Abstract

Canada has been home to comparatively extreme developments in prescription opioid (PO) availability and related harms (e.g. morbidity, mortality) post-2000. Following persistent pan-Canadian increases in PO use, select control measures were implemented and PO dispensing levels—while only inconsistently by province—inverted, and began to plateau or decrease post-2012. We examined annual PO dispensing levels in Canada up until 2018, based on representative prescription sample data from community-based retail pharmacies. Annual prescription-based dispensing data were converted into defined daily doses/1000 population/day by province, and mainly categorized into ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ opioids. All provinces indicated decreasing trends in strong PO levels in most recent years, yet with inter-provincial differences of up to one magnitude in 2018; in about half the provinces, dispensing fell to below-2005 levels. British Columbia had the largest decline in strong PO dispensing from its peak rate (− 48.5%) in 2011. Weak opioid dispensing trends remained more inconsistent and bifurcated across Canada. The distinct effects of individual—including many provincially initiated and governed—PO control measures urgently need to be evaluated. In the meantime, recent reductions in general PO availability across Canada appear to have contributed to shortages in opioid supply for existent, sizable (including non-medical) user populations and may have contributed to recent marked increases in illicit opioid use and harms (including rising deaths).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In North America, the epidemiological picture of high availability and use of prescription opioids (POs), and related public health consequences, are well-documented [1,2,3,4]. Post-2000, PO dispensing began to rise rapidly, resulting in the USA and Canada becoming the world's two countries with the highest PO use rates [5]. In parallel, key PO-related adverse consequences—including increases in non-medical use, morbidity (e.g. hospitalizations) and mortality (e.g. fatal poisonings)—unfolded, leading to a PO-related ‘public health crisis’ including unprecedented reductions in life expectancy [1, 3, 6]. Most of the above population-level morbidity and mortality outcomes have been shown to be strongly correlated with PO dispensing volumes [7,8,9].

North American governments and regulators began to more actively implement measures to address increasing PO-related harms post-2010 [10,11,12,13]. In Canada, this has included a variety of interventions—some fragmented given that key aspects of health policy or regulations have provincial (vs. national) oversight. Measures have included the delisting of slow-release oxycodone (‘Oxycontin’) from provincial formularies (in 2012), newly introduced and/or strengthened (provincial) prescription monitoring programmes combined with enhanced prescriber education as well as select disciplinary action against over-prescribers and introduction of restrictive opioid prescribing guidelines (in 2016/2017) [10, 14, 15]. In addition there has been growing public discussion and awareness on the consequences of opioid use over this period [16, 17].

While PO dispensing peaked in the US in about 2010 and subsequently declined by about 25% in response to control measures implemented, it remains globally unsurpassed for its opioid consumption levels [18,19,20]. In Canada, similar developments have lagged and have been less consistent, with select decreases in PO dispensing identified for half of the provinces post-2012 [21, 22]. Throughout this period, PO dispensing levels across Canadian provinces have been quite diverse, including up to threefold variations in prescribing volumes [21, 23]. Despite these overall reductions in dispensing, increases in key opioid-related harms (e.g. mortality, morbidity) have occurred across North America in recent years, increasingly driven by expanding involvement of illicit, highly toxic opioid products in the past five years [24,25,26,27].

In the following and extending previous work, we briefly examine and update on trends and patterns in PO dispensing in Canada for the period up to 2018, with primary focus on recent developments as well as population health implications.

Methods

Present analyses are based on annual PO retail dispensing data across Canada (specifically, the ten Canadian provinces) from 2005 to 2018. Raw aggregated update data were obtained from the IQVIA’s CompuScript database, which monitors prescription-based retail transactions for medications, and had been used for previous related analyses [28,29,30,31]. Totals for the number of PO prescriptions and number of units dispensed for each opioid product were provided by IQVIA aggregated by region (provinces), opioid molecule (codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, methadone, morphine, oxycodone or tramadol), product names, form (solid, liquid, etc.) and strength. Methadone formulations were provided but excluded from the analyses since they are primarily used for addiction treatment, and dispensing modes greatly vary [32]. As tramadol has only been available in Canada since 2006 data were not available for the full study period. However, their inclusion (among ‘weak opioids’) showed to not alter observed overall patterns within provinces [33].

The individual provincial summary of total dispensing data were converted to annual defined daily doses per 1000 population per day (DDD/1000/day) values. DDD estimates were obtained from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification and DDD measurement methodology, population statistics calculated from the Statistics Canada’s CANSIM table 051-0005 [34,35,36]. Based on the WHO’s pain ladder, tramadol and codeine formulation products were defined as ‘weak’ opioids, all other formulations were combined into ‘strong’ opioids for descriptive analysis [37].

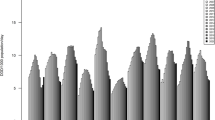

Descriptive analyses for the different PO categories included low- and high-ranking values in dispensing and change rates, by province and over-time [Fig. 1]. No ethical approval was required for the present study based on the nature of the non-personalized, population-aggregate dispensing data used for analyses.

Total prescription opioid dispensing (without methadone) in annual DDD/1000 population/day in Canada, by province, 2005–2018. Full names of provinces (acronyms used in text and figure): BC, British Columbia; AB, Alberta; SK, Saskatchewan; MN, Manitoba; ON, Ontario; NB, New Brunswick; NS, Nova Scotia; PE, Prince Edward Island; NL, Newfoundland and Labrador; CA, Canada (total)

Results

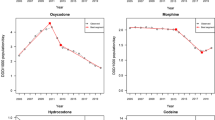

In 2018, British Columbia (BC) (5.1 DDD/1000 pop/day) featured the lowest strong PO dispensing rate and Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) had the highest (10.1 DDD/1000 pop/day), approximately double the rate. Most provinces reported their peak rates for strong PO dispensing in 2011 but no later than 2016. All provinces indicated multi-year decreasing trends in strong PO dispensing in recent years and lower dispensing compared to previous peak rates; four out of the ten provinces indicated strong PO dispensing rates in 2018 that were below 2005-levels. Compared with respective peak years, BC had the greatest (− 49.5% from 2011), Quebec the smallest (− 13.8% from 2016) relative reduction in strong PO dispensing within the study period.

Correspondingly, BC (2.6 DDD/1000 pop/day) featured the lowest weak PO dispensing rate and Alberta (AB) had the highest (17.1 DDD/1000 pop/day) in 2018, equating to more than a sixfold difference. All provinces had lower dispensing rates for weak POs compared to previous peak rates observed during the study period, and all but one of the provinces (Saskatchewan [SK]) had weak PO dispensing rates that were below 2005 levels. Compared with respective peak years, ON had the greatest (− 43.1% from 2005) and NL the smallest relative reduction (− 11.8% from 2014) in weak PO dispensing within the study period.

Discussion

The PO dispensing data presented is drawn from a stratified, representative sample of about 6,000 (approximately two thirds of the total) retail pharmacies across Canada, including a continuously refreshed sub-sample providing the pharmaceutical dispensing data comprising the large majority of prescriptions at the national level [28, 38]. The Compuscript panel projects the sample-based prescription data to the universe of pharmacies by province, with a sampling error that is estimated to be low (5–10%) and data representativeness considered good. About 80% of the total of POs in Canada are dispensed through retail pharmacies (with other routes, including hospital-based dispensing, not captured) [29]. Over this time period, Canadian pharmacies could sell select codeine (e.g., cough or mild pain/fever) medication) 'over-the-counter' without a prescription; however, these sales are not included in the present data [39, 40]. Overall, this is probably the best available data snapshot on country-wide PO consumption based on DDD values, interpreted as a drug’s average maintenance dose per day for its main indication for an average adult. DDDs are a measurement unit with limits in accuracy, yet are seen as superior to indicators like crude prescription numbers, especially for comparative analyses [41,42,43].

Our data—building on previous pharmaco-epidemiologic analyses—showed that population-level PO dispensing has undergone distinctly oscillating waves and changes in Canada during the period 2005–2018 [22, 23, 29]. While there were stark pan-Canadian increases especially in strong PO dispensing up until 2011, making Canada a global co-lead in opioid usage, all provinces have featured subsequent declines in dispensing more recently [5, 20]. These recent declines in strong PO dispensing, however, vary considerably in terms of timing and relative reductions [21, 22]. Nevertheless, it is a fair overall summary that following a general ‘wave’ of strong PO dispensing increases until halfway through the study period, and an inversion occurred involving a second, ‘downward’ wave in strong PO dispensing thereafter in Canada.

Notably, by 2018, some provinces have reduced their strong PO dispensing to below 2005 levels—a time when more generous opioid dispensing was actively promoted towards improved chronic pain care outcomes [44,45,46]. While the prevalence of chronic pain in the Canadian population does not appear to have changed, preeminent pain treatment guidelines and other prescription-related advise have undergone a virtual ‘180 degree’ turn, basically from recommending ‘generous opioids provision’ to ‘sparing or “last resort” resort use only’. One would expect tangible empirical impact on pain care outcomes from a period in which opioid usage inverted by such magnitudes in a national population over the period of less than two decades [15, 47,48,49]. Moreover, dispensing trends for weak opioids showed less consistent patterns in an environment increasingly cautious about medical codeine usage [50]: about half the provinces featured substantial overall declines, others remained generally stable in weak PO dispensing, while at differential quantity levels.

It is reasonable to assume that the pronounced recent decreases especially in strong PO dispensing across Canada are an overall consequence of the various opioid control measures—including opioid product delisting, prescription monitoring and revised prescription guidelines—implemented in Canada over the past decade [49, 51,52,53]. Unfortunately, only most limited evaluations exist as to the impact of these individual interventions on variations in PO availability—whether on provincial or national levels—even though this information would be crucially important for evidence-based interventions and policy development towards optimized opioid control and related benefits and/or harms [2, 10, 54]. Such analyses urgently need to be conducted with appropriate, rigorous approaches, for example time-series and other analysis methods [52, 55]. Overall and despite recent declines combined with some inter-provincial alignment, the total of strong PO dispensing patterns remains rather heterogeneous across Canadian provinces, as further exemplified by variations in the types of opioid formulations used [21].

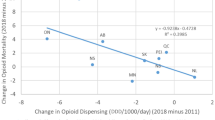

One would expect that the recent declines in population-level opioid dispensing in Canada co-occurred with parallel benefits in opioid-related public health outcomes. Unfortunately, this appears not to be the case, or reductions from excessive prescribing levels occurred too late, evidence for improvements in pain care outcomes is lacking, and opioid-related mortality and morbidity indicator outcomes have substantially risen further in recent years (e.g. 2017/18) [56,57,58]. Contributing factors to this dire situation are multi-layered and include the increasing availability and non-medical use—despite substantially expanded public health and treatment interventions—of illicit, highly potent and toxic opioid products (e.g. fentanyl or analogues) by many at-risk users in locations across Canada [25, 26, 59]. While these developments in rising illicit opioid use and harms appear to be extrinsically driven, the impact of a suddenly and rapidly shrinking (direct or indirect/diverted) medical opioid supply for large populations habituated into (medical or non-medical) opioid use in Canada need to be better analyzed and understood [60, 61]. Further epidemiological analyses and improved intervention and policy development for this opioid-related public health crisis are urgently required.

Conclusion

Following persistent increases that gave Canada one of the highest opioid use rates in the world, an assortment of various policy interventions implemented post-2012 to curb general opioid availability and adverse consequences in the population were introduced, and prescription opioid dispensing showed variably decreasing trends in each of ten provinces. Both the magnitude of the decreases and current opioid dispensing levels continue to be rather heterogeneous across the provinces and so raise questions about differential medical use and needs standards, as well as the effectiveness of policy measures for opioids. From a public health perspective, the substantive decreases in medical opioid availability appears to have led to unintended consequences of supply shortages for non-medical opioid use resulting in extensive adverse outcomes (e.g. overdose fatalities) related to increases in illegal opioid (e.g. fentanyl and analogues) availability and use.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets (Statistics Canada) analysed during the current study are publicly available from Statistics Canada [https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901]; the opioid dispensing data are not publicly available since underlying data were commercially obtained and used under licence. The commercial data provider had no involvement in or influence on analyses, interpretation or publication of the data.

Abbreviations

- PO:

-

Prescription opioid(s)

References

Murphy Y, Goldner E, Fischer B. Prescription opioid use, harms and interventions in Canada: a review update of new developments and findings since 2010. Pain Physician. 2015;18:E605–E14.

Belzak L, Halverson J. Evidence synthesis-the opioid crisis in Canada: a national perspective. Health promotion and chronic disease prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice. 2018;38(6):224.

Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, Kreiner P, Eadie JL, Clark TW, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559–74.

Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2017. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2019;67(5152):1419.

International Narcotics Control Board. Availability of internationally controlled drugs: ensuring adequate access for medical and scientific purposes. New York: International Narcotics Control Board (INCB), 2016 April 29, 2019.

Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(49):15078–83.

Sauber-Schatz EK, Mack KA, Kiekman ST, Paulozzi L. Associations between pain clinic density and distributions of opioid pain relievers, drug-related deaths, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and neonatal abstinence syndrome in Florida. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):161–6.

Fischer B, Jones W, Urbanoski K, Skinner R, Rehm J. Correlations between prescription opioid analgesic dispensing levels and related mortality and morbidity in Ontario, Canada, 2005-2011. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2014;33(1):19–26.

Gladstone EJ, Smolina K, Weymann KR, Morgan SG. Geographic variations in prescription opioid dispensations and deaths among women and men in British Columbia, Canada. Med Care. 2015;53(11):954–9.

Fischer B, Rehm J, Tyndall M. Effective Canadian policy to reduce harms from prescription opioids: learning from past failures. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):1240–4.

Rutkow L, Chang HY, Daubresse M, Webster DW, Stuart EA, Alexander GC. Effect of Florida's prescription drug monitoring program and pill mill laws on opioid prescribing and use. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;174(10):1642–9.

Volkow N, McLellan TA. Curtailing diversion and abuse of opioid analgesics without jeopardizing pain treatment. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1346–7.

Meyer R, Patel MA, Rattana SK, Quock TP, Mody SH. Prescription opioid abuse: a literature review of the clinical and econimic burden in the United States. Population Health Management. 2014;17(6):372–87.

Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624–45.

Busse JW, Craigie S, Juurlink DN, Buckley DN, Wang L, Couban RJ, et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Can Med Assoc J. 2017;189(18):E659–E66.

Health Canada. Federal action on opioids Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2019. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/problematic-prescription-drug-use/opioids/federal-actions.html. Retrieved: April 10, 2019.

The Globe and Mail. More than 10,000 Canadians have died from opioid-related overdoses since 2016, public health data show. Retrieved: April 10 2019.

Guy GP Jr, Zhand K, Bohm MK, Losby J, Lewis B, Young R, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2017;66(26):697.

Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, US, 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409–13.

International Narcotics Control Board. Narcotic drugs 2018. New York: International Narcotics Control Board (INCB); 2018.

Fischer B, Jones W, Vojtila L, Kurdyak P. Patterns, changes, and trends in prescription opioid dispensing in Canada, 2005-2016. Pain Physician. 2018;21(3):219–28.

Fischer B, Jones W, Rehm J. Trends and changes in prescription opioid analgesic dispensing in Canada 2005-2012: an update with a focus on recent interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):90.

Canadian Institutes for Health Information. Pan-Canadian trends in the prescribing of opioids, 2012 to 2016. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), 2017.

Frank RG, Pollack HA. Addressing the fentanyl threat to public health. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):605–7.

Fischer B, Vojtila L, Rehm J. The ‘fentanyl epidemic’in Canada–some cautionary observations focusing on opioid-related mortality. Prev Med. 2018;107:109–13.

Gomes T, Khuu W, Martins D, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, et al. Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ. 2018;362:k3207.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose Death Rates (Revised 2019) North Bethesda, MD, USA: National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA); 2019. Available from: https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

IMS Brogan (IMSB). IMSB Canadian compuscript audit. Available from: http://www.imsbrogancapabilities.com/.

Fischer B, Jones W, Krahn M, Rehm J. Differences and over-time changes in levels of prescription opioid analgesic dispensing from retail pharmacies in Canada, 2005-2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(12):1269–77.

IQVIA. Retail Prescriptions Dispensed in Canada, 2013-2017. Pharmaceutical trrends 2018. IQVIA; 2018. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/canada-location-site/retailprescriptionscanada_en_17.pdf?la=en&hash=F4B8ABE5F640247F99D9CF104E79BC3A18DD4158.

CIHI. Pan-Canadian trends in the prescribing of opioids and benzodiazepines, 2012 to 2017, vol. 2018. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI).

Fischer B, Kurdyak P, Goldner E, Tyndall M, Rehm J. Treatment of prescription opioid disorder in Canda: looking at the 'other epidemic'? Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy. 2016;11(1):12.

Fischer B, Kurdyak P, Jones W. Tramadol dispensing patterns and trends in Canada, 2007-2016. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28(3):396–400.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Methodology: definition and general considerations. World Health Organization (WHO). Available from: http://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/.

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC/DDD index. World Health Organization (WHO). Available from: http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Retrieved: April 9, 2019.

Statistics Canada. Population estimates, quarterly, Table: 17-10-0009-01 [cited 2020 August 19] Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2020. Available: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1710000901. Retrieved: August 19, 2020.

World Health Organization. WHO's Pain Ladder. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/. Retrieved: April 10, 2020.

IMSB. Canadian Compuscript audit [computer program]. IMS Brogan: Montreal; 2013.

Drug & Alcohol Testing Association of Canada. Cough syrups with codeine to become controlled medications 2019. Available: https://datac.ca/cough-syrups-with-codeine-to-become-controlled-medications/. Retrieved: April 10, 2020.

MacKinnon J. Tighter regulations needed for over-the-counter codeine in Canada. Canadian Pharmacists Journal/Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada. 2016;149(6):322–4.

Nielsen S, Gisev N, Bruno R, Hall W, Cohen M, Larance B, et al. Defined daily doses (DDD) do not accurately reflect opioid doses used in contemporary chronic pain treatment. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(5):587–91.

McDonald DC, Carlson K, Izreal D. Geographic variation in opioid prescribing in the US. J Pain. 2012;13(10):988–96.

Ontario Drug Policy Research Network. Behind the prescriptions: a snapshop of opioid use across all Ontarians. Toronto, ON: Ontario Drug Policy Research Network (ODPRN); 2017 April 29 2019.

Jovey RD, Ennis J, Gardner-Nix J, Goldman B, Hays H, Lynch M, et al. Use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic noncancer pain - a consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society, 2002. Pain Research and Management. 2003;8:3A–14A.

Moulin DE, Clark AJ, Speechley M, Morley-Forster PK. Chronic pain in Canada-prevalence, treatment, impact and the role of opioid analgesia. Pain Research and Management. 2002;7(4):179–84.

Mularksi RA, White-Chu F, Overbay D, Miller L, Asch SM, Ganzini L. Measuring pain as the 5th vital sign does not improve quality of pain management. J Gen Internal Medicine. 2006;21(6):607–12.

Schopflocher D, Taenzer P, Jovey R. The prevalence of chronic pain in Canada. Pain Research and Management. 2011;16(6):445–50.

Boulanger A, Clark AJ, Squire P, Cui E, Horbay GL. Chronic pain in Canada: have we improved our management of chronic noncancer pain? Pain Research and Management. 2007;12(1):39–47.

Busse J, Jurrlink D, Guyatt GH. Addressing the limitations of the CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):1210–1.

MacDonald N, MacLeod SM. Has the time come to phase out codeine? CMAJ. 2010;182(17):1825.

Furlan AD, MacDougall P, Pellerin D, Shaw K, Spitzig D, Wilson G, et al. Overview of four prescription monitoring/review programs in Canada. Pain Research Management. 2014;19(2):102–6.

Gomes T, Juurlink D, Yao Z, Camacho X, Paterson JM, Singh S, et al. Impact of legislation and a prescription monitoring program on the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions for monitored drugs in Ontario: a time series analysis. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E256.

Fischer B, Vojtila L, Kurdyak P. ‘Delisting’OxyContin® to reduce prescription opioid-related harms in Ontario (Canada)—gauging effects 5 years later. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(9):1040–3.

Ansari B, Tote KM, Rosenberg ES, Martin EG. A rapid review of the impact of systems-level policies and interventions on population-level outcomes related to the opioid epidemic, United States and Canada, 2014-2018. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(1_suppl):100S–27S.

Clarke H, Bao J, Weinrib A, Dubin RE, Kahan M. Canada's hidden opioid crisis: the health care system's inability to manage high-dose opioid patients: fallout from the 2017 Canadian opioid guidelines. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65(9):612–4.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Opioid-related harms in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI); 2018.

Public Health Agency of Canada. National report: apparent opioid-related deaths in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2019.

Gomes T, Greaves S, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Measuring the burden of opioid-related mortality in Ontario, Canada. J Addict Med. 2018;12(5):418.

Baldwin N, Gray R, Goel A, Wood E, Buxton JA, Rieb LM. Fentanyl and heroin contained in seized illicit drugs and overdose-related deaths in British Columbia, Canada: an observational analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;185:322–7.

Fischer B, Pang M, Tyndall M. The opioid death crisis in Canada: crucial lessons for public health. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(2):81–2.

Unick GJ, Rosenblum D, Mars S, Ciccarone D. Intertwined epidemics: national demographic trends in hospitalizations for heroin-and opioid-related overdoses, 1993-2009. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e54496..

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present work was partly supported by funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), specifically grant #SAF-94814. Dr. Fischer acknowledges support from the endowed Hugh Green Foundation Chair in Addiction Research, Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland. The present study was partly conducted with opioid dispensing data commercially obtained from IQVIA solutions. None of the authors is affiliated with the company, and the company had no involvement in the study design, analyses or manuscript development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BF conceptualized the paper and prepared the initial draft. WJ conducted the statistical analyses. WJ, LV and PK reviewed and provided intellectual contributions to data and interpretation materials. BF and WJ, together with other co-authors, led iterative revisions of drafts of the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, W., Vojtila, L., Kurdyak, P. et al. Prescription opioid dispensing in Canada: an update on recent developments to 2018. J of Pharm Policy and Pract 13, 68 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-020-00271-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-020-00271-x