Abstract

Purpose

Gait independence is one of the most important factors related to returning home from the hospital for patients treated in the intensive care unit (ICU), but the factors affecting gait independence have not been clarified. This study aimed to determine the factors affecting gait independence at hospital discharge using a standardized early mobilization protocol that was shared by participating hospitals.

Materials and methods

Patients who entered the ICU from January 2017 to March 2018 were screened. The exclusion criteria were mechanical ventilation < 48 hours, age < 18, loss of gait independence before hospitalization, being treated for neurological issues, unrecoverable disease, unavailability of continuous data, and death during ICU stay. Basic attributes, such as age, ICU length of stay, information on early mobilization while in the ICU, Medical Research Council (MRC) sum-score at ICU discharge, incidence of ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) and delirium, and the degree of gait independence at hospital discharge, were collected. Gait independence was determined using a mobility scale of the Barthel Index, and the factors that impaired gait independence at hospital discharge were investigated using a Cox proportional hazard regression analysis.

Results

One hundred thirty-two patients were analyzed. In the univariate analysis, age, APACHE II score, duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay, incidence of delirium, and MRC sum-score at ICU discharge were extracted as significant. In the multivariate analysis, age (p = 0.014), MRC sum-score < 48 (p = 0.021), and delirium at discharge from ICU (p < 0.0001) were extracted as significant variables.

Conclusions

We found that age and incidence of ICU-AW and delirium were significantly related to impaired gait independence at hospital discharge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in intensive care have led to a paradigm shift of the treatment goal from “saving life” to “returning home with full physical and mental recovery.” Patients treated with mechanical ventilation and sedation in the intensive care unit (ICU) face increased risks of functional disorders and impaired mobility as a result of disuse syndrome [1] and require prolonged rehabilitation [2]. Several studies have shown that early mobilization provides better quality of life after ICU discharge [3,4,5]. Contrarily, muscle weakness developed during hospitalization, the so-called ICU-acquired weakness (AW), and delirium are factors that reduce the quality of life after discharge and delay resocialization. In addition, it is reported that the incidence of ICU-AW and delirium not only prolonged the duration of mechanical ventilation and length of ICU stay, but also impaired general activities of daily living including gait and cognitive function [6,7,8,9]. The American Thoracic Society and American College of Chest Physicians published clinical practice guidelines that recommend interventions to achieve early mobilization in patients who expected more than 24 h of mechanical ventilation [10]. Early mobilization carried out with a clear protocol provided functional independence, including gait, as a goal of ICU rehabilitation [9, 11, 12].

However, effective ICU rehabilitation leading to improved home discharge rates is still unclear. Gait independence is considered one of the most important factors related to returning home for patients treated in the ICU [5, 13]. Although effective early mobilization on achieving gait independence has been reported in a few studies [5, 14,15,16,17], the factors that affect gait independence at hospital discharge have not been investigated. We established a multicenter research group 3 years ago to explore the effective early mobilization protocol. We shared the previously published standardized protocol among the eight participating hospitals. We found, however, a considerable number of patients had impaired gait independence at hospital discharge. To further improve early mobilization protocol (Appendix 1), it is essential to determine risk factors responsible for losing gait independence and to provide countermeasures.

The purpose of the study is to assess the data of the participating hospitals retrospectively and seek the potential factors associated with gait dependence at hospital discharge. We hypothesized that incidence of ICU-AW and delirium may be negatively associated with gait independence as demonstrated above.

Methods

Study design and subject

We reviewed medical records of the patients treated in the ICU between January 2017 and March 2018 in eight tertiary hospitals in Japan. Patients who were mechanically ventilated for equal to or more than 48 h in the ICU were screened. Patients with ages less than 18 years, loss of gait independence before hospitalization [18], being treated for neurological issues, unrecoverable disease, unavailability of continuous data, and death during ICU stay were excluded from the study. Patients requiring wheelchair or other gait assistance except a walking stick before admission were excluded.

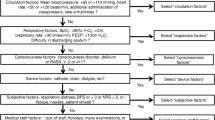

The number of ICU beds in each hospital is shown in Appendix 2. Protocols for sedation, analgesia, and weaning were not shared. However, the protocol for rehabilitation used in the previous study [19] was shared in the participating hospitals, and ICU staff members were trained and fully compliant with the protocol. The start and cancelation criteria of the protocol are shown in Appendix 1. Before starting the current study, the participating hospitals had a 6-month preparation period to carry out the early mobilization study protocol and data collection for the standardization of the quantity (frequency) and quality of intervention. All patients were provided the usual rehabilitation sessions on a continuous basis only by physical or occupational therapists after ICU discharge.

Each participating hospital obtained approval of the study by the respective ethics committee (the Nagoya Medical Center Hospital Institutional Review Board; approval number: 2018-19).

Date collection

We collected detailed information at initial hospitalization and ICU discharge. We also collected data regarding independent gait ability upon hospital discharge. All data were obtained as a usual clinical practice.

Information at admission included age, sex, body weight, body mass index (BMI), main cause of ICU admission, Charlson’s Comorbidity Index (CCI) [20], Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score [21], and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [22]. Data during ICU stay included the time to first rehabilitation assessment, duration of mechanical ventilation, time to first out-of-bed mobilization, and highest score achieved on the ICU-mobility scale (IMS) [23]. We also investigated the incidence of adverse events during rehabilitation, such as cardiopulmonary arrest, fall to knees or the ground, inadvertent removal of medical devices, desaturation (< 90%) or more than 10% decrease from the baseline, bradypnea (< 5 breaths/min), tachypnea (> 40 breaths/min), bradycardia (< 40 beats/min), tachycardia (> 130 beats/min), hypotension (systolic blood pressure [SBP] < 80 mmHg), hypertension (SBP > 200 mmHg), and newly occurring arrhythmia. At ICU discharge, we collected incidence of ICU-acquired weakness (ICU-AW) and delirium, respectively. As mentioned above, early mobilization was performed according to the previous protocol [19] consisted with five session levels (see Appendix 1). We investigated the number of times levels 3, 4, and 5 were achieved, and total number of times levels higher than level 2 were achieved. We calculated ICU length of stay at ICU discharge, and hospital length of stay and ratio of home discharge at hospital discharge.

The IMS provides a quick and simple bedside method of measuring the mobility of a critically ill patient. As functional endpoints in studies of rehabilitation in the ICU, the IMS provides a sensitive 11-point ordinal scale, ranging from nothing (lying/passive exercises in bed, score of 0) to independent ambulation (score of 10). ICU-AW was evaluated using Medical Research Council (MRC) sum-score by the responsible physical therapist, and a value of less than 48 was defined as having developed an ICU-AW [24, 25]. The cooperation-level assessment was carried out, and muscle strength tests were only performed when the subject correctly answered the five questions [26]. For the assessment of delirium, either the delirium screening tool of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) [27] or the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) [28] was used according to the usual practice of each participating hospital. Outcomes other than home discharge included transfers to rehabilitation hospitals and to nursing homes.

Patients who could walk 45 m or more with or without braces were determined as gait independent. We also used mobility scale of the Barthel Index (BI) to quantitatively assess gait independence [18, 29]. BI is the most widely used ADL scale, and its reliability and relevance have been recognized [30]. Because we previously determined BI was an effective mobility parameter to assess the achievement of gait independence [31], we used this parameter in the current study. BI was measured at ICU and hospital discharge.

Statistical analysis

We compared the basic attributes and rehabilitation progress factors expressed by the median (interquartile range) or the number of cases (%) in the data in both groups. The Mann-Whitney test was used for intergroup comparisons of the continuous and ordinal variables of each item, and the intergroup comparison of the nominal variables was examined using the χ2 test. For the multivariate analysis, we used gait independence at discharge as the dependent variable, and the explanatory variables were the items other than the variables of measurement at discharge. A Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used, in which all items with p < 0.05 in a univariate analysis were input into the multivariate model. We assessed the probability of gait independence at hospital discharge as a function of the interval from ICU discharge to hospital discharge using the Kaplan-Meier curve. JMP version 13.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The significance level was less than 5%.

Results

During the study period, 1803 patients were screened and 269 patients were included in the study. Thirty-five died during hospitalization, and 102 patients were lost during follow-up period. Finally, 132 patients were discharged. MRC sum-score at ICU discharge was measured in all these patients (Fig. 1). Independent gait at hospital discharge was observed in 84 patients (independence group), but not in 48 patients (dependence group). Table 1 shows the demographic data of the patients in the total, independence, and dependence group. In the comparison of both groups, there was a significant difference in age (p < .0001).

Table 2 shows a comparison of clinical outcomes during hospitalization. The independence group showed a significant decrease in the length of ICU stays (p = 0.025), MRC sum-score < 48, and delirium at ICU discharge (p < .0001) compared to the dependence group. The home discharge ratio in the independence group was significantly higher compared to that in the dependence group (p < .0001). There were no significant differences in the duration of mechanical ventilation; the time to first out-of-bed mobilization; the mobility status, such as the highest IMS; the hospital length of stay; or the incidence of adverse events. Sixty-six out of 132 patients (50%) had ICU-AW at ICU discharge. Supplemental data are shown in Appendix 3.

Table 3 shows the results of univariate and multivariate analysis performed to identify potential factors for gait independence. In the univariate analysis, age, APACHE II score, ICU length of stay, incidence of delirium, and MRC sum-score at ICU discharge were extracted as significant. In the multivariate analysis, age, incidence of MRC sum-score < 48, and delirium at discharge from ICU were extracted as significant variables. The Kaplan-Meier curve to show the probability of gait independence from ICU discharge is presented in Fig. 2.

Discussion

In this study, we retrospectively investigated the factors affecting gait independence at hospital discharge in the ICUs of eight different hospitals sharing the early mobilization protocol. To correctly use the protocol among the hospitals, we set up a preparation period prior to the study. We confirmed ICU-AW developed in half of the patients and was significantly related to gait independence at hospital discharge as well as age and delirium.

Previous studies have reported disease severity, complications, and duration of mechanical ventilation were associated with gait independence at hospital discharge [32, 33]. Another study has reported that the main risk factors for ICU-AW include high severity of illness upon admission, sepsis, multiple organ failure, prolonged immobilization, hyperglycemia, and age [34]. Therefore, we expected disease severity and duration of mechanical ventilation to be a determinant of gait independence. However, no physiological severity parameters, except age, were included in the results. One possible reason is that aforementioned studies were conducted without the standardized early mobilization protocol. It is suggested that the application of an appropriate protocol for early mobilization is key for the contribution of disease severity and duration of mechanical ventilation to gait independence.

Both ICU-AW and delirium affect not only mortality but also health-related quality of life and increase ICU length of stay [35,36,37,38,39]. Deep sedation is associated with ICU-AW and delirium [40, 41]. Additionally, there is considerable evidence that early mobilization can decrease the incidence of ICU-AW and delirium [40,41,42]. In this study, however, we started mobilization sessions as early as the third ICU-day according to our early mobilization protocol and found that ICU-AW and delirium occurred in 50% and 35.4% of the patients at ICU discharge, respectively. This incidence was comparable to previous studies [43, 44]. In the ICU setting, pain, discomfort, delirium, immobility, and sleep are problems, and it is recommended to carry out early mobilization under appropriate analgesia and sedation management [45]. A single-center randomized controlled study reported the failure of early mobilization in the reduction of ICU stay, ventilator days, or preservation of muscle strength [46], and the lack of a clear sedation protocol possibly contributed to the results [47]. The lack of a sedation protocol caused a similar situation in our study, another consequence of early mobilization. To increase MRC sum-score at ICU discharge, it is suggested to introduce new rehabilitation program which could be performed on the bed during levels 1 and 2 such as electrical muscle stimulation [48] because it can be implemented even when the patient can afford passive exercise only. To reduce delirium, it is suggested that a comprehensive management system that includes uniform protocols of sedation, analgesics, and mechanical ventilation withdrawal is shared as a standard care among the participating facilities.

The average ICU length of stay was 8 days. Consequently, out-of-bed mobilization could be provided on average only once or twice during the ICU stay. On the other hand, the median length of hospitalization was 40 days. Because the criteria for hospital discharge are different among the facilities, this factor could have some influence on gait independence. However, there was no significant difference between hospital length of stay and gait independence. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the distribution of hospital days and the ratio of gait independence. Taken together, the association of gait independence with hospital length of stay was limited. On the other hand, the home discharge rate was significantly higher in the independence group. The factors age, decreasing delirium, and MRC sum-score more than 48 will become important indicators as a major goal of rehabilitation.

This study has several limitations. First, we shared a well-defined protocol for early mobilization but not for sedation, analgesia, and weaning from mechanical ventilation. We could not perfectly collect the data on medication [49], such as the type of muscle relaxant or vasopressor prescribed, the cumulative dose used, and the use of glucocorticoids, which are associated with ICU-AW. Also, we did not investigate the effects of the invasive treatments in the ICU that can make the patient bedridden (continuous renal replacement therapy, veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, intra-aortic balloon pumping, etc.) and cognitive disorders. Although the influence of lacking those data is not negligible, we believe that increasing MRC sum-score and decreasing the length of ICU stay are important factors affecting gait independence at hospital discharge. Second, the frequency and intensity of rehabilitation therapies provided after ICU discharge were not investigated. Finally, the first out-of-bed mobilization was performed on the sixth ICU day in our study, which is 1 day longer than the ventilation day, likely because out-of-bed mobilization was started after extubation in most patients. Lacking a shared protocol for weaning from mechanical ventilation caused delays that may contribute to decreasing MRC sum-score.

Conclusions

We analyzed factors contributing to gait independence at hospital discharge in mechanically ventilated patients in the eight ICUs sharing a uniform mobilization protocol. We found muscle weakness (ICU-AW) at ICU discharge, age, and incidence of delirium as significant determinants. Further study is warranted to clarify whether reducing ICU-AW and incidence of delirium improves gait independence.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BI:

-

Barthel Index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BPS:

-

Behavioral pain scale

- HOB:

-

Head of bed

- IMS:

-

ICU-mobility scale

- MHAQ:

-

Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- ROM:

-

Range of motion

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

References

Brahmbhatt N, Murugan R, Milbrandt EB. Early mobilization improves functional outcomes in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2010;14:321.

Dowdy DW, Eid MP, Dennison CR, Mendez-Tellez PA, Herridge MS, Guallar E, et al. Quality of life after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1115–24.

Bailey P, Thomsen GE, Spuhler VJ, Blair R, Jewkes J, Bezdjian L, et al. Early activity is feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:139–45.

Adler J, Malone D. Early mobilization in the intensive care unit: a systematic review. Cardiopulm Phys Ther J. 2012;23:5–13.

Burtin C, Clerckx B, Robbeets C, Ferdinande P, Langer D, Troosters T, et al. Early exercise in critically ill patients enhances short-term functional recovery. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2499–505.

Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM, Matte-Martyn A, Diaz-Granados N, Al-Saidi F, et al. One-year outcomes in survious of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683–93.

Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–304.

Pisani MA, Kong SY, Kasl SV, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH, et al. Days of delirium are associated with 1-year mortality in an older intensive care unit population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:1092–7.

Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1874–82.

Girard TD, Alhazzani W, Kress JP, Ouellette DR, Schmidt GA, Truwit JD, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/American College of Chest Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline: liberation from mechanical ventilation in critically ill adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:120–33.

Hanekom SD, Louw Q, Coetzee A. The way in which a physiotherapy service is structured can improve patient outcome from a surgical intensive care: a controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. 2012;11:R230.

Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, et al. International Early SOMS-guided Mobilization Research Initiative. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1377–88.

Verceles AC, Wells CL, Sorkin JD, Terrin ML, Beans J, Jenkins T, et al. A multimodal rehabilitation program for patients with ICU acquired weakness improves ventilator weaning and discharge home. J Crit Care. 2018;47:204–10.

Hodgson CL, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Berney S, Buhr H, Denehy L, et al. Trial of early activity and mobilization study investigators. A binational multicenter pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial of early goal-directed mobilization in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1145–52.

Denehy L, Skinner EH, Edbrooke L, Haines K, Warrillow S, Hawthorne G, et al. Exercise rehabilitation for patients with critical illness: a randomized controlled trial with 12 months of follow-up. Crit Care. 2013;17:R156.

Chen S, Su CL, Wu YT, Wang LY, Wu CP, Wu HD, et al. Physical training is beneficial to functional status and survival in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. J Formos Med Assoc. 2011;110:572–9.

Chiang LL, Wang LY, Wu CP, Wu HD, Wu YT. Effects of physical training on functional status in patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Phys Ther. 2006;86:1271–81.

Katz PP. Measures of Adult General Functional Status: The Barthel Index, Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), MACTAR Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire, and Modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ). Arthritis Care Res. 2003;49:15–27.

Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, Taylor K, Harry B, Passmore L, Anderson L, Baker S, Sanchez M, Penley L, Howard A, Dixon L, Leach S, Small R, Hite RD, Haponik E. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2238–43.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE. APACHEII: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818–29.

Vincent JL, de Mendonga A, Cantraine F, Moreno R, Takala J, Suter PM, et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 1998;26:1793–800.

Hodgson C, Needham D, Haines K, Bailey M, Ward A, Harrold M, et al. Feasibility and inter-rater reliability of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung. 2014;43:19–24.

Guarneri B, Bertolini G, Latronico N. Long-term outcome in patients with critical illness myopathy or neuropathy: the Italian multicentre CRIMYNE study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:838–41.

Patel BK, Pohlman AS, Hall JB, Kress JP. Impact of early mobilization on glycemic control and ICU-acquired weakness in critically ill patients who are mechanically ventilated. Chest. 2014;146:583–9.

Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, Brophy GM, O'Neal PV, Keane KA, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1338–44.

Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Truman B, Dittus R, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: validation of the Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1370–9.

Bergeron N, Dubois MJ, Dumont M, Dial S, Strobik Y. Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist: evaluation of a new screening tool. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:859–64.

Ranhoff AH, Laake K. The Barthel ADL Index: scoring by physician from patient interview is not reliable. Age and Aging. 1993;22:171–4.

Collin C, Wade DT, Davies S, Home V. The Barthel ADL Index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Studies. 1988;10:61–3.

Watanabe S, Iida Y, Ito T, Mizutani M, Morita Y, Suzuki S, et al. effect of early rehabilitation activity time on critically ill patients with intensive care unit-acquired weakness: a Japanese retrospective multicenter study. Prog Rehabil Med. 2018;3:1–9.

Secombe PJ, Stewart PC, Brown A. Functional outcomes in high risk ICU patients in Central Australia: a prospective case series. Rural Remote Health. 2013;13:2128–38.

Novak P, Vidmar G, Kuret Z, Bizovičar N. Rehabilitation of critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy patients: an observational study. Int J Rehabil Res. 2011;34:336–42.

Hermans G, Berghe GV. Clinical review: intensive care unit acquired weakness. Crit care. 2015;19:274–82.

TEAM Study Investigators, Hodgson C, Bellomo R, Berney S, Bailey M, Buhr H, et al. Early mobilization and recovery in mechanically ventilated patients in the ICU: a bi-national, multi-centre, prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2015;26(19):81.

Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, Annemans L, Decruyenaere JM. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:2386–400.

Alison JA, Kenny P, King MT, McKinjey S, Aitken LM, Leslie GD, et al. Repeatability of the six-minute walk test and relation to physical function in survivors of a critical illness. Phys Ther. 2012;92:1556–63.

Kalabalik J, Brunetti L, El-Srougy R. Intensive care unit delirium: a review of the literature. J Pharm Pract. 2014;27:195–207.

Kress JP, Hall JB. ICU-acquired weakness and recovery from critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1625–35.

Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Rochwerg B, Nunnally ME, Needham DM, Gelinas C, et al. Methodologic innovation in creating clinical practice guidelines: insights from the 2018 society of critical care medicine pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption guideline effort. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:1457–63.

de Jonghe B, Lacherade JC, Sharshar T, Outin H. Intensive care unit-acquired weakness risk factors and prevention. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:309–15.

Yosef-Brauner O, Adi N, Ben Shahar T, Yehezkel E, Carmeli E. Effect of physical on muscle strength, respiratory muscle and functional parameters in patients with intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Clin Respir. 2015;9:1–6.

Stevens RD, Dowdy DW, Michaels RK, Mendez-Tellez PA, Pronovost PJ, Needham DM. Neuromuscular dysfunction acquired in critical illness: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1876–91.

van den Boogaard M, Slooter AJC, Brüggemann RJM, Schoonhoven L, Beishuizen A, Vermeijden JW, et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;20:680–90.

Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gélinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of pain, agitation/sedation, delirium, immobility, and sleep disruption in adult patients in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:825–73.

Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC, Thompson JC, Hauser J, Flores L, et al. Standardized rehabilitation and hospital length of stay among patients with acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2694–702.

Kelmenson DA, Neumeier A, Badlam JB, Eickelberg O. Recovery from critical illness: physical rehabilitation in the intensive care unit, timing of persistent critical illness, and caregiver outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1068–70.

Routsi C, Gerovasili V, Vasileiadis I, Karatzanos E, Pitsolis T, Tripodaki E, et al. Electrical muscle stimulation prevents critical illness polyneuromyopathy: a randomized parallel intervention trial. Crit Care. 2010;14:R74.

Wolfe KS, Patel BK, MacKenzie EL, Giovanni SP, Pohlman AS, Churpek MM, et al. Impact of vasoactive medications on ICU-acquired weakness in mechanically ventilated patients. CHEST. 2018;S0012-3692(18):31110–3.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the study coordinators Dr Tetsuo Ikai, PT Tatsuya Horibe, PT Gen Kudo, Ns Masako Shimada, Dr Satoshi Endo, PT Takahumi Tani, Dr Kazuhiro Sato, PT Terasawa Tomoaki, Dr Liu Keibun, Dr Hiroaki Otake, Ns Emi Abe, PT Jin Osaki, Ns Yayoi Honjo, Ns Yasuko Muranaka, Dr Hiroaki Harada, PT Tomoya Nanba, Dr Masahiro Tamashiro, PT Hiroshi Takahashi, Ns Kazuya Oshiro, PT Daisetsu Yasumura, Dr Yuji Miyata, and Ns Masaru Moromisato. The authors would also like to thank the entire ICU staff at Nagoya Medical Center Hospital.

The authors thank Yoshifumi Kotake, MD, PhD (Department of Anesthesiology, Toho University Ohashi Medical Center), for providing assistance in reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SW, ST, HK, and TK participated in the study design. All authors participated in the data interpretation. SW, ST, MY, AR, SS, OK, IK, and MO participated in the patient care. SW and ST wrote the manuscript. YM, HK, RK, and TK assisted in critically revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research was approved by the ethics committee of each participating hospital and the ethics committee of the Nagoya Medical Center Hospital (Institutional Review Board approval number 2018-19).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Watanabe, S., Kotani, T., Taito, S. et al. Determinants of gait independence after mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: a Japanese multicenter retrospective exploratory cohort study. j intensive care 7, 53 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-019-0404-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-019-0404-2