Abstract

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a neurodegenerative disease associated with repetitive traumatic brain injury (TBI). CTE is generally found in athletes participating in contact sports and military personnel exposed to explosive blasts but can also affect civilians. Clinically and pathologically, CTE overlaps with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a term mostly used in a clinical context. The histopathology of CTE is defined by the deposition of hyperphosphorylated tau protein in neurons and astrocytes preferentially with perivascular distribution and at the depths of the cortical sulci. In addition to hyperphosphorylated tau, other pathologic proteins are deposited in CTE, including amyloid β (Aβ), transactive response (TAR) DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) and α-synuclein. However, the coexistence of prion disease in CTE has not been observed. We report three cases of histopathologically validated CTE with co-existing sporadic prion disease. Two were identified in a cohort of 55 pathologically verified cases of CTE submitted to the CTE Center of Boston University. One was identified among brain tissues submitted to the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center of Case Western Reserve University. The histopathological phenotype and properties of the abnormal, disease-related prion protein (PrPD) of the three CTE cases were examined using lesion profile, immunohistochemistry, electrophoresis and conformational tests. Subjects with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) matched for age, PrP genotype and PrPD type were used as controls. The histopathology phenotype and PrPD properties of the three CTE subjects showed no significant differences from their respective sCJD controls suggesting that recurring neurotrauma or coexisting CTE pathology did not detectably impact the prion disease phenotype and PrPD conformational characteristics. Based on the reported incidence of sporadic prion disease, the detection of two cases with sCJD in the CTE Center series of 55 CTE cases by chance alone would be highly unlikely (p = 8.93*10− 6). Nevertheless, examination of a larger cohort of CTE is required to conclusively determine whether the risk of CJD is significantly increased in patients with CTE.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

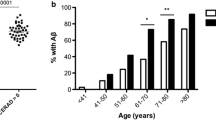

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is currently defined as a distinctive neurodegenerative condition associated with repetitive, and rarely single, traumatic brain injury (TBI) [29, 30]. CTE is found among athletes practicing contact sports and military veterans but ordinary civilians with history of head trauma are equally exposed [30]. The clinical features vary but most often include combinations of cognitive, mood, behavioral and motor symptoms and signs [29]. Some individuals with pathologically verified CTE have been diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during life as both conditions share neuropsychiatric symptoms consistent with frontal lobe dysfunction [18, 27, 30, 32, 56]. CTE is considered to be a primary tauopathy as the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (p-tau) in neurons and astrocytes around small blood vessels, predominantly at the depths of the cerebral cortical sulci [30, 55]. However, pathologies related to the accumulation of proteins associated with other neurodegenerative diseases are frequently seen, particularly in the context of increased age [55]. They include amyloid β (Aβ), a hallmark of Alzheimer disease, α-synuclein, a feature of Parkinson’s and Lewy body disease, and TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), typical of frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [31]. Furthermore, TBI of any magnitude significantly increases the risk of dementia [2], although it is unclear whether TBI elevates the risk for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [20, 61]. Recent studies also show an increased risk for Parkinson’s and Lewy body disease after TBI [1, 13] along with FTLD and motor neuron disease including ALS [28, 30]. These observations provide compelling evidence that neurotrauma creates biological conditions favoring not only CTE but also other morbidities associated with protein misfolding, the critical step shared by most neurodegenerative diseases [10].

Prion diseases are currently the archetype of protein misfolding disease. They have best exemplified the conformational basis of strain diversity and the correlation between genotype, strain characteristics and disease phenotype. Human prion diseases are characterized by a broad phenotypic heterogeneity, which is dictated not only by the various etiologies ̶ sporadic, inherited and acquired by infection ̶ but also by the variety of the underlying prion strains [14, 15]. In fact, the five distinct phenotypes or subtypes recognized in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) are associated with diverse prion strains (Additional file 1: Table S1) [8, 11, 14, 23, 41, 47, 51]. Furthermore, human prion strains may co-occur resulting in mixed phenotypes that reflect the representation of the corresponding strain [4, 8, 47]. Evidence indicates that codon 129 of the human prion protein (PrP) gene that harbors the common methionine (M)/valine (V) polymorphism, influences the formation of a specific prion strain which encrypts the disease phenotype [14, 15, 17, 57]. The co-occurrence of prion diseases with other age-related neurodegenerative disorders has been previously reported [6, 7, 16]. However, prion disease has not been previously reported as a comorbidity in CTE nor has it been found to be associated with head trauma [27, 62].

We investigated the presence of prion disease in 55 subjects with autopsy-proven CTE and found two prion-positive cases. A third case clinically diagnosed with PTSD and prion disease had been referred to the National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC). Neuropathological examination confirmed that all three subjects had the unique features of severe prion disease and CTE (henceforth, they are referred to as CTE cases 1–3). In all cases, the prion histopathological phenotype showed no significant variation from the typical phenotypes of the sCJD control subjects matched to the three CTE cases by PrP genotype and the abnormal disease-related PrP (PrPD) type. Similarly, conformational characteristics of the PrPD also matched those of the controls pointing to the homology of the strain characteristics. To our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the comorbidity of sCJD in CTE.

Materials and methods

Tissues and subjects

Frozen and fixed brain tissue from two subjects (hereafter indicated as case 1 and case 2) were obtained from a 55 cohort received from the Veterans Affairs-Boston University-Concussion Legacy Foundation (VA-BU-CLF) brain bank where they received the histopathological diagnosis of CTE. One subject (case 3) was acquired from the NPDPSC of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH; this case was found serendipitously but a subsequent search revealed no additional cases. Neither cases 1 or 2 had final clinical diagnoses that included a prion disease, although case 1 had a rapid decline in his last year consistent with possible CJD and case 2 was initially suspected as having CJD. During the illness, case 1 was treated for Parkinson’s disease. Case 3 was clinically diagnosed with PTSD, and, subsequently, with prion disease; thus case 3 was the only one to receive the final diagnosis of probable prion disease. Nine cases of sCJD that were matched to the study cases by sCJD subtype, sex, age at onset and disease duration were obtained from the NPDPSC (Additional file 1: Table S2). Post-mortem formalin-fixed brain tissues from the 53 additional subjects of the 55 cohort with pathologically verified CTE were also obtained from the CTE Center and examined for the presence of prion disease by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Molecular genetics

DNA was isolated from the frozen brain tissues and genotyping of PRNP coding region was performed as previously described [40].

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibodies (Abs) 3F4 to PrP residues 109–112 [21], SAF70 to PrP residues 156-162 (Cayman chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), 1E4 to PrP residues 97-108 (Cell Sciences, Canton, MA, USA) and 12B2 to PrP residues 89–93 [25]. Abs PHF-Tau (clone AT8) and α-syn (clone LB509) (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) as well as 4G8 (R. Kascsak at the N.Y.S. Institute for Basic Research) and TDP-43 (Cosmo Bio Co. LTD, Carlsbad, CA) were used for immunohistochemistry. Secondary Abs included the infrared Dye (IRDye) 800CW goat anti-mouse IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA), and the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG Ab (GE Healthcare, Life Sciences Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Histopathology, immunohistochemistry, Thioflavin S staining and lesion profiling

Histology and immunohistochemistry were performed essentially as earlier described with modifications [5, 6]. Histological sections from ten brain regions including frontal (FC), temporal (TC), parietal (PC), occipital (OC) and entorhinal cortices (EC), CA1 region of the hippocampus (HI), basal ganglia (BG), thalamus (TH), substantia nigra (SN) and cerebellum (CE) were examined to evaluate the severity and distribution of spongiform degeneration (SD) and gliosis. Lesion profiles were constructed from semi-quantitative scoring of SD and astrogliosis in the three CTE cases and their respective sCJD controls according to a modification of previous methods [22, 41]. Briefly, SD and astrogliosis were scored for severity in each brain region, and mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of the two lesions were plotted to generate a profile of brain lesion distribution for each case. IHC with the Ab 3F4 (1:1000) was carried out to determine presence, distribution and pattern of PrP deposition. In addition, IHC was carried out with Abs AT8 (1:200), 4G8 (1:3000), TDP-43 (1:7000) and α-syn (1:50) to p-tau, Aβ, TDP-43, and α-syn respectively. Thioflavin S staining was performed as previously described [6].

Western blot

Brain homogenate (BH) (10% w/v) were prepared on ice with lysis buffer (LB100) (100 mM Tris HCl pH 7.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate), and brought to pH 6.8 at 37 °C [36]. When indicated, BH were treated with 54 U/ml proteinase K (PK) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h (h). Protease digestion was stopped by adding 2 mM PMSF. Samples were mixed with equal volumes of 2× sample buffer (6% SDS, 8% 2-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 4 mM EDTA, 125 mM Tris HCl pH 6.8) and boiled for 10 min before loading. Protein samples (brain tissue equivalent 0.1–3 mg of wet tissue) were separated in 15% Criterion Tris-HCl polyacrylamide precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) and blotted into Immobilon-P membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) for 2 h at 60 V, blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-T (1× TBS with 0.1% Tween 20) and probed with the indicated Abs. Immunoblots were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce ECL plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) on Carestream Kodak BioMax films (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA) or with the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LICOR Biosciences) as described by the manufacturer.

PrPD conformational assays

The conformational stability and solubility assay (CSSA) [45] was performed as previously described [12]. Occipital cortex was used for case 1 and the frontal cortex for cases 2 and 3. Matching brain regions were used for respective sCJD control cases [sCJDMV1-2C (n = 3); sCJDMV2K-C (n = 3); sCJDMM1 (n = 3)]. Briefly, aliquots of BH (20% w/v) in 1× D-PBS were mixed with an equal volume of 2× LB 100 pH 8.0 (200 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 20 mM EDTA), incubated for 10 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C to eliminate tissue debris. The supernatant S1 was then subjected to high speed centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1 h and the resultant supernatant (S2) and pellet (P2) fractions were collected. The P2 were re-suspended in cold LB100 pH 8.0 and S2 stored at − 80 °C. To determine the denaturation rate of total PrPD, aliquots of the re-suspended P2 were diluted with an equal volume of guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl) to obtain final concentrations of GdnHCl ranging from 0 M to 4 M, and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C under gentle shaking. The samples were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 20 min at 22 °C. The pellets were re-suspended in 1× sample buffer by sonication and boiled for 10 min at 100 °C. In addition, the solubility features of the PK-resistant PrPD (resPrPD), were also determined in the same manner as described above for total PrPD with the exception that the P2 aliquots used for this procedure were digested with PK (5 U/ml) prior to incubation with GdnHCl. Finally, all samples were subjected to immunoblotting with 3F4. The automated estimation of PrP intensity at the different concentrations of GdnHCl was performed using the Odyssey application software V3.0 (LI-COR Biosciences). The curves of solubility, generated by the decreasing levels of PrPD as a function of the increasing concentrations of GdnHCl, were best fitted to a sigmoidal dose-response equation (GraphPad Prism, 7.0). For each given curve of solubility, the [GdnHCl]1/2, which represents concentration of GdnHCl required to solubilize 50% of PrPD, was determined. The mean [GdnHCl]1/2 values ± SEM were calculated and compared between groups.

The conformational stability immunoassay (CSI) was also performed according to previous procedures [4, 43, 64]. Aliquots of BH (10% w/v) in LB100 pH 8.0 were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to and the S1 was collected. 100 μl of S1 was diluted with an equal volume of GdnHCl to obtain a final concentrations ranging from 0 M to 4 M and incubated for 1.5 h at 22 °C. GdnHCl was subsequently removed by incubating each sample with an excess of 5-fold pre-chilled methanol overnight at − 20 °C followed by centrifugation at 17,200 × g for 30 min. Pellets were resuspended in 100 μl LB100 pH 8.0 by sonication. Each aliquot was digested with 5 U/ml PK for 1 h at 37 °C, reaction was terminated by addition of 2 mM PMSF. Samples were denatured and loaded onto 15% precast Tris HCl gels. PrP amounts at different GdnHCl concentrations were measured by Odyssey application software V3.0. The conformational stability of PrPD, evaluated as a function of PrPD remaining following exposure to increasing concentrations of GdnHCl was best fitted to a sigmoidal dose-response equation using Graphpad Prism. The mean [GdnHCl]1/2 values ± SEM were calculated and compared between respective groups.

Statistical analysis

Statistical testing was performed to assess the probability of the observed outcome (two prion disease cases in the cohort of 55 CTE subjects) by chance alone. Cohort person-years were counted by sex (all subjects were male) and 10-year age categories. To calculate expected prion disease cases, we multiplied the person-years by sex- and age group-specific US prion disease rates (excluding cases with known genetic or acquired etiology) derived from national surveillance, 2003–2015 (Maddox RA et al., 2018 unpublished results). Person-years were calculated from birth until death; although the true exposure would start at the first traumatic brain injury, professional athletes would likely have started playing contact sports at a young age and rates of sporadic prion diseases below age 20 years are negligible. After determining the expected count of prion disease cases, we used a Poisson distribution to determine the probability of observing two or more prion disease cases in the cohort. Since one or possibly both of these prion disease cases might not have been ascertained in national surveillance were it not for the current investigation, we further assessed how many additional non-ascertained prion disease cases would need to exist for each ascertained prion disease case in order for the observed outcome to not significantly differ from the expected outcome. Student’s T-test was used for the conformational assays.

Results

Genetic analysis

Methionine (M)/valine (V) heterozygosity at codon 129 (129MV) of the prion protein (PrP) gene was observed in cases 1 and 2, and methionine homozygosity (129MM) in case 3. No mutations or other variations in the open reading frame of the PrP gene were found.

Clinical history

Case 1: Eighty-four-year old male with no history of familial diseases nor of alcohol or substance abuse. He served as lieutenant in the US Army, but never saw combat. He played football for 4 years in high school, 4 years in college, and 1 year in the National Football League (NFL), as a defensive back and on special teams. During this period, he apparently sustained countless concussions but he only lost consciousness once and suffered a vertebral fracture. The first CTE-related clinical signs were noted at age 79 with outbursts of anger along with memory, executive function, attention, and language difficulties. He also experienced infrequent but severe headaches. Three years later, motor problems affecting dressing, walking and golf playing were also noted. The following year, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and was prescribed Levodopa. A nuclear medicine DAT scan, however, was normal. Brain MRI demonstrated generalized cerebral atrophy and small vessel white matter ischemic changes. The diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration was considered. He declined very rapidly over the last year of his life, and by the last month, he could not move or speak. He expired at the age 84 after an apparent disease duration of approximately 5 years.

Case 2: Sixty-eight-year old male with no known relevant family or military history and with no history of alcohol or substance abuse. He played football for 4 years in high school, 4 years in college, and 10 years in the NFL, an offensive lineman. At age 64, following an auto accident, he complained of cluster headaches and family members noted forgetfulness. Approximately 1 year later, he developed left sided face burning and impaired speech. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at the time was consistent with transient ischemic attacks. With treatment, his speech improved slightly. At age 66, he showed cognitive decline and difficulty performing work-related activities. This was followed by a rapid decline in cognition, including impaired memory, attention, executive functioning and language. He also demonstrated paranoia, as well as disinhibited and impulsive behavior. Brain MRI demonstrated bilateral symmetric cortical restriction diffusion and FLAIR signal abnormality thought to be consistent with CJD. Electroencephalogram (EEG) was also abnormal but cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was equivocal. At age 67, he received the diagnosis of CJD following examination at a university clinic. However, the diagnosis was considered uncertain given his borderline CSF 14–3-3 protein positivity, relatively prolonged rate of decline and absence of classic myoclonic jerks. Other possible diagnoses included autoimmune disease and paraneoplastic syndrome, but all tests were normal. Nevertheless, he was started on intravenous immunoglobulin treatment with no benefit. The diagnosis of FTLD associated with CTE was considered. In the year prior to his death, the patient developed weakness and gait disturbance. He expired at 68 years of age following an apparent disease duration of 4 years.

Case 3: Forty-eight-year-old male, premature at birth, with no history of military service. The father was affected by an unspecified psychiatric disorder and was abusive. At age 14, 6 months after parents divorced, the patient was involved in an automobile accident, which resulted in the patient’s brother death, reportedly leaving the patient with feelings of guilt. At age 16 he started drinking alcohol heavily and smoking marijuana. By his mid-20s he was an alcoholic, used drugs, and was often involved in fist-fights that left facial bruises. He was involved in at least two major car accidents with evidence of head trauma; one at approximately age 29 and the other at age 47 about 1 1/2 years before death. Despite these injuries, he was able to perform his trade as carpenter. At the age of 48 years, he was noted to be confused and delirious and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and PTSD after examination at a local hospital. Neurological examination showed ophthalmoplegia, ataxia, confusion and rigidity. He was diagnosed with Wernicke encephalopathy and possible neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Thiamine and other treatments were ineffective, and the patient was transferred to a university hospital. MRI revealed asymmetric signal hyperintensity in parietal and occipital cortices, and caudate nucleus. Sharp wave periodic complexes were found on EEG leading to the diagnosis of prion disease. The only laboratory diagnostic tests for prion disease that could be performed was, neuron specific enolase which was elevated. The patient expired at 48 years after an apparent duration of prion disease of 7 weeks.

Histopathological examination

Case 1 (CTE MV1-2C) (Additional file 1: Table S1)

Hematoxylin-eosin (HE): Severe spongiform degeneration (SD) was detected throughout most the cerebral cortex examined except for the hippocampus and insular cortex. SD was characterized by a mixture of fine and large, occasionally confluent vacuoles with severe astrogliosis and little neuronal loss. Large vacuole SD predominated in the temporal neocortex (Fig. 1a). SD with large vacuoles was also prominent in the molecular layer of cerebellum with focal distribution and enhancement in the depth of the sulci (Fig. 1b). SD was minimal in neostriatum, thalamus and dorsal midbrain with good preservation of substantia nigra and locus coeruleus. Eosinophilic rounded structures, possibly corresponding to unstructured Aβ plaques and focal status spongiosus were present in the superficial cortex (Fig. 1a). Multiple small micro infarcts were also present in the motor cortex.

Prion histopathology in CTE Cases 1–3. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) (a, b, f, g, j, k) and PrP immunohistochemistry (c-e, h, i, l, m). a: Severe spongiform degeneration (SD); dashed inset: higher magnification of a core amyloid β (Aβ) plaque; dotted inset: SD with large vacuoles. b: Focal distribution of large vacuoles SD in the molecular layer of the cerebellum; inset: large vacuoles typically affecting the deeper region of the molecular layer. c and d: Widespread “synaptic” PrP immunostaining (c) along with focal coarse and perivacuolar patterns (d); c, inset: enhancement of PrP immunoreactivity around an Aβ plaque. e: Larger and clustered PrP granules co-distributed with small vacuoles SD in the molecular layer; inset: higher magnification in the depth of a sulcus. f: Severe atrophy with gliosis and neuronal loss; arrow: reactive astrocyte. g: Atrophy, gliosis and kuru plaques in the granular cell layer; arrow: reactive astrocyte; arrowhead: kuru plaque. h: Plaques and plaque-like PrP deposits in a background of coarse PrP granules; inset: PrP staining of a kuru plaque. i: Coarse, plaque and plaque-like PrP immunostaining patterns in molecular and granular layers, and deep white matter; inset: cluster of kuru plaques in the granular layer. j: Small vacuoles SD. k: small vacuoles SD; inset: higher magnification. l: “Synaptic” PrP immunostaining. m: Widespread PrP immunostaining with “brush stroke” pattern of PrP deposition (arrow) in molecular layer typical of sCJDMM1; Ab: 3F4. Scale bar in insets: 25 μm (a and c), 20 μm (h) and 50 μm (b, e, i, k)

Immunohistochemistry PrP: The dominant pattern of PrP deposition in the cerebral cortex was punctate. Enhanced PrP immunoreactivity was occasionally observed around the eosinophilic structures seen on HE. (Fig. 1c). Deposits of coarse PrP were found in the temporal cortex (Fig. 1d). The subcortical white matter, neostriatum and brain stem were unstained. Coarse granular deposits and plaque-like formations in a background of fine granular deposits were common in the cerebellum where they were preferentially distributed in the superficial molecular layer, occasionally at the depths of the sulci (Fig. 1e).

P-tau: Perivascular p-tau pathology as neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), thorn-shaped astrocytes and cell processes, the pathognomonic lesion of CTE, was found throughout the motor, temporal and parietal cortices (Fig. 2a). Other neuropathological features of CTE included NFT and neuropil threads in superficial layers (II-III) of the temporal neocortex (Fig. 2b), and the glial tangles in thalamic nuclei. NFT were dense and widespread in the medial temporal lobe, including the amygdala, entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. NFT were also found in the deep nuclei, brainstem and dentate nucleus of the cerebellum.

Tau and PrP immunostaining in CTE Cases 1–3. a: Perivascular tau pathology consisting of p-tau immunoreactive neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), dotlike neurites and immunoreactive astrocytes distributed in an irregular pattern in deep cortical regions. b: NFT preferentially involving the superficial layers (layers II-III); inset: tau-positive dystrophic neurites associated with an Aβ plaque. c-e (p-tau and PrP double immunostaining): Overall, p-tau neurofibrillary pathology (brown in c and e, cyan in d) predominated in the superficial layers of the cerebral cortex while PrP pathology (cyan in c and e, brown in d) preferential affected deeper layers; e: arrow: perivascular p-tau pathology. f: P-tau immunoreactive “dot-like” structures (arrow); arrowhead: neuropil thread. g: Perivascular p- tau pathology with thorn-shaped astrocytes; arrowheads: blood vessels. h: P-tau immunoreactive astrocytes. i and j (p-tau and PrP double immunostaining): p-tau neurofibrillary pathology (brown in i and cyan in j) preferentially affecting the superficial layers of the cerebral cortex while PrP pathology (cyan in i, brown in j) predominated in deep layers; i: arrowhead: perivascular p-tau pathology. k and l: Perivascular p-tau NFT and dot-like neurites in a deep cortical region (k); subpial perivascular thorn-shaped astrocytes and NFT (j); l, inset: a NFT. Abs 3F4 (to PrP) and AT8 (to tau). Scale bar in insets: 25 μm (b) and 20 μm (l)

Aβ: Subpial Aβ deposition as well diffuse and core plaques were present in the cerebral cortex (Additional file 2: Figure S1. a). Mild meningeal amyloid angiopathy was found in the occipital lobe. Small to medium size punctate Aβ deposits were present in the hippocampus and caudate; the cerebellum was unremarkable. Staining with Thioflavin S was negative. The “ABC” score (“A” = phase for Aβ plaques; “B” = Braak stage for NFT and “C” = CERAD neuritic plaque score), a score of the level of Alzheimer’s disease-related neuropathology features, was A2, B2, C0 corresponding to “intermediate” level of AD neuropathological change (ADNC) [33].

TDP-43 immunostaining disclosed cytoplasm inclusions and neurites in the frontal cortex, medial temporal lobe and brainstem (Additional file 2: Figure S1 b).

Alpha-synuclein immunostaining demonstrated occasional Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites in the olfactory bulbs.

In summary, the histopathological phenotype of the prion disease in this case resembled that of sCJDMV1-2C in the cerebrum and cerebellum. P-tau pathology was diagnostic for CTE, Stage IV and co-existed with diffuse and core Aβ plaques, (without neuritic plaques), consistent with intermediate ADNC, widespread TDP-43 pathology, and alpha-synuclein deposition in the olfactory bulbs.

Case 2 (CTE MV2K-C)

HE: The cerebral cortex showed widespread, severe atrophy, with prominent astrogliosis and neuronal loss. SD was scattered and comprised of medium and occasional large vacuoles; status spongiosus was present near the surface (Fig. 1f). SD was severe in neostriatum and cerebellar molecular layer (Fig. 1g). The granule cell layer of the cerebellum was atrophic and showed kuru plaques, which, to a lesser extent, were also seen in the molecular layer. The brainstem exhibited gliosis in the dorsal midbrain and SD with pigment loss in the substantia nigra.

Immunohistochemistry PrP: Immunostaining was intense in most of the brain regions; in the cerebral cortex, it was characterized by coarse and fine granular staining, mature plaques and plaque-like formations (Fig. 1h). Plaque-like formations were also seen in the neostriatum. The subcortical white matter showed a similar staining pattern suggestive of degenerating axons and glial cells (Additional file 2: Figure S1 c and d). The staining patterns in the cerebellum included kuru plaques, plaque-like and coarse granules in the molecular layer; plaques were also present in the white matter along with scattered structures probably representing degenerating axons (Fig. 1i). The dentate nucleus, substantia nigra, locus coeruleus and inferior olive were all positive.

P-Tau: NFT and thorn-shaped astrocytes populated primarily the superficial frontal, parietal and temporal cortices forming occasional perivascular clusters of NFT and glial tangles at the depths of the sulci (Fig. 2f-h), while they were present in lower density the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex and amygdala (Fig. 2c-e).

Aβ: There were granular Aβ deposits in the cortex and corpus striatum and rare Aβ core-plaques (Additional file 2: Figure S1 e). Staining with Thioflavin S was negative. The “ABC” score was A2, B1, C0 corresponding to “low” level ADNC.

TDP-43: Rare TDP-43 neurites were found in the frontal cortex and medial temporal lobe structures.

Alpha-synuclein immunostaining: negative.

In summary, the histopathological phenotype mimicked that of sCJDMV2K-C with prominent axonal degeneration in white matter. The p-tau pathology was diagnostic for CTE, Stage II while the Aβ immunostaining was of low severity and consistent with aging.

Case 3 (CTE MM1)

HE: The cerebral cortex showed fine SD and astrogliosis that were most severe in occipital than in parietal, frontal and temporal cortices (Fig. 1j). SD was also severe in the cerebellar molecular layer, moderate to minimal in neostriatum and thalamus, and absent in brainstem (Fig. 1k). The locus coeruleus and substantia nigra were well preserved. No plaques were detected.

Immunohistochemistry PrP: Intense punctate or “synaptic” staining was uniformly distributed throughout the cerebral cortex, with occasional collections of coarser granules that rarely formed noticeable aggregates (Fig. 1l). A conspicuous single plaque-like formation was present in the entorhinal region. Selective staining around the perikaryon and dendrites of neurons was seen in deep cortical regions especially the entorhinal and occipital cortices. Widespread granular staining was seen in neostriatum and brainstem but not in the locus coeruleus and substantia nigra. The cerebellum showed a “brush stroke” PrP deposition in a background of diffuse staining in molecular layer characteristic of sCJDMM (MV)1 (Fig. 1m). No immunostaining was seen in the white matter.

P-tau: Focal perivascular NFT, dot-like neurites and immunoreactive glial cells were found around small vessels at the depths of the sulci in the frontal, parietal and temporal cortices (Fig. 2i-l). No p-tau pathology was present in the medial temporal lobe structures. Pre-tangles and p-tau immunoreactive granular astrocytes were present in the thalamus and dorsal brain stem. There was no apparent regional or cellular co-localization between p-tau and PrPD pathology.

Aβ: Diffuse plaques were scattered within the neocortex (Additional file 2: Figure S1 f). Staining with Thioflavin S was negative. The “ABC” score was A1, B1, C0 corresponding to “low” level ADNC.

TDP-43: Negative.

Alpha-synuclein: Negative.

In summary, this case showed the histopathological prion phenotype of severe sCJDMM1 associated with CTE Stage II and Aβ diffuse plaques.

Other CTE cases: Fifty-three additional cases were examined and found negative for PrP immunostaining.

Lesion profile

The lesion profiles reflecting the brain distributions and severity of SD and astrogliosis in each of the three CTE prion positive cases matched the corresponding profile of the respective controls (Fig. 3).

Lesion profiles of CTE, and matched sCJD controls. The lesion profiles from each of the prion-positive CTE cases matched that of the respective sCJD control. a: CTE MV1-2C (case 1) and sCJDMV1-2C. The hippocampus from the CTE case was unavailable for lesion rating. b: CTE MV2K-C (case 2) and sCJDMV2K-C. c: CTE MM1 (case 3) and sCJDMM1. Lesion profiles were generated using the combined scores (mean ± SEM) for spongiform degeneration (SD) and gliosis for each of the 10 brain regions examined. SD was scored on a 0 to 4 scale (0, not detectable; 1, mild; 2, moderate; 3, severe). Gliosis was scored on a 0 to 4 scale (0, not detectable; 1, scattered activated nuclei; 2, moderate activated nuclei; 3, some reactive astrocytes with visible perikaryon; 4, mostly reactive astrocytes with visible perikaryon). FC: frontal cortex (cx); TC: temporal cx; PC: parietal cx; OC: occipital cx; HI: hippocampus (CA1 region); EC: entorhinal cx; BG: basal ganglia; TH: thalamus, SN: substantia nigra; CE: cerebellum

Detection and typing of resPrPD

Immunoblot analysis of PK-digested BH demonstrated the presence of disease-related PK-resistant PrP (resPrPD) in all three cases examined. Overall, the electrophoretic profiles of the three CTE cases closely resembled those of the respective controls subsets (Fig. 4). Taking advantage of four Abs, 3F4 to both resPrPD types, 12B2 and 1E4 preferentially to type 1 and 2, respectively, and SAF70 to the proximal C-terminal region, we obtained the following data for each of the three CTE cases. Case 1, CTE MV1-2C, showed the presence of type 1 in all regions except for the temporal cortex where only type 2 was present; in the frontal and entorhinal cortices types 1 and 2 co-existed in seemingly similar amounts (Fig. 4a and d) while minimal amounts of type 2 were found in all remaining regions (data not shown). Small amounts of the additional fragments 18.5 kDa, 17 kDa and CTF 13 kDa were also seen (Fig. 4a and d, and data not shown) [38, 63]. In case 2, CTE MV2K-C, resPrPD type 2 (19 kDa) was invariably present in all of the regions and it was associated with a minor 20 kDa unglycosylated fragment often referred to as “intermediate” (i) [36, 37, 41, 48] in the cerebrum but not in cerebellum. (Fig. 4b and d). An additional fragment of approximately 18 kDa was detected in the cerebellum with all Abs but 12B2 [42]. No additional fragments were detected with SAF70 (Fig. 4b and d). Case 3, CTE MM1, was straightforward featuring similar amounts of resPrPD type 1 in all ten brain regions (data not shown). The two fragments, 18.5 kDa and CTF 13 kDa, commonly associated with sCJDMM1, were detected in all regions but thalamus (Fig. 4c and d, and data not shown).

Immunoblot study of PrPD brain regional characteristics. a-c: Immunoblots were carried out with proteinase K (PK)-treated brain homogenates (BH) obtained from the indicated brain regions sampled from the three study cases (CTE MV1-2C, CTE MV2K-C and CTE MM1) and sCJD controls (MV1, MV2C, MV2K and MM1). Different sample volume loads or exposures were used, to obtain a comparable representation of PK-resistant PrPD (resPrPD) bands. Membranes were probed with the indicated Abs to PrP: 3F4 to both resPrPD 1 and 2, 12B2 and 1E4 preferentially to type 1 and 2, respectively; SAF70 to the proximal C-terminal region. d: resPrPD loaded at higher concentrations (~ 1 mg tissue equivalent) in all lanes and were probed with SAF70. a and d: In CTE MV1-2C case 1, Ab 3F4 revealed resPrPD type 1 in all brain regions either as the sole component or associated with a higher mobility band in frontal (FC) and entorhinal cortices (EC) consistent with resPrPD type 2; resPrPD type 2 only was observed in the temporal cortex (TC). This type distribution was confirmed by probing with Ab 12B2 (to PrPD type 1) and by Ab 1E4 (preferentially to type 2). Ab SAF70, showed two fragments of 18.5 and 17 kDa commonly associated with resPrPD types 1 and 2, respectively, (solid arrowhead) and the C-terminal fragment CTF 13 kDa (asterisk). These fragments were visible, in the study case and controls BH at higher BH concentration (d). b and d: In CTE MV2K-C case 2, 3F4 showed the presence of a doublet of 19 kDa (dotted arrow) and 20 kDa (solid arrow) in all regions as typically seen in sCJDMV2K, with the exception of the cerebellum, which presented the 19 kDa band together with a fragment of about 18 kDa. Abs 12B2 and 1E4 detected the 20 kDa and 19 kDa component of the doublet, respectively. In putamen the 20 kDa fragment was detected only at the longer exposure (data not shown). SAF70 did not detect any additional fragments in the study case and sCJDMV2K control. c and d: In CTE case 3 MM1, 3F4 showed the presence of PrPD type 1 (21 kDa) in all different brain regions, which was confirmed with 12B2 while 1E4 showed no type 2 (blue arrow: non-specific band); SAF70 demonstrated the 18.5 kDa and CTF-13 fragments, typically present in sCJDMM1(MV)1. PC: parietal cortex (cx); OC: occipital cx; HI: hippocampus; CN: caudate nucleus; PUT: putamen; TH: thalamus; CE: cerebellum

PrPD conformational tests: Conformational stability and solubility assay (CSSA) and conformational stability immunoassay (CSI)

CSSA was performed assessing denaturation rate at increasing concentration of GdnHCl of total PrPD (totPrPD) (comprising PK-sensitive PrPD and resPrPD isoforms) and resPrPD extracted from the three study cases and their controls. The amounts of GdnHCl needed to solubilize half of totPrPD and of resPrPD (GdnHCl1/2 values) of cases 1–3 were similar to those of their controls (Fig. 5a-d). In contrast, and according to published results, GdnHCl1/2 values significantly diverged when CSSA was performed on PrPD preparations from sCJDMM1 and sCJDMM2 which harbor the distinct PrPD strains types 1 and 2 (Fig. 5a-d).

Conformational stability and solubility assay (CSSA) of PrPD species. Solubility and stability of totPrPD (PK-) and resPrPD (PK+) were measured as [GdnHCl]½ molar values, which denotes the molar concentration competent to solubilize half of the substrate. a and b: No significant difference related to totPrPD and resPrPD was detected between each of the CTE cases 1–3 and their respective controls (n = 3). By contrast, both totPrPD and resPrPD values were significantly different in sCJDMM1 and sCJDMM2 as expected. Mean [GdnHCl]½ molar values for totPrPD and resPrPD were: in CTE case 1, 1.44 and 1.8, respectively, and 1.58 ± 0.11 and 1.95 ± 0.13 in controls; in case 2, 1.49 and 1.68, with 1.5 ± 0.04 and 1.69 ± 0.14 in controls; in case 3, 1.78 and 1.93, with 1.43 ± 0.08 and 1.84 ± 0.02 in controls. Mean totPrPD and resPrPD values were 1.43 ± 0.08 and 1.84 ± 0.02 and 1.02 ± 0.06 and 1.22 ± 0.06 in sCJDMM1 and sCJDMM2 respectively. * p ≤ 0.05, *** p ≤ 0.001. c and d: Representative immunoblots of total and resPrPD of CTE cases 1–3 and controls probed with Ab 3F4 at increasing concentrations of GdnHCl

In CSI, GdnHCl required to rendering resPrPD PK-sensitive was used as a measure of relative conformational stability [43, 44, 50]. CSI also failed to detect a difference in resPrPD stability between the three CTE cases and controls while it significantly distinguished sCJDMM1 and sCJDMM2 subtypes (Fig. 6a-b).

Conformational stability immunoassay of resPrPD. a: No significant difference was detected between each of the CTE cases 1–3 and their controls (n = 3) in PK-resistance following exposure to GdnHCl. As expected, stability of resPrPD associated with sCJDMM1 and sCJDMM2 were both significantly different. Mean [GdnHCl]½ molar values in CTE case 1–3 and controls were: 1.77 and 1.98 ± 0.08 respectively; 1.61 and 1.62 ± 0.09; and 2.01 and 1.95 ± 0.05 respectively. In sCJDMM1 and sCJDMM2 mean [GdnHCl]½ molar values were 1.95 ± 0.05 and 1.39 ± 0.17, respectively. * p ≤ 0.05. b: Immunoblots probed with 3F4 at increasing GdnHCl concentrations

Prion disease incidence in CTE: Statistical analysis

The 55 CTE subjects contributed a total of 3630 person-years (mean = 66). The expected number of prion disease cases in this cohort by chance alone was 0.0042. The probability of two or more cases in this cohort occurring by chance alone was 8.93*10− 6. One or both of these cases may have been undetected or not ascertained in national surveillance except for this investigation; however, the observed number of two prion disease cases would still be significantly different from expected (p < 0.05) if the true incidence of prion disease (both ascertained and not ascertained) was up to 83 times the number of ascertained cases.

Discussion

We found prion disease in three subjects with neuropathologically confirmed CTE, including two subjects from a cohort of 55 CTE cases and in one subject clinically diagnosed with PTSD and probable prion disease who was found serendipitously. In all three cases, the CTE was characterized by accumulations of p-tau in neurons and astrocytes around small vessels preferentially at the depths of the cortical sulci. Two cases (ages 64 and 48 years at time of death) were diagnosed with CTE, Stage II, and the third (Case 1, age 84 years) was diagnosed with CTE, Stage IV. All three cases were associated with variable degrees of co-morbid Aβ pathology. Widespread TDP-43 deposits were found in cases 1 and 2, and alpha-synuclein deposits in the olfactory bulb of case 1.

Relatively few detailed neuropathological examinations of individuals clinically diagnosed with PTSD have been reported in the literature, primarily in military personnel exposed to blast and concussive injury [39, 52]. Of the 10 cases in the literature, seven were reported to have p-tau pathology of various severity and six were diagnosed with CTE; three cases featured only prominent astrogliosis consistent with posttraumatic scarring. The seven reported PTSD cases harboring p-tau pathology bear strong resemblance to our cases 2 and 3 with CTE Stage II. Our case 1 was diagnosed with CTE, Stage IV but was much older at the time of death compared to the other reported cases (range 22–48, mean = 37 years). All these cases underline the close correlation between PTSD and CTE [39, 52].

We evaluated the type, severity and distribution of the prion histopathology along with characteristics and conformational properties of the resPrPD. These features, which provide a rough assessment of the PrPD strain, did not significantly differ from corresponding features of matching sCJD subtypes used as positive controls (Additional file 1: Table S1). Specifically, prion-positive CTE case 3, which harbored the genotype MM at codon 129 of the PrP gene coupled with resPrPD type 1 (CTE CJDMM1), showed the same phenotypic and PrPD characteristics as the sCJDMM1 subtype. Similarly, CTE cases 1 and 2, both of whom had the MV 129 genotype, coupled with resPrPD comprising both types 1 and 2 in case 1 (CTE CJDMV1-2C), and with PrPD type i-2 variant in case 2 (CTE-CJDMV2K-C), matched phenotypic and PrPD features of typical sCJDMV1-2C and sCJDMV2K-C (or sCJDMVi-2C), respectively.

Clinically, in case 3, the prion disease presented as rapidly progressive mental deterioration with motor signs as well as positive laboratory tests and MRI. CJD was suspected at disease midcourse in case 2. These clinical data combined with the severity of the prion disease pathology in all 3 cases suggest that the prion disease was superimposed on pre-existent CTE. Taken together, our findings suggest that the prion disease phenotype in CTE was not demonstrably impacted by the coexistence of CTE or the remote occurrence of neurotrauma. If prion disease were an intrinsic component of CTE, one would expect that a divergent histopathological phenotype or PrPD characteristics [14, 34, 46, 53].

The frequent participation of two or more proteinopathies in a neurodegenerative disease is well-established and increasingly common with advanced age at death [3, 19, 27, 53, 54]. Prion proteinopathy appears to be no exception. Sporadic CJD has been reported to co-occur with AD [58, 59] and in association with the pathology of multiple system atrophy [49]. A possible pathogenic mechanism to explain multiprotein degeneration is cross-seeding, in which aggregates of misfolded proteins acting as a seed to induce the formation of misfolded aggregates of heterologous proteins [35, 60]. Experimental data have provided the proof-of-concept for cross-seeding but most of the evidence comes from in vitro experiments [35]. Cross-seeding does not exclude other mechanisms that would explain the co-occurrence of multiple pathological proteins in CTE and other neurodegenerative conditions [60] including a failure of the proteostasis network, a multisystem apparatus dedicated to assist protein folding and prevent protein aggregation. Proteostasis failure, may result from aging or local conditions as trauma and tissue stress [10, 24, 26]. Furthermore, there is accumulating evidence that the deposition of one abnormal protein creates the conditions for, or facilitates, the aggregation of other vulnerable proteins in a “cascade” sequence [19, 53, 54].

The occurrence of sCJD in 2 cases of a CTE cohort comprising 55 subjects would be statistically consistent with a sporadic prion disease incidence of over 100 cases per million people per year. This incidence is at least 83 times higher than the currently reported US incidence (Maddox RA et al., 2018, unpublished results), or a similar magnitude higher than that reported for other countries [9]. Only a rigorous population study involving many more CTE cases will conclusively establish whether the risk of CJD (or of particular subtypes thereof) is increased in patients with CTE.

Conclusions

We report for the first time the occurrence of CJD in three cases with CTE. Our results indicate that the CJD phenotype and resPrPD characteristics, including conformation, in these three cases with sCJD-CTE co-occurrence show no difference from corresponding cases with sCJD occurring alone; they also provide preliminary evidence that CTE increases the risk of sCJD.

Abbreviations

- Abs:

-

antibodies

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ALS:

-

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Aβ:

-

amyloid beta

- BH:

-

brain homogenate

- CENC:

-

Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium

- CJD:

-

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease

- CSI:

-

conformational stability immunoassay

- CSSA:

-

conformational stability and solubility assay

- CTE:

-

chronic traumatic encephalopathy

- FTLD:

-

frontotemporal lobar degeneration

- GdnHCl:

-

guanidine HCl

- HE:

-

hematoxylin-eosin

- M:

-

methionine

- NFT:

-

neurofibrillary tangles

- NPDPSC:

-

National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center

- PK:

-

proteinase K

- PrP:

-

prion protein

- PrPD :

-

abnormal disease-related PrP

- P-tau:

-

hyperphosphorylated tau protein

- PTSD:

-

posttraumatic stress disorder

- sCJD:

-

sporadic CJD

- SD:

-

spongiform degeneration

- TBI:

-

traumatic brain injury

- TDP-43:

-

TAR DNA binding protein 43

- V:

-

valine

- VA-BU-CLF:

-

Veterans Affairs-Boston University-Concussion Legacy Foundation

- WB:

-

Western blot

- α-syn:

-

α synuclein

References

Adams JW, Alvarez VE, Mez J, Huber BR, Tripodis Y, Xia W, Meng G, Kubilus CA, Cormier K, Kiernan PT et al (2018) Lewy body pathology and chronic traumatic encephalopathy associated with contact sports. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 77:757–768. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnen/nly065

Barnes DE, Byers AL, Gardner RC, Seal KH, Boscardin WJ, Yaffe K (2018) Association of Mild Traumatic Brain Injury with and without Loss of consciousness with dementia in US military veterans. JAMA Neurol 75:1055–1061. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0815

Boller F, Mizutani T, Roessmann U, Gambetti P (1980) Parkinson disease, dementia, and Alzheimer disease: clinicopathological correlations. Ann Neurol 7:329–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410070408

Cali I, Castellani R, Alshekhlee A, Cohen Y, Blevins J, Yuan J, Langeveld JP, Parchi P, Safar JG, Zou WQ et al (2009) Co-existence of scrapie prion protein types 1 and 2 in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: its effect on the phenotype and prion-type characteristics. Brain 132:2643–2658. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp196

Cali I, Castellani R, Yuan J, Al-Shekhlee A, Cohen ML, Xiao X, Moleres FJ, Parchi P, Zou WQ, Gambetti P (2006) Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease revisited. Brain 129:2266–2277. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl224

Cali I, Cohen ML, Hasmall yi US, Parchi P, Giaccone G, Collins SJ, Kofskey D, Wang H, McLean CA, Brandel JP et al (2018) Iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with amyloid-beta pathology: an international study. Acta Neuropathol Commun 6:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-017-0503-z

Cannon A, Bieniek KF, Lin WL, Notari S, Zou WQ, Gambetti P, Pedraza O, Graff-Radford NR, Ferman TJ, Dickson DW (2014) Concurrent variably protease-sensitive prionopathy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol 128:313–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-014-1309-8

Cescatti M, Saverioni D, Capellari S, Tagliavini F, Kitamoto T, Ironside J, Giese A, Parchi P (2016) Analysis of conformational stability of abnormal prion protein aggregates across the Spectrum of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease prions. J Virol 90:6244–6254. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00144-16

Chen C, Dong XP (2016) Epidemiological characteristics of human prion diseases. Infect Dis Poverty 5:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-016-0143-8

Chiti F, Dobson CM (2017) Protein Misfolding, amyloid formation, and human disease: a summary of Progress over the last decade. Annu Rev Biochem 86:27–68. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045115

Collins SJ, Sanchez-Juan P, Masters CL, Klug GM, van Duijn C, Poleggi A, Pocchiari M, Almonti S, Cuadrado-Corrales N, de Pedro-Cuesta J et al (2006) Determinants of diagnostic investigation sensitivities across the clinical spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain 129:2278–2287. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl159

Cracco L, Notari S, Cali I, Sy MS, Chen SG, Cohen ML, Ghetti B, Appleby BS, Zou WQ, Caughey B et al (2017) Novel strain properties distinguishing sporadic prion diseases sharing prion protein genotype and prion type. Sci Rep 7:38280. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38280

Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Dams-O’connor K, Trittschuh E, Leverenz JB, Keene CD, Sonnen J, Montine TJ, Bennett DA, Leurgans S et al (2016) Association of Traumatic Brain Injury With Late-Life Neurodegenerative Conditions and Neuropathologic Findings. JAMA Neurol 73:1062–1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1948

Gambetti P, Cali I, Notari S, Kong Q, Zou WQ, Surewicz WK (2011) Molecular biology and pathology of prion strains in sporadic human prion diseases. Acta Neuropathol 121:79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-010-0761-3

Gambetti P, Kong Q, Zou W, Parchi P, Chen SG (2003) Sporadic and familial CJD: classification and characterisation. Br Med Bull 66:213–239

Ghoshal N, Cali I, Perrin RJ, Josephson SA, Sun N, Gambetti P, Morris JC (2009) Codistribution of amyloid beta plaques and spongiform degeneration in familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with the E200K-129M haplotype. Arch Neurol 66:1240–1246. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.224

Goldfarb LG, Petersen RB, Tabaton M, Brown P, LeBlanc AC, Montagna P, Cortelli P, Julien J, Vital C, Pendelbury WW et al (1992) Fatal familial insomnia and familial Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: disease phenotype determined by a DNA polymorphism. Science 258:806–808

Goldstein LE, Fisher AM, Tagge CA, Zhang XL, Velisek L, Sullivan JA, Upreti C, Kracht JM, Ericsson M, Wojnarowicz MW et al (2012) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model. Sci Transl Med 4:134ra160. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3003716

Hardy J, Selkoe DJ (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297:353–356. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072994

Jellinger KA (2004) Head injury and dementia. Curr Opin Neurol 17:719–723

Kascsak RJ, Rubenstein R, Merz PA, Tonna-DeMasi M, Fersko R, Carp RI, Wisniewski HM, Diringer H (1987) Mouse polyclonal and monoclonal antibody to scrapie-associated fibril proteins. J Virol 61:3688–3693

Kim JI, Cali I, Surewicz K, Kong Q, Raymond GJ, Atarashi R, Race B, Qing L, Gambetti P, Caughey B et al (2010) Mammalian prions generated from bacterially expressed prion protein in the absence of any mammalian cofactors. J Biol Chem 285:14083–14087. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.C110.113464

Kobayashi A, Iwasaki Y, Otsuka H, Yamada M, Yoshida M, Matsuura Y, Mohri S, Kitamoto T (2013) Deciphering the pathogenesis of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease with codon 129 M/V and type 2 abnormal prion protein. Acta Neuropathol Commun 1:74. https://doi.org/10.1186/2051-5960-1-74

Labbadia J, Morimoto RI (2015) The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annu Rev Biochem 84:435–464. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-033955

Langeveld JP, Jacobs JG, Erkens JH, Bossers A, van Zijderveld FG, van Keulen LJ (2006) Rapid and discriminatory diagnosis of scrapie and BSE in retro-pharyngeal lymph nodes of sheep. BMC Vet Res 2:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-6148-2-19

Lucke-Wold BP, Turner RC, Logsdon AF, Nguyen L, Bailes JE, Lee JM, Robson MJ, Omalu BI, Huber JD, Rosen CL (2016) Endoplasmic reticulum stress implicated in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neurosurg 124:687–702. https://doi.org/10.3171/2015.3.jns141802

McKee AC, Daneshvar DH (2015) The neuropathology of traumatic brain injury. Handb Clin Neurol 127:45–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52892-6.00004-0

McKee AC, Gavett BE, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Cantu RC, Kowall NW, Perl DP, Hedley-Whyte ET, Price B, Sullivan C et al (2010) TDP-43 proteinopathy and motor neuron disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 69:918–929. https://doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181ee7d85

McKee AC, Robinson ME (2014) Military-related traumatic brain injury and neurodegeneration. Alzheimers Dement 10:S242–S253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.003

McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Daneshvar DH, Lee HS, Wojtowicz SM, Hall G, Baugh CM et al (2013) The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 136:43–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws307

Mez J, Daneshvar DH, Kiernan PT, Abdolmohammadi B, Alvarez VE, Huber BR, Alosco ML, Solomon TM, Nowinski CJ, McHale L et al (2017) Clinicopathological Evaluation of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Players of American Football. JAMA 318:360–370. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.8334

Montenigro PH, Baugh CM, Daneshvar DH, Mez J, Budson AE, Au R, Katz DI, Cantu RC, Stern RA (2014) Clinical subtypes of chronic traumatic encephalopathy: literature review and proposed research diagnostic criteria for traumatic encephalopathy syndrome. Alzheimers Res Ther 6:68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-014-0068-z

Montine TJ, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Dickson DW, Duyckaerts C, Frosch MP, Masliah E, Mirra SS et al (2012) National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: a practical approach. Acta Neuropathol 123:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3

Moreno JA, Telling GC (2017) Insights into mechanisms of transmission and pathogenesis from transgenic mouse models of prion diseases. Methods Mol Biol 1658:219–252. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-7244-9_16

Moreno-Gonzalez I, Edwards Iii G, Salvadores N, Shahnawaz M, Diaz-Espinoza R, Soto C (2017) Molecular interaction between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease through cross-seeding of protein misfolding. Mol Psychiatry 22:1327–1334. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.230

Notari S, Capellari S, Giese A, Westner I, Baruzzi A, Ghetti B, Gambetti P, Kretzschmar HA, Parchi P (2004) Effects of different experimental conditions on the PrPSc core generated by protease digestion: implications for strain typing and molecular classification of CJD. J Biol Chem 279:16797–16804. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M313220200

Notari S, Capellari S, Langeveld J, Giese A, Strammiello R, Gambetti P, Kretzschmar HA, Parchi P (2007) A refined method for molecular typing reveals that co-occurrence of PrP (Sc) types in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is not the rule. Lab Investig 87:1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.3700676

Notari S, Strammiello R, Capellari S, Giese A, Cescatti M, Grassi J, Ghetti B, Langeveld JP, Zou WQ, Gambetti P et al (2008) Characterization of truncated forms of abnormal prion protein in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem 283:30557–30565. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M801877200

Omalu B, Hammers JL, Bailes J, Hamilton RL, Kamboh MI, Webster G, Fitzsimmons RP (2011) Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in an Iraqi war veteran with posttraumatic stress disorder who committed suicide. Neurosurg Focus 31:E3. https://doi.org/10.3171/2011.9.focus11178

Parchi P, Castellani R, Capellari S, Ghetti B, Young K, Chen SG, Farlow M, Dickson DW, Sima AA, Trojanowski JQ et al (1996) Molecular basis of phenotypic variability in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol 39:767–778. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410390613

Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, Brown P, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Windl O, Zerr I, Budka H, Kopp N, Piccardo P et al (1999) Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol 46:224–233

Parchi P, Strammiello R, Notari S, Giese A, Langeveld JP, Ladogana A, Zerr I, Roncaroli F, Cras P, Ghetti B et al (2009) Incidence and spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease variants with mixed phenotype and co-occurrence of PrPSc types: an updated classification. Acta Neuropathol 118:659–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-009-0585-1

Pastore M, Chin SS, Bell KL, Dong Z, Yang Q, Yang L, Yuan J, Chen SG, Gambetti P, Zou WQ (2005) Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) with a mutation at codon 148 of prion protein gene: relationship with sporadic CJD. Am J Pathol 167:1729–1738. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9440(10)61254-0

Peretz D, Scott MR, Groth D, Williamson RA, Burton DR, Cohen FE, Prusiner SB (2001) Strain-specified relative conformational stability of the scrapie prion protein. Protein Sci 10:854–863. https://doi.org/10.1110/ps.39201

Pirisinu L, Di Bari M, Marcon S, Vaccari G, D'Agostino C, Fazzi P, Esposito E, Galeno R, Langeveld J, Agrimi U et al (2010) A new method for the characterization of strain-specific conformational stability of protease-sensitive and protease-resistant PrPSc. PLoS One 5:e12723. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012723

Poggiolini I, Saverioni D, Parchi P (2013) Prion protein misfolding, strains, and neurotoxicity: an update from studies on mammalian prions. Int J Cell Biol 2013:910314. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/910314

Puoti G, Bizzi A, Forloni G, Safar JG, Tagliavini F, Gambetti P (2012) Sporadic human prion diseases: molecular insights and diagnosis. Lancet Neurol 11:618–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70063-7

Ritchie DL, Barria MA, Peden AH, Yull HM, Kirkpatrick J, Adlard P, Ironside JW, Head MW (2017) UK iatrogenic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: investigating human prion transmission across genotypic barriers using human tissue-based and molecular approaches. Acta Neuropathol 133:579–595. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1638-x

Rodriguez-Diehl R, Rey MJ, Gironell A, Martinez-Saez E, Ferrer I, Sanchez-Valle R, Jague J, Nos C, Gelpi E (2012) “Preclinical” MSA in definite Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neuropathology 32:158–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1789.2011.01232.x

Safar J, Prusiner SB (1998) Molecular studies of prion diseases. Prog Brain Res 117:421–434

Safar JG, Xiao X, Kabir ME, Chen S, Kim C, Haldiman T, Cohen Y, Chen W, Cohen ML, Surewicz WK (2015) Structural determinants of phenotypic diversity and replication rate of human prions. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004832. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004832

Shively SB, Horkayne-Szakaly I, Jones RV, Kelly JP, Armstrong RC, Perl DP (2016) Characterisation of interface astroglial scarring in the human brain after blast exposure: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol 15:944–953. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(16)30057-6

Soto C, Pritzkow S (2018) Protein Misfolding, aggregation and conformational strains in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci 21:1332–1340

Spires-Jones TL, Attems J, Thal DR (2017) Interactions of pathological proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol 134:187–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-017-1709-7

Stein TD, Montenigro PH, Alvarez VE, Xia W, Crary JF, Tripodis Y, Daneshvar DH, Mez J, Solomon T, Meng G et al (2015) Beta-amyloid deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol 130:21–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1435-y

Stern RA, Daneshvar DH, Baugh CM, Seichepine DR, Montenigro PH, Riley DO, Fritts NG, Stamm JM, Robbins CA, McHale L et al (2013) Clinical presentation of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Neurology 81:1122–1129. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55f7f

Telling GC, Parchi P, DeArmond SJ, Cortelli P, Montagna P, Gabizon R, Mastrianni J, Lugaresi E, Gambetti P, Prusiner SB (1996) Evidence for the conformation of the pathologic isoform of the prion protein enciphering and propagating prion diversity. Science 274:2079–2082

Tousseyn T, Bajsarowicz K, Sanchez H, Gheyara A, Oehler A, Geschwind M, DeArmond B, DeArmond SJ (2015) Prion disease induces Alzheimer disease-like Neuropathologic changes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 74:873–888. https://doi.org/10.1097/nen.0000000000000228

Tsuchiya K, Yagishita S, Ikeda K, Sano M, Taki K, Hashimoto K, Watabiki S, Mizusawa H (2004) Coexistence of CJD and Alzheimer’s disease: an autopsy case showing typical clinical features of CJD. Neuropathology 24:46–55

Vasconcelos B, Stancu IC, Buist A, Bird M, Wang P, Vanoosthuyse A, Van Kolen K, Verheyen A, Kienlen-Campard P, Octave JN et al (2016) Heterotypic seeding of tau fibrillization by pre-aggregated Abeta provides potent seeds for prion-like seeding and propagation of tau-pathology in vivo. Acta Neuropathol 131:549–569. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1525-x

Weiner MW, Crane PK, Montine TJ, Bennett DA, Veitch DP (2017) Traumatic brain injury may not increase the risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 89:1923–1925. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000004608

Zerr I, Brandel JP, Masullo C, Wientjens D, de Silva R, Zeidler M, Granieri E, Sampaolo S, van Duijn C, Delasnerie-Laupretre N et al (2000) European surveillance on Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a case-control study for medical risk factors. J Clin Epidemiol 53:747–754

Zou WQ, Capellari S, Parchi P, Sy MS, Gambetti P, Chen SG (2003) Identification of novel proteinase K-resistant C-terminal fragments of PrP in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Biol Chem 278:40429–40436. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M308550200

Zou WQ, Zheng J, Gray DM, Gambetti P, Chen SG (2004) Antibody to DNA detects scrapie but not normal prion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:1380–1385. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0307825100

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patient families, referring clinicians, The CJD Foundation, the NPDPSC technical and administrative personnel, in particular Yvonne Cohen, Miriam Warren, Katie Eppich and Janis Blevins for their invaluable assistance.

Funding

The study was supported by NIH P01AI106705, NIH 5R01NS083687 and Charles S. Britton Fund to PG, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grants U01 NS086659, R01 NS078337, R56 NS078337, U01 NS093334, F32 NS096803), the National Institute on Aging (grants K23 AG046377, P30AG13846; supplement 0572063345–5, R01 AG1649, AG057902), the U.S. Department of Defense (grant W81XWH-13-2-0064), Chronic Effects of Neurotrauma Consortium (CENC) Award W81XWH-13-2-0095 and Department of Veterans Affairs CENC Award I01 CX001135, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (I01 CX001038), the Veterans Affairs Biorepository (CSP 501), the Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Traumatic Brain Injury Center of Excellence (grant B6796-C), the Department of Defense Peer Reviewed Alzheimer’s Research Program (DoD-PRARP grant 13267017), the National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment, the Alzheimer’s Association (grants NIRG-15-362697, NIRG-305779), the Concussion Legacy Foundation, Nick and Lynn Buoniconti Foundation, the Andlinger Family Foundation, WWE, and the National Football League to AMK.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC and should not be construed as an official Veterans Affairs or Department of Defense position, policy or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SKN, SN, IC and PG were responsible for the concept and design of the study. SKN, SN, IC, VA, DK, MC, RAS, BA JA, LS, AM and PG were responsible for data analysis and acquisition. SKN, SN, IC and PG were responsible for drafting of figures and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The human tissues used in the current study were provided by VA-BU-CLF brain bank and NPDPSC. All the procedures used in the current study were approved with institutional review board of University Hospitals case medical center (# 5–14-09) and performed as per regulations of 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Aβ, TDP-43 and PrP immunoreactivity in CTE Cases 1–3. a: Widespread Aβ deposits in the subpial surface (arrow) and core dense Aβ plaques (arrowhead) in the frontal cortex. b: TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions (arrow) and “dot-like” structures (arrowhead) in the hippocampus. c and d: Plaque-like PrP deposits (arrow in c) and intense PrP immunoreactivity in the subcortical white matter of the temporal lobe. e and f: Granular Aβ deposits (e) and diffuse Aβ plaques (f) in the parietal (e) and frontal (f) cortices; e, inset: a rare core dense Aβ plaque. Abs: 4G8 (a, e, f), TDP-43 in (b), 3F4 (c and d). Scalebar inset in e: 20 μm. (PDF 3628 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nemani, S.K., Notari, S., Cali, I. et al. Co-occurrence of chronic traumatic encephalopathy and prion disease. acta neuropathol commun 6, 140 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0643-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0643-9