Abstract

Background

Most studies on plant invasion consider the enemy release hypothesis when analyzing native habitats. However, the lower performance of invasive species in the native habitats can be the result of unfavorable soil conditions in the native habitats. While soil biotic and abiotic factors have a potential to restrict the growth of invasive species in their native habitats, our understanding of belowground environment of invasive species in their native habitats is very limited. In this study, we analyzed soil characteristics associated with an exotic invasive plant, Old World Climbing Fern (Lygodium microphyllum), in its native habitat in Australia and the recipient habitat in South Florida. Rhizosphere soil samples from both habitats were analyzed for soil physical, chemical and biological characteristics.

Results

Soil characteristics in the recipient habitats were significantly different compared to those in the native habitats. Soil samples from the native habitat had low soil pH, and high concentrations of elements such as aluminum and zinc which are phytotoxic in acidic soil environments. Additionally, mycorrhizal fungi spores were more diverse in the recipient habitat in Florida compared to the native habitat in Australia.

Conclusion

Overall, our results indicate that growth of an invasive plant in its native habitats could be restricted by the toxic effects associated with strong soil acidity. Results from this study indicate that invasive plants not only escape from their natural herbivores but also from toxic soil environment in their native habitats.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Biotic and abiotic interactions of exotic invasive plants at both below and above ground can vary significantly in the native and recipient habitats. The potential of any exotic species to invade a new habitat generally depends on abiotic tolerance (Alpert et al. 2000; Levine et al. 2004), biotic resistance (Case 1990; Levine et al. 2004; Bogdziewicz et al. 2019), and propagule pressure (Lockwood et al. 2005; Simberloff 2009), or the combination of these three factors (Byun et al. 2018). Most research on exotic invasive species is focused on plant traits such as high growth rate, short lifecycle, high levels of resource allocation to reproduction, and flexible utilization of available environmental resources. Several studies with biogeographic comparison of invasive species in their native range and invaded range focus on the impact of variable soil microbes on plant performance (Callaway and Aschehoug 2000; Hierro et al. 2005; Vermeij et al. 2009; Volin et al. 2010). While there is increased research interest in the microbiome of invasive species (Coats and Rumpho 2014; Kamutando et al. 2019; Ramirez et al. 2019), there is limited information on the performance of invasive plants in their native habitats and the restrictions posed by the soil characteristics. For example, soil pH has complex effect on plant growth leading to the variation in the distribution of plant species in acidic or calcareous soils. Diekmann and Lawesson (1999) reported that pH is one of the major underlying variables determining the floristic variation within forest communities. In addition, soil acidity can result in toxicities of aluminum and manganese and deficiencies or low availability of certain essential elements including calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and molybdenum (Foy 1984). These factors may directly or indirectly restrict plant growth through interference in the development and functioning of symbiotic associations with rhizobia, mycorrhizas, actinomycetes, and other plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. It is reported that soil acidity as a result of Al toxicity has detrimental effects on plant growth by lowering rooting depth, increasing susceptibility to drought, and decreasing uptake of subsoil nutrients. Plants exposed to Al toxicity are reported to have stunted growth, small dark green leaves, late maturity, and thick root tips and lateral roots. They have many stubby lateral roots but lack in fine branching, thus, inefficient in absorbing nutrients and water (Kochian et al. 2004). Similarly, soil texture is also an important factor influencing the distribution of minerals, organic matter, microbial community, and other soil properties (Scott and Naiman 2006).

Once established, invasive species create a favorable rhizosphere conditions in the recipient habitats (Ehrenfeld 2003; Perkins et al. 2011; Coats and Rumpho 2014) and increase their fitness (Soti et al. 2019). While it is generally unlikely to eliminate invasive plant species, the recipient habitats can probably be managed to maximize the performance of native species relative to that of invaders by altering resource levels and disturbance regimes (Daehler 2003). Information on the soil conditions, where the plant has adapted, can provide a key insight in integrating environmental manipulations into the habitat restoration projects, but the comparative analysis soil characteristics in the native habitat of an invasive species remain largely unexplored.

Here, we analyze the role of soil chemistry in the successful invasion of south Florida’s natural communities by a highly invasive plant species, Lygodium microphyllum (Old World climbing fern). L. microphyllum is an invasive exotic plant species taking over many sites in freshwater and moist habitats across southern and central Florida. In the invaded regions of South Florida L. microphyllum displays most of the ecological characteristic associated with successful invasive plants (Westbrooks 1998): it has the ability to grow in varying hydrological (Gandiaga et al. 2009), nutrient (Volin et al. 2010), and light conditions (Volin et al. 2004). It tolerates a wide range of soil pH (Soti et al. 2014, 2015), and has a strong symbiotic relationship with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (Soti et al. 2014). Comparative analysis of soil samples from both its native range and invaded region have shown that L. microphyllum, which had adapted to close-to-neutral soils in Florida, grows in highly acidic soils in its native range in Australia (Soti et al. 2014). Additionally, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) world soil distribution map shows the soil in the native range, identified by Goolsby et al. (2003), is a region with high soil acidity. Volin et al. (2010) indicated that the growth of L. microphyllum was highest in sandy soils which indicates that this plant prefers well drained sandy soils. Furthermore, the root and rhizome growth of L. microphyllum was highest in the sandy soils of south Florida compared to the native Australian soils.

L. microphyllum does not have a high economic value in its native range, thus there is very little information available about its native ecology, and the available information is mostly on its native herbivores. Very little is known about why this plant is invasive outside its native range (Ferriter 2001). In the invaded regions in South Florida, L microphyllum is highly invasive and current management techniques such as fire, herbicides, and mechanical removal are inadequate. The prospect of developing a method that targets the rhizomes of L. microphyllum is compelling; however, the soil biogeochemical characteristics of L. microphyllum infested sites remain unexplored. Before we target the rhizomes, it is imperative to elucidate the soil characteristics of the sites, where this plant has adapted, to obtain baseline information. Additionally, it is important to gain information of the soil characteristics of the native range where this plant has its origin and adapted habitat. Results from this study will assist in better understanding of the complex feedbacks between exotic invasive plants, soil microbial community and soil elements.

To determine if L. microphyllum escaped from the toxic soil conditions and natural soil enemies, we explore the variation in the biotic and abiotic soil characteristics of L. microphyllum from both the native and recipient habitats. We hypothesized that the rhizosphere soil in the native habitat is generally poor in nutrients and high in phytotoxic elements such as Al compared to the recipient habitat in Florida.

Methods

Sites selection

We compared soil samples collected from three different sites each in Queensland, Australia, where the plant species is native, and in Florida, United States, where L. microphyllum is a Category I exotic invasive ([FLEPPC] Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council 2019). Queensland and South Florida have similar climate conditions such as average monthly maximum and minimum temperatures, rainfall amounts, rainfall pattern, and relative humidity (for details see Goolsby et al. 2003). In its native Australian sites, L. microphyllum grows around the edges of Melaleuca quinquenervia, a major invasive plant in the South Florida or edges of swamps along with Drynaria sp. and Blechnum indicum. In the recipient habitat Florida, the plant has adapted to multiple hydrologic conditions. The three study sites in Florida were selected based on the different habitat conditions: (1) Tree Tops Park, a highly disturbed habitat which is seasonally flooded, with L. microphyllum growing in the understory; (2) Jonathan Dickinson State Park, is relatively undisturbed habitat with sand pine scrub communities. Here, L. microphyllum grows to the top of the canopy of trees; and (3) Central Florida site, a private property with sand mine spoil dominated by L. microphyllum and a few native ferns.

Sample collection

Soil samples were collected during the dry season in both continents (Table 1, Fig. 1), except for the Central Florida site (which was added later at the request of Nature Conservancy). At each sampling site, six 1 m × 1 m plots were selected randomly, and soil from the 10–15 cm deep zone was collected from all four corners and the center of each plot with a soil corer (diameter: 18 mm) and mixed homogeneously into one bulk sample for each plot, resulting in six composite soil samples from the six different sites in the two habitats. The soil samples from the local sites in South Florida were transported to the laboratory in a cooler, and samples from Australia and Central Florida were stored in 4 °C and shipped overnight.

Soil nutrient analysis

A small portion of each soil sample was air dried and passed through a 2 mm sieve for analysis of physicochemical properties. They were ground to fine powder with a mortar and pestle and stored at room temperature in air-tight containers for further analysis of nutrients and trace elements. The soil pH was measured with a pH meter (soil solution ratio 1:2 in water), texture was measured by the hydrometer method (Bouyoucos 1962), and total organic matter was measured based on the standard loss on ignition method (500 °C, 5 h; Storer 1984). Total C and N in soil and leaves were measured with a Truspec CN analyzer. Total Ca, Fe, Al, Mg, K, Mn and P in soil were measured with an ICP–MS at USDA, ARS Laboratory, Miami, Florida after following the acid digestion Method 3050B (USEPA Method 3050 1996). One gram of finely ground soil samples was transferred to large glass tubes and mixed with 10 ml of 30% HNO3. The tubes were covered with a vapor recovery system and heated to 95 ± 5 °C and refluxed for 10 min without boiling under the hood in a heating block maintained with a Partlow Mic 6000 Profile Process Controller.

After cooling to 40 °C, 5 ml of concentrated HNO3 was added and the samples were then heated at to 95 ± 5 °C until no brown fumes were given off. The samples were again cooled to 40 °C, 2 ml of DI water and 3 ml of 30% H2O2 were added and heated until the effervescence subsided. The samples were cooled and diluted to 50 ml with DI water, centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min and filtered with a Whatman No. 41 filter paper.

Microbial analysis: bacteria and fungi population

Total colony forming units (CFU) of bacteria and fungi was determined by the standard spread plate dilution method as described by Seeley Jr and VanDemark (1962). Dry equivalent of one-gram soil was mixed in 9 ml sterile water (autoclaved) and was diluted serially. Samples were vigorously mixed during dilution to assist in dislodging the bacteria from the soil particles. A serial dilution of 10− 2, 10− 3, 10− 4, and 10− 5 was made for fungi and 10− 4, 10− 5, 10− 6, and 10− 7 for bacteria. A total of 100 μl of diluted soil suspension was spread on three plates per soil sample for both bacteria and fungi at each dilution level. Nutrient agar containing cycloheximide solution (to prevent fugal growth) was used for bacteria and Rose Bengal Agar (RBA) with streptomycine sulphate (to prevent bacteria growth) was used for the estimation fungal colonization. Agar plants with spread with sterilized water were used as control. Inoculated plates were incubated at 26 °C for 3 days before the colonies were counted. Dilution plates with 100 to 300 colonies per plate were counted.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) spore extraction and identification

Results from our previous study indicated that the mycorrhizal root colonization in L. microphyllum is significantly higher in the invaded regions compared to the native regions in Australia (see Soti et al. 2014). In this study, we identified the morphospecies of AMF sproes in the rhizosphere soil of L. microphyllum in both the regions following the wet sieving technique (Gerdemann and Nicolson 1963). 100 ml of DI water was added to dry equivalent of 50 g of soil from each site. It was then mixed vigorously to separate the spores from soil aggregates. The mixture was washed through a series of sieves (2 mm, 100 μm and 32 μm). Washing was done until the water flowing through the sieves was clear. The sievate retained on the sieves was washed and centrifuged with water to remove floating organic debris and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet in the bottom was re-suspended in a 50% sucrose solution and centrifuged for one minute at 2000 RPM to separate the spores from denser soil components. Immediately after centrifugation, spores in the sucrose supernatant were rinsed in a fine sieve to remove the sucrose. The spores were then washed into a filter paper for vacuum filtration. The fungal spores were then mounted on slides for taxonomic identification to the genus level based on the spore morphology and wall characteristics, using the descriptions by INVAM (International culture collection of vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi) (n.d.). The genus that was dominant was taken as the representative mycorrhizal AMF type for each site.

Statistical analysis

All soil variables were subjected to normality test. The data was not normalized with transformation, so a non-parametric test was conducted. Kruskal-Wallis test was done to compare the difference in the rhizosphere soil status of L. microphyllum among the different sites. Contrasts were done to test the difference among sites with the overall model was significant. Pearson’s correlation analysis and was done with all sites pooled to determine relationship between the measured soil variables. Differences are reported as significant for tests with P-values ≤0.05. All the parameters were analyzed with SAS Version 9.2 software.

Results

Soil chemical and physical properties

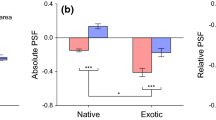

Soil properties in the study sites were highly variable and site specific (Tables 2, 3; Fig. 2). Soil texture, shown in Table 2, varied significantly among the different sites with native sites having heavier soils (high bulk density) compared to the recipient sites. Soil chemistry results also indicated site specific characteristics in the native and recipient habitats (Table 3; Fig. 2). The Australia sites had strong acidic soil ranging from pH = 4.1 to 4.55 while the recipient sites Florida had significantly higher soil pH ranging from 5.60 to 6.57. In general, elements which are phytotoxic in acidic soil such as Al, Zn, and Fe were higher in the native sites in Australia except for site 2, a sand mine spoil, in the recipient habitat (Fig. 2). Total C and N were highest in the recipient site, and there was no difference in P among the sites in both native and recipient habitats.

Bacteria and fungi populations

The average number of bacteria and fungi, colony forming units (CFU) per gram of dry soil, was significantly different in all six sites (Table 2). Total CFU of bacteria was highest in native habitat (288 × 106) and lowest in recipient habitat (39 × 106). Likewise, the total CFU of fungi was also highest in native site (123.5 × 103). Correlation analysis indicated that, there was no relationship between the soil organic matter, total carbon on the soil bacterial and fungal population, however there was a strong relationship with the soil texture (Table 4). Surprisingly, the bacteria population had a negative relationship with the soil pH while the fungi had no relationship with the soil pH.

AMF spores

The spore composition based on the morphology was different among the six sampling sites. Spores of different sizes and colors were present in all six sites. Highest morphological diversity was seen in the two recipient sites, and the lowest diversity was seen in recipient site 3. Spores of Glomus spp. were found in all the locations but were dominant in native site 3, and recipient site 2; spores of Scutellospora spp. were dominant in recipient site 1 and 3; and spores of Gigaspora spp. in native site 1 (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Objective of this study was to analyze the role of soil rhizosphere, soil chemistry, and biology on the success of an invasive species in the recipient habitat compared to its native habitat. While our study was limited in the number of sampling sites and sampling frequency, our results show that there was a significant difference in the soil chemical, biological as well as physical characteristics in these two habitats, native and recipient. These soil characteristics can potentially, on their own or in combination with other habitat features, promote the extensive growth of exotic invasive plant in the recipient habitat compared to its native habitat.

Our results show that L. microphyllum has adapted to nutrient poor and highly acidic soils in its native habitat. In the recipient habitat, the plant can perform equally well in acidic soils and outcompete coexisting vegetation in slightly higher pH levels. Soil pH between 5.5 to 7.5 is known to provide the optimal growing conditions for this plant (Soti et al. 2015). The recipient sites in Florida, where L.microphyllum is invasive, had the optimum soil pH range. In addition, this pH range is also optimal for AMF which has been found to enhance the growth of L. microphyllum (Soti et al. 2014). In the native sites Australia, the soil pH was significantly lower than optimal for both the plant and AMF.

Along with strong acidic conditions, the native soils also had high concentration of Al, which is considered to be phytotoxic in strong acidic soils (Delhaize and Ryan 1995; Lidon and Barreiro 2002; Kochian et al. 2005). One of the sites in recipient habitat, where L. microphyllum was growing over sand mine spoil, had the highest concentration of Al. However, this was not a restricting factor for L. microphyllum growth. Al toxicity is reported to cause alterations of physiological and biochemical process of plants and consequently in their productivity (Kochian 1995). Plant species differ in their Al tolerance, but L. microphyllum grown in Australian soil had lower biomass allocation to the belowground structures (rhizomes and roots) compared to the plants grown in Florida soils. When L. microphyllum escaped the highly acidic soil and clayey soil environment in the native habitat to the sandy and slightly alkaline soils in the new habitat, they could have acclimated to lowered investment cost in defense and reallocation of the resources to growth and reproduction, increasing their colonizing success.

Various soil and plant factors cause a significant influence in the soil microbial community, which have a fundamental role in nutrient cycling, plant growth and root health. It is widely reported that the rhizosphere community of different plant species growing in the same soil are distinct because of differences in root exudation (Badri and Vivanco 2009; Brimecombe et al. 2000). Likewise, individual plant species can harbor different microbial communities in different soil types (Yang and Crowley 2000). A strong effect of soil texture on bacteria and fungi population was evident in this study. Native sites with the highest percentage of silt harbored highest CFUs of bacteria and fungi, while Jonathan Dickinson site in Florida with 98% sand had the lowest CFUs of bacteria and fungi. This kind of influence of soil texture on the structure of microbial population has been reported previously (Garbeva et al. 2004; Fang et al. 2005). An unexpected result was, the bacteria and fungi population remained uninfluenced by the soil organic matter, total C or soil pH which indicates a possible difference in the litter quality and secondary metabolites produced by the plant in its native range and invaded community and warrants further research.

Our results indicate that L. microphyllum had a symbiotic relationship with multiple species of AMF depending on the site conditions. Our two sites, Central Florida and Tree Tops which had higher diversities of spores are relatively disturbed sites compared to the other sites which had lower diversity of spores. This is an expected result and is in line with the Intermediate Disturbance Hypothesis (IDH) (Huston 1979), which suggests that a less disturbed healthy ecosystem has lower diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. We found that Glomus sp., which is reported to be the dominant and most abundant genus of AMF, was present in all sites but dominant in the native sites in Australia and one recipient site in Florida. Spores of Scutellospora sp. were dominant in the two-recipient site with slightly higher soil pH and sandier in texture. This study provides evidence that mycorrhizal fungi spore composition is different in the native and recipient habitats along with the soil characteristics, but an in-depth analysis with the use of molecular technique is necessary to identify the AMF species and their relationship with L. microphyllum. Future studies should focus on exploring the microbial community in the sites invaded by L. microphyllum and their role in its growth and competitive ability.

Conclusions

Improved understanding of habitat characteristics of an invasive plant in its native and recipient range is important to understand whether the invaders have escaped hostile environmental conditions in their native range. Biogeographic variation in soil conditions could play an important role in the invasive success of nonnative plants in recipient habitats. Our results suggest that L. microphyllum can be growing poorly in its native range in Australia because of the soil toxic effects associated with soil acidity along with soil texture. In addition, while we were not able to determine the specific roles of the soil microbial community, difference in the microbial populations and types in the two regions could in part explain the extensive growth of L. microphyllum in the recipient habitats in south Florida. Thus, land managers should focus on soil restoration to manage the extensive growth of invasive species and increase the competitive ability of native species.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Al:

-

Aluminum

- AMF:

-

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

- C:

-

Carbon

- Ca:

-

Calcium

- CFU:

-

Colony forming unit

- DI:

-

Deionized

- Fe:

-

Iron

- ICP-MS:

-

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry

- Mg:

-

Magnesium

- Mn:

-

Manganese

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- USDA-ARS:

-

United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service

- Zn:

-

Zinc

References

Alpert P, Bone E, Holzapfel C (2000) Invasiveness, invasibility and the role of environmental stress in the spread of non-native plants. Perspect Plant Ecol Evol Syst 3(1):52–66

Badri DV, Vivanco JM (2009) Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ 32(6):666–681

Bogdziewicz M, Lichti NI, Zwolak R (2019) Consumer-mediated indirect interaction with a native plant lowers the fitness of an invasive competitor. J Ecol 107(1):12–22

Bouyoucos GJ (1962) Hydrometer method improved for making particle size analyses of soils. Agron J 54(5):464–465

Brimecombe MJ, De Leij FA, Lynch JM (2000) The effect of root exudates on rhizosphere microbial populations. In The Rhizosphere, Biochemistry and Organic Substances at the Soil– Plant Interface (eds R. Pinton, Z. Varini & P. Nannipieri), pp. 95–140. Marcel Dekker, New York

Byun C, de Blois S, Brisson J (2018) Management of invasive plants through ecological resistance. Biol Invasions 20(1):13–27

Callaway RM, Aschehoug ET (2000) Invasive plants versus their new and old neighbors: a mechanism for exotic invasion. Science 290(5491):521–523

Case TJ (1990) Invasion resistance arises in strongly interacting species-rich model competition communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci 87(24):9610–9614

Coats VC, Rumpho ME (2014) The rhizosphere microbiota of plant invaders: an overview of recent advances in the microbiomics of invasive plants. Front Microbiol 5:368

Daehler CC (2003) Performance comparisons of co-occurring native and alien invasive plants: implications for conservation and restoration. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 34(1):183–211

Delhaize E, Ryan PR (1995) Aluminum toxicity and tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol 107:315–321

Diekmann M, Lawesson JE (1999) Shifts in ecological behaviour of herbaceous forest species along a transect from northern central to North Europe. Folia Geobotanica 34(1):127–141

Ehrenfeld JG (2003) Effects of exotic plant invasions on soil nutrient cycling processes. Ecosystems 6(6):503–523

Fang M, Kremer RJ, Motavalli PP, Davis G (2005) Bacterial diversity in rhizospheres of nontransgenic and transgenic corn. Appl Environ Microbiol 71(7):4132–4136

Ferriter A (2001) Lygodium management plan for Florida: a report from the Florida exotic Pest plant Council's Lygodium task force. Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council. Recovered from https://bugwoodcloud.org/CDN/fleppc/publications/lymo_mgt.pdf in Sept 2019

[FLEPPC] Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (2019) Recovered from https://www.fleppc.org/list/list.htm in Sept 2019

Foy CD (1984) Physiological effects of hydrogen, aluminum, and manganese toxicities in acid soil. In: Adams F (ed) Soil acidity and liming. American Society of Agronomy, Inc., Madison, pp 57–97

Gandiaga S, Volin JC, Kruger EL, Kitajima K (2009) Effects of hydrology on the growth and physiology of an invasive exotic, Lygodium microphyllum (Old World climbing fern). Weed Res 49:283–290

Garbeva P, Van Veen JA, Van Elsas JD (2004) Microbial diversity in soil: selection of microbial populations by plant and soil type and implications for disease suppressiveness. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42:243–270

Gerdemann JW, Nicolson TH (1963) Spores of mycorrhizal Endogone species extracted from soil by wet-sieving and decanting. Trans Br Mycol Soc 46:235–244

Goolsby JA, Wright AD, Pemberton RW (2003) Exploratory surveys in Australia and Asia for natural enemies of Old World climbing fern, Lygodium microphyllum: Lygodiaceae. Biol Control 28(1):33–46

Hierro JL, Maron JL, Callaway RM (2005) A biogeographical approach to plant invasions: the importance of studying exotics in their introduced and native range. J Ecol 93(1):5–15

Huston M (1979) A general hypothesis of species diversity. Am Nat 113(1):81–101

INVAM (International culture collection of vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi) (n.d.), West Virginia University. https://invam.wvu.edu/

Kamutando CN, Vikram S, Kamgan-Nkuekam G, Makhalanyane TP, Greve M, Le Roux JJ, Richardson DM, Cowan DA, Valverde A (2019) The functional potential of the rhizospheric microbiome of an invasive tree species, Acacia dealbata. Microb Ecol 77(1):191–200

Kochian LV (1995) Cellular mechanisms of aluminum toxicity and resistance in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 46(1):237–260

Kochian LV, Hoekenga OA, Piñeros MA (2004) How do crop plants tolerate acid soils? Mechanisms of aluminum tolerance and phosphorous efficiency. Annu Rev Plant Biol 55:459–493

Kochian LV, Pineros MA, Hoekenga OA (2005) The physiology, genetics and molecular biology of plant aluminum resistance and toxicity. Plant Soil 274:175–195

Levine JM, Adler PB, Yelenik SG (2004) A meta-analysis of biotic resistance to exotic plant invasions. Ecol Lett 7(10):975–989

Lidon F, Barreiro M (2002) An overview into aluminum toxicity in maize. Bulg J Plant Physiol 28:96–112

Lockwood JL, Cassey P, Blackburn T (2005) The role of propagule pressure in explaining species invasions. Trends Ecol Evol 20(5):223–228

Perkins LB, Johnson DW, Nowak RS (2011) Plant-induced changes in soil nutrient dynamics by native and invasive grass species. Plant Soil 345:365–374

Ramirez KS, Snoek LB, Koorem K, Geisen S, Bloem LJ, Ten Hooven F, Kostenko O, Krigas N, Manrubia M, Caković D, van Raaij D (2019) Range-expansion effects on the belowground plant microbiome. Nat Ecol Evol 3(4):604–611

Scott BJ, Naiman RJ (2006) Soil texture and nitrogen mineralization potential across a riparian toposequence in a semi-arid savanna. Soil Biol Biochem 38(6):1325–1333

Seeley HW Jr, VanDemark PJ (1962) Microbes in action. A laboratory manual of microbiology. Microbes in action. A laboratory manual of microbiology

Simberloff D (2009) The role of propagule pressure in biological invasions. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 40:81–102

Soti P, Purcell MF, Jayachandran K (2019) Data on foliar nutrient concentration of invasive plants in the recipient habitat and their native habitat. Data Brief 25:104201

Soti PG, Jayachandran K, Koptur S, Volin JC (2015) Effect of soil pH on growth, nutrient uptake, and mycorrhizal colonization in exotic invasive Lygodium microphyllum. Plant Ecol 216(7):989–998

Soti PG, Jayachandran K, Purcell M, Volin JC, Kitajima K (2014) Mycorrhizal symbiosis and Lygodium microphyllum invasion in South Florida—a biogeographic comparison. Symbiosis 62(2):81–90

Storer D (1984) A simple high sample volume ashing procedure for determination of soil organic-matter. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 15:759–772

USEPA Method 3050 (1996) Acid digestion of sediments, sludges, and soils. Available at: <www.epa.gov/epaoswer/hazwaste/test/pdfs/3050b.pdf>

Vermeij MJA, Smith TB, Dailer ML, Smith CM (2009) Release from native herbivores facilitates the persistence of invasive marine algae: a biogeographical comparison of the relative contribution of nutrients and herbivory to invasion success. Biol Invasions 11(6):1463–1474

Volin J, Lott M, Muss J, Owen D (2004) Predicting rapid invasion of the Florida Everglades by old world climbing fern (Lygodium microphyllum). Divers Distrib 10:439–446

Volin JC, Kruger EL, Volin VC, Tobin MF, Kitajima K (2010) Does release from natural belowground enemies help explain the invasiveness of Lygodium microphyllum? A cross-continental comparison. Plant Ecol 208:223–234

Westbrooks R (1998) Invasive plants, changing the landscape of America: fact book. Federal Interagency Committee for the Management of Noxious and Exotic Weeds (FICMNEW), Washington DC

Yang CH, Crowley DE (2000) Rhizosphere microbial community structure in relation to root location and plant iron nutritional status. Appl Environ Microbiol 66(1):345–351

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Cheryl Millett, Central Florida Nature Conservancy; Patricia L. Howell, Natural Areas Specialist, Broward County; and Jeffrey Bach, Environmental Specialist, Jonathan Dickinson State Park, for their help in site selection and sample collection. We also thank staff of the USDA ARS Australian Biological Control Laboratory for assistance with sample collecting in Australia. We thank Dr. Stewart Reed, USDA-ARS, Subtropical Horticulture Research: Miami, FL, for his help in sample analysis.

Funding

This study was funded by the Dissertation Evidence Acquisition Fellowship, Florida International University to P. Soti.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P. Soti: Designed the experiment, collected and analyzed the samples. P. Soti also, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. M. Purcell: Assisted in experimental design, collected the samples in Australia, and assisted in writing the manuscript. K. Jayachandran: Assisted in experimental design, provided resources, and assisted in writing the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Soti, P.G., Purcell, M. & Jayachandran, K. Soil biotic and abiotic conditions negate invasive species performance in native habitat. Ecol Process 9, 18 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00220-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00220-1