Abstract

Background

Spontaneous salivary otorrhea is a rare presentation only previously documented twice in literature where parotid salivary secretions are found in the external auditory canal. Conventional treatment of spontaneous parotid salivary fistulas includes surgical management with interposed grafts, fistula tract ablation, and possible superficial parotidectomy. Associated risks include facial nerve injury, Frey syndrome and facial scarring. Here we report the first case of spontaneous salivary otorrhea conservatively managed with a type A botulinum toxin (BTA) injection.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old female presented with a 5-month history of left sided otorrhea and transient left facial swelling associated with gustatory stimulation. The otorrhea fluid tested positive for salivary amylase and negative for beta 2 transferrin. Fifty units of BTA were injected into the left parotid gland under ultrasound guidance. Cessation of symptoms was achieved 3 weeks after intervention. The patient remains symptom-free at the 2 year follow up.

Conclusion

BTA injection was well tolerated under ultrasound guidance and has led to long-term resolution of the patient’s symptoms. BTA injection appears to be a safe and effective way to conservatively manage this rare presentation of spontaneous salivary otorrhea.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Salivary otorrhea is a rare condition that has been reported in congenital parotid fistulas, branchial cleft anomalies, and anatomical defects of the external auditory canal. However, to our knowledge, a spontaneous presentation has only been reported twice in literature [1, 2]. Clinical presentation includes production of clear, thin otorrhea in response to gustatory stimuli. Diagnosis has been confirmed with salivary amylase testing of discharge and sialography. Conventional surgical management include fistula tract excision with subsequent placement of temporalis fascia or tragal perichondrium to separate parotid gland from external auditory canal [2]. Depending on the etiology of the lesion, a superficial parotidectomy may be required. Here we present a case of a 17-year-old girl with unilateral spontaneous salivary otorrhea treated with type A botulinum toxin (BTA).

Case presentation

A 17-year-old female was referred to the pediatric otolaryngology outpatient clinic after experiencing acute occipital pain, left sided otorrhea and swelling of the external auditory canal. The otorrhea was noted to continue for several weeks and her symptoms were exacerbated by gustatory stimuli or when undergoing dental procedures. In addition, she developed left facial swelling and intermittent headaches. Her past medical history was significant for Celiac disease and erythema nodosum. At the time of presentation to our clinic, the patient was concurrently being investigated for Behçet disease.

On physical examination, left facial swelling and clear, watery ear discharge was observed. No neck masses or sinus tracts were seen upon inspection. Under a microscopic examination, the tympanic membrane showed no retraction, cholesteatoma, or middle ear effusion. The external auditory canal had a normal contour with no mass or ectopic tissue.

Previous parotid gland scintigraphy with Technetium 99 m uptake, CT Head, CT Temporal bone, and neck ultrasounds performed at other centres revealed no anatomic abnormalities, such as branchial arch remnants or masses. MRI sialography showed normal salivary ducts and no abnormal extravagation of contrast. Beta 2 transferrin testing was negative, ruling out potential cerebral spinal fluid leak. However, the otorrhea tested positive for amylase (> 16,000 units/L) confirming a salivary etiology. A gram stain previously yielded gram-negative rods, gram-negative and positive cocci.

Treatment options were reviewed and the patient elected to proceed with a trial of BTA. Under sterile conditions, the patient’s superficial and deep lobes of the left parotid gland were injected with a total of 50 units of Botox® under ultrasound guidance using a 22-gauge spinal needle. There were no complications.

In post-procedural follow up, the patient reported diminishing otorrhea for 2–3 weeks. Otorrhea ceased after the third week; however, transient intermittent facial swelling continued to be reported with each episode lasting 1–2 h. These episodes gradually subsided and resolved 3 months after injection. Palpation at 3 months yielded minimal salivary secretion from the left Stenson’s duct and no otorrhea. At the 2 year follow up clinic visit, the patient reported no recurrence of any symptoms.

Discussion

Spontaneous salivary otorrhea is a rare condition typically managed with surgical intervention. We report the successful use of BTA as a conservative therapeutic modality for spontaneous salivary otorrhea.

Type A botulinum toxin is a potent neurotoxin created by Clostridium botulinum, widely used for its paralytic effect at the neuromuscular junctions by inhibiting cholinergic signal transduction across the synapse. This is achieved by cleavage of SNAP-25, a component of the soluble n-ethylmaleimide – sensitive factor associated protein receptor (SNARE) complex, on the presynaptic nerves preventing acetylcholine release at the neuromuscular junction, thereby paralyzing the muscle [3]. This property has both cosmetic and therapeutic applications. In the context of salivation, BTA diminishes salivary excretion upon stimulation. This is achieved by BTA toxin disruption of the parasympathetic secretomotor pathway at the cholinergic nerve terminals [4, 5].

BTA injection in the parotid gland for sialorrhea was first cited by Bushara (1997) and has since been widely used in management of sialorrhea [6,7,8,9]. A retrospective study by Send et al., found BTA glandular injections had a 100% treatment success rate in patients with post-operative parotid sialocutaneous fistulas without any recorded adverse events [10]. Longitudinal studies has shown its use to be safe and well-tolerated for long term clinical use [11,12,13].

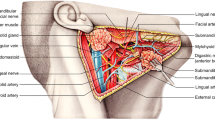

The pathophysiology of the patient’s acute onset of salivary otorrhea is unknown at this point. However, with the clinical presentation and complex past medical history of autoimmune disorders, the cutaneous communication was hypothesized to be formed secondary to an inflammatory process. The diagnosis of salivary otorrhea was challenging due to inability to visualize the fistulous tract despite utilizing an array of diagnostic imaging techniques, including MRI sialography (Fig. 1). A similar encounter was described by Rana et al. where no tracts were visualized with multiple imaging modalities, but upon surgical exploration a soft tissue tract was appreciated [2]. We postulate this tract is only patent with mechanical pressure upon salivation, which would impede spontaneous tissue closure. Thus, utilization of BTA to stop salivary outflow from the parotid gland for 3-month period would allow spontaneous closure of the fistulous tract.

BTA injections into glandular tissue can be performed either under ultrasound guidance, or by palpation by experienced physicians [14]. Injection techniques are less invasive, costly and require less technical skill to perform compared to alternative surgical interventions. With superficial parotidectomies frequently indicated in treatment of salivary aural fistulas, facial nerve complications remain a significant concern. In a systematic review on surgical outcomes of 1317 patients undergoing superficial parotidectomies for benign parotid gland tumors, the incidence of facial nerve paresis and paralysis were 6.75 and 0.8% respectively [15]. In contrast, a longitudinal study on 65 patients receiving at least 3 injections of botulinum toxin A or B for sialorrhea reported no cases of long term facial nerve paralysis or paresis [12]. Nevertheless, mild to moderate transient side effects were noted by some patients in the study, including xerostomia, dysphagia, and viscous saliva [12, 14].

Limitations to BTA injection as the primary treatment is the associated cost. The cost of one unit of Botox® is $5.55 CAD ($277.35 per 50 IU) [16]. The cost of one unit of Xeomin® is $6.12 CAD ($302.00 per 50 IU) [10]. The cost of one unit of Dysport® is $4.69 CAD ($234.50 per 50 IU) [10]. However, cost variations exist depending on country of purchase and quantity of order [16]. Ultimately, cost of treatment will increase incrementally with administered units required per patient. No standardized dosing or treatment guideline has been established. However, an international consensus statement was published by Reddihough et al., in 2010 with recommendations of 10–50 U of BOTOX® per side or 15–75 U of Dysport® per parotid gland for patients with sialorrhea [17]. Case reports have shown neutralizing antibody formation in response to repetitive injections surpassing the lowest effective dose which can cause resistance to the clinical effects of BTA [3]. It must be noted, however, that the potency, clinical efficacy, and duration of effect are not uniform between serotypes, occasionally making dose-response assumptions unpredictable.

Conclusion

We present the third known case of spontaneous unilateral salivary otorrhea, which was successfully treated with a BTA injection. Cessation of otorrhea was achieved three weeks after treatment without recurrence at the 2-year post-procedure time point. More cases are required to assess the efficacy of BTA injections as a definitive treatment, however, BTA appears to be a safe and well-tolerated conservative treatment for patients with salivary otorrhea. This therapeutic modality should be considered as a conservative management option for such conditions.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this study as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study. The report can be substantiated with patient documentation from clinical encounters.

Abbreviations

- BTA:

-

Type A Botulinum Toxin

References

Sharma PD, Dawkins RS. Patent foramen of Huschke and spontaneous salivary fistula. J Laryngol Otol [Internet]. 1984;98(1):83–5. Available from. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6693808.

Rana K, Rathore PK, Raj A, Meher R, Wadhwa V, Prakash A, et al. Bilateral spontaneous salivary otorrhoea: Case report and a review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol [Internet]. 2015 Oct 1 [cited 2018 Feb 4];79(10):1774–7. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi? T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med8&NEWS=N&AN=26260660.

Wheeler A, Smith HS. Botulinum toxins: Mechanisms of action, antinociception and clinical applications [Internet]. Vol. 306, Toxicology. Elsevier; 2013 [cited 2018 Apr 4]. p. 124–46. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300483X13000437?via%3Dihub.

Abboud WA, Nadel S, Hassin-Baer S, Arad A, Dobriyan A, Yahalom R. Ultrasound-Guided Botulinum Toxin Injections into the Salivary Glands for the Treatment of Drooling. Isr Med Assoc J [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 16];21(2):116–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30772963.

Lovato A, Restivo DA, Ottaviano G, Marioni G, Marchese-Ragona R. Botulinum toxin therapy: functional silencing of salivary disorders. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2019 Jun 16];37(2):168–71. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28516981.

Bushara KO. Sialorrhea in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A hypothesis of a new treatment - Botulinum toxin a injections of the parotid glands. Med Hypotheses [Internet]. 1997 1 [cited 2018 Apr 18];48(4):337–9. Available from: https://www-sciencedirect-com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/science/article/pii/S0306987797901031.

Fuster Torres MA, Berini Aytés L, Gay Escoda C. Salivary gland application of botulinum toxin for the treatment of sialorrhea. [Internet]. Vol. 12, Medicina oral, patología oral y cirugía bucal. 2007 [cited 2018 Apr 30]. p. 511–7. Available from: http://www.medicinaoral.com/pubmed/medoralv12_i7_p511.pdf.

Lim M, Mace A, Reza Nouraei SA, Sandhu G. Botulinum toxin in the management of sialorrhoea: A systematic review [Internet]. Vol. 31, Clinical Otolaryngology. 2006 [cited 2018 Apr 18]. p. 267–72. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1749-4486.2006.01263.x.

Von Lindern JJ, Niederhagen B, Appel T, Bergé S, Reich RH. New prospects in the treatment of traumatic and postoperative parotid fistulas with type A botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2018 Jun 12];109(7):2443–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12045574.

Send T, Bertlich M, Eichhorn KW, Bootz F, Jakob M. Management and Follow-up Results of Salivary Fistulas Treated With Botulinum Toxin. Laryngoscope [Internet]. 2019 Feb 1 [cited 2019 May 29];129(2):403–8. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/lary.27416.

D.H. L, T.M. Y, J.K. L, Y.E. J, I.Y. K, W.Y. J, et al. Clinical utility of the inferior turbinate flaps in the reconstruction of the nasal septum and skull base. J Craniofac Surg [Internet]. 2012;23(4):e322–6. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi? T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed13&NEWS=N&AN=365370509.

Petracca M, Guidubaldi A, Ricciardi L, Ialongo T, Del Grande A, Mulas D, et al. Botulinum Toxin A and B in sialorrhea: long-term data and literature overview. [Internet]. Vol. 107, Toxicon : official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. Pergamon; 2015 [cited 2018 Apr 4]. p. 129–40. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0041010115300441?via%3Dihub.

Marchese-Ragona R, De Filippis C, Staffieri A, Restivo DA, Restino DA. Parotid gland fistula: treatment with botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2019 Jul 2];107(3):886–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11314663.

Melville JC, Stackowicz DJ, Jundt JS, Shum JW. Use of Botox (OnabotulinumtoxinA) for the treatment of Parotid Sialocele and fistula after extirpation of Buccal squamous cell carcinoma with immediate reconstruction using microvascular free flap: a report of 3 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg [Internet] 2016;74(8):1678–1686. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2016.01.038.

El Fol HAE, Beheiri MJ, Zaqri WA Al. Comparison of the effect of total conservative parotidectomy versus superficial parotidectomy in management of benign parotid gland tumor: A systematic review. J Cranio-Maxillofacial Surg [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 May 4];2–7. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1010518215000128.

Roze S, Kurth H, Hunt B, Valentine W, Marty R. Evaluation of the cost per patient per injection of botulinum toxin a in upper limb spasticity: Comparison of two preparations in 19 countries [Internet]. Vol. 5, Medical Devices: Evidence and Research. Dove Press; 2012 [cited 2019 Jun 16]. p. 97–101. Available from: http://www.dovepress.com/evaluation-of-the-cost-per-patient-per-injection-of-botulinum-toxin-a%2D%2Dpeer-reviewed-article-MDER.

Reddihough D, Erasmus CE, Johnson H, McKellar GMW, Jongerius PH. Botulinum toxin assessment, intervention and aftercare for paediatric and adult drooling: international consensus statement. Eur J Neurol [Internet]. 2010 15 [cited 2019 Jun 16];17:109–21. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03131.x.

Acknowledgements

Sepideh Mohajeri, MD2 for her invaluable contributions to the review and revision of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have no funding or grants to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TC was responsible for the writing of the manuscript and compilation of provided data. TL was responsible for designing the manuscript and participated in the extensive revision process of the manuscript. DS was responsible for the acquisition of the presented data and was involved in the revision process of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board has exempted this study from the ethics submission. Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report.

Consent for publication

Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of her unique pathology and management. A copy can be provided upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, T.J., Lewis, T.A. & Sommer, D.D. Type a botulinum toxin in the management of spontaneous salivary otorrhea: a case report. J of Otolaryngol - Head & Neck Surg 49, 60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-020-00457-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40463-020-00457-y