Abstract

In this study, we model and theoretically analyze a free convective three-dimensional flow of an incompressible second-grade fluid through a highly porous medium bounded by an infinite vertical porous plate subjected to a constant suction. We assume the permeability of the medium to be periodic and the free stream velocity to be uniform. The assumption of either constant or time-dependent permeability of a porous medium leads to two-dimensional flows; however, the flow becomes three-dimensional due to variable permeability of the porous medium. We obtain analytic solutions for velocity field, pressure, skin friction components, temperature distribution, and discuss and graphically visualize effects of physical parameters emerging in the mathematical model of the physical phenomenon on these physical quantities. We note that the main flow velocity component decreases due to enhancement in non-Newtonian parameter; however, the pressure rises due to thickening of the fluid.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the recent years, natural convection flows through a porous medium, which are quite prevalent in nature, have attracted the attention of many workers due to their many scientific and engineering applications. For example, in the field of chemical engineering for purification and filtration processes, in agriculture engineering to study seepage of water in river beds, the underground water resources, etc. In view of such important applications, Stuart [1] investigated a two-dimensional flow past a porous infinite plate subjected to constant suction in the presence of periodic free stream velocity, Soundalgekar [2] analyzed a free convective flow past a vertical oscillatory plate, Varshney [3] presented a fluctuating flow of a viscous fluid through a porous medium bounded by a porous plate, Raptis [4] described an unsteady free convective flow of a viscous fluid through a porous medium, and Raptis and Perdikis [5] examined a free convective oscillatory flow of a viscous fluid through a porous medium.

The permeability of the porous medium of all the studies stated has been assumed to be constant. A porous medium, however, containing fluid is an inhomogeneous medium, and therefore there can be various inhomogeneities existing in a porous medium. Therefore the permeability of the porous medium may not unavoidably be constant. Singh and Kumar [6] studied an unsteady two-dimensional free convective flow through a porous medium bounded by vertical porous infinite plate considering the permeability of the medium fluctuating in time about a constant mean.

Most of the workers have limited their studies to the two-dimensional flows only by considering the permeability of the porous medium either constant or time-dependent. Nevertheless, there may occur situations where the flow fields may be essentially three-dimensional, for instance, when the permeability distribution varies transversely to the potential flow. Many workers [7, 8] have studied the effects of such a transverse permeability distribution on the flow of an incompressible viscous fluid through a porous medium. Further, Singh and Sharma [9] analyzed a three-dimensional free convective flow through a porous medium with periodic permeability and heat transfer effect, Jain et al. [10] presented the influence of periodic permeability and temperature of a free convective three-dimensional flow of a viscous fluid through porous medium in the presence of slip. Recently, Reddy et al. [11] have explored the free convective magnetohydrodynamic three-dimensional flow through a highly porous medium with periodic permeability. They noted that the velocity of the fluid reduces due to heat sink and magnetic field. On the contrary, the heat transfer coefficient increases in the presence of heat absorption parameter.

All studies mentioned have been scrutinized for Newtonian fluids. Although the Navier–Stokes equations can manage the flows of Newtonian fluids, such equations are inadequate to describe the properties of non-Newtonian fluids. Various workers [12,13,14,15,16] analyzed viscoelastic fluids through porous medium/in a vertical channel/over a stretching sheet under different physical conditions.

The aim of the present study is to explore a three-dimensional free convective flow of a second-grade fluid through highly porous medium subjected to periodic permeability and its impact on the heat transfer rate. A second-grade fluid is the simplest non-Newtonian differential type fluid model possessing the normal stress difference phenomenon (non-Newtonian phenomenon). To the best of our knowledge, no attempt is made to explore the free convective three-dimensional flow of a second grade through highly porous medium when permeability of the medium varies periodically. In view of these facts, the main aim of our study is to explore such a problem. To achieve this goal, the layout of this work is as follows. Section 2 presents the problem description, whereas Sect. 3 describes the modeling of the problem. Section 4 investigates the model in two and three dimensions for the solutions of a secondary flow, energy equation, and main flow by perturbation technique. At the end of this section, friction coefficients along the x- and z-directions have been computed, and the coefficient of the rate of heat transfer has also been given. Section 5 incorporates results and discussion for the characteristics of the problem, whereas Sect. 6 briefs conclusions.

2 Problem description

In this paper, we investigate a three-dimensional incompressible second-grade fluid through a highly porous medium with constant suction bounded by an infinite porous plate. The plate lying vertically on the xz-plane with x-axis is taken along the plate in upward direction, and the normal to the plane of the plate is taken along the y-axis. A three-dimensional fluid has a laminar flow with uniform free stream velocity U. The porous medium has a variable permeability of the form

where \(K_{0}\) is the mean permeability of the medium, l is the wave length of the permeability of the distribution, and ε (≪1) is the amplitude of the permeability variation. Such a permeability variation shows that the problem is three-dimensional. All the fluid properties are supposed to be constant; however, the effect of the density variation with temperature is considered in the body-force term. The velocity field is

where u, v, w are the velocity components in the x-, y-, z-directions, respectively. All the physical quantities will be independent of x because of the infinite length of the plate in the x-direction; of course, the flow remains three-dimensional due to variation of periodic permeability (Fig. 1).

3 Modeling the problem

We have the following continuity, momentum, and energy equations, respectively, governing the fluid flow described in Sect. 2 [17, 18]:

where ρ is the density of the fluid, \(\varrho =c_{p}T\), \(\vec{q}=-k _{t}\nabla T\), T is the temperature, \(c_{p}\) is the specific heat at constant pressure, ∇ is the vector operator, \(k_{t}\) is the thermal conductivity, and τ̃ is the Cauchy stress tensor for second-grade fluid defined in [19] as

where \(\alpha _{1}\) and \(\alpha _{2}\) are material constants, Ĩ is the identity tensor, μ is the dynamic viscosity, p is the pressure, \(\tilde{A}_{1}\) and \(\tilde{A}_{2}\) are the Rivlin–Ericksen tensors defined as

For the model to be compatible with (3.4) and the thermodynamics in the sense that all motions meet the Clausius–Duhem inequality and assumption that the specific Helmholtz free energy is a minimum in equilibrium [19], we assume that

and

The appropriate boundary conditions [9, 11, 20] are

where \(V_{0}>0\) is the suction velocity, which is constant, and the negative sign occurs due to suction toward plate, \(p_{\infty }\) is a constant pressure in a free stream, and the temperature of the plate and the fluid temperature far away from the plate are \(T_{w}\) and \(T_{\infty }\), respectively. We define the following dimensionless variables:

where \(y^{\triangleright }\), \(z^{\triangleright }\), \(u^{\triangleright }\), \(v ^{\triangleright }\), \(w^{\triangleright }\), \(p^{\triangleright }\), \(K^{\triangleright }_{0}\), and \(\theta^{\triangleright } \) are nondimensional variables. Then Eqs. (3.8)–(3.12) and the boundary conditions (3.13) have the following form after the omission of the symbol “▷” for convenience:

subject to the boundary conditions

where the nondimensional parameters (Grashof number, Reynolds number, elastic parameter, suction parameter, and Prandtl number) are:

4 Investigation of the mathematical model

For the solution of Eqs. (3.15)–(3.19), we assume that in a neighborhood of the medium,

where ε is a very small parameter, and g stands for any of variables u, v, w, p, and θ.

4.1 Model in two dimensions

For \(\epsilon =0\), the problem transfers into two dimensions, so we have

subject to boundary conditions

The order of differential equation is increased from 2 to 3 due to the presence of an elasticity parameter. We are required three boundary conditions for a unique solution of Eqs. (4.3) and (4.5). To remove this difficulty, we assume the solution to be of the form

where L is a very small parameter. Solving Eqs. (4.2) and (4.4)–(4.6), we get the following solutions:

Using Eq. (4.8) in Eq. (4.3) and comparing the coefficients of \(O(L^{0})\) and \(O(L) \), we get the following boundary value problems:

Solving the boundary value problems (4.10)–(4.11), in view of Eq. (4.8), we get

The results of [9] are retrieved for \(L=0\).

4.2 Model in three dimensions

When \(\epsilon \neq 0\), the flow becomes three-dimensional, and the solution of the resulting problem can be obtained by taking a solution of the form given in Eq. (4.1). Then following partial differential equations are obtained from Eqs. (3.15)–(3.19) by comparing the first-order terms of ε:

Similarly, the boundary conditions (3.20) yield

The set of linear partial differential equations (PDEs) (4.13)–(4.18) describe the free convective three-dimensional flow.

4.3 Secondary flow solution

For the solution of PDEs (4.13)–(4.17), we first consider Eqs. (4.13), (4.15), and (4.16) being independent of the main flow and temperature field.

Assume that the solutions \(v_{1}\), \(w_{1}\), and \(p_{1}\) are of the forms

where \(v_{11}(y)\) has the derivative \(v_{11}'(y)\) with respect to y. The expressions in (4.19) satisfy the equation of continuity (4.13). Substituting Eqs. (4.19) into Eqs. (4.15) and (4.16), we have

subject to the boundary conditions

On solving both Eqs. (4.20) and (4.21) simultaneously to eliminate the pressure \(p_{11}\), we get the following differential equation:

Equation (4.23) can be solved by the method of perturbation. Assume that

where L is a very small parameter. Substituting Eq. (4.24) into Eq. (4.23) and boundary conditions (4.22) and then solving the resulting equations, we get

In view of (4.1), (4.9), and (4.19), we finally get

4.4 Pressure and temperature field

Using Eqs. (4.1), (4.9), (4.19), (4.21), and (4.26), we can obtain the value of pressure given by

To find an expression for the temperature distribution, we take

Then the PDE (4.17) subject to the boundary conditions

yields

where \(A=\frac{\lambda _{1}}{\pi R_{e}\mathit{Pr}}\), \(B=\frac{\pi }{\lambda ^{2}_{1}+R_{e}\mathit{Pr}\lambda _{1}-\pi ^{2}} \), \(\lambda _{1}=\frac{R_{e}}{2}+\sqrt{(\frac{R _{e}}{2})^{2}+\pi ^{2}+\frac{1}{K_{0}}}\), \(\lambda =\frac{R_{e}}{2}+\sqrt{(\frac{R_{e}}{2})^{2}+\frac{1}{K _{0}}}\), \(\lambda _{0}=\frac{R^{2}_{e}}{R^{2}_{e}\mathit{Pr}(\mathit{Pr}-1)-\frac{1}{K _{0}}}\), \(\beta =\frac{R_{e}\mathit{Pr}}{2}+\sqrt{(\frac{R_{e}\mathit{Pr}}{2})^{2}+ \pi ^{2}}\).

4.5 Main flow solution

The main flow velocity can be obtained from the PDE (4.14). Similarly to the previous sections, we assume that

as solution of (4.14) and

After huge calculations, we get

Equations (4.34) and (4.35) in view of Eqs. (4.33), (4.32), and (4.1) give the final main flow solution. It is worth mentioning that the results of [9] are recovered for \(L=0\). The constants involved in solutions (4.34) and (4.35) are as follows:

4.6 Skin friction coefficients

After getting the velocity field, the important physical quantities such as the skin friction component can be computed. The nondimensional skin friction component along the x-direction is as follows:

Omitting the sign of “▷” for convenience, we get the following result:

where

and

Similarly, the skin friction component in the nondimensional form along the z-direction is

where

4.7 Heat flux

The Nusselt number Nu can be obtained from the rate of heat transfer coefficient of temperature field given by

Nondimensioning and simplifying the resulting equation, we get

where

and

5 Results and discussion

In this work, a three-dimensional steady flow of a second-grade fluid through a porous medium with periodic permeability and heat transfer is modeled and analyzed theoretically. Analytical solutions for the velocity field, skin friction, pressure, and heat flux are obtained using the regular perturbation method. The effects of nondimensional parameters, such as the Reynolds number \(R_{e}\), Prandtl number Pr, elastic parameter L, permeability parameter \(K_{0}\), and Grashof number G, on these physical quantities are visualized graphically.

Figure 2 displays the effect of the Reynolds number on the velocity field, pressure, and temperature distribution when all other nondimensional parameters are fixed (\(\mathit{Pr}=7\), \(K_{0}=1\), \(G=1\), \(z=0\), \(L=0.01\), \(\varepsilon =0.01\)) and the Reynolds number is varied: \(R_{e}=1,3,5\). It is observed that with the increase of the Reynolds number, the main flow velocity component u (Fig. 2(a)) also increases and reaches its maximum value at the boundary for each value of the Reynolds number taken in this regard. Moreover, the boundary layer thickness decreases with an increase in Reynolds number. Similarly, the magnitude of the velocity component v (Fig. 2(b)) increases with an increase in Reynolds number. On the other hand, it is noted that the magnitude of this velocity component decreases as we move away from the plate, which seems physically correct, because it is well established that the suction effect on the flow is maximum near the plate. It is observed from Fig. 2(c) that for a fixed value of \(R_{e}\), the velocity component w increases exponentially near the plate, attains its maximum value, then decreases rapidly, and finally converges to zero as \(y\rightarrow \infty \). A parabolic profile near the plate is obtained. It is also noted that this velocity component increases with an increase in Reynolds number \(R_{e}\). Physically, this means that the effect of inertial forces is dominant over viscous forces near the plate. The pressure also increases with an increase in Reynolds number \(R_{e}\) near the plate (Fig. 2(d)). Its value is maximum at the free surface. Figure 2(e) demonstrates the effect of Reynolds number \(R_{e}\) on the temperature distribution. It shows that the thermal boundary layer decreases with an increase in Reynolds number \(R_{e}\).

Figure 3 illustrates the effect of permeability parameter \(K_{0}\) on the velocity components, pressure, and temperature distribution when all other nondimensional parameters are fixed (\(\mathit{Pr}=7\), \(R_{e}=1\), \(G=1\), \(z=0\), \(L=0.01\), \(\varepsilon =0.01\)) and permeability parameter varies: \(K_{0}=0.1,0.5,1\). It is detected that the main flow velocity component u (Fig. 3(a)) decreases with an increase in permeability parameter \(K_{0}\). The minimum and maximum values of the velocity component occur at the boundaries. A similar effect of permeability parameter \(K_{0}\) on the velocity component v is perceived from Fig. 3(b). It is witnessed from Fig. 3(c) that, for a fix value of \(K_{0}\), the velocity component w increases exponentially near the plate, attains its maximum value, then decreases rapidly, and finally converges to zero as \(y\rightarrow \infty \). A parabolic profile near the plate is obtained. It is also noted that this velocity component decreases with an increase in \(K_{0}\). On the contrary, the pressure increases with an increase in permeability parameter \(K_{0}\) near the plate (Fig. 3(d)). Its value is maximum at the free surface. Figure 3(e) demonstrates the effect of permeability parameter \(K_{0}\) on the temperature distribution. A weak dependence of the temperature distribution upon permeability parameter \(K_{0}\) is noted.

Figure 4 shows the effect of the Prandtl number on the main flow velocity component u and temperature field. This figure reveals that an increase in Prandtl number causes a decrease in the velocity component. It is evident from this figure that the temperature of the fluid decreases with an increase in Prandtl number Pr causing reduction in thermal boundary layer thickness. In fact, at high Prandtl number, the fluid has a low thermal conductivity resulting in reduction in thermal layer thickness. Therefore, this observation quite agrees with the physical situation that the boundary layer thickness decreases with an increase in Prandtl number.

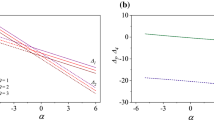

Figure 5 exhibits the effect of the non-Newtonian parameter L on the main flow velocity component u and pressure P. It is perceived that an increase in the non-Newtonian parameter leads to a decrease in the velocity component, which seems physically correct because an increase in the non-Newtonian parameter causes fluid thickening resulting in reduction in the velocity. The increase in non-Newtonian parameter also leads to a decrease in pressure due to thickening of the fluid.

Figure 6 displays the effect of the Grashof number (free convection parameter) on the main flow velocity component u for cooling of the plate. It is obvious from this Figure that the velocity component increases due to greater cooling of the channel, that is, as the Grashof number G increases.

In Fig. 7, the nondimensional skin friction component along the main flow direction is plotted against the Reynolds number for different values of elastic parameter L, permeability parameter \(K_{0}\), Grashof number G, and Prandtl number Pr. The skin friction exerted by the plate on the fluid increases with an increase in Reynolds number in all cases. For small values of elastic parameter L (<0.1), the skin friction component tends to zero, which physically means that the effect of inertial and viscous forces balance each other, resulting in zero effect of the skin friction component along the x-axis. It, however, increases by increasing the elastic parameter L (Fig. 7(a)). Figure 7(b) shows that the skin friction component decreases with an increase in permeability parameter \(K_{0}\). Depending upon the value of permeability parameter \(K_{0}\), for small values of the Reynolds number \(R_{e}\), the skin friction is exerted by the fluid on the plate, and, of course, the behavior is reversed for large values of \(R_{e}\). A similar effect of the Grashof number G on the skin friction is noted (Fig. 7(c)). On the contrary, an increase in the Prandtl number boosts the skin friction (Fig. 7(d)). The numerical values of the skin friction component with the variation of nondimensional parameters are also presented in Table 1.

Figure 8 is plotted for the nondimensional skin friction component along the z-direction versus the Reynolds number for different values of the elastic parameter L and permeability parameter \(K_{0}\). It is observed that an increase in \(R_{e}\) leads to an increase in the skin friction component in both cases. It is also noted that the skin friction exerted by the fluid on the plate enhances by increasing the elastic parameter. However, an opposite trend is noted for the permeability parameter. The numerical values in Table 2 are clearly the evidence of Figs. 8(a) and 8(b).

In Fig. 9 the variation of the nondimensional heat transfer coefficient is plotted against the Reynolds number for different values of the Prandtl number and permeability number. It is witnessed that an increase in Reynolds number enhances the heat transfer coefficient. In contrast, an increase in either the Prandtl number or the permeability number leads to a decrease of the heat transfer coefficient.

6 Final remarks

The present analysis aims to present approximate solutions for the three-dimensional free convective flow of a second-grade fluid through a porous medium with periodic permeability in the presence of heat transfer. Analytic solutions for the velocity field, skin friction components, and temperature distribution using regular perturbation are obtained and analyzed theoretically. The main findings of this study are as follows.

-

The Reynolds number provides a mechanism to control the skin friction along the x-axis and along the z-axis.

-

The permeability is an economical parameter to reduce the pressure causing reduction in energy consumption.

-

The permeability is a tool to minimize the skin friction components (Tables 1 and 2).

-

The non-Newtonian parameter causes a reduction of the main flow velocity component. However, it enhances the pressure due to thickening of the fluid.

-

The main flow velocity component increases due to high cool of the channel.

-

A weak dependence of the temperature field on the permeability parameter is noted.

-

The results of [9] are recovered in the absence of the non-Newtonian parameter L.

Abbreviations

- \(\tilde{A_{1}}\), \(\tilde{A_{2}}\) :

-

Rivlin–Ericksen tensors

- \(A_{i}\); \(i=1,2,3,4\) :

-

constants

- \(c_{p}\) :

-

specific heat at constant pressure (J/K⋅kg)

- \(C_{i}\); \(i=1,2,\ldots,10\) :

-

constants of integration

- D, E, F, H, I, J, M, N, O, P :

-

constants of integration

- g :

-

gravity (m/s2)

- G :

-

Grashof number

- Ĩ :

-

unit tensor

- \(k_{t}\) :

-

thermal conductivity (watts per meter-Kelvin: W/(m⋅K))

- \(K_{0}\) :

-

mean permeability (m2)

- l :

-

wave length (m)

- L :

-

elastic parameter

- Nu :

-

Nusselt number

- p and \(p_{\infty }\) :

-

pressure and constant pressure (\(\mathrm{Pa=N/m}^{2}\))

- Pr :

-

Prandtl number

- q⃗ :

-

heat flux (kg/s3)

- \(R_{e}\) :

-

Reynolds number

- T :

-

temperature (Kelvin = K)

- \(T_{w}\); \(T_{\infty }\) :

-

boundary temperature; free stream temperature (K)

- u, v, w :

-

components of velocity (m/s)

- U; \(V_{0}\) :

-

uniform free stream velocity; constant suction velocity (m/s)

- V⃗ :

-

velocity field (m/s)

- x, y, z :

-

coordinate axes (m)

- α :

-

suction parameter

- \(\alpha _{1}\), \(\alpha _{2}\) :

-

material constants

- β :

-

coefficient of thermal expansion (1/K)

- ϵ :

-

amplitude of permeability variation (m)

- μ; ν :

-

dynamic viscosity (kg/(m⋅s)); kinematic viscosity (m2/s)

- ρ :

-

density (kg/m3)

- ϱ :

-

internal energy per unit mass (J/kg)

- τ̃ :

-

Cauchy stress tensor (N/m2)

- \(\tau _{x}\) :

-

skin friction component along the x-direction (N/m2)

- \(\tau _{z}\) :

-

skin friction component along the z-direction (N/m2)

- ∇:

-

vector operator (1/m)

References

Stuart, J.T.: Two-dimensional flow past an infinite porous plate with constant suction and periodic free stream. Proc. R. Soc. A 231, 116 (1955)

Soundalgekar, V.M.: Free convection effects on the flow past a vertical oscillatory plate. Astrophys. Space Sci. 64, 165–172 (1979)

Varshney, C.L.: Fluctuating flow of viscous fluid through a porous medium bounded by a porous plate. Indian J. Pure Appl. Math. 10(12), 1558–1564 (1979)

Raptis, A.A.: Unsteady free convective flow through a porous medium. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 21(4), 345–348 (1983)

Raptis, A.A., Perdikis, C.P.: Oscillatory flow through a porous medium by the presence of free convective flow. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 23, 51–55 (1985)

Singh, K.D., Kumar, S.: Two-dimensional unsteady free convective flow through a porous medium bounded by an infinite vertical porous plate with periodic permeability. J. Math. Phys. Sci. 27, 141–148 (1993)

Singh, K.D., Chand, K., Verma, G.N.: Heat transfer in a three dimensional flow through a porous medium with periodic permeability. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 75, 950–952 (1995)

Singh, K.D., Verma, G.N.: Three dimensional oscillatory flow through a porous medium with periodic permeability. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 75, 599–604 (1995)

Singh, K.D., Sharma, R.: Three dimensional free convective flow and heat transfer through a porous medium with periodic permeability. Indian J. Pure Appl. Math. 33(6), 941–949 (2002)

Jain, N.C., Sharma, B., Vijay, D.K.: Three dimensional free convective flow heat transfer flow through a porous medium with periodic permeability in slip flow regime. J. Energy Heat Mass Transf. 28(1), 29–44 (2006)

Reddy, P.R., Srihari, K., Reddy, S.R.: Combined heat and mass transfer in MHD three-dimensional porous flow with periodic permeability & heat absorption. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 3(2), 573–593 (2012)

Mishra, S.R., Dash, G.C., Acharya, M.: Mass and heat transfer effect on MHD flow of a visco-elastic fluid through porous medium with oscillatory suction and heat source. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 57(2), 433–438 (2013)

Acharya, A.K., Dash, G.C., Mishra, S.R.: Free convective flow of visco-elastic fluid in a vertical channel with Dufour effect. World Appl. Sci. J. 28(9), 1275–1280 (2013)

Baag, S., Acharya, M.R., Dash, G.C., Mishra, S.R.: MHD flow of a visco-elastic fluid through a porous medium between infinite parallel plates with time dependent suction. J. Hydrodyn. 27(5), 840–847 (2015)

Mishra, S.R., Pattnaik, P.K., Bhatti, M.M., Abbas, T.: Analysis of heat and mass transfer with MHD and chemical reaction effects on viscoelastic fluid over a stretching sheet. Indian J. Phys. 91(10), 1219–1227 (2017)

Mishra, S.R., Tripathy, R.S., Dash, G.C.: MHD viscoelastic fluid flow through porous medium over a stretching sheet in the presence of non-uniform heat source/sink. Rend. Circ. Mat. Palermo Ser. 2 67(1), 129–143 (2018)

Chhabra, R.P., Richardson, J.F.: Non-Newtonian Flow and Applied Rheology: Engineering Applications, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2008)

Irgens, F.: Rheology and Non-Newtonian Fluids. Springer, Switzerland (2014)

Dunn, J.E., Fosdick, R.L.: Thermodynamics, stability, and boundedness of fluids of complexity 2 and fluids of second grade. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 56, 191 (1974)

Choudhury, R., Dey, D.: Free convective visco-elastic flow with heat and mass transfer through a porous medium with periodic permeability. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 53, 1666–1672 (2010)

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments to enrich the quality of manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this paper as no database was generated or analyzed during the contact study.

Authors’ information

M.A. Rana is Professor in Department of Mathematics & Statistics, Riphah International University, Sector I-14, Islamabad, Pakistan. A. Latif is Ph.D. scholar in Department of Mathematics & Statistics, Riphah International University, Sector I-14, Islamabad, Pakistan, and lecturer in Department of Mathematics, GC University Faisalabad, Pakistan.

Funding

No institute or company supported this paper financially. However, the authors themselves are the funding source, and this research is technically supported by Riphah International University, Islamabad, Pakistan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The first author originated the idea of the problem and physics of effect of nondimensional parameters, whereas the corresponding author developed the mathematical model, solved the problem, and wrote the manuscript thoroughly. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Both authors have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rana, M.A., Latif, A. Three-dimensional free convective flow of a second-grade fluid through a porous medium with periodic permeability and heat transfer. Bound Value Probl 2019, 44 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-019-1144-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-019-1144-x