Abstract

Background

Different methods in pharmacoepidemiology can be used to study hypnotic use in children. But neither questionnaire-based data nor prescription records can be considered a “gold standard”. This study aimed to investigate the agreement between mother-reported questionnaire-based data and prescription record data for hypnotic drugs in children aged 0–18 months. The agreement was compared to the agreement for a group of antiepileptic drugs.

Methods

Prescription record data were collected from the Norwegian prescription database for 47,413 children also surveyed in the Norwegian mother and child cohort between 2005 and 2009. Agreement between in the two data sources was calculated using Cohens Kappa. Multinomial logistic regression was used to calculate the effect of sociodemographic variables on discrepancies in data sources.

Results

The agreement between mother-reported and dispensed hypnotics was less than 50% for all hypnotics. Sensitivity of reporting increased with number of filled prescriptions. The agreement of antiepileptic drugs was 92.9% in the same population. Of several sociodemographic factors only paternal educational level and maternal work situation was significantly related to agreement between prescription record and survey data.

Conclusion

There was a moderate agreement between reported use and dispensed hypnotic drugs for infants and toddlers. Results indicate that sociodemographic factors play only a minor role in explaining discrepancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prescribing sleep-inducing medication for otherwise healthy infants and toddlers is a controversial subject. Different countries have different therapeutic traditions, but pharmacological treatment of sleep problems in the youngest children is frequent in many countries [1,2,3,4]. For infants and toddlers antihistamines, α2-agonists or chloral hydrate are most often the drugs of choice, while melatonin, benzodiazepines and the benzodiazepine like z-hypnotics (i.e. zolpidem, zopiclone) are mainly prescribed for older children and teen-agers [3, 4]. In Norway, the antihistamine alimemazine (an aliphatic phenothiazine) is the most used sleep inducing drug in infants and toddlers, despite not being approved for the age group less than 2 years of age [1, 3, 5,6,7,8,9].

There is a lack of evidence of effect and safety for sleep inducing drugs to small children. This is especially true for the older drugs introduced in a time where drugs testing was less regulated. To compensate for this, observational studies of real life use in children can be useful. There are many types of data sources for such studies and all will have their strengths and limitations, but few studies have estimated the quality of different data sources on the use of prescription drugs in young children. Two such data sources may be survey data and prescription data. However both sources have their limitations and none of them can be considered the “gold standard” [10]. One prior study, comparing the Norwegian Prescription Database (NorPD) with maternal report of prescribed anti-asthma drugs for children aged 7 years in the Norwegian Mother and child cohort study (MoBa) showed high agreement with maternal report [11]. However, little is known about other drugs.

The aim of this study was to investigate the agreement between maternal-report on sleep inducing drug use by 0–18 month’s old children in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort with information on dispensed hypnotic drugs from pharmacies in the Norwegian Prescription Database. The results were compared with the agreement for antiepileptic drugs that should be taken more regularly for a chronic somatic disease, thus theoretically representing a drug with an expected higher agreement between the two data sources. Since alimemazine traditionally is used in Norway as a hypnotic drug to young children, we finally estimated the extent to which sociodemographic background variables and the number of prescriptions of alimemazine could account for possible discrepancies.

Methods

MoBa

The Norwegian Mother and Child cohort study (MoBa) is a prospective population-based pregnancy cohort study conducted by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and aims to study causes of disease [12, 13]. Women were invited to join after attending routine ultrasound appointment in pregnancy week 18. From one participating hospital in one region in 1999 the study gradually included more hospitals. In the period 2005–2008 almost all Norwegian women were invited to participate. Overall in the period 1999 to 2008 approximately 41% of the invited consented to participation. The last birth into the cohort was in June 2009. The MoBa study collected questionnaires at specific time points; our study uses questionnaires from baseline and at child’s age 6 and 18 months [14]. The personal identification numbers [15] assigned to all individual in Norway allow for linking of MoBa data with other registries and studies. In this study, MoBa data was linked to data from the Norwegian Prescription Database.

Norwegian prescription record (NorPD)

NorPD holds a complete record of all dispensed prescription drugs since 2004 [16]. Pharmacies are obliged to register prescriptions electronically and submit information every month. NorPD includes both prescriptions made to individuals and institutions, but prescriptions in institutions are not registered at a person level [17]. For each prescription drug specific information, patient data and prescriber information are registered. In the present study we only studied prescriptions made to children in the MoBa study. We used information on patient ID, drug name, date of dispensing, and reimbursement code.

Sample

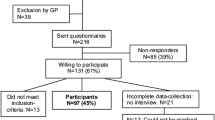

To ensure that information was available from both data sources, we only included children in MoBa when the 6 month questionnaire was filled after 1. January 2005. Both the 6 months and the 18 months questionnaire had to be filled in for the child to be included in our study. The study population thus consisted of 47,310 children (see Fig. 1).

From baseline questionnaires we used the following information: parents’ age, family income, parents’ education, if the pregnancy was planned or not, maternal marital status, maternal parity and maternal employment status. From the 6 and 18 months questionnaires we used reported drug use (Additional file 1). Trained personnel interpreted and converted drug names from the questionnaires to ATC codes when entering data.

Drugs included in the study

For the present study information on all anxiolytics, hypnotics and sedatives, dexchlorpheniramine, alimemazine and promethazine was used (Table 1). As comparison we also included a group of antiepileptic drugs recommended as first choices for treatment of childhood epilepsy [18]; Carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, topiramate, and valproate.

From NorPD we included hypnotics and antiepileptics dispensed to the child from birth until the date the mother filled the 18 months questionnaire.

Analysis strategy and statistics

-

a)

Reported (yes/no) and dispensed prescriptions (yes/no) for all hypnotic drugs and the control group of antiepileptic drugs were cross-tabulated. We used Cohen’s Kappa with Fleiss’ subdivision to determine agreement between reported use and registry data (Table 1) [19].

-

b)

Prescriptions for alimemazine were subdivided into categories based on number of prescriptions (0, 1, 2 and 3 or more) and we compared this to information on reported alimemazine use from the questionnaires(yes/no). Setting prescription record data as reference standard, we measured sensitivity of reporting by number of prescriptions (Table 2).

-

c)

Mother-reported sociodemographic data was used to characterize the children with discrepancy between reported use and dispensed prescriptions of alimemazine. We compared three groups: 1) Only mother-reported alimemazine use in MoBa, 2) Only dispensed alimemazine in the NorPD prescription record and 3) Both mother-reported use and dispensed prescriptions for alimemazine. The groups were compared using the Chi-square test (Table 3). The sociodemographic variables showing significance (p < 0.1) in Table 3 were included in a multinomial logistic regression analysis. The outcome measure was the relative risk (RR) with confidence intervals, using the category both mother-reported use and dispensed prescriptions for alimemazine as reference category.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 for Windows.

Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from mothers before inclusion in MoBa. The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Protection Authority approved the linkage of NorPD and MoBa.

Results

Prevalence of hypnotic use

The prevalence of hypnotic drug use was lower in the mother-reported MoBa study than in the prescription database NorPD for all groups of medications except promethazine (Table 2). Alimemazine and dexchlorpheniramine were the two substances most frequently reported used and dispensed. Alimemazine was reported used by 367 (0.8%) children, but was dispensed to 746 (1.6%) children under the age of 18 months. Dexchlorpheniramine was reported used by 1131 (2.4%) children in MoBa, but 2103 (4.4%) had filled a prescription according to NorPD.

Agreement between mother-reported use (MoBa) and dispensed (NorPD) hypnotic drugs.

The agreement between the two data sources was lower than 50% for all the hypnotic drugs. It was best for alimemazine (46.3%) and poorest for anxiolytics (19.1%). The agreement was, however, excellent for the group of antiepileptic’s recommended for childhood epilepsy (92.9%) (Table 2).

The sensitivity of the mother-reported alimemazine use increased by numbers of prescriptions filled. Sensitivity was 30.3% when the children had received only one prescription, increasing to 48.1% for children receiving two prescriptions and to 66.7% for those receiving 3 prescriptions or more (Table 3).

Sociodemographic background variables

The differences of sociodemographic characteristics between mother-reported use and prescription record data of alimemazine use are shown in Table 4. The adjusted multinomial logistic regression analysis showed that when fathers had higher education the risk of children’s alimemazine use being only mother-reported was 2.3 times higher (95% Confidence interval [95% CI] 1.3–3.9) than having consistent data in both mother-reported MoBa and prescription record NorPD. Mothers being unemployed increased the risk of children being in the prescription record group only, 1.9 times (95%CI 1.0–3.4) as opposed to the group with consistent data in both sources(data not shown).

Discussion

The agreement between mother-reported hypnotic drug use by their child and data on dispensed prescriptions was found to be moderate to poor for hypnotic drugs. For alimemazine, agreement increased with increasing numbers of dispensed prescriptions. With the exception of paternal education and mothers work situation, no differences in social factors between reported use and dispensed alimemazine were seen.

Mother-reported drug use was generally lower than prescriptions would imply. Some of the dispensed drugs were probably not taken as the questionnaires asked for use of medication not received prescriptions. Theoretically, using filled prescriptions as opposed to prescribed prescriptions should increase the adherence, as we at least know that the drugs were in the patient’s possession. However, when using data on dispensed medication we still do not know if the medication was actually taken or subject to so called secondary non-compliance. Many patients are not adherent to prescribed drug therapy [20]. A Canadian study of non-adherence found that sedative- hypnotics had a 35% frequency of non-adherence among the general population [21]. The lower frequency of mother-reported drug use could in this sense be closer to reality than dispensed prescriptions.

Reporting -no use of a hypnotic drug even when a prescription had been filled can also be due to lack of memory. It’s more difficult to remember drug use happening a long time ago [10, 22], drugs taken as needed [23,24,25] and drug use when asked open-ended questions [26]. Hypnotic drugs for small children is controversial and thus might be afflicted with feelings of shame and guilt by the mother, which in turn could have caused lower agreement. Others studies have shown larger discrepancies between prescribed and reported use when the drugs are afflicted with stigma [24, 27]. In MoBa the mothers were asked open questions about their child’s drug use up to a year earlier. On the other hand, the high agreement we found for chronically used antiepileptic drugs indicates that the long time periods and open-ended questions was not a problem. A study validating the same data sources in children aged 7 years but with specific asthma questions found higher agreement [11]. The agreements we found for systemic antihistamines and for antiepileptic drugs were similar to those found among pregnant women reporting on their own use of drugs in an Italian study [28].

Perhaps more surprising is the large number of mothers who reported use of alimemazine even if no prescription was filled. Possible explanations could be that the drugs had been prescribed for someone else, purchased abroad or even been given to the child while in hospital, such use would not be captured in the prescription database. Alimemazine is frequently used as sleep inducer for children in hospitals [16].

A large proportion of prescriptions to the age group 0–2 years had missing identification numbers in the years 2006–2007 due to a problem with assignment of these numbers to new-borns (personal communication Olaug Sveinsgjerd Fenne). However, the high agreement for antiepiletics might indicate that this problem was not dominant in our selection.

We did not find any substantial systematic differences of sociodemographic variables on discrepancy between mother-reported information and data on dispensed medication. Family income, marital status, parity, mothers age, if the pregnancy was planned or not and mother’s education were all similar between the groups. Non-working mothers had a higher percentage of drug only reported in the prescription record whereas families with college educated fathers had more use only reported in the cohort study. But considering that other similar variables like family income and maternal education level did not influence the outcome this might not be clinically relevant findings. Results from other studies indicate that the effect of sociodemographic variables on recall is conflicting. Some find no effect of sociodemographic variables [29, 30] whereas age and education level have been shown to affect recall, but in different directions [10, 28, 31,32,33,34].

The Norwegian Mother and Child cohort study included more than 100,000 pregnancies and continues to follow the children through life. Of the included women 87% completed the 6 months questionnaire and 77% completed the 18 months questionnaire [35]. Compared with the average pregnant woman the participants were more often living with a partner, less likely to smoke, more likely to be compliant to health advice, older and less likely to have more than two children, despite of this the bivariate associations between exposure and outcome variables for eight different conditions were not statistically different from those of the general population [12, 35]. In MoBa mothers are asked to remember drugs use up to 1 year prior. Large longitudinal studies like MoBa must make a trade-off between amount of information and the burden placed on the participants. The scope of this study was to evaluate existing sources of drug use information with the limitation they have.

This study is one of very few studies comparing mother-reported survey data with prescription data for hypnotic use among infants and toddlers. Reliable sources of information on medication use are important in clinical and epidemiological research. In the paediatric field there are still many unanswered questions about drug use and drug safety and evaluating data sources in this field is thus especially interesting. Like former studies performed on adults and adolescents this study on children shows that generally agreement between different sources of drug use is better for prescription drugs used chronic than drugs taken as needed [36, 37].

Conclusion

There was a moderate agreement between reported use and dispensed hypnotic drugs for infants and toddlers. There were, however, few differences between the two sources of data when considering sociodemographic variables. This might indicate that there are not systematic differences between the group who has been dispensed an hypnotic drug and those who report to have used it.

Abbreviations

- MoBa:

-

Norwegian mother and child cohort study

- NorPD:

-

Norwegian prescription database

References

Hartz I, Furu K, Bratlid T, Handal M, Skurtveit S. Hypnotic drug use among 0-17 year olds during 2004-2011: a nationwide prescription database study. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(8):704–11.

Stojanovski SD, Rasu RS, Balkrishnan R, Nahata MC. Trends in medication prescribing for pediatric sleep difficulties in US outpatient settings. Sleep. 2007;30(8):1013–7.

Heussler H, Chan P, Price AM, Waters K, Davey MJ, Hiscock H. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of sleep disturbance in children: an Australian paediatric research network survey. Sleep Med. 2013;14(2):189–94.

Owens JA, Rosen CL, Mindell JA. Medication use in the treatment of pediatric insomnia: results of a survey of community-based pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 1):e628–35.

Sorensen E. Sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2009;129(19):2000–3.

Holdo I, Handal M, Skurtveit S, Bramness JG. Association between prescribing hypnotics for parents and children in Norway. Arch Dis Child. 2013;98(9):732–6.

Slordal L, Bramness JG. Is alimemazine a suitable sleeping agent for children? Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2008;128(19):2194–6.

Sanz EJ. Drug prescribing for children in general practice. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87(5):489–90.

Lissauer T, Clayden G. Illustrated textbook of paediatrics, vol. 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Mosby; 2001.

West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, Strom BL, Guess HA, Hartzema A. Recall accuracy for prescription medications: self-report compared with database information. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(10):1103–12.

Furu K, Karlstad O, Skurtveit S, Haberg SE, Nafstad P, London SJ, Nystad W. High validity of mother-reported use of antiasthmatics among children: a comparison with a population-based prescription database. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(8):878–84.

Magnus P, Irgens LM, Haug K, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stoltenberg C. Cohort profile: the Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(5):1146–50.

Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, Haugan A, Alsaker E, Daltveit AK, Handal M, Haugen M, Hoiseth G, Knudsen GP, et al. Cohort profile update: the Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(2):382–8.

Questionnaires from MoBa [https://www.fhi.no/en/studies/moba/for-forskere-artikler/questionnaires-from-moba/]. Accessed 13 June 2016.

Irgens LM. The medical birth registry of Norway. Epidemiological research and surveillance throughout 30 years. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(6):435–9.

Furu K. Establishment of the nationwide Norwegian prescription database (NorPD) - new opportunities for research in pharmacoepidemiology in Norway. Nor Epidemiol. 2008;18(2):129–36.

Rønning M, Berg C, Furu K, Litleskare I, Sakshaug S, Selmer R, Skurtveit S, Strøm H. Reseptregisteret 2005-2009. Tema: Vanedannende legemidler, Folkehelseinstituttet. Statistikk 2010. ISBN: 978-82-8082-409-7, ISBN (elektronisk): 978-82-8082-408-0, ISSN: 1890-9647.

Generell veileder i pediatri [http://www.helsebiblioteket.no/retningslinjer/pediatri/forside]. Accessed 01 Aug 2015.

Fleiss JL. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 1981.

Sabaté E. Adherence to long-term therapies : evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

Bulloch AG, Patten SB. Non-adherence with psychotropic medications in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(1):47–56.

West SL, Ritchey ME, Poole C. Validity of Pharmacoepidemiologic drug and diagnosis data. In: Pharmacoepidemiology. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012. p. 757–94.

Stephansson O, Granath F, Svensson T, Haglund B, Ekbom A, Kieler H. Drug use during pregnancy in Sweden - assessed by the prescribed drug register and the medical birth register. Clin Epidemiol. 2011;3:43–50.

Nielsen MW, Sondergaard B, Kjoller M, Hansen EH. Agreement between self-reported data on medicine use and prescription records vary according to method of analysis and therapeutic group. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(9):919–24.

Monster TB, Janssen WM, de Jong PE, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Pharmacy data in epidemiological studies: an easy to obtain and reliable tool. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2002;11(5):379–84.

Mitchell AA, Cottler LB, Shapiro S. Effect of questionnaire design on recall of drug exposure in pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;123(4):670–6.

Skurtveit S, Selmer R, Tverdal A, Furu K. The validity of self-reported prescription medication use among adolescents varied by therapeutic class. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(7):714–7.

Pisa FE, Casetta A, Clagnan E, Michelesio E, Vecchi Brumatti L, Barbone F. Medication use during pregnancy, gestational age and date of delivery: agreement between maternal self-reports and health database information in a cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:310.

Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Rossignol M, Aubrun E, El Kerri N, Benichou J, Abenhaim L. Agreement between patients' self-report and physicians' prescriptions on cardiovascular drug exposure: the PGRx database experience. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(6):591–5.

Sarangarm P, Young B, Rayburn W, Jaiswal P, Dodd M, Phelan S, Bakhireva L. Agreement between self-report and prescription data in medical records for pregnant women. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94(3):153–61.

West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, Sheff KL, Strom BL, Guess HA, Hartzema AG. Demographics, health behaviors, and past drug use as predictors of recall accuracy for previous prescription medication use. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(8):975–80.

Stolley PD, Tonascia JA, Sartwell PE, Tockman MS, Tonascia S, Rutledge A, Schinnar R. Agreement rates between oral contraceptive users and prescribers in relation to drug use histories. Am J Epidemiol. 1978;107(3):226–35.

Rockenbauer M, Olsen J, Czeizel AE, Pedersen L, Sorensen HT. Recall bias in a case-control surveillance system on the use of medicine during pregnancy. Epidemiology. 2001;12(4):461–6.

Radin RG, Mitchell AA, Werler MM. Predictors of recall certainty of dates of analgesic medication use in pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(1):25–32.

Nilsen RM, Vollset SE, Gjessing HK, Skjaerven R, Melve KK, Schreuder P, Alsaker ER, Haug K, Daltveit AK, Magnus P. Self-selection and bias in a large prospective pregnancy cohort in Norway. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2009;23(6):597–608.

Skurtveit S, Selmer R, Odsbu I, Handal M. Self-reported data on medicine use in the Norwegian mother and child cohort study compared to data from the Norwegian prescription database. Nor Epidemiol. 2014;24(1–2):209–16.

Furu KSS, Rosvold EO. Drug use questions in Norwegian health surveys – response rate and agreement between specific and open-ended questions. Nor Epidemiol. 2003;13(1):147–54.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the group responsible for the project 2012/570 Sleep medication in younger children for allowing this paper to be a part of their project. Thank you to administrative staff and coworkers at both Norwegian Institute of Public Health and University of Oslo for supporting the authors, answering questions and helping with both technical and content related questions. Thank you to the Norwegian Prescription Database and the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study for providing the data for this publication. The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study are supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research, NIH/NIEHS (contract no N01-ES-75558), NIH/NINDS (grant no.1 UO1 NS 047537-01 and grant no.2 UO1 NS 047537-06A1). We are grateful to all the participating families in Norway who take part in this on-going cohort study.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Funded by internal sources from Norwegian Centre for Addiction Research only.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from The Norwegian Institute of Public Health but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Norwegian Institute of Public Health and The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IH had the day-to-day responsibility of the article, did the analysis, wrote the first manuscript and coordinated the editing of the article. JGB contributed in designing the study and choosing analysis and participated in writing the manuscript. Reviewed and revised the manuscript. MH contributed in designing the study and in choosing analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript and participated in writing the manuscript. LT contributed in designing the study and in choosing analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript. TR contributed in designing the study and in choosing analysis, reviewed and revised the manuscript. EY contributed to the interpretation of data, revising the manuscript. HN contributed in discussing the analytical approach, reviewed and revised the manuscript. SS contributed in designing the study and participated in analysing and choosing, statistics. Reviewed and revised the manuscript. She approved the final draft before submitting. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from mothers before inclusion in MoBa. The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Protection Authority approved the linkage of NorPD and MoBa with reference number: 2012/570.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Shows the questions concerning medication use from the Norwegian Mother and Child cohort study questionnaire Q4 (6 months of age) and Q5 (18 months of age). (DOCX 971 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Holdø, I., Bramness, J.G., Handal, M. et al. Hypnotics use in children 0–18 months: moderate agreement between mother-reported survey data and prescription registry data. J of Pharm Policy and Pract 10, 28 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-017-0117-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40545-017-0117-7