazaki M, Yamane M, Toyooka S, Sano Y, Miyoshi S (2010) Suppression of inflammatory cytokines during ex vivo lung perfusion with an adsorbent membrane. Ann Thorac Surg 89:1773–1779

Turner MD, Nedjai B, Hurst T, Pennington DJ (2014) Cytokines and chemokines: at the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1843:2563–2582

Parsons PE, Matthay MA, Ware LB, Eisner MD, National Heart LBIARDSCTN (2005) Elevated plasma levels of soluble TNF receptors are associated with morbidity and mortality in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288:L426–L431

Hendrickson CM, Matthay MA (2018) Endothelial biomarkers in human sepsis: pathogenesis and prognosis for ARDS. Pulm Circ 8:2045894018769876

Leligdowicz A, Richard-Greenblatt M, Wright J, Crowley VM, Kain KC (2018) Endothelial activation: the Ang/Tie axis in sepsis. Front Immunol 9:838

Valapour M, Lehr CJ, Skeans MA, Smith JM, Carrico R, Uccellini K, Lehman R, Robinson A, Israni AK, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL (2018) OPTN/SRTR 2016 annual data report: lung. Am J Transplant 18(Suppl 1):363–433

Andreasson AS, Karamanou DM, Gillespie CS, Ozalp F, Butt T, Hill P, Jiwa K, Walden HR, Green NJ, Borthwick LA, Clark SC, Pauli H, Gould KF, Corris PA, Ali S, Dark JH, Fisher AJ (2017) Profiling inflammation and tissue injury markers in perfusate and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid during human ex vivo lung perfusion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 51:577–586

Parsons PE, Eisner MD, Thompson BT, Matthay MA, Ancukiewicz M, Bernard GR, Wheeler AP, Network NARDSCT (2005) Lower tidal volume ventilation and plasma cytokine markers of inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 33:1–6 discussion 230-232

Calfee CS, Ware LB, Glidden DV, Eisner MD, Parsons PE, Thompson BT, Matthay MA, National Heart B, Lung Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome N (2011) Use of risk reclassification with multiple biomarkers improves mortality prediction in acute lung injury. Crit Care Med 39:711–717

Tarrant JM (2010) Blood cytokines as biomarkers of in vivo toxicity in preclinical safety assessment: considerations for their use. Toxicol Sci 117:4–16

Zhou Z, Xu MJ, Gao B (2016) Hepatocytes: a key cell type for innate immunity. Cell Mol Immunol 13:301–315

Andres-Hernando A, Dursun B, Altmann C, Ahuja N, He Z, Bhargava R, Edelstein CE, Jani A, Hoke TS, Klein C, Faubel S (2012) Cytokine production increases and cytokine clearance decreases in mice with bilateral nephrectomy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27:4339–4347

Darbonne WC, Rice GC, Mohler MA, Apple T, Hebert CA, Valente AJ, Baker JB (1991) Red blood cells are a sink for interleukin 8, a leukocyte chemotaxin. J Clin Invest 88:1362–1369

Ng CS, Wan S, Yim AP (2005) Pulmonary ischaemia-reperfusion injury: role of apoptosis. Eur Respir J 25:356–363

Stammberger U, Gaspert A, Hillinger S, Vogt P, Odermatt B, Weder W, Schmid RA (2000) Apoptosis induced by ischemia and reperfusion in experimental lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg 69:1532–1536

Fiedler U, Scharpfenecker M, Koidl S, Hegen A, Grunow V, Schmidt JM, Kriz W, Thurston G, Augustin HG (2004) The Tie-2 ligand angiopoietin-2 is stored in and rapidly released upon stimulation from endothelial cell Weibel-Palade bodies. Blood 103:4150–4156

Hastings RH, Folkesson HG, Matthay MA (2004) Mechanisms of alveolar protein clearance in the intact lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 286:L679–L689

Chaney J, Suzuki Y, Cantu E 3rd, van Berkel V (2014) Lung donor selection criteria. J Thorac Dis 6:1032–1038

Kukreja J, Chen J, Brzezinski M (2020) Redefining marginality: donor lung criteria. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 25:280–284

Matthay MA (2014) Resolution of pulmonary edema. Thirty years of progress. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 189:1301–1308

Gotts JE, Chun L, Abbott J, Fang X, Takasaka N, Nishimura SL, Springer ML, Schick SF, Calfee CS, Matthay MA (2018) Cigarette smoke exposure worsens acute lung injury in antibiotic-treated bacterial pneumonia in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315:L25–L40

Gotts JE, Bernard O, Chun L, Croze RH, Ross JT, Nesseler N, Wu X, Abbott J, Fang X, Calfee CS, Matthay MA (2019) Clinically relevant model of pneumococcal pneumonia, ARDS, and non-pulmonary organ dysfunction in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 317:L717-L736

Leligdowicz A, Conroy AL, Hawkes M, Zhong K, Lebovic G, Matthay MA, Kain KC (2017) Validation of two multiplex platforms to quantify circulating markers of inflammation and endothelial injury in severe infection. PloS One 12:e0175130

Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE (2012) Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. Springer, New York

Acknowledgements

We thank donor families for their gift to research and Donor Network West for assistance in obtaining human lungs for research.

Funding

Dr. Leligdowicz was supported by the CIHR Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship and the University of Toronto Clinician Scientist Training Program (CSTP); Dr. Ross by NIH T32DK007573-23, Dr. Nesseler by research grants from the Société Française d’Anesthésie-Réanimation (SFAR, Paris, France), the Association Chirurgicale pour le Développement et l’Amélioration des Techniques de Dépistage de Traitement des Maladies Cardiovasculaires (ADETEC, Paris, France), and the Journées Rennaises d’Anesthésie-Réanimation (JRAR) association (Rennes, France); and Dr. Matthay by NHLBI HL140026, HL51856, HL134828, and UCSF Nina Ireland Fund. None of the funding bodies had a role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AL designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and prepared the manuscript; JTR designed the study, performed the experiments, and revised the manuscript; NN designed the study and performed the experiments; MAM designed the study, interpreted the data, and revised the final manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Explicit approval for the use of donor lungs for research was sought from each donor’s family by Donor Network West.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Figures and Tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leligdowicz, A., Ross, J.T., Nesseler, N. et al. The endogenous capacity to produce proinflammatory mediators by the ex vivo human perfused lung. ICMx 8, 56 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-020-00343-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-020-00343-x