Abstract

In this paper, we analyze the load deflection behavior of the superstructure elements of beam bridges under two different beam–beam connection designs. We present a mathematical model for beam–bridge structural analysis and apply the finite element method to solve the problem. We investigate the effects of beam–beam connection design on the response and behavior of the bridge system. We also present the effect of live-loads and dead-loads on structural deformation, stress, and internal strain energy. We perform computer modeling of the beam bridge using ANSYS 19.2.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Bridges have always been an important part of our communities since the beginning of human civilization. The main objective of bridge construction is providing passages over natural barriers such as rivers and valleys, or infrastructures such as roads and railways. In modern bridge engineering, bridges can be classified by several different approaches, such as functions, materials, and types of structural elements. The notable bridge types include beam bridges, truss bridges, cantilever bridges, arch bridges, and suspension bridges [6]. The beam bridge is the most common form that has been used more extensively than others. Beam bridges or girder bridges are the simplest and also the oldest type of bridges. Similarly to many kinds of physical structures such as ships or building, they involve two components, superstructure and substructure. The superstructure refers to the beam itself, where the live load such as traffic loads are endured, and the substructure refers to a supporting structure to the bridge such as foundation, abutment, and piers where the live loads, dead load, and other loads are tolerated [14]. In their most basic form, beam bridges usually consist of a relatively short horizontal beam with supports at each end.

When multiple beams are continuously connected, piers are used as the intermediate supports. However, the distance between piers needs to be carefully calculated because it affects the robustness of the bridge. Development of a beam bridge essentially adds a significant structure in a form of large steel or iron beam called girder. The girder provides a stronger support to the concrete deck and transfers the load down to the foundation. Generally, there are two types of broadly used girders including I-beam girders and box-girders. There are two main types of beams, H- and I-type beams, as shown in Fig. 1. As the name suggests, the I-beam girders take the form of the capital letter I, where the top and bottom plates are known as flanges, and the middle plate is named as a web. The same applies to the box-girders, but instead of having one web located at the middle of two flanges, there are multiple webs between two flanges assembling numerous chamber box girders [17].

Correctly locating construction joints is important for stability of the structure. Expansion joints are generally placed at various intervals to allow for the expansion/contraction of the material of the bridge. Beam–beam joints are commonly located at the beam–column intersection where shear forces are low. Many bridge problems happen due to improper bridge element connection as shown in Fig. 2. Problems commonly occurring in bridges include damaged bearings caused by drainage through failing joint, deteriorated steel superstructure caused by leaky or missing joint seals, and pier deterioration from joint leakage.

The use of structural modeling and analysis plays a crucial role in predicting and determining the load-deflection behavior. For evaluation of existing bridges, structural models such as lumped-parameter models (LPMs), structural component models (SCMs), and finite element models (FEMs) are used to study the internal forces, stresses, and fracture of structures under various load conditions. Especially, the finite element method has been remarkably used in the area of structural analysis over the past 60 years. The finite element analysis (FEA) is also used in an accuracy assessment of the design rules [16]. A growing body of research has numerically investigated the structural performance of different types of bridges and their components exposed to various loadings using FEMs. A study on the ultimate load behavior of slab on a steel stringer bridge superstructure using a three-dimensional nonlinear finite element analysis based on the ABAQUS software was conducted by Barth and Wu [2].

Brackus et al. [3] used both experimental and numerical models to determine the load distribution between the steel girders and the precast deck panels. They found that the load-deflection data obtained from their numerical analysis corresponded very well with experimental results. Cobo del Arco and Aparicio [4] formulated a set of governing equations to study the deflection behavior of suspension bridges under concentrated loading. Nakamura, Tanaka, and Kazutoshi [13] carried out a static analysis of a new type of bridge called the cable-stayed bridge with concrete filled steel tubes (CFT) arch ribs. They compared structural deformation between the cable-stayed CFT arch bridge and a conventional steel cable-stayed bridge at various ultimate loads. It was found that the cable-stayed CFT arch bridge has higher flexural rigidity with less deflection than the conventional bridge.

The superstructure of the bridge usually consists of multiple spans to prevent any possible cracking. Due to the importance of the connections of bridge elements, a great deal of research has been carried out, based on both experimental and numerical models, to study the behavior of beam-to-column connections and beam-to-beam connections. Mashaly et al. [11] studied numerically the behavior of beam-to-column joints in steel frames subjected to lateral loads using a 3D finite element model. Zhu and Li [19] used beam-to-column welded connections in steel structures to study the resistance of steel structure after a fire. Jia et al. [8] performed experiments to investigate the effects of gusset stiffeners at the beam-web-to-column-web joint on seismic performance of the beam–column connections in existing piers with welded box sections. Liu et al. [9] investigated experimentally the weld damage behavior using various local welded connections representing beam-to-column connections under monotonic and cyclic loads. As the beam-to-beam connection plays a tremendous part in the deformation of the bridge, several studies [5, 18] on beam-to-beam connections have been carried out. Dessouki et al. [5] performed bolt force analysis using two different designs of end-plate configurations, four bolts and multiple rows extended end plates, for I-beam extended end-plate moment connection. Yam et al. [18] analyzed the block shear strength and behavior of coped beams with welded end connections using the finite element model. However, no attempt has been done on the structural analysis of the beam bridge with main beam connections.

Hence the objective of this paper is to study the load-deflection behavior of beam bridges with connections on the main beams. A finite element model of the beam bridge structure is presented to analyze the structural behavior of the beam bridge with main beam connections under dead-load and live-load forces. The model is used to conduct a parametric study on two different designs of the connections including the full beam–beam and the half beam–beam geometries. Effects of the connection design on bridge behavior are investigated. We also present the total deformation, distributions of equivalent (von Mises) stresses, and internal strain energy obtained from the domain with different beam-to-beam connection geometries.

2 Governing equation

Deformation of bridge structure can be described by a 3-D elasticity equation based on equilibrium state [1]. First, the total potential energy is defined as the difference between the strain energy U and the potential energy of external forces V, that is,

From the principle of virtual work, a small change of the internal strain energy δU is offset by an equal amount of change in external work δV due to the applied load. The principle of minimum potential energy states that the total potential energy is minimized in the state of stable static equilibrium, that is,

where Δ is a virtual operator. The strain energy due to the material deformation is defined by

where \(\underline{\varepsilon}\) and \(\underline{\sigma}\) denote, respectively, the strain and stress vector, and Ω represents the computational domain. In this paper, we assume that all materials of the bridge components are isotopic and linearly elastic, and the properties of all materials are determined at an average temperature. Thus, the stress–strain relationship [7] is

where D is the elastic matrix, which depends on the Lamè constant λ and μ by

where \(\lambda=\frac{E \nu}{(1+\nu)(1-2\nu)}\)) and \(\mu=\frac{E}{2(1+\nu )}\) with Young’s modulus E and Poisson’s ratio ν.

The relation between the strain and the displacement field is

where \(\underline{w}\) is the displacement vector in the material.

In finite element modeling the computation domain Ω is divided into a finite number of elements \(\varOmega_{e}\). Let N be the element shape function. Then the nodal displacement vector \(\underline{u}\) is related to the displacement vector within the element by

where B is the strain displacement matrix, which can be determined from equations (5) and (6).

Hence from equations (3), (4), and (7) the total virtual strain energy is

Due to the unit virtual displacement, the external virtual work ΔV is composed of the inertial effect \(\Delta V_{1}\) and the pressure force acting on the material surface \(\Delta V_{2}\). Let F be the acceleration force vector. Then the inertial effect can be determined by

and, according to Newton’s second law,

where ρ is the density (mass per unit volume) and t is time. The pressure force acting on the element surface is given by

where P is the applied pressure vector, and \(S_{p}\) is the area over which pressure acts. From equations (9)–(11) and (6) we get

Combining equations (1), (2), (8), and (12) gives the equilibrium equation

where u and \(\underline{\ddot{u}}\) denote displacement vector and its acceleration, and

The beam bridge to be analyzed is divided into a finite number of elements, which are assembled at nodes. The assembly finite element equations are subsequently solved to determine the response of the beam bridge to the following set of boundary conditions:

-

Each I-beam is pinned to its support.

-

The bases of all footings do not experience any deflection, that is, \(\underline{u} = \underline{0}\).

3 Finite element simulation

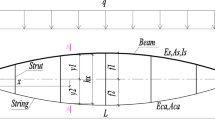

In this study, we consider the 3-span beam structure of Bridge No. 1223 with a width of 6.8 meters and length of 51.2 meters. The lengths of the three spans are 17.10, 16.96, and 17.10 meters, respectively. The bridge carries two lanes of traffic and footpath area. Figure 3 shows the main parts of the bridge. The bridge structure consists of a set of 24 steel I-beams, a concrete floor slab with a thickness of 15.24 mm, an asphalt concrete road of 60-meter length, two concrete footpaths, four pier caps, 16 pier columns, and 16 foundation footings. The pier caps, pier columns, and foundation footings are made of reinforced concrete. Table 1 shows the material properties including the density and various elastic moduli, such as Young’s modulus, the shear modulus, and the bulk modulus at temperature 22°C. Table 2 lists the weights of three different types of trucks including light, medium, and heavy trucks.

To analyze the beam-structure response under dead-load and live-load forces, the finite-element structural model was developed. Two different geometries of beam-beam connection, the half-full beam–beam shape and half beam–beam shape as shown in Fig. 4, are introduced. Due to the weight of the footpath, the dead-load 1386 N/m2 is applied on the top surface of each footpath. The live-load force is applied when two identical trucks are driven across the bridge. In this study, two medium trucks with the weight of 7258 kg are assumed to be driven at a constant speed of 60 km/h on each lane of the traffic. We assume that both trucks are to arrive and depart the bridge at the same time. We also apply a fixed support on the bottom surface of all foundation footings.

Computer modeling of the beam bridge with multiple connections was performed using ANSYS 19.2. The numerical simulation starts at \(t=0\) s and finishes at \(t=3\) s. For studying the structural response of the beam bridge under dead- and live-load forces, the analysis of bridge deformation is essential. Figure 5 presents the total deformation of the bridge structure with the half beam–beam shaped connections. The surface deformation plots show the deformation behavior of the bridge at three instants of time, \(t=0.16\) s, 16 s, and 2.8 s. The deformation profiles show the maximum, average, and minimum magnitudes over time. The deformation plot illustrates that the values around the beginning and the end of the bridge, at \(t=0.16\) s and \(t=2.8\) s, are small while the values around the bridge center are large when both trucks arrive the bridge center at around \(t=1.6\) s. The values of the deformation are between 0.03154 mm and 0.15454 mm, and its average values are between 0.0705 mm and 0.04525 mm.

To investigate the effect of the geometry of beam–beam connection, we plotted the load-deflection behavior including the total deformation, the equivalent (von Mises) stress and the total strain energy over time, as shown in Figs. 6, 7, and 8. For the bridge model with the half-full beam–beam-shaped connection, the deformation, the stresses, and the total strain energy are significantly higher than those obtained from the bridge model with half beam–beam connections. The maximum and minimum values of the deformation, stresses, and the total strain energy for the bridge with different types of connections are also presented in Table 3.

4 Conclusion

The computer bridge model was developed to study the effect of beam–beam connection geometry on the load-deflection behavior of beam bridges. Two designs of half-full beam–beam shape and half beam–beam shape were chosen in this study. The results indicate that the model with half-full beam–beam connection design leads to higher values of bridge deformation, (von Mises) stress, and total strain energy compared with the bridge model with half beam–beam connections. The results of this research may help structural engineers in the optimization of the main I-beam connection system design.

References

ANSYS Inc.: User’s Manual R18.2: Theory Guide (2017)

Barth, K.E., Wu, H.: Efficient nonlinear finite element modeling of slab on steel stringer bridges. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 42, 1304–1313 (2006)

Brackus, T.R., Barr, P.J., Cook, W.: Live-load and shear connection testing of full-scale precast bridge panels. J. Bridge Eng. 18(3), 210–219 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)BE.1943-5592.0000343

Cobo del Arco, D., Aparicio, A.C.: Preliminary static analysis of suspension bridges. Eng. Struct. 23, 1096–1103 (2001)

Dessouki, A.K., Youssef, A.H., Ibrahim, M.M.: Behavior of I-beam bolted end-plate moment connections. Ain Shams Eng. J. 4, 685–699 (2013)

Elloboy, E.: Finite Element Analysis and Design of Steel and Steel-Concrete Composite Bridges. Elsevier, Oxford (2014)

Hughes, T.J.R.: The Finite Element Method: Linear Static and Dynamic Finite Element Analysis. Dover, Newburyport (2012)

Jia, L.-J., Ikai, T., Ge, H., Hada, S.: Seismic performance of compact beam–column connections with welding defects in steel bridge piers. J. Bridge Eng. 22(4), 04016137 (2017)

Liu, X.Y., Wang, Y.Q., Xiong, J., Shi, Y.J.: Investigate on the weld damage behavior of steel beam-to-column connection. Int. J. Steel Struct. 17(1), 273–289 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13296-015-0070-8

Luecke, W.E., McColskey, J.D., McCowan, C.N., Banovic, S.W., Fields, R.J., Foecke, T., Siewert, T.A., Gayle, F.W.: Mechanical Properties of Structural Steels. NIST NCSTAR1-3D (2005) 324 pages

Mashaly, E., El-Heweity, M., Abou-Elfath, H., Osman, M.: Finite element analysis of beam-to-column joints in steel frames under cyclic loading. Alex. Eng. J. 50, 91–104 (2011)

Murray, Y.D.: Users Manual for LS-DYNA Concrete Material Model 159. The National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161. FHWA-HRT-05-062, 89 pages

Nakamura, S., Tanaka, H., Kato, K.: Static analysis of cable-stayed bridge with CFT arch ribs. J. Constr. Steel Res. 65, 776–783 (2009)

Nilson, A.H., Darwin, D., Dolan, C.W.: Design of Concrete Structures. McGraw-Hill, Boston (2010)

Patel, A., Kulkarni, M.P., Gumaste, S.D., Bartake, P.P., Rao, K.V.K., Singh, D.N.: A methodology for determination of resilient modulus of asphaltic concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2011, Article ID 936395 (2011) https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/936395

State of California Department of Transportation: Bridge Design Practice, 4th ed. (2015) http://www.dot.ca.gov/des/techpubs/bdp.html. Accessed 22 Feb 2018

Troyano, L.F.: Bridge Engineering: A Global Perspective. Thomas, London (2003)

Yam, M.C.H.M., Grondin, G.Y., Wei, F., Chung, F.: Design for block shear of coped beams with a welded end connection. J. Struct. Eng. 137(8), 1398–1410 (2011)

Zhu, M.-C., Li, G.-Q.: Behavior of beam-to-column welded connections in steel structures after fire. Proc. Eng. 210, 551–556 (2017)

Funding

The first author would like to thank for the 2018 SAE summer scholarship from the faculty of Science and Engineering, Curtin University, Perth WA, Australia. The second author would like to thank for partial financial support from the Centre of Excellence in Mathematics, Commission on Higher Education, Thailand. The last author would like to thank the Australia research council for the financial support and WA Main Road for providing some data for the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The main idea of this paper was proposed by YHW and NK. DW prepared the manuscript initially and performed all the steps of the proofs in this research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wiwatanapataphee, D., Khajohnsaksumeth, N. & Wu, Y.H. Effect of beam joinery on bridge structural stability. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 225 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2158-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2158-5