Abstract

Background

Electronic health records (EHRs) are increasing in popularity across national and international healthcare systems. Despite their augmented availability and use, the quality of electronic health records is problematic. There are various reasons for poor documentation quality within the EHR, and efforts have been made to address these areas. Previous systematic reviews have assessed intervention effectiveness within the outpatient setting or within paper documentation. This systematic review aims to assess the effectiveness of different interventions seeking to improve EHR documentation within an inpatient setting.

Methods

We will employ a comprehensive search strategy that encompasses four distinct themes: EHR, documentation, interventions, and study design. Four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, and CINAHL) will be searched along with an in-depth examination of the grey literature and reference lists of relevant articles. A customized hybrid study quality assessment tool has been designed, integrating components of the Downs and Black and Newcastle-Ottawa Scales, into a REDCap data capture form to facilitate data extraction and analysis. Given the predicted high heterogeneity between studies, it may not be possible to standardize data for a quantitative comparison and meta-analysis. Thus, data will be synthesized in a narrative, semi-quantitative manner.

Discussion

This review will summarize the current level of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions implemented to improve inpatient EHR documentation, which could ultimately enhance data quality in administrative health databases.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42017083494

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

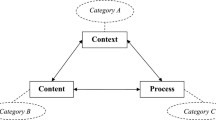

Healthcare professionals worldwide have transitioned from handwritten documentation to electronic reporting processes. In North America, over half of office-based practices and hospitals use some form of electronic health record (EHR) documentation [1]. Compared to conventional paper documentation, electronic health records produce clear, legible data that lends itself well to coders, computational analyses, and health service research. The administrative health record databases are fuelled by data produced by coders, who assign diagnostic codes to each diagnosis listed in patient charts. By removing the barrier of illegible or disorganized documentation, the quality of data in the administrative health record database is ameliorated. This data is then used for epidemiological studies, disease surveillance, and administrative and billing purposes [2]. Quality assurance of this data is thus crucial, and quality improvement strategies are being implemented at various points in the data management chain. As outlined in Fig. 1, this systematic review focuses on the quality of the data created during a clinical encounter, prior to its coding.

Because data quality is directly affected by the completion and accuracy of EHR documentation, it is important to assess and improve the quality of such documentation. Additionally, there has been a surge in research to improve EHR documentation due to the increase in medical errors associated with the use of EHRs [3]. Quality in EHRs may relate elements such as completeness, accuracy, clarity, and timeliness [4]. Although EHR documentation has existed since the 1960s, with the first computerized physician order entry system created in 1971 [5], a review of the medical literature reveals that the quality and usability of EHR documentation is generally poor [6]. Several problems with EHR documentation have been identified. These include structural problems where documentation quality suffers if the EHR system does not have built-in logic prohibiting the user from continuing onto the next section of documentation if the previous section has not been completed. Similarly, free-text fields, as opposed to point-and-click radio button documentation, have demonstrated increases in error [7]. Another common structural problem is the lack of standardization in EHR systems or vendors across all areas of healthcare delivery (i.e., outpatient versus inpatient EHR programs) [8]. In other instances, problems arise when EHR system users are not provided with adequate training and simply do not know how to use the system, leading to poor data quality. Resistance to EHR adoption further inhibits the standardization of documentation and can also impact data quality and usability [9].

Prior systematic reviews have explored ways to improve medical documentation; however, these were focused on the outpatient setting [10] or targeted EHR documentation of a specific EHR user [11]. Others failed to address electronic forms of documentation [12] or focused on a specific type of intervention to improve documentation [13, 14]. Noteworthy results from these systematic reviews illustrate the following: (1) a dearth of literature addressing EHR improvement, (2) successful interventions to improve EHR documentation (e.g., system add-ons, educational materials, and financial incentives), and (3) different indicators to measure quality of documentation, such as completeness and accuracy of patient information [10]. Using the PRISMA Protocol checklist, we outline our proposal for a systematic review of the literature to identify interventions, programs, or institutional changes (broadly referred to in this protocol as “interventions”) that have sought to improve EHR documentation in the inpatient setting and those that consequently may warrant implementation by EHR users [15].

Focused questions

Accordingly, the questions we are addressing are:

-

1.

What is the effectiveness of interventions seeking to improve inpatient hospital documentation in electronic health records?

It should be noted that the word “seeking” is crucial to this question; studies will be included in the review if the intent of the intervention was to improve documentation quality, regardless of the study outcome.

-

2.

What tools and metrics were used to measure the improvement in EHR documentation?

Methods

Search strategy

We will search the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and CINAHL, with no language or date restrictions. Additionally, both investigators (LOV and NW) will complete a grey literature search, including conference proceedings identified through EMBASE. Experts in the field, identified from the review process, and other researchers who have previously worked on the topic will be contacted for further information about ongoing or unpublished studies. Reference lists of included studies will also be searched.

After consulting with two librarians, the search strategy was organized into four exhaustive themes, resulting in four Boolean searches using the term “or” to explode and search by keyword different subject headings:

-

1.

Derivatives of “electronic health records” to specify the main outcome

-

2.

Derivatives of “documentation” to refine the main outcome

-

3.

Both general terms and specific examples of interventions, including synonyms or derivatives, to capture the vast array of interventions

Cochrane filter for randomized controlled trial (RCT), University of Alberta filter for observational studies, and PubMed Health filter for quasi-experimental studies to identify study designs [16,17,18]

Lastly, the Boolean operator “and” was used to combine the four search themes. An example of a detailed search strategy with all included terms is available in Additional file 1.

Improvement in documentation and its possible measures were not specified as search themes to avoid excluding studies that may have used an improvement measure not listed in the data extraction form. Further, since an intervention could be applied to the computer program or EHR “vendor,” rather than a human group of participants, EHR users were not specified in this search. An initial search in MEDLINE reveals approximately 1500 potential articles, with a similar result in EMBASE, indicating sufficient numbers to perform our analyses.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1. For the purpose of providing a comprehensive systematic review of the topic, we will not restrict this review to RCTs, but will incorporate all original literature reporting on the quality of EHR documentation. Consequently, experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational studies will be captured. The study population is primary users of inpatient EHRs, including physicians, nurses, diagnostic imaging staff, pharmacists, and clinical trainees (residents, interns, etc.). The interventions include but are not limited to activities, programs, or institutional changes applied to improve EHR documentation, such as the use of new software, dictation templates, audits, educational sessions, structured reporting, healthcare provider training, incentives, rewards, or penalties. Specifically, we will be looking for studies comparing interventions to controls (i.e., standard EHR documentation or a comparator intervention). The outcome of interest is improved EHR inpatient documentation, for which the measures have been identified from relevant literature and are further established by each individual study (Table 2).

Both abstract and full-text screening phases will be done independently by two reviewers (LOV and NW) with the support of an eligibility criteria screening tool (Table 3). Titles and abstracts will be scanned to select articles for in-depth analysis. Articles will be selected for full-text review if both reviewers agree on eligibility criteria or if the abstract does not provide sufficient information to make a decision. Any discrepancies between reviewers will be discussed until an agreement is reached. When necessary, additional clarity regarding article eligibility will be requested by contacting the articles’ authors and examining unclear articles with another investigator (DJN). Inter-rater agreement will be assessed using the kappa statistic for both stages of screening.

Data extraction and study quality assessment tool

REDCap was used to create a data extraction form with built-in logic to collect pertinent information from all included studies [19], available in Additional file 2. This logic also comprises hidden questions that appear when a certain answer is chosen. This feature is a “real-time” function that cannot be depicted in the printed form embedded as an additional file. The form focuses on the detailed study characteristics (e.g., EHR users, type of setting, outcome measures). For results of interventions, the reviewers will extract differences between intervention groups, as well as before and after, or cross-sectional designs. Results will be expressed as means, medians, proportions, or effect size, depending on the design. The data extraction tool will also allow reviewers to abstract the measure used to identify high- or low-quality EHR documentation. Study quality and systematic error (bias) will be assessed using a hybrid of the Downs and Black Scale and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, including 11 items to encompass experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational study designs (Additional file 3) [20, 21].

Data synthesis/analysis

Given the expected heterogeneity in methods and possibly in results in the extant literature, it is unclear if meta-analysis will be possible. We will explore the factors associated with heterogeneity and attempt to assess the effect of a number of variables on the results of the identified intervention. These variables include but are not limited to the type of EHR user (physician, nurse, pharmacist, therapist, etc.), type of setting (urban or rural), size of setting (single or multi-center) area of clinical practice, demographic characteristics of users, and experience with EHR (years of use). The final number and the characteristics of studies identified for inclusion in and exclusion from the systematic review will be reported in a PRISMA flow diagram. We will tabulate all extracted data, including participant characteristics, study designs, interventions, instruments, and study results. For the primary question (overall effectiveness of interventions), we will describe the range of results obtained across all studies, grouped by intervention. Differences between study results will be presented in a narrative form with semi-quantitative analysis, unless meta-analyses are feasible, as outlined above. To address the secondary question, we will describe the tools used to identify interventions with high or low effectiveness.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this will be the first systematic review to identify and evaluate interventions that are specifically aimed to improve EHR documentation in an inpatient setting.

The strengths of this systematic review include an in-depth search strategy, organized into four comprehensive themes; an elaborated eligibility criteria; and an adapted study quality assessment tool. Thus, this protocol provides a methodologically rigorous template for future similar systematic or scoping review studies for effective interventions.

Outcomes of this study will be applicable to clinicians, policy-makers, health information managers, quality improvement specialists, and coding organizations and will provide a direction for future researchers seeking to improve administrative discharge database quality.

Abbreviations

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EHR:

-

Electronic health record

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica dataBASE

- MEDLINE:

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- REDCap:

-

Research Electronic Data Capture

References

Maddox T, Matheny M. Natural language processing and the promise of big data. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:463–5.

Cadarette SM, Wong L. An introduction to health care administrative data. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2015;68(3):232–7.

Bowman, S. Impact of Electronic Health Record Systems on Information Integrity: Quality and Safety Implications. Perspectives in Health Information Management. 2013;10(Fall):1c.

Stetson PD, Bakken S, Wrenn JO, Siegler EL. Assessing electronic note quality using the Physician Documentation Quality Instrument (PDQI-9). Appl Clin Inform. 2012;3(02):164–74.

Doyle-Lindrud S. The evolution of the electronic health record. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(2):153–4.

Botsis T, Hartvigsen G, Chen F, Weng C. Secondary use of EHR: data quality issues and informatics opportunities. Summit Transl Bioinform. 2010;2010:1.

Dhavle AA, Corley ST, Rupp MT, et al. Evaluation of a user guidance reminder to improve the quality of electronic prescription messages. Appl Clin Inform. 2014;5(3):699–707.

O'leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, et al. Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):219–25.

Brailer DJ, Terasawa EL. Use and adoption of computer-based patient records. Calif HealthCare Found. 2003;1–42. https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-UseAdoptionComputerizedPatientRecords.pdf.

Hamade N. Improving the use of electronic medical records in primary health care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Western Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies: Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2017:4420. Available at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=6108&context=etd. Accessed 17 Oct 2017.

Lorenzetti D, Quan H, Lucyk K et al. Strategies for improving physician documentation in the emergency department: a systematic review. BMC Emerg Med. 2018;18(1):36.

Wang N, Hailey D, Yu P. Quality of nursing documentation and approaches to its evaluation: a mixed-method systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(9):1858–75.

Arditi C, Rège-Walther M, Durieux P, Burnand B. Computer-generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals, effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;7:CD001175.

Hyppönen H, Saranto K, Vuokko R, et al. Impacts of structuring the electronic health record: a systematic review protocol and results of previous reviews. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(3):159–69.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Metaanalysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):1.

Cochrane Handbook. Search strategies for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE. Accessed October 10th, 2017. http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/

BMJ Clinical Evidence. Study Design Search Filters. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/study-design-search-filters/. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

PubMed Health. Search strategies for the identification of clinical studies. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65481/. Accessed 10 Oct 2017.

Harris P, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Downs S, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in meta-analyses. 2011. Accessed October 2nd, 2017: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conceptualized by HQ. HLR, PER, LOV, and NW developed the search strategy. LOV and NW completed the search and drafted the protocol. DJN, PER, NI, and HQ critically appraised the protocol and also contributed to its development by revising subsequent versions. LOV and NW will contribute equally to the data collection and analysis, as well as the interpretation of the review. All authors critically revised the review and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consent and approve the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy for MEDLINE database. Accessed on November 8, 2017. (PDF 329 kb)

Additional file 2:

REDCap data extraction form. Data extraction form with built-in logic created with REDCap and used to collect relevant information from all included studies. (PDF 2243 kb)

Additional file 3:

Study quality assessment tool adapted from Downs and Black Scale combined with Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). Eleven-item hybrid of Downs and Black and Newcastle-Ottawa Scales, used to assess study quality and systematic error (bias) of selected studies, encompassing experimental, quasi-experimental, and observational study designs. (PDF 644 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Otero Varela, L., Wiebe, N., Niven, D.J. et al. Evaluation of interventions to improve electronic health record documentation within the inpatient setting: a protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev 8, 54 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-0971-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-0971-2