Abstract

Systemic administration of γ-amino-butyric acid type A (GABA-A) and benzodiazepine receptor agonists has been reported to block the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine. Here, we investigated whether the non-anesthetic noble gas argon, shown to possess agonistic properties at these receptors, may block the acquisition of amphetamine-induced locomotor sensitization and mu opioid receptor activation in the nucleus accumbens. Rats were pretreated with saline solution or amphetamine (1 mg/kg) from day 1 to day 3 and then exposed, immediately after injection of amphetamine, to medicinal air or argon at 75 vol% (with the remainder being oxygen). After a 3-day period of withdrawal, rats were challenged with amphetamine on day 7. Rats pretreated with amphetamine and argon had lower locomotor activity (U = 5, P < 0.005) and mu opioid receptor activity in the nucleus accumbens (U = 0, P < 0.001) than rats pretreated with amphetamine and air. In contrast, argon had effect on locomotor and mu receptor activity neither in rats pretreated with saline and challenged with amphetamine (acute amphetamine) nor in rats pretreated and challenged with saline solution (controls). These results indicate that argon inhibits the development of both locomotor sensitization and mu opioid receptor activation induced by repeated administration of amphetamine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, a series of in vitro and in vivo studies has demonstrated the organoprotective and therapeutic potential of the inert gases xenon, nitrous oxide, and argon [1]-[13]. Particularly, in line with their antagonistic action at the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor and nicotinic acetylcholine (nACh) receptor [14]-[19], xenon and nitrous oxide at subanesthetic doses have been shown to block the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine [20], which is characterized by an enhanced locomotor response to an amphetamine challenge in rats pretreated with repeated amphetamine. So far, in contrast with xenon and nitrous oxide, the non-anesthetic gas argon is thought to act mainly through activation of the γ-amino-butyric acid (GABA) type A and benzodiazepine receptors [21]. Although GABA-A and benzodiazepine receptor agonists have been shown to block the acquisition of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine and amphetamine-derived drugs [22],[23], whether argon may also inhibit the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine still remains unknown.

Therefore, in the present study, we investigated the effect of argon on the development of amphetamine-induced locomotor sensitization and mu opioid receptor activation the nucleus accumbens, whose elevated activity has been shown to be critically involved in the development of neurobehavioral sensitization to amphetamine [24]-[27].

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal-use procedures were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and within the framework of the French legislation for the use of animals in biomedical experimentation, and were approved by a research ethic committee. Male adult Sprague–Dawley rats (Janvier, Le Genest Saint-Isle, France) weighing 250 to 300 g were used. Rats were housed socially at 21.5°C in groups of 3 to 4 in perspex home cages with free access to food and water. Light was maintained on a reverse light–dark cycle, with lights on from 8 PM to 8 AM.

Sensitization to amphetamine

Rats (n = 8 per group) were treated daily with either amphetamine (1 mg/mL/kg, intraperitoneally; IP) or saline solution (1 mL/kg, IP) from day 1 to day 3. Immediately after injection of amphetamine or saline solution, rats were treated for 3 h with “medicinal” air (composed of 75 vol% nitrogen + 25 vol% oxygen) or with argon at 75 vol% (with the remainder being oxygen). Then, after 3 days of withdrawal, behavioral and neurochemical investigations were performed as detailed below (Figure 1). Both gas mixtures were administered at a flow rate of 5 L/min in a closed chamber of 100 L volume (65 × 45 × 35 cm), a condition that allows maintaining carbon dioxide less than 0.03 vol% and humidity about 65-70% inside the chamber with the use of soda lime and silica gel, respectively.

Experimental protocol and procedures. Rats (n = 8 per group) were treated daily with either saline solution (1 mL/kg intraperitoneally; IP) or amphetamine (1 mg/mL/kg, IP) from day 1 to day 3. Immediately after injection of saline solution or amphetamine, rats were treated for 3 h with “medicinal” air (composed of 75 vol% nitrogen + 25 vol% oxygen) or argon at 75 vol% (with the remainder being oxygen). Then, after 3 days of withdrawal, behavioral investigations were performed on day 7. Immediately after behavioral testing, the rats’ brain were removed and used to assess the constitutive activity of the mu opioid receptor in the nucleus accumbens.

Behavioral investigations

On day 7, rats were habituated to the activity boxes for 1 h before being challenged with saline solution (1 mL/kg, IP) or amphetamine (1 mg/mL/kg, IP), and then were recorded for locomotor activity for 1 h 30 min as detailed previously [21]. Locomotor activity was quantified using a bank of 4 individual activity cages measuring 30 × 20 × 20 cm, equipped with horizontal infrared beams, located 3 cm above the floor across the long axis of the cage (Imetronic, Pessac, France). Beam interruptions were detected through an electrical interface and recorded over 10-min intervals. All experiments were performed during the animals’ dark cycle with the activity boxes kept dark.

Neurochemical assays

Immediately after amphetamine challenge on day 7, rats were killed and their brain was carefully removed from their skull, frozen with isopentane and then stored at −20°C. For each animal, two coronal sections of 20 μm thickness including the nucleus accumbens (anteriority: +1 mm from the bregma) were cryostat cut, applied to glass slides with a very low non-specific binding capacity (Superfrost Plus, Menzel-Glaser GmbH, Braunscheig, Germany) and stored at -20°C until required for the binding assays.

Saturation binding was performed on rat brain sections as detailed previously [28]. Brain sections were preincubated twice for 5 min at 4°C in 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer solution [(hydroxyl-methyl)aminomethane] containing 100 mM NaCl, 1 g/L bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 20 mg/L bacitracin, adjusted to pH 7.4, in order to dissociate and eliminate potential endogenous ligands. Then, brain sections were incubated for 45 min at 4°C using 800 μL of buffer solution containing increasing concentrations (0.312, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5 nM) of [3H]DAMGO [(D-ala2,N-methyl-phe4,glycol5)(tyrosyl-3,5-3H)enkephalin, 1 Ci/L, specific radioactivity 66 Ci/mmol]. The amount of non-specific labelling was assessed using adjacent brain sections in the presence of an excess of naloxone at 10 μM. After incubation, brain sections were quickly washed (30 s) with Tris–HCl buffer containing BSA (x1) and then with Tris–HCl buffer alone (x3) at 4°C in order to eliminate unbound ligand. A final wash was performed at 4°C with distilled water to remove excess of buffer salts. Then, brain sections were dried over night at room temperature and stored until counting. Before being used for image acquisition and data analysis, slides containing brain sections were exposed under tritium-sensitive phosphor screens in the dark for 10 days at −20°C. Images were then captured with a computer-controlled Cyclone phosphorimaging scanner using the OptiQuant acquisition and analysis software (Packard Instrument Company, Meriden, CT, USA). Optical densities expressed as digital light units per mm2 over [3H] standard spot were measured. Specific binding was determined by subtracting non-specific binding from total binding. Saturation binding data were fitted according to a one site binding (hyperbola) model using Graph Pad prism (Graph Pad Prism 4.02; Graph Pad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The ratio of changes in percentage from basal values of the maximal number of binding sites (Bmax in fmol/mm3) to the dissociation constant (Kd in nM) was calculated by the computer to assess the level of constitutive activity of the mu opioid receptor in the nucleus accumbens in the presence of amphetamine and/or argon.

Drugs, chemical, and gases

Amphetamine (d-amphetamine hemisulfate salt, ref. A5880), BSA (bovine serum albumin ref. 2153), and naloxone (Naloxone hydrochloride dihydrate, ref. N7758) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Illkirch, France). Bacitracin was purchased from MP biomedicals (Santa Ana, CA, USA), and [3H]DAMGO (66 Ci/mmol) from Amersham Biosciences (Buckinghamshire, UK). Oxygen, nitrogen and argon of medicinal grade were purchased from Air Liquide (Paris, France). Gas mixtures composed of 75 vol% nitrogen + 25 vol% oxygen or 75 vol% argon + 25 vol% oxygen were obtained using calibrated flowmeters and gas analysers.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the median and quartiles values, and analyzed using non-parametric statistical methods. Between-group comparisons were performed using the Kruskall-Wallis analysis of variance; following a significant H value, post hoc analysis was performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Amphetamine-induced changes in locomotor activity and Mu receptor activity

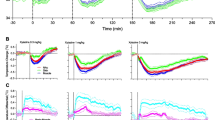

The effects of amphetamine on locomotor activity and mu receptor activity are illustrated in Figure 2. All rats were pretreated with either saline solution or amphetamine and then exposed immediately to medicinal air used as a control gas treatment. When challenged with amphetamine, rats pretreated with repeated administration of saline solution or amphetamine had higher scores of locomotor activity than control rats pretreated and challenged with saline solution (U = 1, P = 0.001, Figure 2B). Further comparison between rats challenged with amphetamine showed that rats pretreated with repeated administration of amphetamine had higher scores of locomotor activity than rats pretreated with saline (U = 0, P < 0.001, Figure 2A), indicating that locomotor sensitization to amphetamine had occurred.

Effects of amphetamine on locomotor activity and mu receptor activity in the nucleus accumbens. (A) When challenged with amphetamine, rats pretreated with repeated administration of saline solution (SA) or amphetamine (AA) had higher locomotor responses than rats pretreated and challenged with saline solution (SS). Locomotor activity is expressed in arbitrary units. (B) As assessed immediately after being challenged with amphetamine, rats pretreated with repeated injection of saline solution (SA) or amphetamine (AA) had higher mu receptor activity in the nucleus accumbens than rats pretreated and challenged with saline solution (SS). The ratio of the dissociation constant (Kd) to the maximal number of binding sites (Bmax) was calculated to assess the activity of mu receptors in the nucleus accumbens; mu receptor activity in controls rats pretreated and challenged with amphetamine was taken as a 100 % value. SS: pretreatment with saline + challenge with saline; SA: pretreatment with saline + challenge with amphetamine; AA: pretreatment with amphetamine + challenge with amphetamine. * P < 0.001 vs SS + Air; #P < 0.001 vs SA + Air.

As assessed immediately after the amphetamine challenge, rats pretreated with repeated administration of saline solution or amphetamine had increased mu receptor activity as estimated by the ratio of Bmax to Kd compared to control rats pretreated and challenged with saline solution (U = 4, P = 0.005; U = 0, P < 0.001; Figure 2B). However, in contrast with what seen for locomotor activity, further comparison between rats challenged with amphetamine revealed no significant difference in mu receptor activity between rats pretreated with repeated administration of amphetamine and those pretreated with repeated administration of saline solution and medicinal air (U = 32, n.s., Figure 2B).

Effects of argon on amphetamine-induced changes

The effects of argon on locomotor sensitization and changes in mu receptor activity induced by repeated administration of amphetamine are illustrated in Figure 2. Exposure to argon, immediately after administration of amphetamine, blocked the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine. Indeed, when challenged with amphetamine, rats pretreated with amphetamine and argon had lower locomotor activity than control rats pretreated with amphetamine and air (U = 5, P < 0.005; Figure 3A). In contrast with its inhibitory effect on the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine, argon had significant effect neither on the locomotor-activating action of acute amphetamine nor on basal locomotor activity (Figure 3A). Indeed, when challenged with amphetamine, rats pretreated with saline solution and argon had locomotor activity that was not different from that displayed by rats pretreated with saline solution and air (U = 20, n.s.). Likewise, when challenged with saline solution, rats pretreated with saline solution and argon had locomotor activity that was not different from that displayed by rats pretreated with saline solution and air (U = 17.5, n.s.).

Effects of argon on amphetamine-induced changes in locomotor activity and mu receptor activity in the nucleus accumbens. (A) When challenged with amphetamine, rats pretreated with amphetamine and argon had lower locomotor activity than rats pretreated with amphetamine and air (AA); in contrast, no significant difference in locomotor activity was found between rats pretreated with saline and argon and those pretreated with saline and air when challenged with amphetamine (SA) or saline (SS). This indicates that argon blocked locomotor sensitization to amphetamine, but had effect neither on locomotor activity induced by acute amphetamine nor on basal locomotor activity. Locomotor activity is expressed in arbitrary units. (B) As assessed immediately after being challenged with amphetamine, rats pretreated with amphetamine and argon had reduced mu receptor activity compared to rats pretreated with amphetamine and air (AA); in contrast, no significant difference in mu receptor activity was found between rats pretreated with saline and argon and those pretreated with saline and air when challenged with amphetamine (SA) or saline (SS). This indicates that argon blocked the increase in mu receptor activity induced by repeated amphetamine, but had effect neither on the increase in mu receptor activity induced by acute amphetamine nor on basal mu receptor activity. The ratio of the dissociation constant (Kd) to the maximal number of binding sites (Bmax) was calculated to assess the activity of mu receptors in the nucleus accumbens; mu receptor activity in controls rats pretreated and challenged with amphetamine was taken as a 100 % value. SS: pretreatment with saline + challenge with saline; SA: pretreatment with saline + challenge with saline; AA: pretreatment with amphetamine + challenge with amphetamine. * P < 0.001 vs AA + Air.

Exposure to argon immediately after amphetamine administration blocked the increase in mu receptor activity induced by repeated administration of amphetamine, so that, as assessed immediately after the amphetamine challenge, rats pretreated with amphetamine and argon had reduced mu receptor activity compared to rats pretreated with amphetamine and air (U = 0, P = 0.001, Figure 3B). In contrast, argon had no significant effect on mu receptor activity in rats pretreated with saline and air and challenged with amphetamine (acute amphetamine; U = 32, n.s., Figure 3B), or in control rats pretreated and challenged with saline (U = 19, n.s., Figure 3B).

Discussion

In the present study, we showed that argon inhibited the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine, but had effect neither on the locomotor activating properties of acute amphetamine nor on basal locomotor activity. In addition, we found that argon further blocked the increase in mu receptor activity induced by repeated administration of amphetamine, but had effect neither on the increase in mu receptor activity induced by acute amphetamine nor on basal mu receptor activity in the nucleus accumbens. Taken together, these results show that argon “specifically” inhibits both locomotor sensitization and the increase in mu receptor activity induced by repeated amphetamine administration.

The mu opioid neurotransmission is an integral part of the motive circuit and as such it is well recognized to be fully involved in the mechanisms of action and the behavioral effects of drugs that belong to the amphetamine family [27]. Thus, rats subjected to repeated administration of amphetamine have been demonstrated to exhibit enhanced responsiveness and elevated constitutive activity of mu opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens [29], and knock-out mice lacking the mu receptor have been shown to be insensitive to behavioral sensitization induced by amphetamine-derived drugs [26]. Interestingly, other investigations have shown that the GABA-A and mu receptors are closely linked. In that way, previous studies have demonstrated that blocking the mu receptor by specific antagonists allows inhibiting behavioral responses elicited by focal injection of GABA-A receptor agonists in the nucleus accumbens [30]. Also, mu-opioid receptor knockout mice have been reported to show increased binding for [3H]GABA-A agonists in the cortex and hippocampus compared to wild-type mice [31]. Therefore, whether argon inhibits the enhanced constitutive activity of mu receptors induced by repeated administration of amphetamine directly through competitive or non-competitive antagonism of the mu opioid receptor or indirectly through its agonistic action at the GABA-A receptor [21], still remains to be elucidated, particularly if one considers that the administration of prototypical GABA-A and benzodiazepine receptor agonists has been reported to block the acquisition of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine [22],[23].

Inert gases are well-known to act at multiple targets. For instance, xenon and nitrous oxide have antagonistic properties at the NMDA glutamate and nACh acetylcholine receptors and, on the contrary, possess agonistic action at the two-pore domain TREK-1 potassium channel [15],[16],[32]. The present study suggests that argon could act as a mu receptor antagonist in addition of its agonistic properties at the GABA-A receptor [21]. These latter effects could both participate to the inhibiting action of argon at blocking locomotor sensitization to amphetamine [22],[23],[26],[33]. Further in vitro experiments should be performed to investigate the way by which argon modulates the mu opioid receptor, directly or indirectly through activation of the GABA-A receptor. Whatever, our results clearly demonstrate that argon down regulates the activity of the mu opioid receptor and that it may have beneficial effect on the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine, a condition necessary for actually evaluating the potential of argon as a possible therapeutic agent in the treatment of drug addiction.

If argon would act as a direct inhibitor of the mu opioid receptor, its therapeutic potential could be of interest in other, mainly psychiatric, diseases such as depression, stress-induced disorders, attentional and hyperactivity disorders, and impulse control disorders.

References

David HN, Léveillé F, Chazalviel L, MacKenzie ET, Buisson A, Lemaire M, Abraini JH: Reduction of ischemic brain damage by nitrous oxide and xenon. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003, 23: 1168-1173. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000087342.31689.18.

David HN, Haelewyn B, Rouillon C, Lecocq M, Chazalviel L, Apiou G, Risso JJ, Lemaire M, Abraini JH: Neuroprotective effects of xenon: a therapeutic window of opportunity in rats subjected to transient cerebral ischemia. FASEB J. 2008, 22: 1275-1286. 10.1096/fj.07-9420com.

David HN, Haelewyn B, Degoulet M, Colomb DG, Risso JJ, Abraini JH: Ex vivo and in vivo neuroprotection induced by argon when given after an excitotoxic or ischemic insult. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e30934-10.1371/journal.pone.0030934.

Homi HM, Yokoo N, Ma D, Warner DS, Franks NP, Maze M, Grocott HP: The neuroprotective effect of xenon administration during transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Anesthesiology. 2003, 99: 876-881. 10.1097/00000542-200310000-00020.

Ma D, Yang H, Lynch J, Franks NP, Maze M, Grocott HP: Xenon attenuates cardiopulmonary bypass-induced neurologic and neurocognitive dysfunction in the rat. Anesthesiol. 2003, 98: 690-698. 10.1097/00000542-200303000-00017.

Yarin YM, Amarjargal N, Fuchs J, Haupt H, Mazurel B, Morozovan SV, Gross J: Argon protects hypoxia-, cisplatin- and gentamycin-exposed hair cells in the newborn rat’s organ of Corti. Hear Res. 2005, 201: 1-9. 10.1016/j.heares.2004.09.015.

Abraini JH, Lemaire M, David HN: Potentially neuroprotective and therapeutic properties of nitrous oxide and xenon. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005, 1053: 289-300. 10.1196/annals.1344.025.

Dingley J, Tooley J, Porter H, Thoresen M: Xenon provides short-term neuroprotection in neonatal rats when administered after hypoxia-ischemia. Stroke. 2006, 37: 501-506. 10.1161/01.STR.0000198867.31134.ac.

Pagel PS, Krolikowski JG, Shim YH, Venkatapuram S, Kersten JR, Weihrauch D, Warltier DC, Pratt PF: Noble gases without anesthetic properties protect myocardium against infarction by activating prosurvival signalling kinases and inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition in vivo. Anesth Analg. 2007, 105: 562-569. 10.1213/01.ane.0000278083.31991.36.

Haelewyn B, David HN, Rouillon C, Chazalviel L, Lecocq M, Risso JJ, Lemaire M, Abraini JH: Neuroprotection by nitrous oxide: facts and evidence. Crit Care Med. 2008, 36: 2651-2659. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318183f646.

Jawad N, Rizvi M, Gu J, Adeyi O, Tao G, Maze M, Ma D: Neuroprotection (and lack of neuroprotection) afforded by a series of noble gases in an in vitro model of neuronal injury. Neurosci Lett. 2009, 460: 232-236. 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.05.069.

Loetscher PD, Rossaint J, Rossaint R, Weis J, Fries M, Fahlenkamp A, Ryang YM, Grottke O, Argon MC: Neuroprotection in in vitro models of cerebral ischemia and traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2009, 13: R206-10.1186/cc8214.

Zhuang L, Yang T, Zhao H, Fidalgo AR, Vizcaychipi MP, Sanders RD, Yu B, Takata M, Johnson MR, Ma D: The protective profile of argon, helium, and xenon in a model of neonatal asphyxia in rats. Crit Care Med. 2012, 40: 1724-1730. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182452164.

Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM, Mennerick S, Powell S, Dikranian K, Benshoff N, Zorumski CF, Olney JW: Nitrous oxide (laughing gas) is an NMDA antagonist, neuroprotectant and neurotoxin. Nature Med. 1998, 4: 460-463. 10.1038/nm0498-460.

Franks NP, Dickinson R, de Sousa SLM, Hall AC, Lieb WR: How does xenon produce anesthesia?. Nature. 1998, 396: 324-10.1038/24525.

Yamakura T, Harris RA: Effects of gaseous anesthetics nitrous oxide and xenon on ligand-gated ion channels. Comparison with isoflurane and ethanol. Anesthesiology. 2000, 93: 1095-1101. 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00034.

Northrop NA, Smith LP, Yamamoto BK, Eyerman DJ: Regulation of glutamate release by α7 nicotinic receptors: differential role in methamphetamine-induced damage to dopaminergic and serotonergic terminals. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011, 336: 900-907. 10.1124/jpet.110.177287.

Kim MN, Jutkiewicz EM, Zhang M, Gnegy ME: The sensitizing effect of acute nicotine on amphetamine-stimulated behavior and dopamine efflux requires activation of β2 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 2011, 60: 1126-1134. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.003.

Degoulet M, Rostain JC, Abraini JH, David HN: Short-term development of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine requires N-methyl-D-aspartate- and nicotinic-dependent mechanisms in the nucleus accumbens. Addict Biol. 2013, 18: 417-424. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00297.x.

David HN, Ansseau M, Lemaire M, Abraini JH: Nitrous oxide and xenon prevent amphetamine-induced carrier-mediated dopamine release in a memantine-like fashion and protect against behavioral sensitization. Biol Psych. 2006, 60: 49-57. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.007.

Abraini JH, Kriem B, Balon N, Rostain JC, Risso JJ: Gamma-aminobutyric neuropharmacological investigations on narcosis produced by nitrogen, argon, or nitrous oxide. Anesth Analg. 2003, 96: 746-749. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000050282.14291.38.

Ito K: The role of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-benzodiazepine neurotransmission in an animal model of methamphetamine-induced psychosis. Hokkaido Igaku Zasshi. 1999, 74: 135-144.

Ito K, Ohmori T, Abekawa T, Koyama T: The role of benzodiazepine receptors in the acquisition and expression of behavioral sensitization to methamphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000, 65: 705-710. 10.1016/S0091-3057(99)00263-4.

Hyman SE: Addiction to cocaine and amphetamine. Neuron. 1996, 16: 901-904. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80111-7.

Everitt B, Wolf ME: Psychomotor stimulant addiction: a neural systems perspective. J Neurosci. 2002, 22: 3312-20.

Shen X, Purser C, Tien LT, Chiu CT, Paul IA, Baker R, Loh HH, Ho IK, Ma T: mu-Opioid receptor knockout mice are insensitive to methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization. J Neurosci Res. 2010, 88: 2294-302. 10.1002/jnr.22386.

Tien LT, Ho IK: Involvement of μ-Opioid Receptor in Methamphetamine-Induced Behavioral Sensitization. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2011, 9: 215-8. 10.2174/157015911795016949.

Poisnel G, Dhilly M, Le Boisselier R, Barre L, Debruyne D: Comparison of five benzodiazepine-receptor agonists on buprenorphine-induced mu-opioid receptor regulation. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009, 110: 36-46. 10.1254/jphs.08249FP.

Chiu CT, Ma T, Ho IK: Methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice: alterations in mu-opioid receptor. J Biomed Sci. 2006, 13: 797-811. 10.1007/s11373-006-9102-x.

Khaimova E, Kandov Y, Israel Y, Cataldo G, Hadjimarkou MM, Bodnar RJ: Opioid receptor subtype antagonists differentially alter GABA agonist-induced feeding elicited from either the nucleus accumbens shell or ventral tegmental area regions in rats. Brain Res. 2004, 1026: 284-94. 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.08.032.

Tien LT, Ma T, Fan LW, Loh HH, Ho IK: Autoradiographic analysis of GABAA receptors in mu-opioid receptor knockout mice. Neurochem Res. 2007, 32: 1891-7. 10.1007/s11064-007-9373-2.

Gruss M, Bushell TJ, Bright DP, Lieb WR, Mathie A, Franks NP: Two-pore-domain K+ channels are a novel target for the anesthetic gases xenon, nitrous oxide, and cyclopropane. Mol Pharmacol. 2004, 65: 443-52. 10.1124/mol.65.2.443.

Chen JC, Liang KW, Huang EY: Differential effects of endomorphin-1 and −2 on amphetamine sensitization: neurochemical and behavioral aspects. Synapse. 2001, 39: 239-48. 10.1002/1098-2396(20010301)39:3<239::AID-SYN1005>3.0.CO;2-B.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Centre de recherche Hôtel-Dieu de Lévis (QC, Canada), NNOXe Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Quebec, canada), Air Liquide (Paris, France), and the Université de Caen and the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique – CNRS (France).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

HND was paid scientist at NNOXe Pharmaceuticals, Québec, Canada. ML is medical director at Air Liquide, Paris, France. Both companies, NNOXe Pharmaceuticals and Air Liquide, have patents on the use of argon as a medical gas.

Authors’ contributions

HND, MD(2), NV, JEB, JJR, and JHA designed the study. HND and MD(2) carried out the drug treatment protocol and the behavioral experiments. HND, MD(1), and GP carried out the biochemical assays. HND, CM, NV, JEB, JJR, DD, and JHA wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

David, H.N., Dhilly, M., Poisnel, G. et al. Argon prevents the development of locomotor sensitization to amphetamine and amphetamine-induced changes in mu opioid receptor in the nucleus accumbens. Med Gas Res 4, 21 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13618-014-0021-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13618-014-0021-z