Abstract

Background

This work aimed to identify studies of interventions seeking to address mental health inequalities, studies assessing the economic impact of such interventions and factors which act as barriers and those that can facilitate interventions to address inequalities in mental health care.

Methods

A systematic mapping method was chosen. Studies were included if they: (1) focused on a population with: (a) mental health disorders, (b) protected or other characteristics putting them at risk of experiencing mental health inequalities; (2) addressed an intervention focused on addressing mental health inequalities; and (3) met criteria for one or more of three research questions: (i) primary research studies (any study design) or systematic reviews reporting effectiveness findings for an intervention or interventions, (ii) studies reporting economic evaluation findings, (iii) primary research studies (any study design) or systematic reviews identifying or describing, potential barriers or facilitators to interventions.

A bibliographic search of MEDLINE, HMIC, ASSIA, Social Policy & Practice, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts and PsycINFO spanned January 2008 to December 2018.

Study selection was performed according to inclusion criteria. Data were extracted and tabulated to map studies and summarise published research on mental health inequalities. A visual representation of the mapping review (a mapping diagram) is included.

Results

Overall, 128 studies met inclusion criteria: 115 primary studies and 13 systematic reviews. Of those, 94 looked at interventions, 6 at cost-effectiveness and 36 at barriers and facilitators. An existing taxonomy of disparities interventions was used and modified to categorise interventions by type and strategy. Most of the identified interventions focused on addressing socioeconomic factors, race disparities and age-related issues. The most frequently used intervention strategy was providing psychological support. Barriers and associated facilitators were categorised into groups including (not limited to) access to care, communication issues and financial constraints.

Conclusions

The mapping review was useful in assessing the spread of literature and identifying highly researched areas versus prominent gaps. The findings are useful for clinicians, commissioners and service providers seeking to understand strategies to support the advancement of mental health equality for different populations and could be used to inform further research and support local decision-making.

Systematic review registration

Not applicable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Profound inequalities exist in the access to, experience and outcomes of mental health support for many marginalised or minority communities in the UK [1, 2]. While a number of these characteristics are legally protected by the Equality Act 2010 (race, gender and sexual orientation) [3], and despite National Health Service (NHS) commissioners being statutorily bound by the Health and Social Care Act 2012 [4] to reduce health inequalities, inequities persist, particularly within mental health care where individuals may face an additional level of stigmatisation or discrimination [5]. Accumulating evidence has also established unsatisfactory experiences and outcomes of mental health care in individuals affected by social determinants of poorer health [6, 7] including, but not limited to, socioeconomic deprivation, homelessness and transitional housing and asylum seeker or refugee status [2, 8, 9]. Furthermore, individuals with more than one of these features or protected characteristics are likely to be at further disadvantage, in line with the theory of intersectionality [10].

To reduce the disadvantage associated with these inequalities, meaningful and effective strategies need to be developed. Furthermore, tackling inequalities in mental health care can significantly benefit the wider economy. Consistent evidence suggests that improving access to, and experience of, mental health care can reduce the economic burden of illness and bring long-term cost savings associated with enhanced employability, fewer lost work hours and reduced utilisation of costly health services [11]. To truly bring about effective change and improve outcomes, innovative practice is required at all layers of care to promote cultural, structural and attitudinal shifts.

The NHS has committed to prioritising the reduction of health inequalities in both the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health [12] and, more recently, the NHS Long Term Plan [13]. Contemporary models of mental health care in high-income countries are primarily based on concepts of mental health and well-being derived from Western culture, and as such, do not necessarily consider cultural and social diversity [14]. Therefore, one way to advance mental health equality may be to commission, or improve uptake of, evidence-based interventions specifically targeted at communities that face inequalities. There is a growing literature base of ‘disparity interventions’ which aim to adapt existing interventions in such communities or develop new interventions tailored to the community of interest. To bring about change, it is important to understand what interventions have been attempted, their effects and overall costs, as well as barriers and facilitators to uptake and success.

This review is part of a larger piece of work—Advancing Mental Health Equality (AMHE) [15], which was commissioned by NHS England as part of the Mental Health Care Pathways programme. The review aims to map the existing literature on disparity interventions in order to inform the delivery of more effective and culturally appropriate care and, ultimately, advance mental health equality.

Methods

Study design: systematic map

Systematic mapping reviews aim to draw together existing studies in a specific topic area and develop an understanding of the available data as well as any potential gaps [16,17,18,19,20]. There is no authoritative methodological guidance on how to conduct a systematic mapping review, such as exists for instance for a systematic review [20]. Researchers have gravitated towards a systematic process of study identification, screening and data extraction [20, 21], so that it is clear how the maps have been created. However, research questions are commonly broader in mapping reviews than in systematic reviews [22], study quality is not appraised or graded, and data are presented in a tabular or visual format rather than analysed or fully synthesised [16, 17, 20, 21].

Systematic mapping was chosen as the method for this work since we aimed to understand the studies and data available with a view to establishing further research priorities. The maps are used to consolidate studies in the broad research area of interventions to address mental health inequalities experienced by marginalised or minority communities.

Research questions and objectives

The research questions were as follows:

-

1.

What studies are there on interventions to address or reduce mental health inequalities?

The objective of this research question was to identify the existing interventions which seek to address mental health inequalities.

-

2.

What are the data from economic evaluations for interventions to address or reduce inequalities in mental health care?

The objective here was to identify studies that assess the economic impact of interventions to address inequalities in mental health care.

-

3.

What are the barriers and facilitators to interventions to address or reduce mental health inequalities?

The objective of the third question was to identify factors which act as barriers and those that can facilitate interventions which seek to address mental health inequalities.

To develop the research questions, we worked with stakeholders and methodologists [16], scoped the literature and informally reviewed the evidence base to identify relevant studies [23]. The purpose was to determine suitable research questions and use these to develop the approach to study identification, as well as pilot inclusion criteria and data extraction for the mapping review [23, 24]. We convened a group of stakeholders to inform the development of this review as part of the AMHE resource [15] developed at the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH). Stakeholders included people with lived experience of mental health problems, informal carers and people with one or more of the characteristics outlined in Table 1. We also consulted experts in the field of mental health and equalities research; mental health care professionals, including psychiatrists, mental health nurses, approved mental health professionals (AMHPs); and staff working in equality lead roles in the NHS. They contributed to the development of the research questions through a series of focus groups and workshops [15]. They were also integral to the work on the categorisation of barriers. Stakeholders were informed of the progress of the review and had an opportunity to advise further in subsequent meetings and via email.

Definitions

Mental health inequalities and inequities

‘Mental health inequalities’ are defined in this work as differences between population groups in their mental health status and outcomes, including the following:

-

the prevention of mental ill health;

-

access to and experience of mental health care; and

-

outcomes associated with mental ill health.

‘Mental health inequities’ are avoidable inequalities between population groups. They arise from social and material inequalities within society, such as discrimination, stigma and distribution of wealth and resources [25]. This study considers interventions addressing mental health inequities; however, because there is a lack of clear differentiation between definitions of inequity and inequality within the literature, the term ‘mental health inequality’ is used.

The population, intervention, outcomes and study designs

Population

In this work, the targeted population is defined as people who meet at least one criterion from each of the two types of criteria pertaining to: (a) disorder/problem type AND (b) having one or more specific characteristics.

-

A.

Population: Disorder/problem type

People who have a diagnosis, or who are at risk, of any of the following mental health conditions/disorders or problems:

-

anxiety

-

bipolar disorder

-

antisocial behaviour and conduct disorders (in children and young people)

-

depression

-

eating disorders

-

mental health problems in the pregnancy and postnatal period

-

personality disorders

-

psychosis and schizophrenia

-

self-harm.

This list is derived from the National institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE) categorisation of guidance and pathways for the above specified conditions [26]. We have cross-referenced the list with the International Classification of Diseases’ (ICD-10) [27] classification of mental health disorders for conditions that fall under the categories of:

-

F20-29: Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders

-

F30-39: Mood (affective) disorders

-

F40-48: Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders

-

F60-69: Disorders of personality and behaviour in adult persons

-

F91: Conduct disorders (in: Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence)

-

B.

Population: Having specific characteristics

People who have one or more of the characteristics outlined in equality impact assessments used by NICE in the development of guidelines. These characteristics served as a basis; we broke them down to identify the specific areas that we wished to focus on (see Table 1).

Intervention

In this work, an ‘intervention’ refers to any type of purposeful act, programme, system or deliverable that has been put in place with the intention of addressing or reducing mental health inequality or that is targeted at a specific group at risk of experiencing mental health inequality. These can include treatment interventions, targeted adaptations of existing treatments, policies, intentional organisational or structural changes.

Outcomes

This relates to the research questions, such that for research question 1, the outcomes relate to the effectiveness of interventions measured, for example, using relevant clinician- or patient-rated scales (such as symptom severity scales or quality of life measures) or access rates; for research question 2, the outcome is economic in nature, such as a cost-benefit; and for research question 3, the outcome is any actual or perceived barrier or facilitator to intervention uptake and/or success for which themes were extracted.

Study design

By research question:

-

Research question 1: any primary study evaluating effectiveness

-

Research question 2: any economic evaluation

-

Research question 3: any primary study evaluating barriers and/or facilitators to intervention uptake.

Systematic reviews were included but they are reported separately to studies identified above and in their own table (see Additional file 3). Editorials, commentaries and letters were not included.

Search strategy

Study identification (literature search) was undertaken by a qualified information specialist. The following bibliographic databases were systematically searched:

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process via Ovid

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) via Ovid

-

Applied Social Sciences Index Abstracts (ASSIA) via ProQuest

-

Social Policy & Practice via Ovid

-

Sociological Abstracts via ProQuest

-

Social Services Abstracts via ProQuest

-

PsycINFO via Ovid.

The full search strategy can be found in Additional file 1 and takes the following form: (terms for mental health) and (terms for inequalities and reduce) and (terms for economics, meta-analysis, systematic reviews, observational studies, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and barriers and facilitators). The searches were not limited by language and spanned the period from January 2008 to December 2018, a timeframe the authors considered to be within resource limits [28] and agreed with select stakeholders. The search strategies were reviewed by the research team using the PRESS checklist [29]. Resources did not permit the inclusion of the Embase database.

Study selection

Studies were double-screened according to the pre-determined inclusion criteria. Title/abstract screening was undertaken using the desktop Rayyan application [30] and resulted in 97.1% agreement. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with the wider review team.

Inclusion criteria

For all research questions, to be included in the review the studies had to:

-

Focus on a population with:

-

a.

Mental health disorders, conditions or problems that meet the definition for population in this review, and

-

b.

Focus on a population group with protected or other characteristics identified as at risk of experiencing mental health inequalities (see Table 1), and

-

a.

-

Address an intervention, as defined by this review, focused on addressing or reducing mental health inequalities, and

-

Meet the following criteria for one or more of the research questions:

-

a.

Research question 1: be a primary research study (any study design) or systematic review reporting effectiveness findings for an intervention or interventions

-

b.

Research question 2: report the findings of an economic evaluation; include sufficient detail regarding methods and results; the study’s data and results to be extractable (full economic evaluations that compare two or more relevant options and considered both costs and consequences; costing analyses that compared only costs between two or more interventions; and non-comparative studies were all included)

-

c.

Research question 3: be a primary research study (any study design) or systematic review identifying and categorising, describing or explaining, potential barriers or facilitators to intervention uptake or success.

Data extraction

Where possible, data were extracted from title/abstract, which is consistent with methods of the other mapping reviews [20]. Where study abstracts were insufficient in providing the data required for extraction, lacked clarity or there was any doubt, full texts were retrieved and the relevant data extracted. For primary studies, we extracted study aims, study design, population (sample), population characteristic(s) associated with inequality, intervention details, intervention types and strategies (as applicable), comparator (as applicable) and outcomes. We also extracted currency for primary studies answering research question 2 and outcomes and/or themes for those answering research question 3. For systematic reviews we extracted study aims, included studies, population characteristic(s) associated with inequality, intervention details, intervention types and strategies, comparator(s) (as applicable) and outcomes. For systematic reviews to answer research question 3, we extracted themes pertaining to barriers and facilitators. Data extracted by one researcher were always double-checked by another. The data extraction tables are set out in Additional files 2 & 3.

Study quality (risk of bias)

Study quality was not appraised.

Results

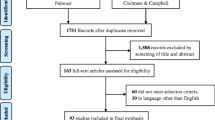

The overarching findings from the study identification and screening processes are reported to PRISMA reporting guidance; a PRISMA flow chart [31] is included (Fig. 1).

The inclusion criteria were met by 128 studies; 115 were primary studies [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146] and 13 were systematic reviews [147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159]. Relevant data were extracted and tabulated to map the studies (additional file 2); separate tables summarised relevant systematic reviews (see Table 2 and additional file 3). Maps were used to consolidate primary studies that addressed the broad research area of mental health inequalities. Using Adobe Illustrator [160], we also developed a visual representation of the mapping review in the form of a mapping diagram (Fig. 2).

Mapping diagram of primary studies. *Studies examining these characteristics were only included if they also looked at other characteristics. **Specific populations are those who may have a specific set of characteristics and experiences placing them at risk of experiencing mental health inequalities and therefore may already be defined by multiple characteristics (e.g. refugees). Circle size area is asscociated with the number of primary studies that consider a population characteristic. The lines between the circles indicate where characteristics were considered together, while the thickness of the lines indicates the frequency of the association. 49 studies examined 2 population characteristics; the most frequent association was between age and socioeconomic factors. 24 studies examined 3 characteristics, of which age, race and socioeconomic factors were the most frequent associations. 8 studies examined 4 characteristics. 3 studies examined 5 characteristics. 3 studies examined 6 characteristics

We identified 94 studies that addressed research question 1, 6 that addressed research question 2 and 36 that addressed research question 3; some studies were relevant to more than one question. An existing taxonomy of disparities interventions [161] was used and modified by way of expansion (Table 3), to categorise interventions by type (access, early intervention, intervention, prevention) and strategy (Table 4). Target populations in primary studies were categorised by a range of characteristics and characteristic sub-types (Table 5). It should be noted that characteristic sub-types may or may not be mutually exclusive; therefore, the ‘Number of studies by characteristic’ column in Table 5 does not offer a summative count. The mapping diagram (Fig. 2) presents the findings of the mapping review with reference to the number of primary studies that consider different population characteristics and the frequency with which multiple characteristics are considered together across studies.

For research question 1, we identified 94 studies of interventions that aimed to address mental health inequalities: 85 primary studies and 9 systematic reviews. A total of 74 unique interventions were identified across primary studies.

We categorised primary study target populations according to the following characteristics: socioeconomic factors (n = 65), age (n = 46), race/ethnicity (n = 29), location (n = 17), pregnancy and maternity (n = 14), sex (n = 10), ‘specific intersectional groups’ (homeless people, youth offenders and refugees; n = 6), ‘other’ (n = 6), disability (n = 3), sexual orientation and gender identity (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and others (LGBTQ+); n = 2) and religion (n = 2) (see Table 5). The mapping diagram (Fig. 2) presents the number of primary studies that consider different population characteristics using circle area, e.g. the circle for socioeconomic factors is largest, while the circle for religion is smallest. The lines connecting the circles indicate characteristics considered together, with thickness of the connecting lines showing frequency of that association. Forty-nine studies examined 2 population characteristics; the most frequent association was between age and socioeconomic factors. Twenty-four studies examined 3 characteristics, of which age, race and socioeconomic factors were the most frequent associations.

Countries in which primary studies were conducted were also recorded (Table 6), with the majority conducted in the USA (n = 34) and the UK (n = 17).

Intervention strategies used most frequently in primary studies were providing psychological support (n = 45), delivering education and training (n = 29), engaging the community (n = 26) and other—culturally adapted interventions (n = 26) (Table 4). The most frequently reported intervention strategy in systematic reviews was other—culturally adapted interventions (n = 5) followed by providing psychological support (n = 4). As with the primary studies, most of the reviews focused on targeting populations based on socioeconomic factors (n = 6). The systematic reviews we identified, including information on intervention types, strategies and target populations, are summarised in Table 2.

For research question 2, only 6 economic evaluations were included (Table 7); these were cost-effectiveness studies of which 3 were also identified in research question 1 [100, 119, 152]. Five studies examined population variables related to socioeconomic factors: 3 studies were of children [100, 108, 152], 1 looked at pregnant women [79] and another at adults eligible for Medicaid in the USA [119]. The last study examined the cost-effectiveness of a health-check intervention for people with learning disabilities [121]. All three cost-effectiveness studies of children with low socioeconomic factors examined the Incredible Years parenting programme. All cost-effectiveness studies were conducted in either the USA or Europe.

For research question 3, we identified barriers and facilitators to interventions aimed at addressing mental health inequalities, including the populations with whom certain interventions are used (Table 8).

Using the input from the lived experience members of the stakeholder group, we categorised the types of barriers reported in the literature (36 studies) into 8 groups: (1) limited treatment options and service limitations, (2) perceived or real discrimination, (3) access to care, (4) financial constraints, (5) communication issues, (6) awareness of available services, (7) trust in services or ‘the system’, (8) appropriateness of available services. Of the 36 included studies, 34 reported information on barriers in their findings, while only 20 reported on facilitators (Table 8).

Discussion

Research question 1: What studies are there on interventions to address or reduce mental health inequalities?

The majority (80%) of primary studies focused on targeting populations based on socioeconomic factors (n = 65), age (children and young people as well as older adults; n = 46) and race/ethnicity (ethnic minorities and indigenous/aboriginal populations; n = 29), indicating that these populations are most frequently targeted in interventions to address mental health inequalities in the published literature. However, it should also be noted that the majority of the included studies were conducted in the USA or the UK, limiting the ability to generalise these findings to other countries. We identified very few primary studies targeting populations on the basis of religious affiliation (n = 2), sexual or gender identity and sexual orientation (LGBTQ+; n = 2) and disability (n = 3), and none of the systematic reviews targeted these populations. These findings warrant further investigation as we are unable to conclude, through use of a mapping review, the reasons for these observations. It is likely that these findings might be indicative of the current state of the literature on availability of interventions for these populations. Further and more focused research on interventions designed for these specific populations is needed.

Identification of intervention strategies used to address inequalities across studies, by frequency, is an interesting finding of this mapping review. However, on its own this finding is of limited use and would be more informative when analysed in conjunction with other research on the effectiveness of these strategies with different populations, to better understand what works for different at-risk groups.

Research question 2: What are the data from economic evaluations for interventions to address or reduce inequalities in mental health care?

Only 6 economic evaluation studies were identified, limiting our ability to adequately address this research question and form a representative picture of the state of the cost-effectiveness literature regarding interventions aimed at addressing mental health inequalities. Half of the included studies were also analysed in research question 1, where the authors had performed a cost-effectiveness analysis as part of the study.

Research question 3: What are the barriers and facilitators to interventions to address or reduce mental health inequalities?

The identification of 8 types of barriers in the literature suggests that addressing inequalities in mental health care may be hindered by several factors, other than those that tend to be most commonly discussed, such as access to care [147, 162,163,164,165] and service integration [166]. The identification and categorisation of barriers and associated facilitators to interventions aimed at tackling inequalities is, therefore, a useful outcome of this mapping review. An understanding of barriers and facilitators can inform future intervention design, clinical practice, service organisation and methods of care delivery. We were able to identify where interventions are likely to encounter challenges in meeting their aims, while also summarising solutions and potentially helpful guidance around what could work. We were also able to identify the population groups that appear at risk of experiencing barriers. Future research should look more deeply at the effectiveness of facilitating factors in improving equality for people from at-risk population groups.

Strengths and limitations

This review demonstrates a number of important strengths. First, the protocol was informed by expert opinion with sustained input from expert stakeholders, including those with lived experience of mental health problems and related inequalities. This approach ensured that the direction of the research was both person-centred and reflected the priorities of the target populations. The input from clinicians also ensured the research held practical applicability and could be translated to clinical practice. In addition, the search strategy was broad, incorporating a range of pervasive cultural, social and intersectional inequalities. Similarly, the articles covered a wide geographical range across several continents and were not excluded on the basis of language. This approach is particularly pertinent for health equity research and ensures that geographical inequalities are also represented within the literature base.

We should also acknowledge the caveats. First, while a systematic approach was taken, it is not comparable with a full systematic review as only select databases were chosen; we did not search Embase and we were unable to search grey literature. To address research question 3, the search approach taken used a pragmatic cluster of search terms to focus the study identification on the barriers and facilitators to advancing mental health equality. The aim was to identify relevant studies within a manageable volume of studies to screen. It is possible that some studies have been overlooked by this approach and future work may look at the use of different terms. The timeframe for our literature search was narrowed to 2008–2018. We decided on a decade span between the authors and with input from stakeholders, as it was considered to be within resource limits, following guidance in the Cochrane Handbook [28]. As a result of this approach, it is possible that a relevant body of literature has been missed. In particular, considering the lack of literature pertaining to research question 2, it would be beneficial to conduct a full and focused systematic review in the future, to both provide a more encompassing review of the literature and gain a greater insight into the economic effectiveness of these interventions. Furthermore, as this is a mapping review, we did not assess the quality of each study, nor did we determine the effectiveness of the interventions. As such, the findings report the breadth of the data available, but it would be inappropriate to make any firm recommendations. Data were extracted from title/abstract where possible, with extraction from full text only performed when abstracts either lacked the data required or were unclear. While this method of extraction is both efficient and consistent with other mapping reviews [20], it does carry a risk of potentially relevant information being missed.

A further limitation arises from the problematic nature of categorising communities in the literature. The LGBTQ+ movement represents a diverse range of communities, each with unique needs and social perceptions; for example, the transgender community may face entirely different social issues and experiences of care compared with the lesbian community, and so on. Within the literature, however, these distinct groups were often amalgamated under one overarching label and, as such, it was difficult to separate the findings for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer communities. Similarly, the Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) label amalgamates a number of distinct cultures and ethnicities with heterogeneous experiences. Much of the literature did not make any further distinctions, once again limiting our ability to draw distinct conclusions for each component group. This approach limits the practical applicability of academic research concerning these communities and highlights a further pervasive inequality to which they are subjected. Ultimately, this requires a more nuanced, accurate reporting within future academic research involving these communities to ensure care can be tailored to their unique needs.

The stipulation applied to our inclusion criteria regarding population characteristics for age, sex and pregnancy and maternity is potentially problematic. This is because, to be considered eligible for inclusion in the review, studies of these populations needed to include people who have another characteristic or need that puts them at risk of experiencing inequalities. Our reasoning for this decision was to avoid including studies of participants from these groups who did not have an identifiable inequality. For example, studies of children and young people as such may not focus on addressing inequalities but might have been included inappropriately had it not been for the caveat applied here. Still, even though necessary, it is possible that the caveat meant that some potentially relevant studies were excluded.

Based on these limitations, we recommend a full systematic review for each of the characteristic sub-types to gain greater insights into the effectiveness of interventions to tackle mental health inequalities and inform national delivery of care for different population groups.

Conclusions

The mapping review indicated that the majority of mental health inequality interventions identified in this study focus on addressing socioeconomic factors, race disparities and age-related issues (most of which pertain to children and/or young people). The majority of interventions tend to use providing psychological support and delivering education and training as strategies. The review also identified population groups who may be at risk of experiencing barriers to interventions aimed at addressing inequalities. This knowledge is useful for commissioners and service providers seeking to understand what can be done to support the advancement of mental health equality for different populations. The information gained from the mapping review should be used to inform the direction of further research that could influence local commissioning and service provision.

The mapping review was useful in assessing the spread of literature across sub-topics and identifying the highly researched areas (which include interventions aimed at minority races; addressing socioeconomic factors; and age-related inequality issues) versus the prominent gaps (including interventions aimed at marginalised religious groups; the differing and unique needs of groups within the LGBTQ+ community; and people with disabilities). This map supports the identification of these potential gaps in existing research and assists in setting out future research priorities.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the study. Information relevant to this study can be accessed in the additional files.

Abbreviations

- AMHE:

-

Advancing Mental Health Equality

- AMHP:

-

Approved mental health professional

- BAME:

-

Black, Asian and minority ethnic

- CYP:

-

Children and young people

- DET:

-

Delivering education and training

- EC:

-

Engaging the community

- ELLS:

-

Enhancing language, literacy and communication

- IAPT:

-

Improving access to psychological therapies

- IASCT:

-

Improving access to support, care and treatment for mental health problems

- IATS:

-

Improving access to testing and screening

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- LGBTQ+:

-

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and others

- NICE:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NOS:

-

Not otherwise specified

- OCA:

-

Other—culturally adapted interventions

- OCR:

-

Other—community revitalisation

- OHBC:

-

Other—home-based care

- O-NOS:

-

Other—not otherwise specified

- OT:

-

Other—technology

- PFIP:

-

Providing financial incentives or removing financial barriers

- PPS:

-

Providing psychological support

- PRF:

-

Providing reminders and feedback

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- RSCT:

-

Restructuring the care team

References

Department of Health and Social Care. Modernising the Mental Health Act: increasing choice, reducing compulsion. Final report of the Independent Review of the Mental Health Act 1983. UK: Department of Health & Social Care; 2018. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/778897/Modernising_the_Mental_Health_Act_-_increasing_choice__reducing_compulsion.pdf.

Marmot M, Allen J, Goldblatt P, Boyce T, McNeish D, Grady M, et al. Fair society, healthy lives. The marmot review. Strategic review of health inequalities in England Post-2010. London: The Marmot Review; 2010. Available from: https://www.parliament.uk/documents/fair-society-healthy-lives-full-report.pdf.

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Equality act. London: The Stationery Office; 2010.

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Health and social care act. London: The Stationery Office; 2012.

Sartorius N. Stigma and mental health. Lancet. 2007;370(9590):810–1.

Irwin A, Valentine N, Brown C, Loewenson R, Solar O, Brown H, et al. The commission on social determinants of health: tackling the social roots of health inequities. PLoS Med. 2006; Available from: http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.0030106.

Kaplan G. Social determinants of health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. International journal of epidemiology. 2nd ed; 2006. p. 35.

Aspinall P, Watters C. Refugees and asylum seekers: a review from an equality and human rights perspective. Research report 52. Equality and human rights commission. 2010.

Rae BE, Rees S. The perceptions of homeless people regarding their healthcare needs and experiences of receiving health care. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(9):2096–107.

Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. The University of Chicago Legal Forum; 1989.

Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M. Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: the economic case. London: Department of Health; 2011.

The Mental Health Taskforce. The five year forward view for mental health. A report from the independent mental health taskforce to the NHS in England [internet]. London: NHS England; 2016. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Mental-Health-Taskforce-FYFV-final.pdf.

NHS England. The NHS long term plan [internet]. London: NHS England; 2019. Available from: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/.

Gopalkrishnan N. Cultural diversity and mental health: considerations for policy and practice. Front Public Health. 2018;6 [cited 2019 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00179/full.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Advancing mental health equality: steps and guidance on commissioning and delivering equality in mental health care. London: National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health; 2019. Available from: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/nccmh/amhe/amhe-resource.pdf.

Bates S, Clapton J, Coren E. Systematic maps to support the evidence base in social care. Evid Policy. 2007;3(4):539–51.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic reviews – CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare. York: Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2009. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Systematic_Reviews.pdf.

Cooper C, Rogers M, Bethel A, Briscoe S, Lowe J. A mapping review of the literature on UK-focused health and social care databases. Health Inf Libr J. 2015;32(1):5–22.

Cooper ID. What is a “mapping study?”. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(1):76–8.

Miake-Lye IM, Hempel S, Shanman R, Shekelle PG. What is an evidence map? A systematic review of published evidence maps and their definitions, methods, and products. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1) [cited 2019 Jul 15]. Available from: http://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0204-x.

Collaboration for Environmental Evidence. Guidelines for systematic review and evidence synthesis in environmental management. Bangor: Environmental Evidence; 2013. Available from: http://www.environmentalevidence.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Review-guidelines-version-4.2-final-update.pdf.

Rebelo Da Silva N, Zaranyika H, Langer L, Randall N, Muchiri E, Stewart R. Making the most of what we already know: a three-stage approach to systematic reviewing. Eval Rev. 2017;41(2):155–72.

Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. “Scoping the scope” of a Cochrane review. J Public Health. 2011;33(1):147–50.

Cooper C, Lovell R, Husk K, Booth A, Garside R. Supplementary search methods were more effective and offered better value than bibliographic database searching: a case study from public health and environmental enhancement. Res Synth Methods. 2018;9(2):195–223.

World Health Organization. WHO | Key concepts | What are health inequities or inequalities?. WHO. [cited 2020 Jan 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/key_concepts/en/.

National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE). Mental health and behavioural conditions. London: National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE); 2018. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases/mental-health-and-behavioural-conditions.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. Available from: https://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/bluebook.pdf.

Lefebvre C, Glanville J, Briscoe S, Littlewood A, Marshall C, Metzendorf M-I, et al. Chapter 4: searching for and selecting studies. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 60 (updated July 2019). Cochrane; 2019. Available from: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–6.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1) [cited 2019 Jul 15]. Available from: http://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Platell M, Cook A, Martin K. Barriers to mental health care for disadvantaged adolescents: perspectives of service providers. Adv Ment Health. 2017;15(2):198–210.

Baba JT, Brolan CE, Hill PS. Aboriginal medical services cure more than illness: a qualitative study of how indigenous services address the health impacts of discrimination in Brisbane communities. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13:56.

Bogenschutz M. “We find a way”: challenges and facilitators for health care access among immigrants and refugees with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Med Care. 2014;52(10):S64–70.

Glick G, Druss B, Conde M, Lally C, Pina J. Use of mobile technology in a community mental health setting. J Telemed Telecare. 2016;22(7):430–5.

Hailemariam M, Fekadu A, Selamu M, Medhin G, Prince M, Hanlon C. Equitable access to integrated primary mental healthcare for people with severe mental disorders in Ethiopia: a formative study. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):121.

Hepworth J, Askew D, Foley W, Duthie D, Shuter P, Combo M, et al. How an urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care service improved access to mental health care. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:51.

Krause M, Espinosa-Duque HD, Tomicic A, Cordoba AC, Vasquez D. Psychotherapy for depression from the point of view of economically disadvantaged individuals in Chile and Colombia. Couns Psychother Res. 2018;18(2):178–89.

Leahy D, Schaffalitzky E, Saunders J, Armstrong C, Meagher D, Ryan P, et al. Role of the general practitioner in providing early intervention for youth mental health: a mixed methods investigation. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2018;12(2):202–16.

Wallin EE, Mattsson S, Olsson EM. The preference for internet-based psychological interventions by individuals without past or current use of mental health treatment delivered online: a survey study with mixed-methods analysis. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3(2):e25.

Zarnowiecki D, Nguyen H, Catherine H, Boffa J, Segal L. The Australian nurse-family partnership program for aboriginal mothers and babies: describing client complexity and implications for program delivery. Midwifery. 2018;65:72–81.

Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Gilden D, Burns M, Huskamp HA, et al. Effects of eliminating drug caps on racial differences in antidepressant use among dual enrollees with diabetes and depression. Clin Ther. 2015;37(3):597–609.

Dalton JA, Rodger D, Wilmore M, Humphreys S, Skuse A, Roberts CT, et al. The Health-e Babies App for antenatal education: feasibility for socially disadvantaged women. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0194337.

De Silva T, Prakash A, Yarlagadda S, Johns MD, Sandy K, Hansen V, et al. General practitioners’ experiences and perceptions of mild moderate depression management and factors influencing effective service delivery in rural Australian communities: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2017;11:54.

Knifton L. Understanding and addressing the stigma of mental illness with ethnic minority communities. Health Sociol Rev. 2012;21(3):287–98.

Dowrick C, Bower P, Chew-Graham C. Evaluating a complex model designed to increase access to high quality primary mental health care for under-served groups: a multi-method study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):58.

McEvoy P, Williamson T, Gask L, Kada R, Frazer D, Dhliwayo C. Improving access to mental health care in an orthodox Jewish community: a critical reflection upon the accommodation of otherness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):557.

Gibson KL, Coulson H, Miles R, Kakekakekung C, Daniels E, O’Donnell S. Conversations on telemental health: listening to remote and rural first nations communities. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11(2):1656.

Aggarwal NK, Cedeno K, Guarnaccia P, Kleinman A, Lewis-Fernandez R. The meanings of cultural competence in mental health: an exploratory focus group study with patients, clinicians, and administrators. Springerplus. 2016;5:384.

Allerton L, Emerson E. British adults with chronic health conditions or impairments face significant barriers to accessing health services. Public Health. 2012;126(11):920–7.

Barnes J, Senior R, Macpherson K. The utility of volunteer home-visiting support to prevent maternal depression in the first year of life. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(6):807–16.

Bassilios B, Pirkis J, Fletcher J, Burgess P, Gurrin L, King K, et al. The complementarity of two major Australian primary mental health care initiatives. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(11):997–1004.

Bassilios B, Nicholas A, Reifels L, King K, Fletcher J, Machlin A, et al. Achievements of the Australian Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS) program: summarising (almost) a decade of key evaluation data. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2016;10:61.

Beeber LS, Schwartz TA, Holditch-Davis D, Canuso R, Lewis V, Hall HW. Parenting enhancement, interpersonal psychotherapy to reduce depression in low-income mothers of infants and toddlers: a randomized trial. Nurs Res. 2013;62(2):82–90.

Brown JS, Ferner H, Wingrove J, Aschan L, Hatch SL, Hotopf M. How equitable are psychological therapy services in South East London now? A comparison of referrals to a new psychological therapy service with participants in a psychiatric morbidity survey in the same London borough. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(12):1893–902.

Burra TA, Hwang SW, Rourke SB, Stergiopoulos V. Homeless and housed inpatients with schizophrenia: disparities in service access upon discharge from hospital. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2012;10(5):778–89.

Chinn D, Abraham E. Using “candidacy” as a framework for understanding access to mainstream psychological treatment for people with intellectual disabilities and common mental health problems within the English improving access to psychological therapies service. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2016;60(6):571–82.

Clarke AM, Bunting B, Barry MM. Evaluating the implementation of a school-based emotional well-being programme: a cluster randomized controlled trial of Zippy’s friends for children in disadvantaged primary schools. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(5):786–98.

Clemans-Cope L, Kenney G, Waidmann T, Huntress M, Anderson N. How well is CHIP addressing health care access and affordability for children? Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(3):S71–7.

Comiskey CM, O’Sullivan K, Quirke MB, Wynne C, Hollywood E, McGilloway S. An analysis of the first implementation and impact of the World Health Organisation’s health promoting school model within disadvantaged city schools in Ireland. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2015;10(4):281–93.

Cooley-Strickland MR, Griffin RS, Darney D, Otte K, Ko J. Urban African American youth exposed to community violence: a school-based anxiety preventive intervention efficacy study. J Prev Interv Community. 2011;39(2):149–66.

Cristofalo M, Boutain D, Schraufnagel TJ, Bumgardner K, Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne PP. Unmet need for mental health and addictions care in urban community health clinics: frontline provider accounts. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):505–11.

Cupples ME, Stewart MC, Percy A, Hepper P, Murphy C, Halliday HL. A RCT of peer-mentoring for first-time mothers in socially disadvantaged areas (the MOMENTS study). Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(3):252–8.

Day C, Michelson D, Thomson S, Penney C, Draper L. Evaluation of a peer led parenting intervention for disruptive behaviour problems in children: community based randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2012;344:e1107.

Dewey JM. Challenges of implementing collaborative models of decision making with trans-identified patients. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1508–18.

Dowrick C, Chew-Graham C, Lovell K. Increasing equity of access to high-quality mental health services in primary care: a mixed-methods study. NIHR J Libr Programm Grants Appl Res. 2013.

Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Hodder R, Wolfenden L, et al. Effectiveness of a pragmatic school-based universal intervention targeting student resilience protective factors in reducing mental health problems in adolescents. J Adolesc. 2017;57:74–89.

Eames C, Crane R, Gold E, Pratt S. Mindfulness-based wellbeing for socio-economically disadvantaged parents: a pre-post pilot study. J Child Apos. 2015;10(1):17–28.

Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Lattie EG, Lusarreta M, Marquine M, Vail M, et al. Managing depression among diverse older adults in primary care: the BRIGHTEN program. Clin Gerontol. 2017;40(2):88–96.

Galano MM, Grogan-Kaylor AC, Stein SF, Clark HM, Graham-Bermann SA. Posttraumatic stress disorder in Latina women: examining the efficacy of the moms’ empowerment program. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(3):344–51.

Gardner F, Connell A, Trentacosta CJ, Shaw DS, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Moderators of outcome in a brief family-centered intervention for preventing early problem behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol 2009;77(3):543–53.

Gardner F, Hutchings J, Bywater T, Whitaker C. Who benefits and how does it work? Moderators and mediators of outcome in an effectiveness trial of a parenting intervention. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2010;39(4):568–80.

Gilman SE, Fitzmaurice GM, Bruce ML, Ten Have T, Glymour MM, Carliner H, et al. Economic inequalities in the effectiveness of a primary care intervention for depression and suicidal ideation. Epidemiology. 2013;24(1):14–22.

Gonzales-Ball TL, Bratton SC. Child-teacher relationship training as a head start early mental health intervention for children exhibiting disruptive behavior. Int J Play Ther. 2019;28(1):44–56.

Gopalan G, Chacko A, Franco L, Dean-Assael KM, Rotko LE, Marcus SM, et al. Multiple family groups for children with disruptive behavior disorders: child outcomes at 6-month follow-up. J Child Fam Stud. 2015;24(9):2721–33.

Grote NK, Swartz HA, Geibel SL, Zuckoff A, Houck PR, Frank E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(3):313–21.

Grote NK, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Lohr MJ, Curran M, Galvin E, et al. Collaborative care for perinatal depression in socioeconomically disadvantaged women: a randomized trial. Depress Anxiety. 2015;32(11):821–34.

Grote NK, Katon WJ, Russo JE, Lohr MJ, Curran M, Galvin E, et al. A randomized trial of collaborative care for perinatal depression in socioeconomically disadvantaged women: the impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(11):1527–37.

Grote NK, Simon GE, Russo J, Lohr MJ, Carson K, Katon W. Incremental benefit-cost of MOMCare: collaborative care for perinatal depression among economically disadvantaged women. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(11):1164–71.

Habib N, Dawood S, Kingdon D, Naeem F. Preliminary evaluation of culturally adapted CBT for psychosis (CA-CBTp): findings from developing culturally-sensitive CBT project (DCCP). Behav Cogn Psychother. 2015;43(2):200–8.

Handley ED, Michl-Petzing LC, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Developmental cascade effects of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers: longitudinal associations with toddler attachment, temperament, and maternal parenting efficacy. Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29(2):601–15.

Harris LA. Therapeutic alliance factors in a sample of depressed Latinos receiving brief motivational interviewing. Diss Abstr Int. 2011;72(4):2436.

Held P, Owens GP. Effects of self-compassion workbook training on trauma-related guilt in a sample of homeless veterans: a pilot study. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(6):513–26.

Hess JM, Isakson B, Githinji A, Roche N, Vadnais K, Parker DP, et al. Reducing mental health disparities through transformative learning: a social change model with refugees and students. Psychol Serv. 2014;11(3):347–56.

Humayun S, Herlitz L, Chesnokov M, Doolan M, Landau S, Scott S. Randomized controlled trial of functional family therapy for offending and antisocial behavior in UK youth. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2017;58(9):1023–32.

Hutchings J, Griffith N, Bywater T, Williams ME. Evaluating the incredible years toddler parenting programme with parents of toddlers in disadvantaged (flying start) areas of Wales. Child Care Health Dev. 2017;43(1):104–13.

Jimenez DE, Begley A, Bartels SJ, Alegria M, Thomas SB, Quinn SC, et al. Improving health-related quality of life in older African American and non-Latino White patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2015;23(6):548–58.

Jongeneel-Grimen B, Droomers M, Kramer D, Bruggink JW, van Oers H, Kunst AE, et al. Impact of a Dutch urban regeneration programme on mental health trends: a quasi-experimental study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(10):967–73.

Kahalnik F, Sanchez K, Faria A, Grannemann B, Jha M, Tovian C, et al. Improving the identification and treatment of depression in low-income primary care clinics: a qualitative study of providers in the VitalSign6 program. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;4:04.

Katon W, Russo J, Reed SD, Croicu CA, Ludman E, LaRocco A, et al. A randomized trial of collaborative depression care in obstetrics and gynecology clinics: socioeconomic disadvantage and treatment response.[Erratum appears in Am J Psychiatry. 2015 Jan;172(1):100]. Am J Psychiatr. 2015;172(1):32–40.

Kenyon S, Jolly K, Hemming K, Hope L, Blissett J, Dann SA, et al. Lay support for pregnant women with social risk: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e009203.

Kuosmanen T, Fleming TM, Newell J, Barry MM. A pilot evaluation of the SPARX-R gaming intervention for preventing depression and improving wellbeing among adolescents in alternative education. Internet Interv. 2017;8:40–7.

Legrand FD. Effects of exercise on physical self-concept, global self-esteem, and depression in women of low socioeconomic status with elevated depressive symptoms. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2014;36(4):357–65.

Leijten P, Raaijmakers MA, Orobio de Castro B, van den Ban E, Matthys W. Effectiveness of the incredible years parenting program for families with socioeconomically disadvantaged and ethnic minority backgrounds. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(1):59–73.

Lovell K, Lamb J, Gask L, Bower P, Waheed W, Chew-Graham C, et al. Development and evaluation of culturally sensitive psychosocial interventions for under-served people in primary care. BMC Psychiatr. 2014;14:217.

Ludwig J, Duncan GJ, Gennetian LA, Katz LF, Kessler RC, Kling JR, et al. Neighborhood effects on the long-term well-being of low-income adults. Science. 2012;337(6101):1505–10.

Lwembe S, Green SA, Chigwende J, Ojwang T, Dennis R. Co-production as an approach to developing stakeholder partnerships to reduce mental health inequalities: an evaluation of a pilot service. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2017;18(1):14–23.

Mathias K, Pandey A, Armstrong G, Diksha P, Kermode M. Outcomes of a brief mental health and resilience pilot intervention for young women in an urban slum in Dehradun, North India: a quasi-experimental study. Int J Ment Heal Syst. 2018;12:47.

McGilloway S, Mhaille GN, Bywater T, Furlong M, Leckey Y, Kelly P, et al. A parenting intervention for childhood behavioral problems: a randomized controlled trial in disadvantaged community-based settings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):116–27.

McGilloway S, NiMhaille G, Bywater T, Leckey Y, Kelly P, Furlong M, et al. Reducing child conduct disordered behaviour and improving parent mental health in disadvantaged families: a 12-month follow-up and cost analysis of a parenting intervention. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(9):783–94.

Mehdipanah R, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Malmusi D, Muntaner C, Diez E, Bartoll X, et al. The effects of an urban renewal project on health and health inequalities: a quasi-experimental study in Barcelona. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(9):811–7.

Meir Y, Slone M, Levis M. A randomized controlled study of a group intervention program to enhance mental health of children of illegal migrant workers. Child Youth Care Forum. 2014;43(2):165–80.

Memon A, Taylor K, Mohebati LM, Sundin J, Cooper M, Scanlon T, et al. Perceived barriers to accessing mental health services among black and minority ethnic (BME) communities: a qualitative study in Southeast England. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11).

Mendelson T, Tandon SD, O’Brennan L, Leaf PJ, Ialongo NS. Brief report: moving prevention into schools: the impact of a trauma-informed school-based intervention. J Adolesc. 2015;43:142–7.

Meyers MA, Groh CJ, Binienda J. Depression screening and treatment in uninsured urban patients. JABFM. 2014;27(4):520–9.

Michelson D, Ben-Zion I, James AI, Draper L, Penney C, Day C. “Living with teenagers”: feasibility study of a peer-led parenting intervention for socially disadvantaged families with adolescent children. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(8):731–7.

Miech R, Azur M, Dusablon T, Jowers K, Goldstein AB, Stuart EA, et al. The potential to reduce mental health disparities through the comprehensive community mental health services for children and their families program. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2008;35(3):253–64.

O’Neill D, McGilloway S, Donnelly M, Bywater T, Kelly P. A cost-effectiveness analysis of the incredible years parenting programme in reducing childhood health inequalities. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(1):85–94.

Osok J, Kigamwa P, Huang KY, Grote N, Kumar M. Adversities and mental health needs of pregnant adolescents in Kenya: identifying interpersonal, practical, and cultural barriers to care. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):96.

Owiti JA, Ajaz A, Ascoli M, de Jongh B, Palinski A, Bhui KS. Cultural consultation as a model for training multidisciplinary mental healthcare professionals in cultural competence skills: preliminary results. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(9):814–26.

Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina H, Safren SA, Parsons JT. LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: a randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(5):875–89.

Pan D, Huey SJ Jr, Hernandez D. Culturally adapted versus standard exposure treatment for phobic Asian Americans: treatment efficacy, moderators, and predictors. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2011;17(1):11–22.

Pancer S, Nelson G, Hasford J, Loomis C. The better beginnings, better futures project: long-term parent, family, and community outcomes of a universal, comprehensive, community-based prevention approach for primary school children and their families. J Community Appl Soc Psychol. 2013;23(3):187–205.

Pearce MJ, Koenig HG. Spiritual struggles and religious cognitive behavioral therapy: a randomized clinical trial in those with depression and chronic medical illness. J Psychol Theol. 2016;44(1):3–15.

Peng S, Qi A, Yuan F. Experimental study on the effects of exercise prescription on the mental health of left-behind school children in rural areas. Rev Argent Clin Psicol. 2015;24(3):267–76.

Posselt M, McDonald K, Procter N, de Crespigny C, Galletly C. Improving the provision of services to young people from refugee backgrounds with comorbid mental health and substance use problems: addressing the barriers. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):280.

Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Ashori M, Jalilabkenar SS. The effectiveness of emotional intelligence training on the mental health of male deaf students. Iran J Public Health. 2013;42(10):1174–80.

Renner W, Banninger-Huber E, Peltzer K. Culture-sensitive and resource oriented peer (CROP)-groups as a community based intervention for trauma survivors: a randomized controlled pilot study with refugees and asylum seekers from Chechnya. Australas J Disaster Trauma Stud. 2011;2011(1):1–13.

Rhodes KV, Basseyn S, Gallop R, Noll E, Rothbard A, Crits-Christoph P. Pennsylvania’s medical home initiative: reductions in healthcare utilization and cost among medicaid patients with medical and psychiatric comorbidities. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(11):1373–81.

Roberts CM, Kane R, Bishop B, Cross D, Fenton J, Hart B. The prevention of anxiety and depression in children from disadvantaged schools. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48(1):68–73.

Romeo R, Knapp M, Morrison J, Melville C, Allan L, Finlayson J, et al. Cost estimation of a health-check intervention for adults with intellectual disabilities in the UK. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2009;53(5):426–39.

Sandner M, Cornelissen T, Jungmann T, Herrmann P. Evaluating the effects of a targeted home visiting program on maternal and child health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2018;58:269–83.

Seabra-Santos MJ, Gaspar MF, Major SO, Patras J, Azevedo AF, Homem TC, et al. Promoting mental health in disadvantaged preschoolers: a cluster randomized controlled trial of teacher training effects. J Child Fam Stud. 2018; No Pagination Specified.

Shaikh S, Mburu G, Arumugam V, Mattipalli N, Aher A, Mehta S, et al. Empowering communities and strengthening systems to improve transgender health: outcomes from the Pehchan programme in India. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(3):20809.

Sheeber LB, Seeley JR, Feil EG, Davis B, Sorensen E, Kosty DB, et al. Development and pilot evaluation of an internet-facilitated cognitive-behavioral intervention for maternal depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(5):739–49.

Sheeber LB, Feil EG, Seeley JR, Leve C, Gau JM, Davis B, et al. Mom-net: evaluation of an internet-facilitated cognitive behavioral intervention for low-income depressed mothers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(4):355–66.

Singh S, Islam Z, Brown L. Ethnicity, detention and early intervention: reducing inequalities and improving outcomes for black and minority ethnic patients: the ENRICH programme, a mixed-methods study. NIHR J Libr Programm Grants Appl Res. 2013.

Snowden LR, Wallace N, Cordell K, Graaf G. Increased medicaid financing and equalization of African Americans’ and Whites’ outpatient and emergency treatment expenditures. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2016;19(3):167–74.

Snowden LR, Wallace N, Cordell K, Graaf G. Increased mental health treatment financing, community-based organization’s treatment programs, and Latino-White children’s financing disparities. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2017;20(3):137–45.

Steinberg DM, Askew S, Lanpher MG, Foley PB, Levine EL, Bennett GG. The effect of a “maintain, don’t gain” approach to weight management on depression among black women: results from a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1766–73.

Stevens NR, Heath NM, Lillis TA, McMinn K, Tirone V, Sha’ini M. Examining the effectiveness of a coordinated perinatal mental health care model using an intersectional-feminist perspective. J Behav Med. 2018;41(5):627–40.

Stewart RW, Orengo-Aguayo RE, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, de Arellano MA. A pilot study of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy delivered via telehealth technology. Child Maltreat. 2017;22(4):324–33.

Sullivan G, Sherbourne C, Chavira DA, Craske MG, Gollineli D, Han X, et al. Does a quality improvement intervention for anxiety result in differential outcomes for lower-income patients? Am J Psychiatr. 2013;170(2):218–25.

Ter Heide FJ, Mooren TM, Kleijn W, de Jongh A, Kleber RJ. EMDR versus stabilisation in traumatised asylum seekers and refugees: results of a pilot study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2011;2.

Tighe J, Shand F, Ridani R, Mackinnon A, De La Mata N, Christensen H. Ibobbly mobile health intervention for suicide prevention in Australian indigenous youth: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013518.

Van der Gucht K, Takano K, Van Broeck N, Raes F. A mindfulness-based intervention for economically disadvantaged people: effects on symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression and on cognitive reactivity and overgeneralization. Mindfulness. 2015;6(5):1042–52.

van der Waerden JE, Hoefnagels C, Hosman CM, Souren PM, Jansen MW. A randomized controlled trial of combined exercise and psycho-education for low-SES women: short- and long-term outcomes in the reduction of stress and depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2013;91:84–93.

Velasquez AM, Lopez MA, Quinonez N, Paba DP. Yoga for the prevention of depression, anxiety, and aggression and the promotion of socio-emotional competencies in school-aged children. Educ Res Eval. 2015;21(5):407–21.

Walthery P, Stafford M, Nazroo J, Whitehead M, Dibben C, Halliday E, et al. Health trajectories in regeneration areas in England: the impact of the new deal for communities intervention. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(8):762–8.

Webster-Stratton C, Jamila Reid M, Stoolmiller M. Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: evaluation of the incredible years teacher and child training programs in high-risk schools. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008;49(5):471–88.

Weich S, Griffith L, Commander M, Bradby H, Sashidharan SP, Pemberton S, et al. Experiences of acute mental health care in an ethnically diverse inner city: qualitative interview study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47(1):119–28.

Weisman de Mamani A, Weintraub MJ, Gurak K, Maura J. A randomized clinical trial to test the efficacy of a family-focused, culturally informed therapy for schizophrenia. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28(6):800–10.

White J, Greene G, Farewell D, Dunstan F, Rodgers S, Lyons RA, et al. Improving mental health through the regeneration of deprived neighborhoods: a natural experiment. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186(4):473–80.

Williams KC, Falkum E, Martinsen EW. A cognitive therapy program for hearing-impaired employees suffering from mental distress. Int J Audiol. 2015;54(4):227–33.

Yahyaee M, Reza-Tajrishi MP, Sajedi F, Biglarian A. The effect of attribution retraining group program on depression of students with learning disabilities. Dev Psychol. 2014;10(39):263–74.

Zandkarimi G, Kamelifar L, Heshmati-Molaee N. Nonviolence communication to reduce stress, anxiety and depression in young iranian women: a randomized experiment. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2018:1–7.

Brown A, Rice SM, Rickwood DJ, Parker AG. Systematic review of barriers and facilitators to accessing and engaging with mental health care among at-risk young people. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2016;8(1):3–22.

De Vito E, de Waure C, Specchia ML, Parente P, Azzolini E, Frisicale EM, et al. Are undocumented migrants’ entitlements and barriers to healthcare a public health challenge for the European Union? Public Health Rev. 2016;37:13.

Bhui KS, Aslam RW, Palinski A, McCabe R, Johnson MR, Weich S, et al. Interventions to improve therapeutic communications between black and minority ethnic patients and professionals in psychiatric services: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(2):95–103.

Derr AS. Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: a systematic review. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(3):265–74.

Garcia ME, Ochoa-Frongia L, Moise N, Aguilera A, Fernandez A. Collaborative care for depression among patients with limited English proficiency: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):347–57.

Gardner F, Leijten P, Mann J, Landau S, Harris V, Beecham J, et al. Could scale-up of parenting programmes improve child disruptive behaviour and reduce social inequalities? Using individual participant data meta-analysis to establish for whom programmes are effective and cost-effective. NIHR J Libr. 2017;12:12.

Lamb J. Access to mental health in primary care: a qualitative meta-synthesis of evidence from the experience of people from “hard to reach” groups. Health (London). 2012;16(1):76–104.

Lucas PJ, McIntosh K, Petticrew M, Roberts H, Shiell A. Financial benefits for child health and well-being in low income or socially disadvantaged families in developed world countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;2:CD006358.

Pega F, Liu SY, Walter S, Pabayo R, Saith R, Lhachimi SK. Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011135.

Rojas-Garcia A, Ruiz-Perez I, Goncalves DC, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Ricci-Cabello I. Healthcare interventions for perinatal depression in socially disadvantaged women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2014;21(4):363–84.

Vallury KD, Jones M, Oosterbroek C. Computerized cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety and depression in rural areas: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e139.

van der Waerden JE, Hoefnagels C, Hosman CM. Psychosocial preventive interventions to reduce depressive symptoms in low-SES women at risk: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2011;128(1):10–23.

Weaver A, Lapidos A. Mental health interventions with community health workers in the United States: a systematic review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):159–80.

Inc A. Adobe illustrator [internet]: Adobe Inc.; 2020. Available from: https://adobe.com/products/illustrator.

Clarke AR, Goddu AP, Nocon RS, Stock NW, Chyr LC, Akuoko JAS, et al. Thirty years of disparities intervention research: what are we doing to close racial and ethnic gaps in health care? Med Care. 2013;51(11):1020–6.

Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, Seay KD. Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. J Subst Abus Treat. 2016;61:47–59.

Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manage Forum. 2017;30(2):111–6.

Ohtani A, Suzuki T, Takeuchi H, Uchida H. Language barriers and access to psychiatric care: a systematic review. PS. 2015;66(8):798–805.

Sambrook Smith M, Lawrence V, Sadler E, Easter A. Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e024803.

Wakida EK, Talib ZM, Akena D, Okello ES, Kinengyere A, Mindra A, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the integration of mental health services into primary health care: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):211.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sarah Dawson for her contributions to the development of the research questions and search strategy. They would also like to thank Dominique Gardner for her support in project managing this piece of work as part of the Advancing Mental Health Equality (AMHE) resource at the NCCMH. The authors also wish to acknowledge and thank all of the stakeholders involved in the development of the AMHE resource.

Funding

This review was funded by NHS England and commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as part of the Advancing Mental Health Equality resource, which was developed under the Mental Health Care Pathways programme at the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH). The publication charge for this article was paid for by the NCCMH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LLA contributed to research question design, screening and data extraction and led on the overall development and writing of this review. HG contributed to the writing of this review, particularly the development of definitions and criteria for inclusion, and created the mapping diagram. HB contributed to the screening and data extraction as well as the writing of this review. EK finalised the search strategy and performed the database searches. KT contributed to the writing of this review. SS provided oversight over the development of the review and contributed to definitions and inclusion criteria. CC contributed to the development of the review, particularly with regard to designing the research questions and the methods. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy.

Additional file 2.

Tabulated study characteristics for included primary studies.

Additional file 3.

Tabulated study characteristics for included systematic reviews.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arundell, LL., Greenwood, H., Baldwin, H. et al. Advancing mental health equality: a mapping review of interventions, economic evaluations and barriers and facilitators. Syst Rev 9, 115 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01333-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01333-6