Abstract

Background

Medically complex urban patients experiencing homelessness comprise a disproportionate number of high-cost, high-need patients. There are few studies of interventions to improve care for these populations; their social complexity makes them difficult to study and requires clinical and research collaboration. We present a protocol for a trial of the streamlined unified meaningfully managed interdisciplinary team (SUMMIT) team, an ambulatory ICU (A-ICU) intervention to improve utilization and patient experience that uses control populations to address limitations of prior research.

Methods/design

Participants are patients at a Federally Qualified Health Center in Portland, Oregon that serves patients experiencing homelessness or who have substance use disorders. Participants meet at least one of the following criteria: > 1 hospitalization over past 6 months; at least one medical co-morbidity including uncontrolled diabetes, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease, soft-tissue infection; and 1 mental health diagnosis or substance use disorder. We exclude patients if they have < 6 months to live, have cognitive impairment preventing consent, or are non-English speaking. Following consent and baseline assessment, we randomize participants to immediate SUMMIT intervention or wait-list control group. Participants receiving the SUMMIT intervention transfer care to a clinic-based team of physician, complex care nurse, care coordinator, social worker, and pharmacist with reduced panel size and flexible scheduling with emphasis on motivational interviewing, patient goal setting and advanced care planning. Wait-listed participants continue usual care plus engagement with community health worker intervention for 6 months prior to joining SUMMIT. The primary outcome is hospital utilization at 6 months; secondary outcomes include emergency department utilization, patient activation, and patient experience measures. We follow participants for 12 months after intervention initiation.

Discussion

The SUMMIT A-ICU is an intensive primary care intervention for high-utilizers impacted by homelessness. Use of a wait-list control design balances community and staff stakeholder needs, who felt all participants should have access to the intervention, while addressing research needs to include control populations. Design limitations include prolonged follow-up period that increases risk for attrition, and conflict between practice and research; including partner stakeholders and embedded researchers familiar with the population in study planning can mitigate these barriers.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03224858, Registered 7/21/17 retrospectively registered https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03224858

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A small group of high cost-high needs patients (HCHN) accounts for a disproportionate percentage of health care expenditures [1, 2]. These patients often have multiple medical and psychiatric comorbidities and functional impairments [3] that lead to costly and unnecessary care [4], and have increased risk for adverse drug events [5]. The number of specialty physicians involved in their care also increases risk of fragmentation of care [6], and poor transitions of care from hospital to home [7,8,9]. In addition, highly prevalent adverse social factors, such as poverty, homelessness, and substance use disorders increase the risk for overuse of hospital and emergency departments (ED), as well as underuse of primary care [10].

As healthcare systems and Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) assume more financial risk for quality of care delivered to patients, there are efforts to focus and intensify resources for HCHN patients [11]. Innovative intensive primary care (IPC) programs employ a variety of approaches to improve care quality and reduce utilization, including use of multi-disciplinary care teams, increased primary care access, improved coordination and continuity of primary care, and enhanced self-efficacy through counseling or linkages to social services/case management [2, 12]. However, there is unclear evidence for IPC effectiveness. A recent systematic review of IPCs showed mixed effects on utilization [13]. The only study targeting patients with complex social needs examined the VA homeless patient aligned care team (H-PACT) program, an intensive “ambulatory-ICU” (A-ICU) program for homeless Veterans who were unwilling or unable to access traditional primary care [14]. While 6-months pre- and post-enrollment analyses showed a 25% reduction in combined hospitalization and ED utilization, the evaluation lacked a control group. Other gaps in the literature include few interventions targeting HCHN patients in urban community health centers, and those with substance use disorders and co-occurring severe mental illness, independent risk factors for utilization of healthcare services [15,16,17].

There are several reasons for this gap. These patients are difficult to recruit in studies because of their social complexity, and distrust of medical system and may require partnered collaboration between researchers and community-based clinics beyond traditional research methods [18]. Furthermore, these programs occur in real-time in response to stakeholder and patient needs, and evaluation plans are often lower priority than service delivery—there are few learning health systems that have the resources or expertise to conduct evaluation activities in Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) populations [19, 20].

We designed SUMMIT (Streamlined Unified Meaningfully Managed Interdisciplinary Team) to address some of these gaps. We describe a practiced-based research partnership between Old Town Clinic (OTC), an FQHC, and Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), a research institution, in design of a randomized, wait-list control trial to assess whether an A-ICU model of care compared to existing patient centered medical home (PCMH) care improves healthcare utilization, patient experience, and self-efficacy at 6 months for medically and socially complex patients in an urban healthcare for the homeless setting.

Methods/design

Study design and rationale

SUMMIT is a randomized controlled study using a wait-list control design (see Fig. 1), described in prior practice-based research literature [21, 22]. Patients are randomized to start the SUMMIT intervention immediately, or continue with usual primary care for 6 months before crossing over to the SUMMIT intervention with data collection at multiple time-points. Thus, we address limitations of other practiced-based evaluations of IPC interventions that use pre-post designs without control groups. Furthermore, compared to a randomized controlled trial, the wait-list control design is more acceptable to clinic staff, patients, and payer stakeholders who may consider it unethical to deny patients access to the intervention. The wait-list control design permits gradual ramp-up of staffing.

Study setting

We recruit study participants from the OTC, an integrated medical and behavioral healthcare clinic and FQHC in Portland, Oregon. OTC serves over 5000 patients who receive primary care services at the clinic through four PCMH teams. The average age of OTC patients is 48.7 years (± 12.5), and a majority are male (60.9%), White/Non-Latino race/ethnicity (72.2%) with very low incomes (46.5%); about one-third (30%) have at least two chronic medical conditions. Many of OTC patients are referred from housing programs or substance-use treatment programs—67% of OTC patients in 2017 were homeless or unstably housed, and 61% of patients had a substance use disorder diagnosis. In addition to primary care, the clinic provides co-located mental health services delivered by psychiatric nurse practitioners; substance use counseling services and pharmacotherapy for alcohol and opioid use disorders; chronic disease pharmacists and an on-site pharmacy and lab services; wellness and activity classes, including daily acupuncture; integrated occupational and physical therapy, and social work services. Additionally, teams have access to community health workers to assist with patient engagement with primary care. Despite this specialized care, a subset of OTC patients continued to consume provider and staff attention and over utilize hospitals and EDs. A 2014 needs assessment showed 25% of OTC’s patients had at least one hospitalization or six ED visits in the preceding year, and an additional 14% had 2–5 ED visits in the preceding year, spurring development of the SUMMIT intervention.

Starting in 2006, OHSU and OTC initiated a clinical partnership with the goal of working together to identify research opportunities in healthcare disparities, integrated care models and improved access for underserved populations. OHSU-affiliated providers staff OTC clinics, supervise resident continuity clinics, and developed a social medicine curriculum for medical students. More recently, OHSU clinician-researchers embedded at OTC have leveraged the partnership with OTC to design clinical innovations on hospital-based transitions of care, and substance use treatment that utilizes the strengths of each organization [23, 24]. These prior studies were successful in part due to intimate knowledge of the culture of the clinic, patient populations needs, and an awareness of the needs of the partner. Interest in a novel A-ICU care model prompted opportunity to utilize this research collaboration.

Eligibility criteria and recruitment

Box 1 summarizes participant inclusion and exclusion criteria. Primary care providers (PCPs) are encouraged to refer patients whose medical complexity, combined with social and behavioral factors, made it difficult for existing care teams to deliver optimal care. PCPs complete a referral form for patients that meet medical burden criteria (at least one medical condition including congestive heart failure, uncontrolled diabetes, advanced COPD [World Health Organization group C or D], chronic kidney disease (≥ stage 3), end-stage liver disease, chronic or severe soft tissue infections, osteomyelitis, or failure to thrive), utilization criteria (≥ 1 hospitalization or ED visit in the prior 6 months), and substance use disorder defined by referring PCP or chart diagnosis, or behavioral health criteria (≥ 1 psychotic disorder, mood disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]).

The SUMMIT team reviews referrals at regular intervals to confirm clinical appropriateness. Following acceptance to the team, the research assistant (RA) approaches the patient to determine study eligibility, obtain consent and complete the baseline survey. We exclude potential participants if they are non-English speaking, are on hospice at time of enrollment (< 6 months to live), diagnosed with terminal cancer diagnosis, are unable to consent using “teachback” method [25], or are unable to follow-up by phone due to aphasia, and/or severe hearing impairment at time of enrollment.

Participant sample recruitment procedures and timeline

Once consent is obtained, the RA administers the baseline survey that includes demographic, bio-psychosocial assessments and baseline assessment of patient-reported outcomes (Fig. 1). Following completion of the baseline survey, the participant is randomized to immediate entrance into the SUMMIT intervention or placement on a 6-months waitlist. Study participants receive $5 gift cards for each completed survey.

If the participant is randomized to the wait-list control group, they remain in usual care for 6 months. After 6 months, the RA contacts the participant to repeat the study assessments, and the participant transfers care to the SUMMIT team. If the participant is randomized to the intervention group, they are scheduled for an initial intake appointment with the SUMMIT team. The RA contacts participants at 6 and 12 months from date of enrollment for ascertainment of outcomes with a window of 6 weeks defined as 2 weeks prior and 4 weeks after the due date. Participants are followed for 12 months after SUMMIT enrollment (up to 18 months if assignment to wait-list control group).

We sought strategies to improve engagement with participants and minimize loss to follow up, given the complexity of the target population. We asked consented participants to list additional phone numbers and/or addresses as points of contact as part of baseline survey procedures. We convened a patient advisory group, and included in our research meetings a patient liason to introduce the SUMMIT study to obtain feedback from patient advocates regarding study recruitment and follow-up procedures.

Study integrity and randomization

The study design conforms to CONSORT statement recommendations for randomized clinical trials of non-pharmacologic treatment [26]. Upon completion of consent and baseline survey, participants are randomized to either immediate start with the SUMMIT team or be placed on a 6-months wait-list with a 1:1 allocation per computer-generated randomization schedule. We used sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes to attain allocation concealment. A member of the research team not involved in the consent and enrollment process generated the allocation sequence. Following allocation of group assignment, the participant, clinic staff, and RA conducting follow up surveys will not be blinded. The research members conducting the statistical analysis will be blinded from treatment assignment. We will conduct an intent-to-treat analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the OHSU IRB in 2016 (IRB 15285). The study also received a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health to protect data on drug and alcohol use. The protocol is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03224858). None of the investigators have financial or competing interests in conflict with the aims of the trial.

Study arms

Intervention: SUMMIT intervention description

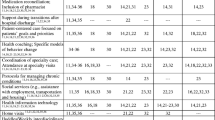

The intervention is a clinic team of co-located multi-disciplinary staff with reduced panel size and flexible scheduling (Box 2). Staffing consists of two half-time physicians (1.0 FTE) with board certification in addiction medicine, one complex care nurse, two care coordinators, two licensed clinical social workers (LCSW), pharmacist, team manager, and quality analyst. All team members have additional training in Motivational Interviewing, patient goal setting, and palliative care principles. These didactic trainings were delivered by partner community organizations during weekly dedicated non-clinical time built into the SUMMIT schedule. The aims of the SUMMIT team are closely aligned with Shippe and Montori’s theory of cumulative complexity, emphasizing ways to increase patient self-efficacy and decrease treatment burden [27]. Core activities (Box 3) include an initial comprehensive intake with medical and behavioral team members, patient driven health goal setting, transitional care protocols when patients experience hospitalizations, medication management assessment, weekly panel review, and case management to address social determinants of health and other unmet needs. The team has flexibility to conduct home visits, facilitate unscheduled clinic visits, accompany patients to specialty appointments, and deliver addictions treatment including medications for addiction treatment. The quality analyst assists the team in developing “Plan-Do-Study-Act” cycles and panel management activities.

Funding SUMMIT

SUMMIT is funded through reallocation of existing staff resources and clinical operations budget, rather than grants. Funding for on-going operations is through a negotiated per-member per-month payment for participants in the care model and fee-for-service payments for patient visits with a regional Medicaid payor.

Wait-list controls: treatment as usual

Usual care operates as a PCMH model (see Fig. 2). Within the clinic, there are four teams consisting of PCP, care team manager (usually a licensed practical nurse), medical assistants, and health assistants who handle clerical and phone communication duties. Patients have referral access to on-site non-medical services described above, including addictions treatment, housing referrals, and behavioral health. In 2015, OTC introduced embedded CHW workers in partnership with a regional Medicaid payor [2]. The CHWs have training in addictions or mental health counseling and engage HCHN patients outside the clinic setting. Activities of the CHW include motivational interviewing, case management, advocacy, facilitation of multi-disciplinary care planning, collaboration with primary care, and individual resource building for short-term (< 6 months) engagement.

Measurement

Data collection

The RA administers baseline and follow up surveys to participants using paper questionnaires and then enters responses into a REDCap database designed with branching logic, range checks, and forced functions to increase data quality. The RA is independent from the clinical teams to decrease risk of social desirability bias in survey response. The RA stores paper questionnaires in a locked file cabinet on site in case of discrepancies in the REDCap database. We use administrative data to examine care utilization outcomes. If a participant is lost to follow up or does not engage with the care team, we will still be able to obtain inpatient and outpatient utilization data.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is total inpatient hospitalizations at 6 and 12 months after study enrollment as assessed by PreManage, a consortium of local state and cross-state hospitals that sends in real-time hospital administrative event information (inpatient admissions and discharges, ED visits) to health plans and provider groups.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes are ED utilization at 6 and 12 months after study enrollment, and patient reported activation at 6 and 12 months of the intervention. We assess patient activation using the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-13) [28, 29], a validated tool used widely in research to assist in tailoring care plans, and evaluation assessment.

Exploratory outcomes

We will also consider pre-specified, exploratory outcomes (Table 1). We will use PreManage to calculate average length of stay per inpatient hospitalization; mortality (based on chart record review); outpatient clinic visits; and housing status (assessed using a self-reported survey question: “Which of the following best describes your current residence?”) at 6 and 12 months. We assess patient experience of healthcare at 6 and 12 months using the Consumer Assessment Healthcare Professionals (CAHPS); [30] we also assess patient reported quality of life using the SF-12 survey [31], a single item palliative care measure (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) [32], and a six-item life chaos measure by Wong that assessed self-reported ratings of participants’ routines and daily activities [33]. We will assess the impact of SUMMIT on all OTC clinical staff by assessing a two-item burnout measure periodically during implementation [34].

Socio-demographic and other potential covariates

Self-reported socio-demographic variables include age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational attainment, and annual household income. Part of the motivation for this study is to learn more about these patients and determine how psychosocial factors, of which little are captured in health records or administrative data, play a role in their healthcare experiences. Therefore, we also assessed perceived social support [35], current living situation, self-reported health literacy [36], and food insecurity [37]. We also screen for depression using the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) [38], cognitive impairment using telephone interview for cognitive status (TICS) [39], and drug and alcohol use disorders using the drug abuse screening test (DAST) and the alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT) [40]. Measures were proposed during planning meetings, and pilot tested prior to finalizing.

Sample size calculations

We conducted several sample size calculations to estimate the study size population.

We examined the sample size necessary to demonstrate a 40% reduction in our primary outcomes of hospital utilization over 6 months. We determined average number of hospitalizations over the prior 6 months for a pilot sample of SUMMIT patients (2.3 hospitalizations/person over 6 months, SD = 1.9). Assuming 80% power and 2-tailed alpha, the sample size estimated was 140 participants. Based on preliminary data, we believed 400 existing patients met SUMMIT eligibility for utilization, but targeted an enrollment of 200 based on potential difficulties with recruitment and retention. We used prior literature to determine an effect size of a four-point increase on the secondary outcome of PAM score, with standard deviation of 10; therefore, at 80% power and 2 tailed alpha, the sample size estimated was 196 [41].

Statistical analyses

We will use descriptive statistics to describe the study population and assess similarity of baseline characteristics between study arms using Chi square, t-tests, and Fisher’s exact test. For each outcome, we will conduct intent-to-treat analyses using difference-in-differences regression to compare the study arms during baseline and 6-months and 12-months follow up [42]. Use of a wait-list control design permits two methodologies to assess outcome changes. The first analysis will be a comparison of intervention and control group outcomes at 6-months, adjusting for any baseline covariates that differ by chance in each group. The second analysis will use the wait-list control to conduct a repeated measures analysis controlling for calendar time to account for secular changes in the intervention and enhanced usual care groups over time. We also plan to conduct pre-specified sub-group analyses to identify which SUMMIT patients benefit most from the intervention as currently constructed, including: study participants with only medical complexity; participants with active/primary substance use disorders; and participants who have housing instability at enrollment. Though these subgroup analyses will likely be underpowered, they may inform refined referral criteria or assist in a refined intervention.

Qualitative and formative evaluation

In addition to the primary evaluation, we are conducting qualitative interviews with clinical staff members and patient participants to explore how the intervention evolves over time and gain insights for what intervention activities worked well and what can be improved. We are conducting formative evaluation through quantitative and qualitative methods to describe intervention components, assess fidelity, and develop lessons learned [43]. This includes tracking number of visits to medical, mental health, pharmacy, nursing providers, tracking whether patients received SUMMIT core activities, and documenting issues affecting implementation of the program as intended.

Data monitoring

The research team will produce administrative reports on a quarterly basis that describe study progress including: accrual, demographic, study subjects status, outstanding REDCap study forms, error rate pertaining to adherence to inclusion/exclusion criteria and the study protocol. These reports will be reviewed internally for ongoing quality control and submitted at the request of the IRB.

Discussion

This paper describes a partnered approach to design and evaluation of a novel intensive A-ICU model of primary care for medically and socially complex patients at an FQHC clinic primarily serving low-income patients experiencing homelessness or substance use disorders. The results of this study will contribute to an evolving literature on intensive primary care interventions that addresses two gaps: (1) a need for more practiced-based research studies that include control populations; and (2) a focus on HCHN patients with high rates of homelessness and substance use.

While there is interest in improving quality of care and lowering costs for HCHN patients, how to achieve this is unclear. Intensive primary care interventions are an approach popularized by Camden Coalition’s “Hotspotters” [44] and others like it; however, there are few published evaluations to support investing resources into these models. There are several reasons why these studies do not get published. Many of these intervention programs lack resources or expertise to conduct formal evaluations and dissemination activities—often, programs are implemented, and community partners move on to the next pressing need. Another reason is that multi-component interventions like those for HCHN patients are difficult to describe and vary depending on local context [13, 45]. Patients affected by poverty, homelessness, and substance use are understudied, and have stigma associated with research participation that makes traditional clinical trial participation challenging. Our study protocol addresses these limitations by using a community-partnered approach and embedded researchers that meets both programmatic and research needs.

The wait-list randomized control design of the SUMMIT evaluation offers a balance between research and practice priorities. From a research perspective, incorporating randomization to a control group allows the study to address potential bias resulting from regression to the mean, and minimizes confounding that is present in pre-post designs. From a programmatic perspective, the wait-list control design meets the needs of clinical priorities in that all participants who are accepted have the opportunity to receive the intervention, and allow for gradual scaling up of the intervention over time to meet staff capacity [46, 47]. If the trial is successful, this study design may serve as a model for future evaluations of multi-component, interdisciplinary, practice-based evaluations of interventions for HCHN populations in other settings.

Use of this design is not without trade-offs, including accounting for extended follow-up time that may increase risk for attrition [22]. We limited the wait-list to 6 months and ask for multiple sources of contact information from participants at baseline to help decrease this risk; however, assessing primary and secondary outcomes at 6 months may be too short a time period to detect noticeable differences in utilization and self-efficacy because behavior change interventions often take up-front investments and require extended time horizons (i.e. multiple years) to demonstrate efficacy [48, 49]. Implementing practice-based research often leads to conflicts between research and practice, and our experience has been no exception; however, use of embedded researchers familiar with the patient population and clinic culture, and incorporating input from stakeholders was beneficial for evaluation planning.

In conclusion, we are testing a novel model of primary care using multi-disciplinary teams with reduced panel size and increased flexibility as an intervention to improve quality of care for patients with multiple chronic medical and social complexity. The outcomes of the SUMMIT study will provide real-world evidence about the efficacy of an A-ICU model of care for HCHN patients particularly sensitive to social determinants of health.

References

Cohen S, Yu W. The concentration and persistence in the level of health expenditures over time: estimates for the U.S. Population, 2008–2009. Statistical Brief #354 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD 2012.

Hong CS, Siegel AL, Ferris TG. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients: what makes for a successful care management program? Issue Br. 2014;19:1–19.

Wensing M, Vingerhoets E, Grol R. Functional status, health problems, age and comorbidity in primary care patients. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehabilit. 2001;10:141–8.

Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–5.

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:161–7.

Freund T, Wensing M, Mahler C, et al. Development of a primary care-based complex care management intervention for chronically ill patients at high risk for hospitalization: a study protocol. Implement Sci IS. 2010;5:70.

Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:178–87.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1822–8.

Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999;281:613–20.

Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Long JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff. 2013;32:1196–203.

Hong CS, Abrams MK, Ferris TG. Toward increased adoption of complex care management. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:491–3.

Yee T, Lechner, AE., Carrier E. High-intensity primary care: lessons for physician and patient engagement. (National Institute for Health Care Reform Research Brief No 9). http://www.nihcrorg/High-Intensity-Primary-Care. Accessed Nov 12, 2015 2012.

Edwards ST, Peterson K, Chan B, Anderson J, Helfand M. Effectiveness of intensive primary care interventions: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:1377–86.

O’Toole TP, Johnson EE, Aiello R, Kane V, Pape L. Tailoring care to vulnerable populations by incorporating social determinants of health: the veterans health administration’s “homeless patient aligned care team” program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2016;13:E44.

Hunter G, Yoon J, Blonigen DM, Asch SM, Zulman DM. Health care utilization patterns among high-cost VA patients with mental health conditions. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:952–8.

London JA, Utter GH, Battistella F, Wisner D. Methamphetamine use is associated with increased hospital resource consumption among minimally injured trauma patients. J Trauma. 2009;66:485–90.

Hwang AS, Atlas SJ, Hong J, et al. Defining team effort involved in patient care from the primary care physician’s perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:269–76.

Davis MM, Keller S, DeVoe JE, Cohen DJ. Characteristics and lessons learned from practice-based research networks (PBRNs) in the United States. J Healthc Leadersh. 2012;4:107–16.

Greene SM, Reid RJ, Larson EB. Implementing the learning health system: from concept to action. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:207–10.

Chang ET, Zulman DM, Asch SM, et al. An operations-partnered evaluation of care redesign for high-risk patients in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA): study protocol for the PACT Intensive Management (PIM) randomized quality improvement evaluation. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;69:65–75.

Handley MA, Schillinger D, Shiboski S. Quasi-experimental designs in practice-based research settings: design and implementation considerations. J Am Board Family Med JABFM. 2011;24:589–96.

Ratanawongsa N, Handley MA, Quan J, et al. Quasi-experimental trial of diabetes self-management automated and real-time telephonic support (SMARTSteps) in a medicaid managed care plan: study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:22.

Englander H, Michaels L, Chan B, Kansagara D. The care transitions innovation (C-TraIn) for socioeconomically disadvantaged adults: results of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:1460–7.

Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the improving addiction care team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2017;12:339–42.

Use the Teach-Back Method: Tool #5. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD.

Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, Group C. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:295–309.

Shippee ND, Shah ND, May CR, Mair FS, Montori VM. Cumulative complexity: a functional, patient-centered model of patient complexity can improve research and practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:1041–51.

Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1918–30.

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1005–26.

Centers for M, Medicaid Services HHS. Medicare program; hospital outpatient prospective payment system and CY 2007 payment rates; CY 2007 update to the ambulatory surgical center covered procedures list; Medicare administrative contractors; and reporting hospital quality data for FY 2008 inpatient prospective payment system annual payment update program–HCAHPS survey, SCIP, and mortality. Final rule with comment period and final rule. Federal register 2006;71:67959–8401.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33.

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The edmonton symptom assessment system (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:6–9.

Wong MD, Sarkisian CA, Davis C, Kinsler J, Cunningham WE. The association between life chaos, health care use, and health status among HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1286–91.

Rafferty JP, Lemkau JP, Purdy RR, Rudisill JR. Validity of the Maslach burnout inventory for family practice physicians. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42:488–92.

Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, et al. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:3106–16.

Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36:588–94.

Hager ER, Quigg AM, Black MM, et al. Development and validity of a 2-item screen to identify families at risk for food insecurity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e26–32.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

de Jager CA, Budge MM, Clarke R. Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18:318–24.

Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Gleason JR. Use of the AUDIT and the DAST-10 to identify alcohol and drug use disorders among adults with a severe and persistent mental illness. Psychol Assess. 2000;12:186–92.

Maindal HT, Sandbaek A, Kirkevold M, Lauritzen T. Effect on motivation, perceived competence, and activation after participation in the “Ready to Act” programme for people with screen-detected dysglycaemia: a 1-year randomised controlled trial, Addition-DK. Scand J Pub Health. 2011;39:262–71.

Ryan AM, Burgess JF Jr, Dimick JB. Why we should not be indifferent to specification choices for difference-in-differences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50:1211–35.

Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, et al. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S1–8.

Gawande A. The Hot Spotters. New Yorker. January 2011. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2011/01/24/the-hot-spotters. Accessed 1 July 2017.

Komro KA, Flay BR, Biglan A, Wagenaar AC. Research design issues for evaluating complex multicomponent interventions in neighborhoods and communities. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6:153–9.

Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:215–20.

Johnson TL, Rinehart DJ, Durfee J, et al. For many patients who use large amounts of health care services, the need is intense yet temporary. Health Aff. 2015;34:1312–9.

Ekdahl AW, Alwin J, Eckerblad J, et al. Long-term evaluation of the ambulatory geriatric assessment: a frailty intervention trial (AGe-FIT): clinical outcomes and total costs after 36 months. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17:263–8.

Meret-Hanke LA. Effects of the program of all-inclusive care for the elderly on hospital use. Gerontol. 2011;51:774–85.

Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2015;38:506–14.

Roccaforte WH, Burke WJ, Bayer BL, Wengel SP. Validation of a telephone version of the mini-mental state examination. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:697–702.

Weidmer BA, Brach C, Slaughter ME, Hays RD. Development of items to assess patients’ health literacy experiences at hospitals for the consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems (CAHPS) hospital survey. Med Care. 2012;50:S12–21.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and study design: BC, SE, MM, HE, CN, DK, SS, TK. Manuscript drafting/critical revision: BC, SE, MD, RG, HE, CN, DK, SS, TK. Final approval: BC, SE, MD, RG, MM, HE, CN, DK, SS, TK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like acknowledge Dr. Rachel Solotaroff, CEO Central City Concern for support of the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the OHSU IRB in 2016 (IRB 15285).

Funding

Dr. Chan’s time was supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12HS022981). Dr. Korthuis’ time was supported through grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (UG3DA044831, UG1DA015815, R01DA037441). The funding source played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, B., Edwards, S.T., Devoe, M. et al. The SUMMIT ambulatory-ICU primary care model for medically and socially complex patients in an urban federally qualified health center: study design and rationale. Addict Sci Clin Pract 13, 27 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-018-0128-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-018-0128-y