Abstract

Introduction

Diet during infancy and early childhood can have implications on child growth, health, and developmental trajectories. Yet, poor dietary habits are common in young children, who often consume diets that are not aligned with dietary recommendations. Early childhood education and care (ECEC) is a recommended setting to deliver healthy eating interventions as they offer existing infrastructure and access to a large number of children. This protocol aims to describe the methods of a systematic review to assess the effectiveness of healthy eating interventions conducted within the ECEC setting to improve child diet.

Methods and analysis

Eight electronic databases including Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Complete, PsycINFO, ERIC, SCOPUS, and SPORTDiscus will be searched from conception to March 2020. Randomised controlled trials (RCT) of dietary interventions targeting children aged up to 6 years conducted within the ECEC setting (including pre-schools, kindergartens, long day care, and family day care) will be included in the review. The primary review outcome is any measure of child dietary intake. Secondary outcomes include (i) child anthropometrics, (ii) child cognition, (iii) child mental health, (iv) child quality of life, (v) the absolute cost or cost-effectiveness of included interventions, and (vi) any reported adverse effects. Study inclusion, data extraction, and risk of bias assessments will be performed independently by two reviewers. Meta-analyses will be performed if adequate data is available, else review findings will be described narratively.

Discussion

This systematic review seeks to synthesise the effectiveness of healthy eating interventions conducted within the ECEC setting for improving child diet. This review will also seek to describe the effect of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions on a variety of important secondary outcomes (adverse events and cost-effectiveness) that will enhance the public health policy and practice relevance of review findings.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO [ID CRD42020153188]

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Poor dietary intake represents a major modifiable risk factor for chronic diseases including obesity, cardiovascular disease, and some cancers [1, 2]. In particular, low intake of fruits and vegetables, combined with a high intake of energy-dense, nutrient-poor, discretionary foods and beverages (high in salt, added sugars, and/or saturated fat) has been attributed to a range of chronic health conditions [3, 4]. The first years of life are a critical period for establishing good dietary habits, as they have been found to track into adulthood [2], and can influence child growth, general health, and developmental trajectories [5,6,7]. For example, unhealthy dietary intakes in children as young as 3 years of age have been found to influence cardiovascular disease markers, including obesity, dyslipidaemia, and high blood pressure, which can persist through to adulthood [8,9,10,11]. Despite this, international data indicates that in infants and young children, approximately 30% of total daily energy intake comes from discretionary (energy-dense, nutrient-poor) foods, and over 90% of this population are not consuming the recommended serves of vegetables [12, 13].

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) is increasingly acknowledged as a setting that can offer the foundations for lifelong child learning and development [14]. ECEC services are inclusive of regulated care services such as long day care, preschools, nurseries, kindergartens, occasional care, and family day care services that cater for children up to 6 years, prior to compulsory schooling [15]. In high-income countries such as Australia, Canada, the UK, Denmark, Norway, and Germany, approximately 80 to 90% of children aged under 5 years attend some form of ECEC, for an average of up to 30 h per week [16,17,18,19]. Given that ECEC services represent a captive setting, where children can consume up to two thirds of their recommended daily intake [20], it represents a promising avenue for targeting dietary behaviours in infants and young children [21,22,23].

The Determinants of Nutrition and Eating (DONE) framework (2.0) suggests that a range of factors can influence dietary choices [24]. Such determinants include food availability and accessibility, portion sizes, food beliefs and habits, the eating environment, and exposure to food promotion and marketing [24]. Thus, in most countries with regulated ECEC services, licensing and accreditation standards exist to support child wellbeing and healthy eating, by requiring ECEC services to implement practices and policies to support children to consume nutritious foods that help meet the social, cultural, and educational needs of the children [25, 26]. Additional standards related to ECEC nutrition policies, education, and role modelling for ECEC staff are also encouraged [25]. As such, ECEC is a recommended setting for influencing child diet due to its broad reach and available infrastructure to support the delivery of healthy eating interventions.

An umbrella review including 12 systematic reviews by Matwiejczyk and colleagues [27] indicated that most ECEC-based interventions seeking to improve children’s eating habits were typically found to improve at least one measured dietary component including food groups and/or nutrient intakes [27], further suggesting that the most impactful interventions were those focused on environmental changes such as menu modifications, policy, and changes to food provision coupled with technical support and training [27]. It must be highlighted however that these conclusions are based on systematic review searches conducted over 3 years ago and may not reflect updated intervention approaches and findings, given the continued policy and public health commitment to the sector [28, 29]. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review is to undertake an updated systematic literature search to evaluate the effectiveness of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions for improving child diet. This review will report additional relevant policy decision-making outcomes including cost-effectiveness and adverse effects of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions, which have not been previously reported on in other reviews [30].

Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review is:

-

To describe the effectiveness of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions for improving child dietary outcomes.

Secondary objectives of this systematic review are:

-

To describe the effectiveness of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions for improving measures of child weight status

-

To describe the effectiveness of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions for improving child cardiovascular disease risk markers

-

To describe the effectiveness of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions in improving child cognitive, mental health and quality of life outcomes

-

To describe the absolute cost or cost-effectiveness of the included interventions

-

To describe any adverse events or unintended effects related to included interventions

Methods and analysis

This article seeks to describe the methods of a systematic review and meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) [31]. The protocol is registered with PROSPERO the international prospective register for systematic reviews, ID CRD42020153188.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We will include only RCTs (including cluster-RCTs, stepped-wedge RCTs, factorial RCTs, multiple baseline RCTs, and randomised crossover trials). RCTs are considered the highest quality study design for establishing causality, as such we expect this will provide a more accurate estimation of the overall effect of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions.

We will only include cluster-RCTs with a minimum of two intervention sites and two control sites, as per the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) recommendations [32].

Types of participants

We will include interventions that seek to improve the dietary intake of children attending an ECEC service, conducted in any country internationally. A variety of participant groups may be included in such trials, including (but not limited to):

-

Children aged 6 years and under attending the ECEC service.

-

Parents, guardians, or carers of children attending the ECEC service.

-

Professionals responsible for the care provided to children attending the ECEC service, including ECEC service directors, educators, volunteers, cooks, or other employed staff.

-

Those responsible for the oversight and accreditation of ECEC services, including government authorities, or regulatory agencies, or those with the capacity to influence the nutritional practices of ECEC services, such as those involved in the food supply chain.

Studies targeting children with special needs or clinical conditions (e.g. those with a diagnosed disease or health condition) will be excluded.

Types of interventions

This review seeks to include ECEC-based healthy eating interventions conducted within the ECEC setting. This setting includes formal paid care such as preschools, nurseries, long day cares, and kindergartens, as well as family day cares (also known as family child care homes and childminding in which a small group of children is offered care within the educator’s home) that offer care for children up to 6 years, prior to compulsory schooling [33].

Included interventions must seek to influence child diet, but may also include other behavioural components including physical activity and sleep. Included interventions may be single-component or multi-component interventions (i.e. interventions that include more than one strategy to influence child diet). There will be no restriction on intervention duration. Interventions that target both the ECEC service and other settings, such as the home, will be included if the ECEC setting was the primary setting of the intervention.

Interventions that focus specifically on examining malnutrition/malnourishment will be excluded. Obesity management interventions (i.e. those that include only children with overweight or obesity) will also be excluded.

Control

We will include studies that report the outcomes of an intervention versus no intervention (control), delayed intervention (wait-list control), usual care, or an alternative intervention that does not seek to influence diet.

Types of outcomes

Primary outcomes

We will include any measure of child dietary intake. Such measures could include assessments of intake that occur during attendance at childcare or overall dietary intake. Dietary intake may be captured using objective methods including nutritional biomarkers such as doubly labelled water (measure of energy consumption), plate waste audits, or direct observations [34]. Child diet may also be evaluated using subjective methods (e.g. parent-reported dietary intake), such as short diet questions, food frequency questionnaires, food diaries, diet histories, and 24-h recalls. Measures of foods or beverages provided to children, for example, served or listed on childcare menus, but do not assess child intake, will be excluded. Measures of child dietary intake may include, but are not limited to:

-

Macronutrient intake (e.g. energy (kJ), fat (g), carbohydrate (g), protein (g), fibre (g)).

-

Food group intake (e.g. vegetables (g or serving)).

-

Intakes of specific dietary components of interest (e.g. sugar (g), or sugar-sweetened beverage (mL)).

-

Percent total energy contribution (e.g. percentage of total energy contributed from discretionary/snack foods).

-

Measures of overall diet quality (e.g. diet score measuring the consistency of dietary intakes to dietary guidelines).

Secondary outcomes

Measures of child weight status or anthropometric measures could be parent-reported, or measured by trained researchers, or ECEC staff. Specific anthropometric measures of interest include:

-

Absolute weight in kilograms (kg)

-

Body mass index (BMI)/zBMI score

-

Waist circumference (cm)

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

-

Ponderal index

-

Percent body fat

-

Skin-fold thickness

Measures of child cardiovascular disease risk markers may include:

-

Blood pressure (e.g. systolic blood pressure/diastolic blood pressure)

-

Blood lipids (e.g. total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, Apo B, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, Apo A-1)

-

Blood glucose (e.g. measure of blood glucose, glucose tolerance test, HbA1c)

Measures of child cognitive performance may include [35], but are not limited to:

-

Bayley Scale of Infant Development [36].

-

Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children [37].

-

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence [38].

-

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale [39].

-

Differential Abilities Scales [40].

-

The early years toolbox for assessing early executive function, language, self-regulation, and social development [41].

Measures of child mental health may include, but are not limited to:

-

The Child Behavioural Checklist (CBCL) [42].

Measures of child quality of life may include, but are not limited to:

-

The Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory [43].

Estimates of the intervention absolute cost or assessment of the intervention cost-effectiveness may include:

-

Cost-effectiveness ratio

-

Cost of the program per year of life saved

-

Cost of the intervention for each quality-adjusted life years (QALY) gained

Unintended adverse consequences of the interventions could be assessed using questionnaires, surveys, direct observations, or service audits, and may relate to:

-

Child health

-

Service operations

-

Staff/parent attitudes

Search methods for identification of studies

We will use a search strategy based on a previously conducted Cochrane review [44], adapted by a research librarian to suit our research question. The search was based on the following domains using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for ‘diet/nutrition’ and ‘ECEC’ and ‘randomised controlled trial’ and ‘humans’. Our search terms for each electronic database are outlined in Table S1 [see Additional file 1].

Electronic searches

A systematic search strategy will be undertaken from database conception until March 2020 using the following electronic databases:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trial (CENTRAL);

-

Ovid MEDLINE;

-

EMBASE;

-

CINAHL Complete;

-

PsycINFO;

-

ERIC;

-

SCOPUS;

-

SPORTDiscus.

We will not impose any language or time restrictions on the searches.

Unpublished or grey literature searches

In addition to electronic database searches, we will search for relevant unpublished or grey literature publications using the following:

-

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/intrp)

-

The registry ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinical.trials.gov)

-

Google Scholar (first 100 results)

Searching other resources

Additional searches we will undertake include:

-

Hand reference list researches of included studies.

-

Authors of relevant protocol papers identified by the electronic database searches will be contacted.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of review authors will independently screen titles and abstracts of all studies using Covidence software [45]. If discrepancies between reviewers cannot be resolved by consensus, a third reviewer will be consulted to inform study progression to full-text review. We will contact authors if study information to inform study inclusion is unavailable or unclear.

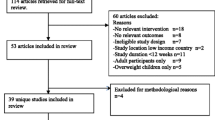

Full-text articles will be obtained for any study which could not clearly be excluded on the basis of study title and abstract. Full-text articles will be reviewed for their eligibility for inclusion by pairs of review authors. If discrepancies cannot be resolved by consensus, a third reviewer will be consulted to inform study inclusion. Reasons for excluding any full-text manuscripts will be documented at this stage, and we will record the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram [31].

Data extraction and management

Pairs of independent, un-blinded reviewers will extract data for included studies. If discrepancies between reviewers are not resolved by consensus, a third reviewer will be consulted for final decision-making.

For included studies, we will use a piloted and adapted version of the Cochrane Public Health data extraction template to extract data on:

-

Study characteristics: first author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, funding source;

-

Childcare service characteristics: type (centre-based (preschool or long day care) or family day care), operational characteristics (public or private; full-time or part-time), location (urban or rural);

-

Participant characteristics: age, gender, ethnicity;

-

Intervention characteristics: name of the programme, intervention description, duration, and intensity of the intervention;

-

Outcome definitions and time points of outcome measurement;

-

Study results relevant to our review outcomes;

-

Dropout/adherence rate;

-

Financial cost of the intervention;

-

Unintended adverse events of the intervention;

-

Conflict of interest, using the Tool for Addressing Conflicts of Interest in Trials (TACIT: http://tacit.one/).

Assessment of risk of bias

Individual study risk of bias will be independently assessed by two reviewers, using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias (RoB) tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [46]. Where required, a third review author will adjudicate discrepancies regarding RoB that could not be resolved via consensus.

For the purposes of this review, RoB domains of interest will be based on the effect of assignment, i.e. whether the interventions were effective regardless of whether the intervention was received as intended (the intention-to-treat effect) [47]. This was chosen as it is most appropriate for informing health policy questions about which interventions should be recommended.

The specific domains of bias reviewed will relate to:

-

Selection bias

-

Performance bias

-

Detection bias

-

Attrition bias

-

Reporting bias

-

Other bias

For cluster RCT, an additional domain will be assessed related to biases arising from the timing of identification and recruitment of participants [48]. Based on RoB assessment, RoB will be judged as ‘low’, ‘high’, or ‘unclear’ and will be used to summarise individual study results, as well as an overall study RoB [47].

Measures of treatment effect

If meta-analyses are performed, we will report the intervention effect for binary outcomes using risk ratios (RRs), and for continuous outcomes as the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) if different measures are used to assess the same outcome. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) will be calculated and reported for all estimated intervention effects [46].

Unit of analysis issues

We will extract data from trials that allocate either individuals or groups to a diet-focused intervention or control, or alternative non-diet-focused intervention. Data from cluster designed trials will be combined with other study outcome data if clustering has been appropriately accounted for. If clustering has not been accounted for in cluster trial analyses, relevant data including the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) and average cluster size will be sought and used to calculate the design effect and effective sample size to allow for inclusion of such trials in any meta-analyses [48].

Dealing with missing data

Missing data and dropouts in the included studies will be assessed and reported; this will include reported numbers as well as characteristics and reasons for dropout. The authors of the included studies will be contacted to obtain missing data if required. Evidence of potential reporting bias will be documented in the ‘Risk of Bias’ tables.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity may be present in the results of included studies due to differences in intervention types and study outcomes. However, provided that sufficient data is available, we will conduct a meta-analysis to quantify the overall effectiveness of interventions for our primary outcome (i.e. child diet). Heterogeneity will be evaluated using forest plots and examining them for asymmetry. In addition, we will quantify statistical heterogeneity by calculating the I2 statistic [49]. Study heterogeneity will be informed by a narrative description of study characteristics, and causes for study heterogeneity will be explored by subgroup analyses.

Assessment of reporting biases

We will assess reporting bias by comparing published reports with information provided in trial registers and protocols. Reporting bias will be explored in any meta-analyses conducted by plotting contour-enhanced funnel plots and visually assessing them for asymmetry and outliers. Given that small studies are consistently more likely to report positive effects, we will also evaluate the presence of reporting bias or differences in the results between smaller and larger studies.

Data synthesis

Provided there is adequate data available, we plan to pool measures of the same quantitative outcomes (primary and/or secondary), if the outcomes are comparable and sufficiently homogenous. If studies report multiple outcome measures relating to the same or a similar outcome being pooled, we will use the outcome measure used in the sample size calculation. If a sample size calculation is missing, the primary outcome will be identified by matching the outcome to the primary study aim. For trials with multiple follow-up periods, we will use outcome data from the final follow-up period reported.

Random effects meta-analyses will be used to calculate pooled effects. It is expected that a mix of change-from-baseline and post-intervention measurements will be reported and included in any meta-analyses, using recommended methods where possible [50].

In all instances where we cannot combine data in a meta-analysis, we will conduct a narrative summary of the trial findings in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Cochrane Handbook. This narrative summary will encompass vote counting based on the direction of intervention effect, as well as summarizing intervention effect estimates where available according to the review objectives [51].

GRADE and ‘Summary of findings’ table

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) will be used to assess the overall certainty of the available evidence for our primary outcome as recommended by the Cochrane handbook [52, 53]. These results will be presented in a ‘Summary of findings’ table. Based on our GRADE assessment, we will make decisions regarding our level of certainty that the estimates of the effect are correct. Our level of certainty will be presented as either high, moderate, low, or very low.

As per GRADE recommendations, the primary outcome measure will be assessed against eight GRADE criteria to obtain an overall GRADE rating and provide an overall level of certainty of the evidence. We will consider five criteria for lowering the level of certainty: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias. Following this, the level of certainty may be raised by three criteria: strong association between intervention and outcome, dose-response relationship, and where plausible confounders would have reduced the effect between intervention and outcome. Decisions to downgrade or upgrade the certainty of the evidence for each criterion will be documented using footnotes.

We will present the results in tables. These tables will also report on the number of included studies and participants, the treatment effect estimate, and the assessment of the overall certainty of the body of evidence for that outcome.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If significant heterogeneity is present, we will conduct subgroup analyses to explore the possible causes of heterogeneity. Provided sufficient data is available, we will explore heterogeneity across subgroups related to population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) characteristics.

Sensitivity analysis

The impact of the study methodological risk of bias will be explored in a sensitivity analysis. To do this, we will repeat any meta-analyses by excluding data from studies classified as a high risk of bias.

Discussion

Poor dietary intakes can have implications for child short-term and long-term health status [54]. As the ECEC setting provides significant opportunity to deliver public health interventions to improve child diet, identifying effective healthy eating interventions in this setting is critical for supporting population-wide obesity prevention efforts [55]. This systematic review seeks to provide an up-to-date synthesis of healthy eating interventions in ECEC services and describe their effect on child diet, anthropometrics, cardiovascular disease risk markers, and other related health outcomes including cognition, mental health, and quality of life.

Such a synthesis is particularly important in this sector as identifying effective interventions in this setting remains an ongoing area of global public health interest and investment [21]. Further, recognising the influence of this setting on child health and wellbeing, there has been a rapid progression of the evidence base, with a large number of RCTs being conducted in this setting in recent years. A review of RCTs provides level 1 evidence of causality to support policy and investment decisions [56]. Additionally, this review seeks to describe potential adverse events, and the absolute-cost/cost-effectiveness of ECEC-based healthy eating interventions, to further support the selection of interventions which are effective, safe, and cost-effective to deliver.

Publishing this systematic review protocol is expected to reduce the possibility of duplication and offers transparencies to the methods and processes used. It also allows outcomes to be pre-specified reducing the risk of reporting biases. Thus, any important protocol amendments will be recorded in PROSPERO. The results from the completed systematic review and meta-analysis will be presented at relevant national/international conferences and will be submitted for peer-review journal publication. The results of this systematic review are expected to support public health practitioners and policy decision-makers by summarising the updated evidence base for healthy eating interventions within the ECEC setting.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CBCL:

-

Child Behavioural Checklist

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- DONE:

-

Determinants of Nutrition and Eating

- ECEC:

-

Early childhood education and care

- EPOC:

-

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- ICC:

-

Intra-class correlation coefficient

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- PICO:

-

Participants, intervention, control, outcome

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- RoB:

-

Risk of bias

- RR:

-

Risk ratios

- SMD:

-

Standardised mean difference

- TACIT:

-

Tool for Addressing Conflicts of Interest in Trials

- QALY:

-

Quality-adjusted life years

References

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Data 2014 [cited 2019 Sept] Available from: http://www.healthdata.org/gbd/data.

Shrestha R, Copenhaver M. Long-term effects of childhood risk factors on cardiovascular health during adulthood. Clin Med Rev Vasc Health. 2015;7:1.

Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M. The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:100–8.

Deloitte Access Economics. The impact of increasing vegetable consumption on health expenditure 2016 [cited 2019 Sept]. Available from: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/Economics/deloitte-au-economics-increasing-vegetable-consumption-health-expenditure-impact-040716.pdf.

Waxman A. Prevention of chronic diseases: WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24(3):281–4.

Guerrero AD, Mao C, Fuller B, Bridges M, Franke T, Kuo AA. Racial and ethnic disparities in early childhood obesity: growth trajectories in body mass index. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3(1):129–37.

Koning M, Hoekstra T, de Jong E, Visscher TL, Seidell JC, Renders CM. Identifying developmental trajectories of body mass index in childhood using latent class growth (mixture) modelling: associations with dietary, sedentary and physical activity behaviors: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1128.

Rodrigues AN, Abreu GR, Resende RS, Goncalves WL, Gouvea SA. Cardiovascular risk factor investigation: a pediatric issue. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:57.

Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Newman WP, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(23):1650–6.

Castellano JM, Peñalvo JL, Bansilal S, Fuster V. Promotion of cardiovascular health at three stages of life: never too soon, never too late. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition). 2014;67(9):731–7.

Turco JV, Inal-Veith A, Fuster V. Cardiovascular health promotion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(8):908.

Piernas C, Popkin BM. Trends in snacking among US children. Health Aff. 2010;29(3):398–404.

Johnson B, Bell L, Zarnowiecki D, Rangan A, Golley R. Contribution of discretionary foods and drinks to Australian children’s intake of energy, saturated fat, added sugars and salt. Children. 2017;4(12):104.

Torii K, Fox S, Cloney D. Quality is key in early childhood education in Australia. Mitchell Institue Policy Paper No. 01/2017: Mitchell Institute, Melbourne; 2017. [cited 2019 Sept] Available from: http://www.mitchellinstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Quality-is-key-in-early-childhood-education-in-Australia.pdf.

Australian child care career options (ACCCO). Early childhood education and care 2019 [cited 2019 Sept] Available from: https://www.accco.com.au/courses/early-childhood-education-and-care/.

Baxter J. Child care and early childhood education in Australia (Fact Sheets 2015) Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies; 2015 [cited 2019 Sept] Available from: https://aifs.gov.au/publications/child-care-and-early-childhood-education-australia.

European Commission. Early childhood education and care. United Kingdom- England 2019 [cited 2019 Sept] Available from: https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/early-childhood-education-and-care-93_en.

Kamerman SB, Gatenio-Gabel S. Early childhood education and care in the United States: an overview of the current policy picture. Int J Child Care Educ Policy. 2007;1(1):23–34.

OECD- Social Policy Division - Directorate of Employment Labour and Soical Affairs. PF3.2: Enrolement in childcare and pre-school. OECD Family Database; 2019.

Neelon SEB, Briley ME. Position of the American Dietetic Association: benchmarks for nutrition in child care. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111(4):607–15.

World Health Organization. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity. Implementation plan: executive summary. 2017 [cited 2019 Sept] Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259349/WHO-NMH-PND-ECHO-17.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

Soanes R, Miller M, Begley A. Nutrient intakes of two-and three-year-old children: a comparison between those attending and not attending long day care centres. Aust J Nutr Diet. 2001;58(2):114–20.

Taguma M, Litjens I, Makowiecki K, Early QM. Quality matters in early childhood education and care Sweden. 2013. [cited 2020 May] Available from: http://www.oecd.org/education/school/SWEDEN%20policy%20profile%20-%20published%2005-02-2013.pdf.

Stok FM, Hoffmann S, Volkert D, Boeing H, Ensenauer R, Stelmach-Mardas M, et al. The DONE framework: creation, evaluation, and updating of an interdisciplinary, dynamic framework 2.0 of determinants of nutrition and eating. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0171077.

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Assurance. National Quality Standard. Quality Area 2- Children’s health and safety 2017 [cited 2019 Sept]. Available from: http://www.acecqa.gov.au/Childrens-health-and-safety.

Pinzon J. An analysis of meaningful performance measures for early childhood development. 2016. [cited 2019 Sept]. Available from: https://dspace.library.uvic.ca/bitstream/handle/1828/7636/Pinzon_Jaime_MPA_2016.pdf?sequence=1.

Matwiejczyk L, Mehta K, Scott J, Tonkin E, Coveney J. Characteristics of effective interventions promoting healthy eating for pre-schoolers in childcare settings: an umbrella review. Nutrients. 2018;10(3):293.

Nishtar S, Gluckman P, Armstrong T. Ending childhood obesity: a time for action. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):825–7.

Hennessy M, Byrne M, Laws R, Mc Sharry J, O’Malley G, Heary C. Childhood obesity prevention: priority areas for future research and barriers and facilitators to knowledge translation, coproduced using the nominal group technique. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9(4):759–67.

Milat AJ, Newson R, King L, Rissel C, Wolfenden L, Bauman A, et al. A guide to scaling up population health interventions. Public Health Res Pract. 2016;26(1):e2611604.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC resources for review authors. 2017.

OECD. Enrolment in childcare and pre-schools 2014 [cited 2019 Aug]. Available from: http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_2_Enrolment_in_childcare_and_preschools.pdf.

Ball SC, Benjamin SE, Ward DS. Development and reliability of an observation method to assess food intake of young children in child care. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107(4):656–61.

Lichtenberger EO. General measures of cognition for the preschool child. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11(3):197–208.

Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant development: Manual: Psychological Corporation; 1993.

Kaufman A, Kaufman N, inventors Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, 2nd Edition Manual. Circle Pines, MN: AGS2004.

Wechsler D. Manual for the l’echsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence–Revised. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1989.

Johnson J, D'Amato R. Test review of the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, 5th Edition: The Sixteenth Mental Measurements Yearbook; 2005.

Elliott CD, Murray G, Pearson L. Differential ability scales. San Antonio; 1990.

Howard SJ, Melhuish E. An early years toolbox for assessing early executive function, language, self-regulation, and social development: validity, reliability, and preliminary norms. J Psychoeduc Assess. 2017;35(3):255–75.

Einfeld SL, Tonge BJ. The Developmental Behavior Checklist: the development and validation of an instrument to assess behavioral and emotional disturbance in children and adolescents with mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord. 1995;25(2):81–104.

Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL™ 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39(8):800–12.

Wolfenden L, Jones J, Williams CM, Finch M, Wyse RJ, Kingsland M, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10.

Covidence. World-class systematic review management Available from: https://www.covidence.org/home.

Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1. 0: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Higgins JP, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JA. Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of. Interventions. 2019:205–28.

Higgins JP, Eldridge S, Li T. Including variants on randomized trials. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of. Interventions. 2019:569–93.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clin Res). 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG, Group CSM. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions; 2019. p. 241–84.

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE. Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; 2019. p. 321–47.

Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Akl EA, Kunz R, Vist G, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):383–94.

Schünemann HJ, Higgins JP, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Akl EA, Skoetz N, et al. Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; 2019. p. 375–402.

Lanigan J, Turnbull B, Singhal A. Toddler diets in the UK: deficiencies and imbalances 2. Relationship of toddler diet to later health: what toddlers eat is important as it affects their present and long-term health. Julie Lanigan and colleagues from the Institute of Child Health discuss the particular implications for obesity, dental caries and constipation. J Fam Health Care. 2007;17(6):197–201.

World Health Organization. Population-based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. 2012. [cited 2019 Aug] Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/80149/9789241504782_eng.pdf.

National Health and Medical Research Council. A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: NHMRC; 1999.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Debbie Booth, faculty librarian, University Library, the University of Newcastle, for supporting the development of our electronic database search strategy.

Funding

This work is support by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Centre for Research Excellence grant (grant number APP1153479). Infrastructure funding provided by Hunter New England (HNE) Health, University of Newcastle (UoN), and Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI). Associate professor Luke Wolfenden receives salary support from NHMRC career development fellowship (APP1128348) and Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship (101175). Dr. Sze Lin Yoong is a postdoctoral research fellow funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award (G1600359). Funding sources had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during its execution, analyses, or interpretation of results.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJ led the drafting of the manuscript. JJ, LW, AH, and SLY contributed to the design of the systematic review. All authors contributed to the development and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval will not be required given individual participant information will not be used. The results of this systematic review will be disseminated through peer-review publications or conference presentations. Any essential protocol amendments will be documented in the full review.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jackson, J., Wolfenden, L., Grady, A. et al. Early childhood education and care-based healthy eating interventions for improving child diet: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev 9, 181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01440-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01440-4