Abstract

The problem in this paper is motivated by physical problems concerned with the case when a class of continuous and equimeasurable densities of a string is given then how to find minimal frequencies among these given densities, that is, what kind of densities minimize the frequencies. By taking Dirichlet eigenvalues into account, given a certain weight function ω, we will show the minimizer of the mth eigenvalue is the m-degree continuous symmetrical decreasing rearrangement of ω. The main result of this paper can be viewed as complementary to Schwarz’s work (Schwarz in J. Math. Mech. 10:401–422, 1961).

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

For a string with the density of mass \(\omega(x)\) the spatial oscillation of the string with fixed ends is described by the weighted eigenvalue problem

Here τ is the spectral parameter. Problem (1)–(2) is called a weighted eigenvalue problem in some literature and ω is called a weight function. See [2–6]. The classical Sturm–Liouville theory has given the complete structure of the eigenvalues of (1)–(2) as

see [7]. The purpose of this paper is to consider the following problem.

Let function \(\omega(x)\) be continuous in \(x\in[0,1]\) with \(0\le \omega(x) \le1\), and satisfy

with \(\omega(x)>0\) almost everywhere in I. Throughout this paper we suppose

Here \(\mu(\cdot)\) stands for the Lebesgue measure. A function \(\Omega (x)\) is said to be equimeasurable to \(\omega(x)\) on I, if

see, for example [8]. The problem we are concerned with is to determine which function that equimeasurable to \(\omega(x)\) and such that \(\tau_{m}(\omega)\) takes minimum value in this equimeasurable class.

The physical explanation of this problem is as follows. Given a class of continuous densities with the same distribution, what kind of density minimizes the frequencies of a string with fixed ends? The solution to this problem will be called a minimizer in this paper. The problem is called a minimization problem; it dates back to Courant and Krein [3, 9].

In page 463 [9], the authors left the reader an exercise: “The fundamental tone of a stretched string of given uniform tension along which a given mass has been distributed is lowest when the entire mass is concentrated at the midpoint”. In mathematical words, among positive weight functions with the same integral value, the generalized function

also known as a Dirac measure, minimizes the first eigenvalue \(\tau_{1}\). Krein [3] determined minimizers among the following admissible set of functions:

where h, H, r are given. The main result of [3] is that the unique minimizer that minimizes \(\tau_{m}\) is a periodic step function with period \(1/m\) taking only values h and H. Moreover, the minimizer of the mth eigenvalue is symmetrical decreasing in each periodic interval \([\frac{k-1}{m},\frac{k}{m}]\), \(k=1,2,\ldots, m\).

The results have many generalizations; see for example [2, 4, 10, 11]. In recent papers [6, 11–15] the authors generalized Krein’s result for various kinds of differential operators from second order linear differential operators or nonlinear p-Laplacian to measure differential equations. The admissible set of functions varies from integrable potentials or weights to measures with the same integral value or with fixed variations. All in all the admissible set of functions in these minimization problems are either discontinuous or integrable functions, while the results of these papers show that minimizers of eigenvalues are symmetric.

When an admissible set of functions in minimization problem is given as continuous equimeasurable functions, the problem has been addressed in some of the literature. The best result we know is Schwarz’s work [1]. Here the author considered ω in (1) to be “piecewise continuous” positive functions. (A function with at most a finite number of discontinuous point is called piecewise continuous.) The result in [1] is that, for any \(m\ge1\),

Moreover, equality in (5) holds if and only if \(\omega =\omega^{+} _{m}\). Here \(\omega^{+}_{m}\) is the m-degree symmetrical decreasing rearrangement of ω; see definition (6) and (7) below.

Since ω is assumed “piecewise continuous”, \(\omega^{+}_{m}\) may also be piecewise continuous. But, in the case of a physical application, to determine minimizers over continuous functions is more meaningful, just as Schwarz wrote in his paper “While for physical application this theorem is of interest only for positive continuous functions, our method of proof forces us to consider equimeasurable classes of piecewise continuous functions”.

It seems that to determine minimizers over an admissible set of “bad continuous” functions is easier than “good continuous” functions. In this paper we point out \(\omega^{+}_{m}\) is continuous, provided ω satisfies (3) and (4). Our main theorem is the following one.

Theorem 1.1

Given \(m\in \mathbb{N}\), suppose \(\omega(x)\) satisfies (3) and (4). Then \(\omega^{+}_{m}(x)\) is continuous and such that (5) holds.

The result is meaningful in practical science. For instance, in a remarkable paper [5], after having solved a minimization problem associated with (1) where an admissible set of functions is a certain class of integrable functions, the authors gave an explanation of its application to spatial biological cases. The weight function ω represents a bio density or a density of resources. To determine the minimizer of the eigenvalue will be helpful in optimizing resources and to maintain the existence of species.

2 Proof of main theorem

2.1 Preliminaries

Let us give some preliminaries on level sets, distributions and m-degree symmetrical decreasing rearrangement of functions.

Lat there be given a general bounded measurable function \(f(x)\), \(x\in J=[a,b]\). For any \(t\in \mathbb{R}\), the level set of f is denoted by

see [8]. Associated with level sets, one has the distribution function

One sees that \(D_{f,J}(t)\) is non-increasing with \(D_{f,J}(\sup_{J} f)=0\) and \(D_{f,J}(\inf_{J} f)=\mu(J)\).

The symmetric rearrangement, or the Schwarz rearrangement [16] is a method used by Hardy, Littlewood and Polya in [16] to study the Hardy–Littlewood–Polya inequality Also it is useful in many mathematical and physical problems. The following is standard; see for example,[1, 8, 16, 17].

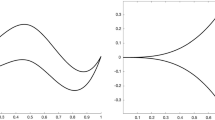

Let \(f\ge0\). By using a distribution function of f, the function

is called a symmetrical decreasing rearrangement (SDR) of f, because it is increasing in \([a,\frac{a+b}{2}]\) and decreasing on \([ \frac{a+b}{2},b]\). See [8, 17].

Now let us introduce m-degree SDR. For any fixed positive integer m, define an m period function by

and

One sees \(f^{+}_{m}\) has m periods in J with period \(\frac{b-a}{m}\), we call each interval \([a+\frac{(j-1)(b-a)}{m},a+ \frac{j(b-a)}{m}]\) a periodic interval of \(f^{+}_{m}\). Such a function \(f^{+}_{m}\) is called m-degree SDR of \(f(x)\) on J. Some properties for \(f^{+}_{m}\) are as follows.

- (\(\mathbf{p}_{1}\)):

-

For any \(t\ge0\), one has equimeasurability,

$$\mu\bigl\{ x\in J: f(x)\ge t\bigr\} =\mu\bigl\{ x\in J: f^{+}_{m}(x) \ge t\bigr\} . $$ - (\(\mathbf{p}_{2}\)):

-

For each \(j=1,\ldots,m\),

$$f^{+}_{m}(x)\equiv f^{+}_{m}\biggl(2a+ \frac{(2j-1)(b-a)}{m}-x\biggr),\quad \forall x\in\biggl[a+\frac{(j-1)(b-a)}{m},a+ \frac{j(b-a)}{m}\biggr]. $$Moreover, \(f^{+}_{m}(x)\) is symmetrical decreasing on each periodic interval. In particular, if a nonnegative measurable function \(f(x)\) satisfies (7) and also symmetrical decreasing on each periodic interval, then \(f^{+}_{m}(x)=f(x)\) a.e. \(x\in[a,b]\).

- (\(\mathbf{p}_{3}\)):

-

If \(0\le f(x)\le M\) a.e. \(x\in[a,b]\) for some \(M>0\), then \(0\le f^{+}_{m}(x)\le M\) a.e. \(x\in[a,b]\). Moreover,

$$f^{+}_{m}\biggl(a+\frac{(j-1)(b-a)}{m}\biggr)=f^{+}_{m} \biggl(a+\frac{j(b-a)}{m}\biggr) = \inf_{J} f(x), $$and

$$f^{+}_{m}\biggl(a+\frac{(2j-1)(b-a)}{2m}\biggr)=\sup _{J} f(x). $$

2.2 Proof of Theorem 1.1

The proof of Theorem 1.1 is based on the following lemma.

Lemma 2.1

Let f be positive measurable, then distribution function \(D_{f,J}(t)\) is continuous if and only if (4) holds for f. Furthermore, if in addition

then \(D_{f,J}(t)\) is strictly decreasing in \(t\in[\inf_{J} f(x), \sup_{J} f(x)]\).

Proof

The first conclusion is standard and can be found for example in [17]. Now we are going to show \(D_{f}(t)\) is strictly decreasing in \(t\in[\inf_{J} f(x), \sup_{J} f(x)]\). Take \(t,s\in[ \inf_{J} f(x), \sup_{J} f(x)]\) with \(s< t\). Then

By (4) we have

This completes the proof. □

Proof of Theorem 1.1

Since open sets must have a positive measure, the conclusion of Lemma 2.1 must be true for a continuous function which satisfies (4). Therefore, we have from hypotheses (3) and (4) on \(\omega(x)\) that the distribution \(D_{\omega,I}(t)\), \(t\in[0,1]\) is continuous and strictly decreasing. Then

is continuous. Therefore, \(\omega^{+}_{m}(x)\) is also continuous on I. Finally, by using Schwarz’s result, we see that (5) holds for our ω. □

References

Schwarz, B.: On the extrema of the frequencies of nonhomogeneous strings with equimeasurable density. J. Math. Mech. 10, 401–422 (1961)

Barnes, D.: Rearrangement of functions and lower bounds for eigenvalues of differential equations. Appl. Anal. 13, 237–248 (1982)

Krein, M.G.: On certain problems on the maximum and minimum of characteristic values and on the Lyapunov zones of stability. Transl. Am. Math. Soc. (2) 2(1), 163–187 (1955)

Karaa, S.: Sharp estimates for the eigenvalues of some differential equations. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 29, 1279–1300 (1998)

Lou, Y., Yanagida, E.: Minimization of the principle eigenvalue for an elliptic boundary value problem with indefinite weight and applications to population dynamics. Jpn. J. Ind. Appl. Math. 23, 275–292 (2006)

Yan, P., Zhang, M.: Continuity in weak topology and extremal problems of eigenvalues of the p-Laplacian. Trans. Am. Math. Soc. 363, 2003–2028 (2011)

Zettl, A.: Sturm–Liouville Theory. Am. Math. Soc., Providence (2005)

Lieb, E., Loss, M.: Analysis. Am. Math. Soc., Providence (1997)

Courant, R., Hilbert, D.: Methods of Mathematical Physics. Wiley, New York (1953)

Meng, G.: Minimization of eigenvalues for some differential equations with integrable potentials. Bound. Value Probl. 2013, 220 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1687-2770-2013-220

Payne, L.E.: Isoperimetric inequalities and their applications. SIAM Rev. 9, 453–488 (1967)

Wei, Q., Meng, G., Zhang, M.: Extremal values of eigenvalues of Sturm–Liouville operators with potentials in \(L^{1}\) balls. J. Differ. Equ. 247, 364–400 (2009)

Yan, P., Zhang, M.: Best estimates of weighted eigenvalues of one-dimensional p-Laplacian. Northeast. Math. J. 19, 39–50 (2003)

Yan, P., Zhang, M.: A survey on extremal problems of eigenvalues. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012, Article ID 670463 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/670463

Zhang, M.: Extremal eigenvalues of measure differential equations with fixed variation. Sci. China Math. 53(10), 2573–2588 (2010)

Hardy, G.H., Littlewood, J.E., Polya, G.: Inequalities. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1934)

Talenti, G.: Best constant in Sobolev inequality. Ann. Mat. Pura Appl. 4, 353–372 (1976)

Acknowledgements

Both authors would like to thank professor Meng Gang and Meirong Zhang for helpful discussions.

Funding

Both authors are supported by scientific starting research foundation of Inner Mongolia University, No. 21200-5175108 and No. 20100-5165106.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors have equally contributed to this article and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, Z., Zhou, L. Continuous minimizer of eigenvalues for eigenvalue problem with equimeasurable weights. Bound Value Probl 2018, 73 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-018-0991-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-018-0991-1