Abstract

Background

Density is an important wood property due to its correlation with other wood properties such as stiffness and pulp yield, as well as being central to the accounting of carbon sequestration in forests. It is influenced by site, silviculture, and genetics, and models that predict the variation in wood density within and among trees are required by forest managers so that they can develop strategies to achieve certain wood density targets. The aim of the study presented here was to develop a wood density model for radiata pine (Pinus radiata D. Don) growing in New Zealand.

Methods

The model was developed using an extensive historical dataset containing wood density values from increment cores and stem discs that were obtained from almost 10,000 trees at over 300 sites. The model consists of two sub-models: (1) a sub-model for predicting the radial variation in breast-height wood density and (2) a sub-model for predicting the distribution of density vertically within the stem.

Results

The radial variation in breast-height wood density was predicted as a function of either ring number or both ring number and ring width, with the latter model better accounting for the effects of stand spacing. Additional model components were also developed in order to convert from annual ring density values to a whole-disc density, predict log density from disc densities, and account for the variation in wood density among individual trees within in a stand. The model can be used to predict the density of discs or logs cut from any position within a tree and can utilise measured outerwood density values to predict the density by log height for a particular stand. It can be used in conjunction with outerwood density to predict wood density distributions by logs for stands of any specified geographic location and management regime and is designed to be able to incorporate genetic adjustments at a later stage.

Conclusions

The analysis has confirmed and quantified much of the previous knowledge on the factors that affect the variation in wood density in radiata pine, particularly the influences of site factors and silviculture. It has also quantified the extent and patterns of variation in wood density within and among trees.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Density is an important wood property that affects the performance of solid wood products, pulp and paper, and some panel products (Kibblewhite 1984; Panshin and de Zeeuw 1980; Xu et al. 2004). It is also an important determinant of carbon sequestration in forests. Radiata pine (Pinus radiata D. Don) is the main commercial forestry species in New Zealand and is grown on a wide range of soil types and under differing climatic conditions, particularly with respect to temperature and rainfall. Past research in radiata pine growing in New Zealand established that there are significant regional trends in wood density, related to environmental factors such as mean annual temperature and soil nutrition (Beets et al. 2001; Beets et al. 2007; Cown 1999; Cown et al. 1991; Harris 1965; Palmer et al. 2013). In common with many other conifer species, radiata pine also exhibits a marked radial pattern whereby wood density increases from pith to bark (Cown 1980). In the vertical direction, whole-disc average wood density decreases with height up the stem largely because the number of rings decreases with height, meaning that proportionately more wood is contained within the lower density inner rings (Cown 1999).

Previous research has also investigated the effects of forest management practices, such as thinning, pruning and rotation age, and genetic differences on wood density (Burdon and Harris 1973; Burdon and Low 1992; Cown 1973, 1974, 1999; Cown and McConchie 1981, 1982; Cown et al. 1992). These studies have reported a positive correlation between wood density and mean annual temperature and a weak negative correlation between growth rate and wood density. Silvicultural treatments have a lesser impact unless stands are suddenly released from intense competition by severe thinning or a nutritional deficiency is corrected by fertiliser application. In these cases, a noticeable drop in density can occur for a few years immediately after treatment (Cown 1973). However, forest management is still expected to have an effect on wood density by varying the proportion of corewood within a tree (Cown 1992).

Forest managers commonly use growth and yield models to predict the impact of different combinations of site, genetics, and silviculture on volume and log product outturn (Weiskittel et al. 2011). There is also a demand to be able to predict the impacts of these factors on wood density as some log grades have a density requirement, often as a proxy for wood stiffness. For example, forest managers want to be able to determine what genetic stock and silvicultural regime (i.e., combination of spacing, thinning, and rotation length) are needed to achieve a particular wood density target for a given site. There are a number of examples of modelling systems that have been developed to link forest growth and timber quality in a range of species (Gardiner et al. 2011; Houllier et al. 1995; Peng and Stewart 2013), but a comprehensive modelling system does not exist for radiata pine wood properties. In New Zealand, an empirical model called STANDQUA was developed in the mid-1990s that enabled within-tree patterns of radiata pine wood density to be estimated from breast-height core samples and the future log-level wood density to be predicted (Tian and Cown 1995; Tian et al. 1995). More recently, a model was developed by Beets et al. (2007) to predict the density of annual growth sheaths in order to estimate carbon sequestration.

Both of these previous radiata pine wood density models were developed using various subsets of the extensive data that have been collected in numerous published and unpublished studies over many years. More comprehensive analyses of these data are required along with the development of models that enable forest managers to predict how different combinations of site, silviculture, and genetics affect wood density. Such analyses and new model development has been undertaken in three phases: (1) the development of a model to predict the spatial variation in breast-height outerwood density (i.e., basic density of the outer five growth rings or outer 50 mm); (2) the development of a model to predict the variation in wood density within a tree and among trees within a stand given a measured or predicted value of breast-height outerwood density; and (3) the incorporation of the effects of genetic gain for wood density into the model.

The results from the first phase of the analysis were presented in Palmer et al. (2013). They developed the concept of a wood density index, which is somewhat analogous to site index in growth and yield analysis as it uses a common base age to account for the known variation in wood density with age. The wood density index is defined as the breast-height outerwood density of 20-year-old radiata pine trees with silvicultural and genetic characteristics typical of stands planted in the 1990s. Across New Zealand, this wood density index was shown to be positively associated with mean annual air temperature, with higher values of wood density found in the warmer northern latitudes (Palmer et al. 2013). In this paper, we present analyses of both the intra-stem variation in wood density and the variation in density among trees within a stand. These analyses were used to develop a model that can be linked to the site-level model developed by Palmer et al. (2013) and also to growth and yield modelling systems (West et al. 2013). This enables investigation of the effects that factors such as rotation age and tree spacing have on within-tree patterns of wood density and the resulting whole-stem average density. Genetic effects can also be included in the modelling system using adjustments to the wood density index. The derivation of these genetic adjustments is described in a separate paper (Kimberley, MO, Moore, JR, & Dungey, HS (in review). Modelling the effects of genetic improvement on radiata pine wood density. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science).

Methods

Description of datasets used in the analyses

Data from a large number of historic studies were used to develop the within-tree density model. These data were of two main forms: (1) radial profiles of basic density at breast-height and (2) vertical profiles of whole-disc average density. Data on the radial profile of wood density were available from breast-height samples that had been collected from radiata pine stands throughout New Zealand. A total of 336 sites were sampled and approximately 30 trees were typically sampled at each site (Table 1). Data for 250 of these sites were collected in the wood properties survey undertaken by Cown et al. (1991). Wood density was assessed from 5-mm diameter increment cores in five-ring sections from the pith outwards using the Maximum Moisture Content method (Smith 1954). At 219 of these sites, trees were also felled and discs were cut at breast-height (1.4 m above the base of the tree) and at 5-m intervals up the stem. Basic density was determined for the whole disc and five-ring groups cut from these discs using gravimetric techniques. X-ray densitometry data were available for 17 sites and eight spacing trials. These data were obtained from either the Silviscan instrument (Evans 2000), located at CSIRO in Melbourne, or Scion’s X-ray densitometer (Cown and Clement 1983) and included ring-level values of wood density and ring width.

Total tree height was generally not measured in these studies, which has presented some problems in previous analyses (e.g., Moore et al. 2014; Watt and Zoric 2010). However, it was possible to predict the total height of trees in many studies using the relationship between disc diameter and height up the stem at which the disc was sampled. For each tree, separate quadratic regression models were fitted to predict disc diameter as a function of height up the stem, and total tree height was then predicted by extrapolating these models to a diameter of zero. To ensure this procedure provided reliable predictions of tree height, the models were only fitted using discs cut at greater than 5-m height, as above this height, stem taper was found to be adequately approximated by a quadratic model. Furthermore, predictions were only made when the diameter of the uppermost disc was less than 200 mm and where the uppermost disc was sampled from at least 70 % of the predicted total tree height. This procedure made it possible to estimate total tree height at 150 of the 219 sites where disc samples had been collected at multiple heights up the stem. Relative height of each disc sample was then calculated as disc height divided by predicted total tree height.

Model development

Various component models were developed from this extensive database as described below. In most cases, a nonlinear mixed modelling approach was used with models fitted using the NLMIXED procedure in Version 9.3 of the SAS software (SAS Institute Inc. 2011).

Breast-height density by ring number

The radial variation in breast-height density was modelled as a function of ring number from pith (cambial age). The data used to develop this model consisted of breast-height density data measured in five-ring groups from 336 sites throughout New Zealand. Prior to fitting the model, values of wood density were averaged across all trees at each site for each five-ring group. The fitted model had the following form:

where D BH is the basic density of a five-ring group at breast-height, Ring is the midpoint ring number from the pith for this five-ring group, and a, b, c, d, and f are model parameters estimated from the data. Because wood density varies considerably between sites (Palmer et al. 2013), a normally distributed site-level random term with a mean of zero, L, was included in the model to account for local site effects. When the model is applied to predict wood density for a particular site it is calibrated using this local parameter L. This parameter can be obtained using either the wood density index map (Palmer et al. 2013) or a wood density measurement from a sample of trees of known age (see Appendix 1 for details).

Breast-height density by ring number and ring width

An alternative breast-height density model using ring width as its principal independent variable was fitted to densitometry data averaged by ring at each of 25 sites. Data from eight of these sites were obtained from spacing trials, with each trial consisting of several replicate plots covering a range of post-thinning stand densities. Several different model forms from the published literature (e.g., Gardiner et al. 2011) were examined, with the following final model form selected on the basis of goodness of fit to the data:

where D BH is the basic density of a given annual ring (Ring) at breast-height, Rwidth is the width of the annual ring (mm), a, b, c, d, and f are model parameters estimated from the data, and L is a normally distributed site-level random term with mean zero.

Disc density by height in the stem

By plotting whole-disc average density against relative height, it was apparent that this property exhibited a sigmoidal pattern with relative height, well-approximated by a cubic function. Therefore, a model with the following form was fitted to the data:

where D disc is the whole-disc average density, H is the relative height of the disc up the stem, and a, b, c, and d are model parameters estimated from the data. As with the radial density models, this model is calibrated for a particular site using a local parameter L.

Conversion between outerwood basic density and whole-disc average density

When linking the breast-height radial density models (given by either Eqs. (1) or (2)) with the model for predicting the variation in whole-disc average density with height up the stem (Eq. (3)), it is necessary to convert from a measure of the density of the outer five rings (outerwood basic density) to whole-disc average density at breast-height. The ratio of disc density to outerwood density would be expected to be close to one both at very young stand ages (e.g., at about age 6 years when the disc will consist of only about five annual rings) and very old stand ages (because the pith-to-bark density profile reaches an asymptotic value at a cambial age of approximately 20 years). This was modelled using the following nonlinear function:

where D disc is the whole-disc average density, D ow is the outerwood basic density, age is the stand age (years), and a, b, and c are model parameters.

Variation in outerwood density among individual trees in a stand

In order to quantify the tree-to-tree variation in outerwood basic density, we used data from 82 stands which were sampled using two or more cores per tree. With these data, it was possible to separate out the small-scale variability of cores within a tree from the general variation between trees using variance component analysis.

The first step in this analysis was to examine the form of the statistical distribution of outerwood density between trees. Secondly, the existence of any potential relationships between easily predicted tree characteristics and wood density were examined. More specifically, the potential relationship between DBH and outerwood density was investigated by calculating correlation coefficients between these two variables for each stand. Following this, between- and within-tree variance components were estimated for each stand. Stands were classified on the basis of mean basic density into the following classes: 300–350, 351–400, 401–450, 451–500, and 501–550 kg m−3, and the variance components were averaged across stands in each class. Variance components were expressed as coefficients of variation (i.e., standard deviation as a percentage of the mean).

Application of the model

The wood density models developed in this paper were designed to be coupled to growth and yield models, so that the effects of site, silviculture, and genetics on wood density can be predicted. The implementation of these models within Forecaster, which is the most widely used growth and yield prediction system for radiata pine in New Zealand (West et al. 2013), is described in detail in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2. To illustrate the utility of the models developed in this study, we used them to predict within- and among-tree variation in wood density for different radiata pine stands growing on four sites: the northern part of the North Island (Northland); the central North Island (CNI); the upper part of the South Island (Nelson); and the southern part of the South Island (Southland). Values of wood density index, site index (mean height of the 100 largest trees per hectare based on diameter at breast-height at age 20 years) and 300 index (a volume productivity index for radiata pine defined as the mean annual volume increment of a stand containing 300 stems ha−1 at age 30 years (Kimberley et al. 2005)) were obtained from the relevant geospatial layers (Palmer et al. 2013; Watt et al. 2010) and are given in Table 2. At each site, three different silvicultural regimes were simulated. These consisted of two different initial planting densities (500 and 1000 stems ha−1). Stands were then thinned when the trees reached a mean height of 10 m. A constant thinning ratio of 2.5:1 was used resulting in residual stand densities after thinning of 200 and 400 stems ha−1, respectively. In addition, an un-thinned stand established at an initial density of 1000 stems ha−1 was also simulated. For each stand, whole-log average density was predicted for up to eight logs from each stem (each log had a nominal length of 5 m) and for rotation lengths of 20, 30, and 40 years.

Results

Modelling radial variation in wood density at breast-height

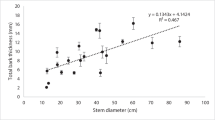

Basic density at breast-height showed a monotonic increase with increasing ring number from the pith, with the rate of increase diminishing after approximately 20 rings from the pith (Fig. 1). The model given by Eq. (1) explained 93 % of the variation in breast-height density for the dataset containing five-ring average values from 336 sites. This variation could be partitioned into variation between sites (which explained 45 % of the variation) and the pith-to-bark trend described by the model (which explained a further 48 % of the variation). Parameter estimates for the model are given in Table 3, and a comparison of model predictions against the five-ring average density values are shown in Fig. 1.

Pith-to-bark radial trend in breast-height wood density. Black dots correspond to mean densities by five-ring group at each site. The black lines show the density predicted by model 1 for an average site (middle solid line, L = 0) and for sites at the 5th and 95th percentiles (lower and upper dashed lines, L = −34.6 and L = +34.6, respectively)

Although the model given by Eq. (1) performed well in general, it did not explicitly account for the effects of stand stocking on wood density. For example, in one of the spacing trials in the dataset located in Tarawera Forest (near Rotorua in the central North Island), basic density at ring ten was approximately 400 kg m−3 at a stand density of 200 stems ha−1 but almost 500 kg m−3 at a stand density of 2000 stems ha−1 (Fig. 2). There was a strong negative linear relationship between the natural logarithm of ring width and basic density in this trial, with ring width seemingly able to explain the differences in basic density between the spacing treatments (Fig. 3). Across the 25 sites for which data on ring width and density were available, there was also a strong negative relationship between the natural logarithm of ring width and basic density (Fig. 4). However, ring width did not explain site differences in basic density. For this dataset, the site effects explained 63 % of the variation in basic density, while the model given by Eq. (1) explained 88.7 % of the variation. A model using the natural logarithm of ring width in combination with site (i.e., using a local parameter L) performed better than Eq. (1), explaining 91.5 % of the variation in basic density. However, the model given by Eq. (2) (which included both ring width and ring number as independent variables) explained 93.1 % of the variation in ring-level basic density. Parameter estimates for this model are given in Table 3.

Modelling vertical variation in whole-disc average density along a tree stem

The data used to model longitudinal variation in whole-disc average density consisted of measurements of disc diameter and density made at approximately 5-m intervals in trees from stands at 219 sites throughout New Zealand. By plotting disc density against relative height, it was apparent that density has a sigmoidal pattern with relative height well-approximated by a cubic function (Fig. 5) and was modelled using Eq. (3). In this model, 45.4 % of the total variation in density between all discs in the dataset was due to differences among sites (i.e., the L parameter) and the model explained 73.2 % of the total variation in whole-disc average density. This implied that the vertical pattern predicted by the model explained an additional 27.8 % of the variation. Equation (3), which was fitted using absolute height as the independent variable, explained 71.0 % of the variation, indicating that relative height was a slightly better predictor of whole-disc average density than absolute height. Furthermore, it was obvious when examining plots of density versus absolute and relative height (data not shown) that the vertical trend of whole-disc average density was more consistent between sites when using relative height as the independent variable. Parameter estimates for the model given by Eq. (3) are given in Table 3, and the model is shown plotted against the data in Fig. 5.

Variation in whole-disc density with relative height up the stem. The grey lines are smoothing curves fitted to the disc densities from each of 150 sites. The black lines show disc density predicted by model 3 for an average site (middle line, L = 0) and for sites at the 5th and 95th percentiles (lower and upper dashed lines, L = −59.3 and L = +59.3, respectively)

Converting outerwood density to whole-disc average density

The ratio of whole-disc average density to outerwood density at breast-height was found to be approximately constant with stand age, averaging 0.942 with standard error 0.0032 (Fig. 6). A simple conversion to whole-disc average density could, therefore, be achieved by multiplying the outerwood density by this mean value. However, a slightly better result was obtained using Eq. (4) with parameter estimates given in Table 3.

Variation in the ratio between disc density and density of the outer five rings at breast-height with stand age. The red line shows Eq. (4)

Variation in outerwood density among individual trees within a stand

The distribution of outerwood density among trees within a stand was approximately normal. For example, the distribution of breast-height outerwood density is shown in Fig. 7 for stands grouped into low and high density classes. Overall, the variation among trees expressed as a coefficient of variation averaged 6.46 % and did not vary with mean density. In contrast, within-tree variation (i.e., variation between multiple breast-height outerwood cores taken from the same tree) increased with mean density, or equivalently, with age (Fig. 8). This implies that as trees become larger and older, the variation in outerwood density at different locations around the stem increases. However, more importantly, the variation in mean density does not increase when expressed as a percentage of the mean density. There was almost no relationship between tree diameter and wood density within a stand. The average of the correlation coefficients calculated for each stand was −0.07, and the individual correlation coefficients were symmetrically distributed about this mean.

Application of the model

The values of log average density predicted for the four sites followed the expected pattern given the differences in wood density index (Fig. 9). For the stand growing on a site in Northland, whole-log average wood density was 410 kg m−3 at age 30 years. Conversely, whole-log average wood density for the stand growing at a site in Southland was 325 kg m−3 at the same age. The effect of silvicultural regime was not as large as the effect of site, although the stands thinned to 200 stems ha−1 typically had a whole-log average wood density that was 18–30 kg m−3 lower than stands thinned to 400 stems ha−1. The difference in wood density between un-thinned stands and stands thinned to 400 stems ha−1 was much less, typically 5–10 kg m−3. Whole-log average density decreased with increasing log height up the stem. At a stand age of 30 years, it was approximately 20 kg m−3 lower in the fifth log than in the butt log at the Southland site and 50 kg m−3 lower at the Northland site. For an equivalent log height, there was an increase in log average density of 5–8 kg m−3 for each 10-year increase in rotation length.

Discussion

The models described in this paper represent a comprehensive analysis of the data collected for radiata pine over the past 50 years. While the general within- and among-stem trends in radiata pine wood density are generally well-known (Cown 1973, 1974; Cown and McConchie 1981, 1982; Cown et al. 2002; Palmer et al. 2013), this is the first time that a complete model linking tree growth and wood density has been developed for the species. This modelling system will allow the relative effects of environmental, silvicultural, and genetic effects on radiata pine wood density to be accurately quantified. The breast-height radial density model linked to the height-within-stem density model can predict densities of logs cut from any position within a stem and at any age. When linked to a growth modelling system capable of predicting ring widths at any height, it is also possible to use these models to estimate density by annual ring and height within stem. This can be achieved by estimating the disc densities annually, and using the predicted ring width at any height, to derive the density of each ring. Finally, the distribution of individual logs cut from different stems in a stand is modelled on the assumption that they are normally distributed with a fixed coefficient of variation. Model implementation details are explained in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2.

The purpose of the analysis reported here was to investigate the variation in wood density within and among trees within a stand. However, analysis of the breast-height five-ring and the whole-disc datasets showed that approximately 45 % of the variation in these datasets was due to differences between sites. These site effects are incorporated into the model through a local parameter, which can be estimated from density samples collected from trees or based on the location of the stand, from the national wood density index map described by Palmer et al. (2013). Differences in wood density among sites have been shown to be due to factors such as temperature, rainfall, and soil fertility (Beets et al. 2001; Beets et al. 2007; Cown et al. 1991; Harris 1965; Palmer et al. 2013). While it is conceivable that the effect of these factors on wood density might be explained by ring width as they are known to also affect productivity (Watt et al. 2010), our analysis showed that even after accounting for ring width, there was still a large amount of unexplained site-level variation (Fig. 4). Therefore, the wood density model given by Eq. (2) that included ring width as an independent variable also requires a local parameter to account for site differences.

The negative relationship between ring width and wood density, after accounting for ring number, is consistent with findings in studies on other species (e.g., Gardiner et al. 2011; Jozsa and Middleton 1994; Jyske et al. 2008; Kantavichai et al. 2010; Zhang 1998). This apparent relationship between wood density and ring width has been the subject of some controversy in the scientific literature (e.g., Sutton and Harris 1974; Wimmer and Downes 2003) where, in some cases, the negative correlation between ring number and ring width has not been accounted for. Our results showed that ring width can be used to explain the effect of growth differences on wood density among stands growing at the same site but not differences among sites. In fact, the negative relationship between ring width and wood density would suggest that lower density wood would be found on those sites where radial growth rate (all other factors being equal) is higher. However, for the same silvicultural regime both wood density and ring width are higher on warmer northern sites than on cooler southern sites (Palmer et al. 2013; Watt et al. 2010). A previous study by Cown and Ball (2001) showed that latewood percentage was the main factor associated with regional variation in wood density. More detailed investigation is required in order to better understand the relationship between ring width and wood density, particularly how within-ring density components (i.e., earlywood density, latewood density, and latewood percentage) are affected by ring width. Studies in Norway spruce (Picea abies Karst.) have shown that the partial correlation between ring width and density, after controlling for latewood percentage, is much lower than the simple correlation (Jyske et al. 2008; Wimmer and Downes 2003). Furthermore, the correlation between ring width and wood density fluctuates between years depending on climatic and silvicultural factors (Wimmer and Downes 2003).

This level of variation in wood density among trees within a stand confirms the results from previous studies (Cown 1999; Cown et al. 1991). Overall, there was no evidence of a correlation between wood density and diameter at breast-height. However, in a few of the stands there was a weak negative correlation between these traits. A closer examination of the few stands that showed a significant association between DBH and density indicated that this occurred only in older, highly stocked stands, containing small suppressed trees. Such trees tended to be of higher than average density producing a weak negative correlation between density and DBH in these stands. It is important to note that this result applies to individual trees within a stand, not to stands growing at different stand densities at the same site, where mean wood density is related to mean ring width. While this study found that there was generally no phenotypic correlation between wood density and diameter at breast-height, most studies in radiata pine have found that there is a negative genetic correlation between these two traits (Wu et al. 2008). The wood density model is able to assist tree breeders who want to be able to predict the implications of early selections on later age wood properties and whole-log density. At present, tree breeders rely on knowledge of age-age correlations to assist with this (Kumar and Lee 2002; Li and Wu 2005).

The radial and vertical trends in wood density were broadly similar to those observed in other studies (Burdon et al. 2004; Cown et al. 1991). Previous research has suggested that the gradients of wood properties found in radiata pine are underpinned by differences in the rate of cambial cell division, differences in the rate and duration of tracheid wall thickening, and differences in gene expression (Cato et al. 2006). In the radial direction, wood density increased rapidly with increasing ring number from the pith before reaching a quasi-asymptotic value such that little change in density occurred after approximately ring 20. This typical radial pattern has frequently been used to determine the extent of the corewood zone, which is defined as the region in which the radial rate of change in wood properties is greatest (Lachenbruch et al. 2011; Zobel and Sprague 1998). In radiata pine, corewood has typically been defined as the innermost ten growth rings from the pith (Burdon et al. 2004; Cown 1992), although a threshold density of 400 kg m−3 has also been proposed (Cown 1992). The results from the current study show that wood density is still increasing rapidly with cambial age at ten rings from the pith, suggesting that the arbitrary ten ring definition may be inadequate. However, other properties, such as microfibril angle, also need to be considered when determining the age of transition from corewood to outerwood (Mansfield et al. 2009). The models developed in this study can be used to further investigate the extent of the corewood zone, particularly if defined based on a wood density threshold, and how this is affected by different factors, such as environment and silviculture.

Conclusions

An extensive database of radiata pine wood density data collected over 50 years of research has enabled models to be generated to predict within-tree, within-stand, and among-stand variation in wood density. These models can be linked to growth and yield models so that forest managers can predict the impacts of factors such as site, silvicultural regime, and genetics on wood density. The research here has confirmed and quantified much of the previous knowledge on the factors that affect the variation in wood density in radiata pine.

References

Beets, PN, Gilchrist, K, & Jeffreys, MP. (2001). Wood density of radiata pine: effect of nitrogen supply. Forest Ecology and Management, 145, 173–80.

Beets, PN, Kimberley, MO, & McKinley, RB. (2007). Predicting wood density of Pinus radiata annual growth increments. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 37(2), 241–66.

Burdon, RD, & Harris, JM. (1973). Wood density in radiata pine clones on four different sites. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 3(3), 286–303.

Burdon, RD, & Low, CB. (1992). Genetic survey of Pinus radiata. 6. Wood properties: variation, heritabilities, and interrelationships with other traits. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 22, 228–45.

Burdon, RD, Kibblewhite, RP, Walker, JCF, Megraw, RA, Evans, R, & Cown, DJ. (2004). Juvenile versus mature wood: a new concept, orthogonal to corewood versus outerwood, with special reference to Pinus radiata and P. taeda. Forest Science, 50(4), 399–415.

Cato, S, McMillan, L, Donaldson, L, Richardson, T, Echt, C, & Gardner, R. (2006). Wood formation from the base to the crown in Pinus radiata: gradients of tracheid wall thickness, wood density, radial growth rate and gene expression. Plant Molecular Biology, 60(4), 565–81. doi:10.1007/s11103-005-5022-9.

Cown, DJ. (1973). Effects of severe thinning and pruning treatments on the intrinsic wood properties of young radiata pine. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 3, 379–89.

Cown, DJ. (1974). Comparison of the effects of two thinning regimes on some wood properties of radiata pine. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 4, 540–51.

Cown, DJ. (1980). Radiata pine: wood age and wood property concepts. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 10, 504–7.

Cown, DJ. (1992). Corewood (juvenile wood) in Pinus radiata—should we be concerned? New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 22(1), 87–95.

Cown, DJ. (1999). New Zealand pine and Douglas-fir: suitability for processing. (FRI Bulletin 216). Rotorua: New Zealand Forest Research Institute.

Cown, DJ, & Ball, RD. (2001). Wood densitometry of 10 Pinus radiata families at seven contrasting sites: influence of tree age, site, and genotype. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 31(1), 88–100.

Cown, DJ, & Clement, BC. (1983). A wood densitometer using direct scanning with X-rays. Wood Science and Technology, 17(2), 91–9.

Cown, DJ, & McConchie, DL. (1981). Effects of thinning and fertiliser application on wood properties of Pinus radiata. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 11, 79–91.

Cown, DJ, & McConchie, DL. (1982). Rotation age and silvicultural effects on wood properties of four stands of Pinus radiata. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 12(1), 71–85.

Cown, DJ, McConchie, DL, & Young, GD. (1991). Radiata pine wood properties survey. (FRI Bulletin 50, revised edition). Rotorua, New Zealand: Ministry of Forestry, Forest Research Institute.

Cown, DJ, Young, GD, & Burdon, RD. (1992). Variation in wood characteristics of 20-year-old half-sib families of Pinus radiata. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 22(1), 63–76.

Cown, DJ, McKinley, RB, & Ball, RD. (2002). Wood density variation in 10 mature Pinus radiata clones. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 32(1), 48–69.

Evans R. (2000). SilviScan and its future in wood quality assessment. Melbourne, Australia: 54th APPITA Annual General Conference 2000, (pp. 271–4). APPITA.

Gardiner, B, Leban, J-M, Auty, D, & Simpson, H. (2011). Models for predicting wood density of British-grown Sitka spruce. Forestry, 84(2), 119–32. doi:10.1093/forestry/cpq050.

Harris, JM. (1965). A survey of the wood density, tracheid length and latewood characteristics of radiata pine grown in New Zealand. (FRI Technical Paper 47). Rotorua: New Zealand Forest Service, Forest Research Institute.

Houllier, F, Leban, J-M, & Colin, F. (1995). Linking growth modelling to timber quality assessment for Norway spruce. Forest Ecology and Management, 74, 91–102.

Jozsa, LA, & Middleton, GR. (1994). A discussion of wood quality attributes and their practical applications. Special publication no. SP-34). Vancouver: Forintek Canada Corp.

Jyske, T, Mäkinen, H, & Saranpää, P. (2008). Wood density within Norway spruce stems. Silva Fennica, 42(3), 439–55.

Kantavichai, R, Briggs, D, & Turnblom, E. (2010). Modeling effects of soil, climate, and silviculture on growth ring specific gravity of Douglas-fir on a drought-prone site in Western Washington. Forest Ecology and Management, 259(6), 1085–92. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2009.12.017.

Kibblewhite, RP. (1984). Radiata pine wood and kraft pulp quality relationships. Appita, 37(9), 741–7.

Kimberley, M, West, G, Dean, M, & Knowles, L. (2005). The 300 index—a volume productivity index for radiata pine. New Zealand Journal of Forestry, 50(2), 13–8.

Kumar, S, & Lee, J. (2002). Age-age correlations and early selection for end-of-rotation wood density in radiata pine. Forest Genetics, 9(4), 323–30.

Lachenbruch, B, Moore, JR, & Evans, R. (2011). Radial variation in wood structure and function in woody plants, and hypotheses for its occurrence. In FC Meinzer, B Lachenbruch, & TE Dawson (Eds.), Size- and age-related changes in tree structure and function (pp. 121–64). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Li, L, & Wu, HX. (2005). Efficiency of early selection for rotation-aged growth and wood density traits in Pinus radiata. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 35(8), 2019–29. doi:10.1139/x05-134.

Mansfield, SD, Parish, R, Di Lucca, CM, Goudie, J, Kang, KY, & Ott, P. (2009). Revisiting the transition between juvenile and mature wood: a comparison of fibre length, microfibril angle and relative wood density in lodgepole pine. Holzforschung, 63(4), 449–56.

Moore, JR, Cown, DJ, & McKinley, RB. (2014). Modelling microfibril angle variation in New Zealand-grown radiata pine. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 44:25. doi:10.1186/s40490-014-0025-4.

Palmer, DJ, Kimberley, MO, Cown, DJ, & McKinley, RB. (2013). Assessing prediction accuracy in a regression kriging surface of Pinus radiata outerwood density across New Zealand. Forest Ecology and Management, 308, 9–16.

Panshin, AJ, & de Zeeuw, C. (1980). Textbook of wood technology (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Peng, M, & Stewart, JD. (2013). Development, validation, and application of a model of intra- and inter-tree variability of wood density for lodgepole pine in western Canada. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 43(12), 1172–80. doi:10.1139/cjfr-2013-0208.

SAS Institute Inc. (2011). Base SAS® 9.3 Procedures guide. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc.

Smith, DM. (1954). Maximum moisture content method for determining specific gravity of small wood samples. Madison, WI, USA: United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory. Report 2014.

Sutton, WRJ, & Harris, JM. (1974). Effect of heavy thinning on wood density in radiata pine. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 4, 112–5.

Tian, X, & Cown, DJ. (1995). Modelling of wood properties in New Zealand. In K Klitscher, DJ Cown, & L Donaldson (Eds.), Wood quality workshop 95. FRI bulletin 201 (pp. 72–81). Rotorua, New Zealand: Forest Research Institute.

Tian, X, Cown, DJ, & McConchie, DL. (1995). Modelling of radiata pine wood properties. Part 2: wood density. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 25(2), 214–30.

Watt, MS, & Zoric, B. (2010). Development of a model describing modulus of elasticity across environmental and stand density gradients in plantation-grown Pinus radiata within New Zealand. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 40(8), 1558–66.

Watt, MS, Palmer, DJ, Kimberley, MO, Hock, K, Payn, TW, & Lowe, DJ. (2010). Development of models to predict Pinus radiata productivity throughout New Zealand. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 40(3), 488–99.

Weiskittel, AR, Hann, DW, Kershaw, JA, Jr, & Vanclay, JK. (2011). Forest growth and yield modeling. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

West, GG, Moore, JR, Shula, RG, Harrington, JJ, Snook, J, Gordon, JA, & Riordan, MP. (2013). Forest management DSS development in New Zealand. In J Tucek, R Smrecek, A Majlingova, & J Garcia-Gonzalo (Eds.), Implementation of DSS tools into the forestry practice (pp. 153–163). Slovakia.: Technical University of Zvolen.

Wimmer, R, & Downes, GM. (2003). Temporal variation of the ring width-wood density relationship in Norway spruce grown under two levels of anthropogenic disturbance. IAWA Journal, 24(1), 53–61.

Wu, HX, Ivković, M, Gapare, WJ, Matheson, AC, Baltunis, BS, Powell, MB, & McRae, TA. (2008). Breeding for wood quality and profit in Pinus radiata: a review of genetic parameter estimates and implications for breeding and deployment. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science, 38(1), 56–87.

Xu, P, Donaldson, L, Walker, J, Evans, R, & Downes, G. (2004). Effects of density and microfibril orientation on the vertical variation of low-stiffness wood in radiata pine butt logs. Holzforschung, 58(6), 673–7.

Zhang, SY. (1998). Effect of age on the variation, correlations and inheritance of selected wood characteristics in black spruce (Picea mariana). Wood Science and Technology, 32, 197–204.

Zobel, BJ, & Sprague, JR. (1998). Juvenile wood in forest trees. Berlin: Springer.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the analysis of these data was provided by Future Forests Research Ltd. We would like to thank numerous current and former colleagues who collected density samples over many years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MOK developed the modelling approach, undertook the data analysis, and contributed to writing the manuscript. DJC and RBMcK assembled the wood density data and contributed to the interpretation of the results and writing of the manuscript. JRM contributed to writing the manuscript, and LJD undertook the forecaster analysis. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Implementation of models within a growth and yield prediction system

The density models use local parameters to calibrate them to particular sites or stands. For the breast-height radial density models, this parameter is calculated from the density at a specified ring number. This can be obtained either from a measurement of density (e.g., from outerwood density cores taken from sample trees), or more commonly, using the map showing national variation in wood density index developed by Palmer et al. (2013). For the breast-height radial density model given by Eq. (1), the local parameter is calculated by solving Eq. (1) for L, such that

The wood density index is defined as breast-height outerwood density (density of the outermost five rings) for a 20-year-old stand. The mean ring number for an outerwood sample taken from breast-height in a 20-year-old stand is calculated using the following equation:

where SI is the site index (mean top height (m) of a stand at a reference age of 20 years). The bracketed term in this equation is the number of years for a stand growing on a site with a given site index to achieve a mean height of 1.4 m. It was derived by running the 300 index growth model (Scion, unpublished data) for a range of site indices and using a quadratic function to model the relationship between site index and the age at which mean height reached 1.4 m.

For the breast-height radial density model given by Eq. (2), the local parameter is calculated by solving Eq. (2) for L such that

Equation (A3) requires a measurement of both wood density and ring width at a known ring number. These could be obtained from outerwood cores taken from a sample of trees, in which case the mean ring number and ring width of the density sample would be used. However, if the national wood density index map is used to calibrate the model, it is necessary to use a ring width that is compatible with the site selected on this map. Because the model given by Eq. (2) is intended to be used in conjunction with the 300 index growth model, the 300 index (Kimberley et al. 2005) and site index must be either specified by the user or estimated from a growth measurement. In either case, Ring is estimated using Eq. (A2), while ring width is calculated using the following equation:

where I 300 is the 300 index (m3 ha−1 yr−1). This equation was developed by predicting mean ring width of the five outermost growth rings at breast-height for a 20-year-old stand using the 300 index growth model. The model was run for sites where the 300 index ranged from 15 to 40 m3 ha−1 year−1 and site index ranged from 20 to 40 m. The silvicultural regime that these stands were grown under was assumed to be typical of those contributing to the database used to develop the wood density index geospatial layer (i.e., an initial planting density of 833 stems ha−1, pruned to 6 m and thinned to a residual stand density of 400 stems ha−1 at age 9 years).

Once the local parameter has been estimated, the radial profile of basic density at breast-height can be predicted using the models given by either Eq. (1) or Eq. (2). When the model given by Eq. (2) is used in conjunction with a growth model, the width of each annual ring is predicted by the growth model, and these can be used to estimate the whole-disc density at breast-height as an area-weighted average of the ring-level values. When the model given by Eq. (1) is used, breast-height disc density is estimated using Eq. (4). The model given by Eq. (3) is then used to predict whole-disc average density at any position along the stem. This requires a local parameter, which is calculated by solving Eq. (3) for L, such that

where D disc,BH is the breast-height disc density, \( h=\frac{1.4}{H_{\mathrm{total}}-0.4} \), and H total is total tree height (m).

Appendix 2

Derivation of a method to calculate whole-log density from disc density

The simplest approach would be to take the arithmetic average of the density of the disc at each end of the log. However, as logs are usually tapered, slightly more weight should be given to the density of the disc at the large end of the log, compared with the disc from the small end. If both disc diameter and density vary linearly with distance along a log (a reasonable assumption over the length of a typical log), the average density of the log is

where: D disc,L and D disc,S are the whole-disc average density values at the large and small ends of the log, respectively, and W is the weighting factor. This weighting factor is a function of the ratio of small- to large-end diameter of the log (SED/LED):

This result can be established using basic calculus. Without loss of generality, assume that log length is 1 and large-end diameter (LED) is 1. Let R = SED/LED and let the whole-disc densities of each end of log be D disc,L and D disc,S. The density at any position x along the log is D disc,L − x(D disc,L − D disc,S) and the diameter of the log at position x is 1 − (1 − R)x. The density of the log is the integral over the length of the log of density multiplied by the square of the diameter, divided by the integral of the diameter, i.e.,

The solution to this integral (steps not shown) is:

Using the above result, log density will be obtained in the growth model implementation of the density model using the predicted diameter of the stem at each end of the log. In a stand-alone version of the density model, the weight W could be calculated by making reasonable assumptions on the values of log diameter, length, and taper. As an example, in a 5-m log with 400-mm SED and 6-mm/m taper, the value of W calculated using Eq. (A7) is 0.512. It can be seen from this example that a simple average of the two log end densities (i.e., assuming W = 0.5) would generally be adequate.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kimberley, M.O., Cown, D.J., McKinley, R.B. et al. Modelling variation in wood density within and among trees in stands of New Zealand-grown radiata pine. N.Z. j. of For. Sci. 45, 22 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-015-0053-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-015-0053-8