Abstract

Severe and recurrent infections of the respiratory tract in early childhood constitute major risk factors for the development of bronchial hyper-responsiveness and obstructive respiratory diseases in later life. In the first years of life, the vast majority of respiratory tract infections (RTI) leading to wheezing and asthma are of a viral origin and severity and recurrence are the consequence of a greater exposure to infectious agents in a period when the immune system is still relatively immature. Therefore, boosting the efficiency of the host immune response against viral infections seems to be a rational preventative approach. In the last decades it has been demonstrated that living in farm environments, i.e. early-life exposure to microbes, may reduce the risk of allergic and infectious disorders, increasing the immune response efficacy. These findings have suggested that treatment with bacterial lysates could promote a nonspecific immunomodulation useful in the prevention of recurrent RTIs and of wheezing inception and persistence. Experimental and clinical studies showing the reduction of RTI frequency and severity in childhood and elucidating the involved mechanisms can support this hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Respiratory tract infections (RTI) are amongst the leading causes of childhood morbidity and mortality globally [1, 2]. Viruses, and less often bacteria, are involved in the pathogenesis and frequently the etiology is mixed [3, 4]. Most children with recurrent RTI are otherwise healthy and the respiratory recurrences are the consequence of increased early life exposure to infectious agents, prior to full maturation of the immune system [5,6,7]. Most acute RTI are self-limiting, but often recur and are associated with respiratory sequelae, most commonly airway hyper-responsiveness, wheezing and ultimately asthma [7,8,9]. International guidelines for prevention or treatment of these highly prevalent clinical problems are scanty [10]. Over the last decades, attempts have been made to reduce post-infectious respiratory symptoms and morbidity by using inhaled corticosteroids or leukotriene receptor antagonists, but no disease-modifying effects have been documented [11, 12]. It was, however, observed that living in farming communities may increase the efficiency of the immune responses, not only against allergens but possibly also against infectious pathogens [13]. The evidence that early-life exposure to microbes may have protective effects has suggested that prebiotics, probiotics, and bacterial lysates could prevent the onset of wheezing and asthma through “nonspecific immunomodulation” of the body’s natural defenses [14] and reduce virus-induced wheezing exacerbations [15]. It has been even hypothesized that oral bacterial lysates (OBL) may promote a re-organization not only of the gut but also of the lung microbiota thus favouring the immune homeostasis via the gut-lung axis [16] This is an area of future research, identified also by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute roadmap, to provide potential targets of intervention in the primary prevention of chronic lung diseases [17]. In the present review, we will summarize and discuss the available data on how pharmaceutical products containing bacterial antigens can modulate the host immune response in children and could represent a valuable option in the prevention of recurrent RTI, in instances attributable to a viral origin. Early evidence suggests that bacterial lysates might play a role in reducing the risk of recurrent wheeze and possibly of asthma inception filling a gap in this area of unmet high medical need.

Viral infections, wheezing and asthma

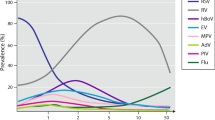

Structural and functional changes induced by respiratory viral infections in the airways during early childhood may promote self-perpetuating inflammatory mechanisms and, in predisposed individuals, a selection towards a Th2-type response that can lead to wheezing and asthma. Highly sensitive and specific tests, such as polymerase chain reaction, have been developed in the past few decades, allowing accurate detection of viruses associated with acute and recurrent wheezing illness [15, 18, 19]. This has led to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of these disorders as well as the features of the innate and adaptive immune response, here summarized, that can be modulated by therapeutics such as bacterial lysates. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and human rhinovirus (HRV) top the list of viruses involved in the pathogenesis, but enterovirus, human metapneumovirus, bocavirus and coronavirus also play a role [15, 18,19,20,21,22]. In particular, the recent SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus pandemic made us aware of possible serious public health consequences associated with infection with a respiratory virus apparently relatively benign in children but possibly devastating when being spread out to adults [23]. All these respiratory viruses target airway epithelial cells [3, 15, 20]. Viral adhesion to the epithelial cell membrane is followed by infection, viral replication, virion shedding/budding into the airway lumen and infection of neighboring cells [19, 20]. Recognition of viral transcripts and replication intermediates by host cells induces production of cytokines and chemokines, aimed at mounting an effective early antiviral response. In the first days of the infection, recruited natural killer (NK) cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes eliminate the infected epithelial cells, limiting viral replication and spread [20, 23]. The resulting epithelial damage is associated with bronchial inflammation and hyperresponsiveness [24]. Respiratory viruses also infect and/or are recognized by airway dendritic cells (DCs) that migrate to regional lymphoid tissues and present viral antigens to naïve T-cells [20, 21, 25,26,27]. Depending on the immunological environment, naïve T-cells differentiate into Th1 or Th2 cells. Th1 cell polarization promotes interferon-(IFN)-γ production with activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells and NK cells to clear viruses and the infected host cells by direct cytolysis. In contrast, Th2 cell polarization results in an inefficient immune response, increased disease severity and risk for future recurrent wheezing [25]. Upon contact with antigen-presenting cells, macrophage activities are also stimulated, and B-lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation induced, with production of antigen-specific IgM, IgG, and IgA. Two other T-lymphocyte populations, derived from naïve CD4+ T-cells, are involved in the response to viral infection: regulatory T-cells (Treg) and interleukin IL-17-producing T helper cells (Th17). Treg cells are involved in promotion of viral clearance as well as modulation of many aspects of the innate and adaptive immune responses. These include activation of neutrophils and NK cells, early recruitment of CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells, but also prevention of an excessive antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell response and, importantly, limitation of inefficient Th2-type immune reaction, through the production of the inhibitory cytokines IL-10 and transforming growth factor-(TGF)-β [27,28,29]. Th17 cells modulate Treg cell activities and increase host resistance to virus and bacteria, playing a positive role in the preservation of mucosal barrier integrity and, at later time points, in promoting recovery of normal architecture and lung function [30]. Indeed, IL-17 and IL-22, cytokines secreted by Th17 cells, are not only critical for host defense at mucosal surfaces, but also for tissue repair. An in-depth analysis of the complex interactions that occur in viral infections between Treg and Th17 cells is beyond the scope of this review. Infected airway epithelial cells may also promote a Th2 polarization, with recruitment-activation of mast cells, eosinophils and basophils, cells that have no identified role in clearing viral infection [20, 21, 25]. On airway epithelial cells, Th2 cytokines increase expression of adhesion molecules for HRVs, the predominant viruses producing recurrent wheezing and asthma exacerbation in children [31]. These include intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1, which acts as receptor for both type A and B HRVs, and cadherin-related family member 3 (CDHR3), which mediates type C HRVs binding and replication [19,20,21,22, 31,32,33]. In conclusion, independently from allergen exposure, some viruses, particularly type A and C HRV, may induce severe damage to the airways and a type 2 immune responses. The acquired Th2 phenotype polarization can subsequently become permanently skewed, if sustained by recurrent infections, and favored by environmental factors and by changes in microbiota composition [19, 27, 34, 35].

Physiological immaturity of the immune response

The increased susceptibility of infants and young children to respiratory infections is the result of the physiological immaturity of components of the systemic and local immune responses and, possibly, of sub-optimal complex inter-talk between microbiota and immune system effectors [4, 13, 14]. Immunotherapies that can modulate the immune response acting on immune cells and pathways as well as on gut microbiota are therefore desirable in childhood [36]. Both innate and adaptive arms of the immune system go through extended periods of post-natal maturation (Fig. 1). Neutrophils from neonates exhibit defective bactericidal activity [36,37,38,39]. NK cell proportions are not reduced in cord blood, but their IFN-γ production and cytotoxic activity are weaker [25, 26, 40]. The lower DC efficiency contributes to sustain the early “at birth” Th2 bias, related to elevated intrauterine IL-4 and IL-10 production [36]. The TH1/Th2 imbalance tends to persist over the first years of life, increasing the susceptibility to severe viral infections [36,37,38,39]. Reduced mobilization of DC precursors from bone marrow has also been described in neonates, associated with weak activation of the type I IFN pathways, low secretion of cytokines and decreased ability to present antigens to T-cells. These deficiencies are, at least in part, related to the reduced expression of surface proteins, involved in antigen presentation: the major histocompatibility complex II (MHC II) molecules and the CD40 and CD86 co-stimulatory molecules [27, 35, 39, 41, 42]. Naïve T-cells have non-specific receptors, responding to a wide range of peptides, as opposed to the highly-specific-antigen receptors of mature T-cells [27, 35, 39, 41, 42]. This explains the defective production of antigen-specific neutralizing antibodies by B-lymphocytes in response to infections [43]. Also, antigen-presenting B-lymphocytes lack MHC II and co-stimulatory CD40 and CD86 signals, leading to inefficient interactions with T-cells and antibody isotype switch [44]. The low titers of protective antibody, characterizing infancy, persist reaching adult levels only around adolescence [44, 45]. In young children Treg cells are inefficient as well, since they lack functional signals needed to promote viral clearance and prevent allergic sensitization [46]. Treg cells have been shown to play a critical role in preventing disease in RSV-infected mice, inhibiting lung inflammation and immune-mediated pathology by modulating CD8 T-cell response [47]. In RSV-infected infants, a reduction in abundance of activated Treg cells has been reported that persisted as the infection progressed and was associated with elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines in the nasal aspirates, increased neutrophilic inflammation, and exaggerated mucus production [48]. Allergen-specific Treg cells are also involved in prevention of atopic sensitization, through induction of a state of immune tolerance to inhaled allergens [49]. A key role in the maturation and modulation of the immune system is also thought to be played by the gut microbiota, where low diversity and/or dysbiosis in this phase of life can affect respiratory health [13, 14, 50].

Negative effects of immaturity of the immune cells in young children less than 3 years old. Both the innate and the adaptive arms of the immune system go through extended periods of post-natal maturation that persist over the first years of life, increasing the susceptibility to recurrent and severe viral respiratory infections

Gut microbiota

Early-life gut microbiota development has proven to be a critical factor in protecting against infections [50,51,52]. Recent evidence shows that gut commensal non-pathogenic species may influence immune response in other organs, notably airways [50,51,52]. This may be achieved through competitive colonization, direct effects of microbiota metabolic products on somatic functions, or through the activation of protective immune mechanisms. The gut microbiota develops immediately after birth, increases dramatically in diversity in the first three years of life and stabilizes thereafter to the adult pattern [51, 52]. Therefore, infancy represents a critical period in which the gut microbiota can be positively or negatively modified, with obvious implications for health outcomes. It has been hypothesized that inadequate maturation of the gut microbiome in early childhood, causing immune dysregulations, could potentially promote asthma in predisposed children [53, 54]. Amongst the variety of events that can negatively affect microbiota, a primary role is played by exposure to antibiotics [55,56,57,58]. Antibiotic use is associated with decreased total bacterial density, increased detection of gram-negative pathogenic bacilli and reduction in genera associated with fewer respiratory illnesses [55]. In addition to having a detrimental impact on the microbiota, inappropriate prescription of antibiotic treatments for viral infections can increase drug resistance among pathogenic bacteria [58]. Administration of bacterial extracts was shown to reduce antibiotic use by lowering risk of infection [14]. Furthermore, because of their nature, when given orally, they might also play a direct beneficial role on the gut microbiota thus also promoting respiratory health during the first years of life.

Oral bacterial lysates

Several bacterial lysates available for clinical use have shown to provide clinical benefit in patients with recurrent RTIs [14]. We will report and discuss only results of pre-clinical and clinical studies related to the “orally-delivered” bacterial lysates, whose mechanisms of action involve stimulation of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue and potentially promoting cross-talks between gut microbiota and immune system effectors. We will not include in this review Pidotimod, an orally delivered synthetic thymic dipeptide, and Polyvalent Mechanical Bacterial Lysate that is delivered by sublingual route [14]. The three key features of OBL supporting their use in prevention of viral infections and wheezing–asthma exacerbations are: (a) activation of a broad non-specific anti-infectious innate immune response; (b) prevention of excessive inflammatory response; (c) promotion of an adaptive Th1 type immune response with inhibition of an inefficient Th2-type polarization [14]. OBL are mechanical or chemical extracts of different strains of inactivated pathogenic respiratory bacteria species involved in the etiology of RTI. They contain conserved bacterial “pathogen-associated molecular patterns” (PAMPs), recognized by cellular “pattern recognition receptors” (PRRs), expressed by cells of the innate and adaptive immune responses [14, 59, 60]. Extracts that contain lysates from multiple bacterial strains, derived from different bacterial species, use bacterial diversity, as well as commonality preserved across the evolution of microorganisms, to act as PRR ligands. These active components expose the immune system to triggers like those that are carried by live infectious and commensal microorganisms, mimicking the natural exposure occurring in life, with consequent generation of a polyvalent immunomodulation [14, 60]. PRR-mediated pathogen recognition activates transcriptional pathways that promote the production of molecules required for a rapid and efficient immune response. After oral administration of OBL, bacterial antigens are sampled by microfold (M) cells and then by DCs resident in the Peyer’s patches of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (Fig. 2) [14, 60, 61]. The immune cascade generated by the activated DCs initiates homing of gut immune cells to the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in the airways.

After oral administration of bacterial lysates (OBL), bacterial antigens are taken up by microfold (M) cells and then processed by dendritic cells (DC) in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. DC stimulate the local immune response in the Peyer’s patches with subsequent migration of immune effector cells to the bronchial-associated lymphoid tissue of the lungs. From ref. #[61], modified with permission

Mechanisms of action of OBL: the experimental studies

Three OBL, administered by oral route, have shown to be effective in the prevention of viral infections in children: LW50020, RU 41740 and OM-85. The product that has been more extensively evaluated in recent, good quality studies is OM-85 [14, 60]. Studies performed in vitro, in experimental animals and in animal models relevant to human diseases, demonstrate that OBL can modulate the activity of a variety of cells, including DCs, monocyte-macrophages, B-cells, Treg cells and airway epithelial cells (Fig. 3) [14, 60, 61]. Only the most relevant features that may support the clinical use of these products in the prevention of viral RTIs and wheezing–asthma inception and recurrence in childhood will be described in detail.

OBL and modulation of DC functions

DCs are major players in both innate and adaptive responses against viruses. Studies performed in vitro and ex vivo in experimental animals demonstrate that OBL can induce DC maturation, increasing the production of anti-viral cytokines/chemokines and the expression of surface molecules involved in antigen presentation [14, 60]. In murine bone-marrow-derived DCs (BMDC) and human peripheral blood-derived DC (PBDC) cultures, through interaction with toll-like receptors and activation of NF-kB and MAPK dependent pathways, OBL can trigger the production of type I IFN-β, IL-8, CCL2, CCL20 and IFN-α, molecules involved in early immune reaction against viral infections [61, 62]. OBL-induced stimulation of murine peripheral blood derived DCs (PBDCs) increases the release of IL-12, a potent inducer of Th1 type lymphocytes, and down-regulated the “anti-inflammatory” cytokine IL-10 production [63]. To achieve optimum activation of T-cells, DCs must provide two specific signals: the first through binding of MHC II molecules, expressed on DC surface, to the T-cell receptors, and the second, through binding of DC co-stimulatory molecules CD40 and CD80/CD86 to CD40 ligand and CD28 receptors on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [34, 64]. Exposure to OBL of mice PBDCs and spleen derived DCs led to a significant increase in MHC II, CD40 and CD86 expression [63, 65]. Interestingly, a parallel reduction was detected of inducible T-cell co-stimulator ligand (ICOSL) expression, a molecule that enhances IgE antibody class switching and Th2 cytokine release [65]. Consistently, in splenocyte cultures from mice sensitized to ovalbumin (OVA), OBL increased production of anti-viral cytokine IFN-γ but decreased IgE and IL-4 release [66]. Moreover, in an infant rat model of OVA-induced sensitization, an increased ability to develop a Th1-dependent delayed response to OVA was detected, characterized by upregulation of IgG2 and IFN-γ release and an opposite effect on IL-4 release [67]. Thus, OBL may reinforce the postnatal maturation of Th1 function, a process thought to be physiologically driven also in humans by the gastrointestinal commensal microflora [50, 51].

OBL and modulation of mononuclear cell, macrophage, B- and Treg cell functions

In human and murine blood monocyte cultures and in murine bone marrow-derived macrophage cultures, OBL increased cytokine (IL-1, IL-2, IL-13 and TNF-α) release, adhesion molecule (LFA-1, MAC-1 and ICAM-1) expression, oxygen radicals (superoxide, nitric oxide, and nitrogen dioxide) production and killing of TNF-sensitive targets [66, 68,69,70,71]. Moreover, alveolar macrophages (AM) isolated from OBL-treated rats secreted significantly more nitric oxide and TNF-α upon in vitro stimulation with lipopolysaccharide [72]. These effects were due to a priming effect of OBL on the cells, because in vitro incubation of AM with OBL or intra-tracheal instillation of OBL did not result in altered cell activity [72]. OBL can induce an antigen-specific but also a polyclonal B-cell activation. In mice, treatment with OBL increased the levels of bacterial extract-specific IgA in Peyer’s patches and mesenteric lymph nodes [66], but also induced a polyclonal production of IgA and IgG in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) [65]. OBL also enhance the expression of the major MHC II and the co-stimulatory CD40 and CD86 molecules on B-cell surface [65]. Remarkably, OBL induced polyclonal activation of memory B-cells with production of influenza virus- and RSV-specific IgA and IgG in serum and BAL of animals not previously exposed to these viruses. These virus-specific IgA and IgG were functionally active, and significantly inhibited viral replication in vitro [65]. T- and B-lymphocyte migration from the gut to the lung, and antigen-specific immunoglobulin production in the respiratory tract were also detected in mice after oral administration of OBL [73]. In viral infections, Treg cells play a critical role in regulating effector T-lymphocytes, NK cells, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages. In atopic disorders, Treg cells promote allergen tolerance, decreasing Th2 inflammatory reactions [74,75,76,77]. In splenocyte cultures from OVA-induced asthmatic mice, the OBL OM-85 induced a significant increase in Treg cell frequency. In splenocyte supernatants opposite effects were detected in cytokine concentrations: IL-4 levels were decreased whilst the levels of IL-10 and TGF-β1, molecules involved in the modulation of allergic reactions and of anti-viral inflammatory responses, were increased [78].

OBL and human airway epithelial cell activation

In addition to providing a physical and functional barrier, bronchial epithelial cells (BEC) are actively involved in the initiation of host reactions to viral infection, through the expression of various receptors and effector proteins on their surface and the release of anti-inflammatory agents [79, 80]. Exposure to RU 41740 of human BEC line cultures, led to enhanced production of granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and of IL-8, cytokines involved in antiviral responses [81]. In primary human BEC cultures from healthy individuals and asthmatic patients, OM-85 upregulated the expression of the virus-counteracting proteins C1q-R and β-defensin [80]. Moreover, OM-85 significantly reduced HRV-induced virus replication as with it BEC death, at least partially reduced ICAM-1 expression, the main adhesion site for HRV type A and B and stimulated β-defensin release [80]. It therefore appears that OM-85 enhances BECs capacity to directly counter viral infections, by engagement of a variety of immuno-effector cells. The possibility that this effect could be translated in vivo, mediated by the gut-lung axis, is an attractive hypothesis.

Animal models relevant to human diseases

The possible “anti-viral” activities of OBL, shown by the in vitro studies, were confirmed in a mouse model of influenza virus infection (Fig. 4a). In animals treated for 10 days and then infected with sub-lethal doses of the virus, OM-85 decreased viral load in lung tissue [65]. Analysis of airway cellular infiltrates showed a reduction of neutrophilic inflammation with an increase in CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell proportions in OM-85 treated mice [65]. In the same experimental model, on day 7 following influenza infection, mice were exposed to a sublethal dose of either Klebsiella pneumoniae or Streptococcus pneumoniae [65]. Pre-treatment with OM-85 protected mice from bacteremia and significantly reduced all morbidity signs, suggesting that the anti-influenza-specific activation of the immune responses was also associated with an enhancement of specific anti-bacterial response against pathogens, whose PAMPs are included in OBL [82]. In addition to the effect on infection, a possible beneficial effect on allergen tolerance promoted by OBL-activated Treg cells was demonstrated in an asthmatic mouse model established with OVA challenge [78]. As compared to controls, in OBL pre-treated animals, a significant decrease of serum OVA-specific IgE concentration, BAL inflammatory cells (including eosinophils) percentages and BAL IL-4, IL-5 and TGF-β1 levels was noted [78]. In contrast, a significant increase in BAL levels of IFN-γ and IL-10 was detected [78]. Their lungs showed attenuation of mucous metaplasia and eosinophilic infiltration and enhanced presence of Treg cells [78]. In a similar OVA-induced asthmatic mouse model, in addition to reducing lung inflammatory cell infiltration, an OBL (OM-85) enhanced the anti-inflammatory activity of an inhaled corticosteroid [83]. In a different asthmatic mouse model (animals sensitized with Leishmania major LACK antigen), oral treatment with OM-85 suppressed airway inflammation through IL-10- and MyD88-dependent mechanisms and induced the activation of Treg cells [85]. Furthermore, CD4+ T-cells purified from the trachea of OM-85-treated mice conferred protection against airway inflammation when adoptively transferred into sensitized mice [85]. In summary, an interesting feature of OBL that emerges from the experimental studies and contributes to understanding their efficacy and at the same time their good safety profile, is their ability to act as “immunoregulators”, rather than only as “immunostimulators”. The immunoregulatory functions of these compounds include downregulation of expression of surface molecules associated with allergic Th2 type responses on DCs [65] and of HRV infectivity on BECs [80, 81] as well as promotion of Treg cells expansion [78, 83, 84].

Mouse models relevant to human diseases. a Sublethal influenza virus infection: pretreatment with OM-85 protected mice against viral infection but also from bacterial superinfections suggesting that the anti-influenza-specific activation of the immune system was associated with an enhancement of specific anti-bacterial responses. b Ova-induced allergic asthma: the expansion of Treg cells induced by OM-85 was associated with a significant decrease of the Th2 inflammatory response to the allergen and enhanced the response to inhaled corticosteroids

Clinical studies

Several reviews and meta-analyses have shown that OBL can be effective in prevention of recurrent RTI of the upper and lower airways in pediatric populations [14, 85,86,87,88,89]. Reduction of incidence, severity and duration of infections, as well as of antibiotic and drug use have been reported in randomized clinical trials on preschool and school-aged children and in adolescents treated with LW50020, RU 41740 and OM-85 [90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97]. Treatments were shown to be unaffected by co-administration of antibiotics and well tolerated, with a safety profile stable in nature and frequency over long-term use [90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97]. In addition, the efficacy of OM-85 treatment was shown to be unaffected by co-administration of influenza vaccination. A study on children aged 36–59 months with recurrent RTI showed that this OBL had no effects on the immunogenicity, safety and tolerability of inactivated influenza vaccine, and conferred additional benefit in terms of absenteeism and prevalence of infections [93]. In another study the same OBL has been shown to be effective in significantly reducing infectious wheezing episodes by 38% and their duration (2 days), in preschool children [94]. In a similar study, through the 12-month study period, RU 41740 significantly reduced the mean incidence of wheezing attacks by 37.9% and the mean incidence of acute RTIs by 31.4% [91]. In asthmatic children on long-term control medications (inhaled corticosteroids), OM-85 treatment was associated with a reduction of RTI frequency, significant at the 6 and 12-month control visits. The study also showed a significant increase of serum levels of IgA, IgG and human β defensin-1, a molecule that promotes DC and T-cell recruitment [95]. When given to school-aged asthmatic children and adolescents on conventional asthma therapy over a period of 12-month, OM-85 treatment reduced the frequency of RTI, asthma attacks, and antibiotic use [96]. These clinical effects were associated with an increase in the proportion of blood NK cells and IL-10 and IFN-γ serum levels, with a rise in the IFN-γ/IL-4 ratio [96]. The latter two studies suggest that OBL prophylaxis, when combined with conventional asthma treatment, can prevent recurrent RTI and wheezing/asthma attacks, putatively by modulating the immune response against viral infections. According to a recent meta-analysis and other combined study analyses, the greatest clinical benefit of OBL in wheezing and asthma should be expected in young children, in whom a history of frequent RTIs is more common, suggesting that infants could be an ideal population to test [60, 86,87,88,89, 96]. Nevertheless, based on the mode of action and the preliminary evidence on OBL in wheezing illness and asthma, some researchers have started testing OBL even in primary prevention in at risk infants/children. In a recent randomized clinical trial, at-risk infants (positive parental history of asthma and allergies) were treated with OM-85 during their first two winter-viral-seasons, and followed for a 3rd year, off treatment [98]. The frequency of severe lower RTI was significant lower in the 1st winter of the child’s life in those receiving OM-85. Moreover, the time to the 1st sLRTI was significantly longer, and the cumulative frequency of sLRTIs and the number of days with sLRTI symptoms were significantly lower for infants in the active group, suggesting a reduction in the overall inflammatory burden in the lower airways during this crucial period of early lung growth [98]. Finally, the ORBEX study, a large, multicenter, National Institute of Health-funded, randomized controlled trial, is currently ongoing in the USA. The study encompasses young (6–18-month-old) children at high asthma risk, i.e. having atopic dermatitis and/or parents or first-degree siblings with asthma [99]. The primary objective of this study is to evaluate whether an OBL, given for 10 days monthly for two consecutive years, can increase the time to occurrence of the first episode of wheezing lower respiratory tract illness during a third observation year, off therapy. The preliminary results of this trial are expected by December 2023.

Conclusions

OBLs appear to act on both the innate and the adaptive arms of the immune response, conferring efficacious broad immunoglobulin-related and cell-mediated immunity to the respiratory system. Additionally, experiments performed on BECs show that OBLs can also directly reduce viral infections, regardless of the engagement of the inflammatory and immuno-effector cells. Mechanistic data on the mode of action and results of clinical studies in pediatric patients can sustain the rationale for use of OBLs in the prophylaxis of viral RTIs and associated wheezing/asthma exacerbations. In addition to improving the quality of life of young patients and their families and to limiting the economic and social impact of these frequent respiratory disorders, the reduction of the frequency and severity of RTI is expected to decrease inappropriate use of antibiotics. Reduced prescription of antimicrobial drugs will have positive effects on the preservation of the physiologic gut microbiota composition and diversity, and importantly on reducing development of drug resistance. Ongoing (e.g. ORBEX) and future studies will show whether early OBL treatment can also be effective in prevention of long-term respiratory consequences of early and severe or recurrent RTI in childhood and will contribute to clarify the effect of OBLs both on immune system effectors and on microbiota and its metabolites.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AM:

-

Alveolar macrophages

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- BEC:

-

Bronchial epithelial cells

- BMDC:

-

Bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells

- CDHR3:

-

Cadherin-related family member 3

- CCL2:

-

Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 2

- CCL20:

-

Chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 20

- DC:

-

Dendritic cells

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HRV:

-

Human rhinovirus

- ICAM-1:

-

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- ICOSL:

-

Inducible T-cell co-stimulator ligand

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon gamma

- LFA-1:

-

Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1

- MAPK:

-

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- M cells:

-

Microfold cells

- MAC-1:

-

Macrophage antigen-1

- MHC II:

-

Major histocompatibility complex class II molecules

- NK cells:

-

Natural killer cells

- OBL:

-

Oral bacterial lysates

- OVA:

-

Ovalbumin

- PAMPs:

-

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PBDC:

-

Human peripheral blood-derived DC

- PRRs:

-

Pattern recognition receptors

- RTI:

-

Respiratory tract infections

- RSV:

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

- TGF-β:

-

Transforming growth factor-β

- Th17 cells:

-

Interleukin IL-17-producing T helper cells

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- Treg cells:

-

Regulatory T-cells

- NF-kB:

-

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

References

Griffin MR, Walker FJ, Iwane MK, Weinberg GA, Staat MA, Erdman DD. Epidemiology of respiratory infections in young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:188–92.

Nair H, Simoes EA, Rudan I, Dherani M, Madhi SA, Singleton RJ, et al. Global and regional burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1380–90.

Brealey JC, Sly PD, Young PR, Chappell KJ. Viral bacterial co-infection of the respiratory tract during early childhood. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/femsle/fnv062.

Tregoning JS, Schwarze J. Respiratory viral infections in infants: causes, clinical symptoms, virology, and immunology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:74–98.

Murphy T, Bakaletz L, Smeesters P. Microbial interactions in the respiratory tract. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(Suppl 10):S121–6.

Cohen R, Just J, Koskas M, Bingen E, Boucherat M, Bourrillon A, François P, et al. Recurrent respiratory tract infections: how should we investigate and treat. Arch Pediatr. 2005;12:183–90.

de Martino M, Ballotti S. The child with recurrent respiratory infections: normal or not? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18(Suppl. 18):13–8.

Townsi N, Laing IA, Hall GL, Simpson SJ. The impact of respiratory viruses on lung health after preterm birth. Eur Clin Respir J. 2018;5:1487214.

Martinez FD. The origins of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in early life. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:272–7.

Brand PL, Caudri D, Eber E, Gaillard EA, Garcia-Marcos L, Hedlin G, et al. Classification and pharmacological treatment of preschool wheezing: changes since 2008. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1172–7.

Ruszczyński M, Ambrożej D, Adamiec A, Ruszczynski M, Elenius V, Cavkaytar O, et al. Management of preschool wheezing and asthma in children: systematic review of guidelines and quality appraisal with the Agree II Instrument. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31:206–9.

Guilbert TW, Morgan WJ, Zeiger RS, Mauger DT, Boehmer SJ, Szefler SJ, et al. Long-term inhaled corticosteroids in preschool children at high risk for asthma. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1985–97.

Fuchs O, Genuneit J, Latzin P, Büchele G, Horak E, Loss G, Sozanska B, et al. Farming environments and childhood atopy, wheeze, lung function, and exhaled nitric oxide. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(382–8):e6.

Esposito S, Soto-Martinez ME, Feleszko W, Jones MH, Shen KL, Schaad UB. Nonspecific immunomodulators for recurrent respiratory tract infections, wheezing and asthma in children: a systematic review of mechanistic and clinical evidence. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;18:198–209.

Le Souëf P. Viral infections in wheezing disorders. Eur Respir Rev. 2018;27:170133.

Man WH, de Steenhuijsen Piters WA, Bogaert D. The microbiota of the respiratory tract: gatekeeper to respiratory health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:259–70.

Jackson DJ, Hartert TV, Martinez FD, Weiss ST, Fahy JV. Asthma, NHLBI Workshop on the primary prevention of chronic lung diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(Suppl 3):139–45.

Jartti T, Gern JE. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:895–906.

Jartti T, Smits HH, Bønnelykke K, Bircan O, Elenius V, Konradsen JR, et al. EAACI Task Force on Clinical Practice Recommendations on Preschool Wheeze. Bronchiolitis needs a revisit: distinguishing between virus entities and their treatments. Allergy. 2019;74:40–52.

Rossi GA, Colin AA. Infantile respiratory syncytial virus and human rhinovirus infections: respective role in inception and persistence of wheezing. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:774–89.

Makris S, Johnston S. Recent advances in understanding rhinovirus immunity. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1537.

Coverstone AM, Wang L, Sumino K. Beyond respiratory syncytial virus and rhinovirus in the pathogenesis and exacerbation of asthma: the role of metapneumovirus, bocavirus and influenza virus. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2019;39:391–401.

Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, Zhang J, Li YY, Qu J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 18]. N Engl J Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2005073.

Yeganeh B, Xia C, Movassagh H, Koziol-White C, Chang Y, Al-Alwan L, et al. Emerging mediators of airway smooth muscle dysfunction in asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26:105–11.

Rossi GA, Colin AA. Respiratory syncytial virus-host interaction in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis and its impact on respiratory morbidity in later life. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:320–31.

Holt PG, Mok D, Panda D, Renn L, Fabozzi G, deKlerk NH, et al. Developmental regulation of type 1 and type 3 interferon production and risk for infant infections and asthma development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143:1176–82.

Chiu C, Openshaw PJ. Antiviral B cell and T cell immunity in the lungs. Nat Immunol. 2015;16:18–26.

Yoo JK, Kim TS, Hufford MM, Braciale TJ. Viral infection of the lung: host response and sequelae. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1263–76.

Wegrzyn AS, Jakiela B, Rückert B, Jutel M, Akdis M, Sanak M. T-cell regulation during viral and nonviral asthma exacerbations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:194–7.

Pociask DA, Scheller EV, Mandalapu S, McHugh KJ, Enelow RI, Fattman CL, et al. IL-22 is essential for lung epithelial repair following influenza infection. Am J Pathol. 2013;182:1286–96.

Bianco A, Sethi SK, Allen JT, Knight RA, Spiteri MA. Th2 cytokines exert a dominant influence on epithelial cell expression of the major group human rhinovirus receptor, ICAM-1. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:619–26.

Stenberg Hammar K, Niespodziana K, van Hage M, Kere J, Valenta R, Hedlin G, et al. Reduced CDHR3 expression in children wheezing with rhinovirus. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2018;29:200–6.

Bochkov YA, Gern JE. Rhinoviruses and their receptors: implications for allergic disease. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16:30.

Thomas AO, Lemanske RF Jr, Jackson DJ. Infections and their role in childhood asthma inception. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014;25:122–8.

Lan F, Zhang N, Gevaert E, Zhang L, Bachert C. Viruses and bacteria in Th2-biased allergic airway disease. Allergy. 2016;71:1381–92.

Sly PD, Holt PG. Role of innate immunity in the development of allergy and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11:127–31.

Renz H, Holt PG, Inouye MI, Logan AC, Prescott SL, Sly PD. An exposome perspective: early life events and immune development in a changing world. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:24–40.

Gahr M, Schulze M, Scheffczyk D, Speer CP, Peters JH. Diminished release of lactoferrin from polymorphonuclear leukocytes of human neonates. Acta Haematol. 1987;77:90–4.

Basha S, Surendran N, Pichichero M. Immune responses in neonates. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2014;10:1171–84.

Sundström Y, Nilsson C, Lilja G, Kärre K, Troye-Blomberg M, Berg L. The expression of human natural killer cell receptors in early life. Scand J Immunol. 2007;66:335–44.

Remot A, Descamps D, Jouneau L, Laubreton D, Dubuquoy C, Bouet S, et al. Flt3 ligand improves the innate response to respiratory syncytial virus and limits lung disease upon RSV reexposure in neonate mice. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46:874–84.

Holt PG, Upham JW, Sly PD. Contemporaneous maturation of immunologic and respiratory functions during early childhood: implications for development of asthma prevention strategies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:16–24.

Langrish CL, Buddle JC, Thrasher AJ, Goldblatt D. Neonatal dendritic cells are intrinsically biased against Th-1 immune responses. Clin Exp Immunol. 2002;128:118–23.

Tucci A, Mouzaki A, James H, Bonnefoy JY, Zubler RH. Are cord blood B cells functionally mature? Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84:389–94.

Diesner SC, Förster-Waldl E, Olivera A, Pollak A, Jensen-Jarolim E, Untersmayr E. Perspectives on immunomodulation early in life. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:210–23.

Bacchetta R, Gambineri E, Roncarolo MG. Role of regulatory T cells and FOXP3 in human diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:227–35.

Fulton RB, Meyerholz DK, Varga SM. Foxp3+ CD4 regulatory T cells limit pulmonary immunopathology by modulating the CD8 T cell response during respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol. 2010;185:2382–92.

Christiaansen AF, Syed MA, Ten Eyck PP, Hartwig SM, Durairaj L, Kamath SS, et al. Altered Treg and cytokine responses in RSV-infected infants. Pediatr Res. 2016;80:702–9.

Minnicozzi M, Sawyer RT, Fenton MJ. Innate immunity in allergic disease. Immunol Rev. 2011;242:106–27.

Martinez FD. Childhood asthma inception and progression: role of microbial exposures, susceptibility to viruses and early allergic sensitization. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2019;39:141–50.

Kunisawa J, Fukuyama S, Kiyono H. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues in the aerodigestive tract: their shared and divergent traits and their importance to the orchestration of the mucosal immune system. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:557–72.

Jackson DJ, Gern JE, Lemanske RF Jr. Lessons learned from birth cohort studies conducted in diverse environments. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:379–86.

Stokholm J, Blaser MJ, Thorsen J, Rasmussen MA, Waage J, Vinding RK, et al. Maturation of the gut microbiome and risk of asthma in childhood. Nat Commun. 2018;9:141.

Di Cicco M, Pistello M, Jacinto T, Ragazzo V, Piras M, Freer G, et al. Does lung microbiome play a causal or casual role in asthma? Pediatr Pulmonol. 2018;53:1340–5.

Fouhy F, Guinane CM, Hussey R, Ryan CA, Dempsey EM, et al. High-throughput sequencing reveals the incomplete, short-term recovery of infant gut microbiota following parenteral antibiotic treatment with ampicillin and gentamicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:5811–20.

Ni J, Friedman H, Boyd BC, McGurn A, Babinski P, Markossian T, et al. Early antibiotic exposure and development of asthma and allergic rhinitis in childhood. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:225.

Korpela K, Salonen A, Virta LJ, Kekkonen RA, Forslund K, Bork P, et al. Intestinal microbiome is related to lifetime antibiotic use in Finnish pre-school children. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10410.

Ventola CL. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharm Ther. 2015;40:277–83.

Pavot V, Rochereau N, Genin C, Verrier B, Paul S. New insights in mucosal vaccine development. Vaccine. 2012;30:142.

Kearney SC, Dziekiewicz M, Feleszko W. Immunoregulatory and immunostimulatory responses of bacterial lysates in respiratory infections and asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015;114:364–9.

Cerutti A, Rescigno M. The biology of intestinal immunoglobulin A responses. Immunity. 2008;28:740–50.

Parola C, Salogni L, Vaira X, Scutera S, Somma P, Salvi V, et al. Selective activation of human dendritic cells by OM-85 through a NF-kB and MAPK dependent pathway. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e82867.

Spisek R, Brazova J, Rozkova D, Zapletalova K, Sediva A, Bartunkova J. Maturation of dendritic cells by bacterial immunomodulators. Vaccine. 2004;22:2761–8.

Planelles L, Thomas MC, Marañón C, Morell M, López MC. Differential CD86 and CD40 co-stimulatory molecules and cytokine expression pattern induced by Trypanosoma cruzi in APCs from resistant or susceptible mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:41–7.

Pasquali C, Salami O, Taneja M, Gollwitzer ES, Trompette A, Pattaroni C, et al. Enhanced mucosal antibody production and protection against respiratory infections following an orally administered bacterial extract. Front Med. 2014;1:41.

Huber M, Mossmann H, Bessler WG. Th1-orientated immunological properties of the bacterial extract OM-85-BV. Eur J Med Res. 2005;10:209–17.

Bowman LM, Holt PG. Selective enhancement of systemic Th1 immunity in immunologically immature rats with an orally administered bacterial extract. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3719–27.

Sozzani S, D’Alessandro F, Capsoni F, Luini W, Barcellini W, Guidi G, et al. In vitro modulation of human monocytes functions by RU 41740. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1988;10:93–102.

Baladi S, Kantengwa S, Donati YR, Polla BS. Effects of the bacterial extract OM-85 on phagocyte functions and the stress response. Mediators Inflamm. 1994;3:143–8.

Mauël J. Stimulation of immunoprotective mechanisms by OM-85 BV. A review of results from in vivo and in vitro studies. Respiration. 1994;61(Suppl 1):8–15.

Marchant A, Goldman M. OM-85 BV upregulates the expression of adhesion molecules on phagocytes through a CD 14-independent pathway. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1996;18:259–62.

Broug-Holub E, Persoons JH, Schornagel K, Kraal G. Changes in cytokine and nitric oxide secretion by rat alveolar macrophages after oral administration of bacterial extracts. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101:302–7.

Ruedl C, Albini B, Böck G, Wick G, Wolf H. Oral administration of a bacterial immunomodulator enhances murine intestinal lamina propria and Peyer’s patch lymphocyte traffic to the lung: possible implications for infectious disease prophylaxis and therapy. Int Immunol. 1993;5:29–36.

Rouse BT, Sarangi PP, Suvas S. Regulatory T cells in virus infections. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:272–86.

Hawrylowicz Catherine M. Regulatory T cells and IL-10 in allergic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1459–63.

Strickland DH, Judd S, Thomas JA, Larcombe AN, Sly PD, Holt PG. Boosting airway T-regulatory cells by gastrointestinal stimulation as a strategy for asthma control. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:43–52.

Jiang J, Wang Y, Tang X, Yao Y, Zhou J. Regulation of viral infection-induced airway remodeling cytokine production by the TLR3-EGFR signaling pathway in human bronchial epithelial cells. COPD. 2016;13:750–5.

Fu R, Li J, Zhong H, Zeng X, Deng M, Sun Y, et al. Broncho-Vaxom attenuates allergic airway inflammation by restoring GSK3b-related T regulatory cell insufficiency. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e92912.

Gao W, Li L, Wang Y, Zhang S, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ, et al. Bronchial epithelial cells: the key effector cells in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Respirology. 2015;20:722–9.

Roth M, Pasquali C, Stolz D, Tamm M. Broncho Vaxom (OM-85) modulates rhinovirus docking proteins on human airway epithelial cells via Erk1/2 mitogen activated protein kinase and cAMP. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188010.

Aloui R, Gormand F, Guibert B, Corallo F, Perrin Fayolle M, et al. RU 41740 (Biostim) stimulates the production of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-8 by human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:1351–3.

Rossi GA, Bessler W, Ballarini S, Pasquali C. Evidence that a primary anti-viral stimulation of the immune response by OM-85 reduces susceptibility to a secondary respiratory bacterial infection in mice. Ital J Pediatr. 2018;44:112.

Liu C, Huang R, Yao R, Yang A. The immunotherapeutic role of bacterial lysates in a mouse model of asthma. Lung. 2017;195:563–9.

Navarro S, Cossalter G, Chiavaroli C, Kanda A, Fleury S, Lazzari A, et al. The oral administration of bacterial extracts prevents asthma via the recruitment of regulatory T cells to the airways. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:53–65.

Del-Rio-Navarro BE, Espinosa Rosales F, Flenady V, Sienra-Monge JJ. Immunostimulants for preventing respiratory tract infection in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD004974.

Steurer-Stey C, Lagler L, Straub DA, Steurer J, Bachmann LM. Oral purified bacterial extracts in acute respiratory tract infections in childhood: a systematic quantitative review. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:365–76.

Jurkiewicz D, Zielnik-Jurkiewicz B. Bacterial lysates in the prevention of respiratory tract infections. Otolaryngol Pol. 2018;72:1–8.

Yin J, Xu B, Zeng X, Shen K. Broncho-Vaxom in pediatric recurrent respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;54:198–209.

Rozy A, Chorostowska-Wynimko J. Bacterial immunostimulants-mechanism of action and clinical application in respiratory diseases. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2008;76:353–9.

Bonfils P. Prevention of infections of the respiratory tract in children with RU 41740. Presse Med. 1988;17:1450–2.

Paupe J, Paupe G. Biostim prevention of recurrent respiratory infections in children. A double-blind versus placebo study. Ann Pediatr. 1986;33:843–5.

Rutishauser M, Pitzke P, Grevers G, van Aubel A, Elsasser U, Kämmereit A. Use of a polyvalent bacterial lysate in patients with recurrent respiratory tract infections: results of a prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study. Adv Ther. 1998;15:330–41.

Esposito S, Marchisio P, Prada E, Daleno C, Porretti L, Carsetti R, et al. Impact of a mixed bacterial lysate (OM-85 BV) on the immunogenicity, safety and tolerability of inactivated influenza vaccine in children with recurrent respiratory tract infection. Vaccine. 2014;32:2546–52.

Razi CH, Harmancı K, Abacı A, Özdemir O, Hızlı S, Renda R, et al. The immunostimulant OM-85 BV prevents wheezing attacks in preschool children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:763–9.

Liao JY, Zhang T. Influence of OM-85 BV on hBD-1 and immunoglobulin in children with asthma and recurrent respiratory tract infection. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2014;16:508–12.

Lu Y, Li Y, Xu L, Xia M, Cao L. Bacterial lysate increases the percentage of natural killer T cells in peripheral blood and alleviates asthma in children. Pharmacology. 2015;95:139–44.

Han RF, Li HY, Wang JW, Cong XJ. Study on clinical effect and immunologic mechanism of infants capillary bronchitis secondary bronchial asthma treated with bacterial lysates Broncho-Vaxom. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:2151–5.

Sly PD, Galbraith S, Islam Z, Holt B, Troy N, Holt PG. Primary prevention of severe lower respiratory illnesses in at-risk infants using the immunomodulator OM-85. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:870–2.

ORal Bacterial EXtracts for the prevention of wheezing lower respiratory-tract illness (ORBEX) trial (NCT02148796).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors made substantial contributions to the conception of the manuscript; GAR drafted the initial manuscript, all the other authors substantively revised and edited the text and gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to the publication of the manuscript.

Competing interests

GAR received lecture and consultation fees from Polichem S.A., Pierre Fabre, Vifor Pharma, Chiesi, Valeas; PP received speakers and consultations honoraria from AstraZeneca, Novartis, GSK, 4Life Pharma, ALK, Mundipharma; WF received speaker’s honoraria from Vifor Pharma, Sandoz, Ranbaxy, GSK. SB is employee of OM Pharma, a Vifor Pharma Company. AAC received lecture and consultation fees from Vifor Pharma.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rossi, G.A., Pohunek, P., Feleszko, W. et al. Viral infections and wheezing–asthma inception in childhood: is there a role for immunomodulation by oral bacterial lysates?. Clin Transl Allergy 10, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-020-00322-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13601-020-00322-1