Abstract

The adverse effects of antibiotics have attracted widespread attention, thus reducing the use of antibiotics in animal feed has become a very important issue in improving of the health of livestock. The effects of Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium) on growth performance and gut microbiota in weaned piglets were investigated in the present study. Piglets were randomly assigned to four treatments: a control group fed with a diet containing 75 mg/kg aureomycin (Diet 1 group) and three experimental groups fed with diets of 50 mg/kg aureomycin (Diet 2 group), 50 mg/kg aureomycin + 9 × 105 CFU/g E. faecium (Diet 3 group), or 50 mg/kg aureomycin + 1.2 × 106 CFU/g E. faecium (Diet 4 group). Their gut microbial communities were analyzed by sequencing the V3–V4 region of the 16SrRNA gene. The results showed that the final body weights and the average daily gain of the weaned piglets in the Diet 2 group were higher (P = 0.05) than those in the Diet 1 or Diet 3 group. Decreasing trends (P = 0.08) was observed in mortality rate in the Diet 3 and 4 group when compared with that in the Diet 1 group. Increases in the Sobs, Chao1, ACE, and Shannon indexes and a decrease in the Simpson index were observed at intervals from day 1 to 14 (P < 0.05). The Sobs, Chao1, and ACE indexes in the Diet 3 group were the lowest on day 14 (P < 0.05). The abundance of Bacteroidetes was increased and that of Proteobacteria was decreased from day 1 to 7, but both of them kept stable from day 7 to 14. Besides, the lowest abundance of Fusobacteria, Lentisphaerae, and Planctomycetes was observed on day 1 and the lowest abundance of Actinobacteria was observed on day 14 in the Diet 3 group (P < 0.05). Overall, these results suggest that the antibiotics and E. faecium interventions result in different changes in the gut microbiota, and a reduced antibiotics diet supplemented with 1.2 × 106 CFU/g E. faecium does not affect the growth performance in weaned piglets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antibiotics have been widely used in the prevention of diarrhea and the improvement of the growth of livestock. However, the adverse effects of antibiotics, such as residues in meat products and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (van den Bogaard and Stobberingh 2000), have attracted widespread attention. Thus, antibiotics are forbidden to be used as additives in animal feed in some countries (Casewell et al. 2003). In recent years, the use of antibiotics in animal feed has been gradually reduced in China, but is still sometimes available in animal feed. Therefore, it’s of great significance to find alternatives to antibiotics in animal feed to promote the development of livestock industry.

Probiotic feed additives have been proposed as alternatives to antibiotics due to their positive effects on hosts (Liu et al. 2014; Abhisingha et al. 2017; Yu et al. 2017). Enterococcus faecium is widely used as a probiotic supplement in feed. Previous studies showed a beneficial effect of probiotic E. faecium on diarrhea, growth performance, and microbiota composition (Zeyner and Boldt 2006; Bednorz et al. 2013; Wang et al. 2016; Lan and Kim 2017), suggesting that antibiotics may be replaced by E. faecium. However, some studies indicate that E. faecium treatment has no effects on body weight gain (Busing and Zeyner 2015), feed intake, or feed efficiency in piglets (Taras et al. 2006). Thus, the effects of E. faecium on growth performance in piglets remain highly controversial. Thus, further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms in the effect of E. faecium.

In recent years, the roles of gut microbiota have been extensively investigated and revealed (Kahrstrom et al. 2016; Sonnenburg and Backhed 2016). Symptoms of metabolic syndrome of the hosts such as obesity are closely associated with dysbiosis of the gut microbiota (Sen et al. 2017). The gut microbiota have a major impact on the health of piglets; for instance, the production of amino acids, the fermentation of carbohydrates, the maintenance integrity of the intestinal villi, and the protection from pathogenic bacteria (Gresse et al. 2017). The decrease in the population of Lactobacillus genus and the increase in the population of Enterococcus and Escherichia coli were observed in early weaning piglets (Wei et al. 2017). Moreover, changes in the microbial community structure are seen in piglets with intestinal disorders, such as diarrhea (Li et al. 2014). Obviously, gut microbiota are an important factor that affects the growth of piglets. The composition of the microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract varies between piglets fed with an antibiotics-supplemented diet and those fed with an antibiotics-free diet (Mu et al. 2017), which indicates that antibiotics-induced changes in the gut microbiota may lead to the changes in the growth of piglets (Andreas et al. 2016).

Although some studies have focused on the roles of antibiotics and E. faecium in the growth of piglets (Wang et al. 2013, 2016; Lan and Kim 2017), there’s still little information about the effects of a diet with reduced antibiotics and E. faecium supplementation on the growth and fecal bacterial community structure of animals. Early weaned piglets are exposed to several stress factors which make gut microbiota dramatically change and make the diarrhea increase without antibiotics treatment (Vondruskova et al. 2010; Li et al. 2017). Therefore, this study is conducted to evaluate the effects of antibiotics and E. faecium on growth performance and gut microbiota in weaned piglets.

Materials and methods

Animals and experimental treatments

The experimental design and procedure presented in this study are reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the South China Agricultural University.

364 weaned piglets (Duroc × Landrace × Large White) with an initial body weight of 7.03 ± 0.03 kg were randomly assigned to four treatments with seven pens, and each pen contains 13 weaned piglets. The piglets are fed with water and a corn and soybean meal-based diet (Table 1) ad libitum through a nipple drinker and a feeder. The piglets in the control group were fed with a basal diet containing 75 mg/kg aureomycin (Diet 1 group), and those in the three experimental groups were fed a basal diet with the following supplements: 50 mg/kg aureomycin (Diet 2 group), 50 mg/kg aureomycin + 9 × 105 CFU/g E. faecium (Diet 3 group), or 50 mg/kg aureomycin + 1.2 × 106 CFU/g E. faecium (Diet 4 group). E. faecium (China Center for Type Culture Collection, Wuhan, China, CCTCC No. M2011031, 3 × 109 CFU/g) was provided by Huada-real Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). The experiment was performed for 14 days.

Sample collection and measurements

Initial body weight and final body weight of the piglets were measured at the age of 21 days (experimental day 1) and 35 days (experimental day 14) to calculate the average daily weight gain. The amounts of feed offered and refused were recorded every day to confirm the individual daily feed intake, and the feed efficiency was calculated by the weight gain/feed intake ratio based on the data of feed intake and body weight. The diarrhea rate was calculated according to the following formula (Hu et al. 2017): A/(B × C), where A is the number of piglets with diarrhea in the pen, B is the total number of piglets in the pen, and C is the number of experimental days.

DNA extraction and 16SrRNA gene sequencing

72 fecal samples were collected after feeding, with 18 samples collected per group, and 6 samples collected per period (on day 1, 7, and 14, respectively). Total genomic DNA were extracted from fecal samples using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the instructions. A NanoDrop ND-1000 system (Thermo Fisher, Wilmington, DE, USA) was used to measure the concentration of DNA. The V4 region of the 16SrRNA gene was amplified using primers 515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) (Zeng et al. 2017). Total reaction volume of 20 μL comprised 2 μL 2.5 mM dNTPs, 4 μL 5×FastPfu buffer (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), 0.4 μL FastPfu Polymerase, 0.8 μL of each primer, 1 μL DNA template, and 11 μL ddH2O. The PCR program included a 3-min incubation at 95 °C, followed by 27 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, and annealing and extension at 55 °C for 30 s and at 72 °C for 45 s. All samples examined in this study provided complete DNA samples, as agarose gels clearly showed the amplified products. After PCR amplification, amplicons were extracted from 1.2 agarose gels and purified using SanPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Sangon Biotech, China). Purified amplicons were operated using paired-end sequencing by Illumina MiSeq. The instructions of the platform and the manufacturer were from a commercial service provider (BGI, Shenzhen, China). Sequences with an average phred score lower than 30, ambiguous bases, homopolymer runs exceeding 6 bp, primer mismatches, or sequence lengths shorter than 100 bp were removed. All the procedures except DNA extraction were conducted by the BGI Company.

Bioinformatics analysis

The bioinformatics analysis will be carried out based on the sequencing data. The raw data were analyzed by QIIME (http://qiime.org/) (Caporaso et al. 2010) and FLASH (v1.2.11) (Magoc and Salzberg 2011), and were filtered to eliminate adapters and low-quality reads to obtain clean reads, and then overlapped paired-end reads were merged to create tags. The tags were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with sequence similarity of 97% using USEARCH (v7.0.1090) (Edgar 2013). Representative OTU sequences were taxonomically classified by Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Classifier trained on Greengene (V201305) reference database (DeSantis et al. 2006). Finally, alpha diversity was analyzed based on OTUs. Principal component analysis (PCA) plots of the dissimilarity metrics were also visualized using the R (v3.0.3). All the raw sequences were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive with an Accession Number of SAMN10234820-SAMN10234874.

Statistical analysis

The growth performance, observed OTUs, and alpha diversity were statistically analyzed by repeated-measure one-way ANOVA using SPSS 17.0 (SPPS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Duncan’s multiple-range test and multivariate analysis of variance performed in the case of Mauchly’s test of Sphericity showed P > 0.05 and P < 0.05, respectively. The relative abundance at phylum and genus levels was statistically analyzed through non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests. The relationships between mortality diarrhea rate and diet were statistically analyzed through Chi squared test. Variations between different methods were considered statistically remarkable at P ≤ 0.05, with the trends toward significance indicated by 0.05 < P < 0.10.

Results

Growth performance

As shown in Table 2, compared with the Diet 1 and Diet 3 groups, the final body weight in the Diet 2 group increased (P = 0.05) by 4.13% and 3.51%, respectively, and the average daily gain in the Diet 2 group increased (P ˂ 0.05) by 14.26% and 11.82%, respectively. Descending trends (P = 0.08) were observed in mortality rate in Group 3 and 4 compared with that in Group 1.

Diversity of fecal bacterial communities

Quality control, and chimera removal, 5,769,672 high-quality sequences were obtained from all fecal samples after filtering (Table 3), with an average of 1,442,418 sequences per group and 80,134 per sample. In total, 1852 OTUs were generated. The fecal bacterial community on day 14 in Diet 3 group had fewer OTUs (P ˂ 0.05) than those in the other groups (Fig. 1C).

Comparison of the OTUs of the four groups on different experimental days. The number of observed OTUs in fecal samples collected at experimental day 1 (A), day 7 (B), and day 14 (C) sharing the sequence similarity of ≥ 97% is shown. a,bSmall letter superscript represents significant difference (P < 0.05). Data were statistically analyzed by repeated-measures one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple-range test

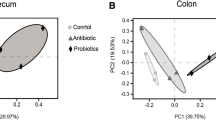

As indicated in Table 4, increases in the Sobs, Chao1, ACE, and Shannon index values and a decrease in the Simpson index value were observed at intervals from day 1 to 14. On day 14, the Sobs, Chao1, ACE, and Shannon index values in Diet 2 group were higher than those in the other groups (Fig. 2A–D). The Diet 3 group exhibited lower (P < 0.05) values of the Sobs, Chao1, and ACE indexes than the Diet 1 and Diet 2 groups (Fig. 2A–C). No difference of alpha diversity was found between Diet 1 and Diet 2 groups (P > 0.05). The PCA showed that the samples were clustered together on several experimental days (Fig. 3). The rarefaction curve of all samples has reached a stable value (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

Alpha diversity indices of fecal bacterial communities of weaned piglets on day 14 in different groups. A–E Observed species, chao 1, ace, simpson, and shannon, respectively. a,bSmall letter superscript represents significant difference (P < 0.05). Data were statistically analyzed by one-way ANOVA, followed by Duncan’s multiple-range test

Fecal bacterial community structure

At phylum level, the abundance of seven phyla was ≥ 0.5%: Bacteroidetes, Euryarchaeota, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Proteobacteria, Spirochaetes, and Synergistetes. Among them, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Spirochaetes, and Proteobacteria were the dominant phyla, accounting for more than 95% of the total fecal bacterial community (Fig. 4). The abundance of Bacteroidetes was increased whereas that of Proteobacteria was decreased from day 1 to 7 and remained stable from day 7 to 14 (Fig. 4). On day 1, the abundance of Bacteroidetes, Euryarchaeota, Spirochaetes, and Planctomycetes were higher in the Diet 1 group than in Diet 2 group (Fig. 4), and Diet 3 group exhibited higher (P < 0.05) abundances of Spirochaetes and Fibrobacteres than the other groups (Fig. 5a, b); on days 7 and 14, the abundance of Proteobacteria was higher in the Diet 3 group than in the other groups (Fig. 5c), and the abundance of Firmicutes was higher in the Diet 2 group than in the Diet 1 group (Fig. 4). Lower abundance of actinobacteria was observed (P < 0.05) in Diet 3 group when compared to Diet 4 group on day 14 (Fig. 5d).

Distribution of bacterial community structure at phylum level in different phases. The relative abundances lower than 0.01% are not shown. 1 day, 7 days, and 14 days represent experimental day 1, 7, and 14, respectively. The relative abundance at phylum level was statistically analyzed through non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests

Bacterial genera that rank the top 50 are shown in Fig. 6. A higher abundance of Actinobacillus, Bacteroides, Butyricimonas, Bilophila, Escherichia, Fusobacterium, Odoribacter, and Pyramidobacter and a lower abundance of Anaeroplasma, Anaerovibrio, Bulleidia, Butyricicoccus, Coprococcus, Fibrobacter, Lachnospira, Oribacterium, Roseburia, Succinivibrio, and YRC22 were found on day 1 than those on day 7 and 14. Diet 2 group exhibits the highest abundance of Lactobacillus and Treponema, and the lowest abundance of Prevotella (Fig. 6). On day 7, the highest (P < 0.05) abundance of Anaerovibrio and Phascolarctobacterium was observed in the Diet 4 group (Fig. 7a). On day 14, the abundance of 02d06 was decreased (P < 0.05) in the Diet 3 group (Fig. 7b), whereas that of Anaerovibrio (Fig. 7b) was increased (P < 0.05).

Genus-level taxonomic composition of the bacterial communities of feces in weaned pigs in different phases. The feces with the highest and lowest bacterial levels are shown in green and red respectively. Bacterial genera that rank the top 50 are listed. 1 day, 7 days, and 14 days represent experimental day 1, 7, and 14, respectively

The bacterial abundance of genera significantly differs in different phases. Only the data whose differences with P-values are lower than 0.05 are shown. 7 d (a) and 14 d (b) represent experimental day 7 and 14, respectively. The relative abundance at genus level was statistically analyzed through non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Discussion

Antibiotics used as growth promoters in feed may bring negative side effects (Chee-Sanford et al. 2001). Therefore, the development of alternatives to antibiotics and a reduction in the use of antibiotics in animal feed are urgently needed. The probiotic bacteria E. faecium provides various benefits of health to piglets (Bednorz et al. 2013; Klingspor et al. 2013; Siepert et al. 2014). In the present study, weaned piglets were selected as models to evaluate the effects of a diet with reduced levels of antibiotics and E. faecium supplementation for a 14-day intervention period. Significant increases in both final body weight and average daily gain were observed in the Diet 2 group, which indicates that growth performance in weaned piglets fed with a diet with reduced levels of antibiotics was promoted. This is a novel finding, demonstrating that diets with decreasing aureomycin levels ranging from 75 to 50 mg/kg alone had a positive effect on the growth of weaned piglet. However, previous studies showed that dietary supplementation with antibiotics had no effects on final body weight or average daily gain of piglets (Puiman et al. 2013; Yu et al. 2017). In addition, the results of the present study on the effects of dietary antibiotic supplementation are not consistent with those of Wang et al. (2013). Wang et al. claimed that dietary supplementation with 150 mg/kg aureomycin increased the final body weight and weight gain of piglets, and suggested that growth performance in weaned piglets is associated with the dosage of aureomycin used in feed. Interestingly, final body weight and average daily gain of weaned piglets did not change in the Diet 4 group, but were lower in the Diet 3 group than in the Diet 2 group; This does not agree with the findings of Mallo et al. (2010), who proposed that addition of E. faecium to the diet promoted the growth and the feed conversion of weaned piglets. Similar results were also found in the treatment of weaned piglets with E. faecium (Hu et al. 2015). The discrepancy between these previous studies and the present study could be explained by the differences in the dosages of E. faecium used in the diet. Here, the dosages of E. faecium in the Diet 3 and 4 groups were 9 × 105 CFU/g and 1.2 × 106 CFU/g, respectively, whereas those of Mallo et al. (2010) and Hu et al. (2015) were 106 CFU/g and 2.5 × 106 CFU/g, respectively. Although no statistically remarkable differences were observed among these groups, the mortality of weaned piglets in the Diet 4 group decreased by 74.9% when compared with those in the Diet 1 group. Overall, these results indicate that a diet with reduced antibiotic levels and E. faecium supplementation (Diet 4 group) did not affect the growth of piglets.

The gut microbiota play an important role in the metabolism of hosts (Lippert et al. 2017). In the present study, reduced levels of antibiotics and E. faecium supplementation induced changes in the fecal microbiota of weaned piglets. The values of the Sobs, Chao1, ACE, and Shannon indexes in the four diet treatment groups were increased, whereas those of the Simpson index were decreased from day 1 to 14. This proves that the species richness of the community was increased over the course of the experiment. These results agree with those of Frese et al. (2015). In addition, the number of OTUs was significantly reduced in the Diet 3 group on day 14, as were the Sobs, Chao1, and ACE indexes, demonstrating that dietary supplementation with 50 mg/kg aureomycin and 9 × 105 CFU/g E. faecium decreased microbial diversity and richness. Microbiota with more diversity have been shown to maintain a more stable ecology and to be favorable for the overall health of animals (Hooper and Macpherson 2010; Hildebrand et al. 2013). Moreover, the microbial richness of heavier piglets is significantly higher than that of lighter piglets (Han et al. 2017), which indicates that microbial richness is associated with the changes in body weight. Therefore, the decreases in the microbial diversity and richness may contribute to explain the lower body weight and average daily gain of weaned piglets in the Diet 3 group. A previous study reported that the alpha diversity was significantly influenced by antibiotic intervention (Tulstrup et al. 2015). However, no changes were found in alpha diversity induced by dietary supplementation with antibiotics in the present study, which is in concord with the results of previous studies (Zhang et al. 2016; Li et al. 2017). This discrepancy could be explained by the differences in the diets and animal models used (Zhao et al. 2015). Tulstrup et al. (2015) used Wistar rats as models which received a daily dosage of 0.5 mL of antibiotic solution containing 60 mg/mL amoxicillin, 8 mg/mL cefotaxime, 8 mg/mL vancomycin and 8 mg/mL metronidazole treatment, whereas piglets are used as models fed with a diet supplemented with 75 mg/kg or 50 mg/kg aureomycin in the present study.

To further illuminate whether changes in the composition of the microbiota were associated with dietary treatment, the distributions of the bacterial community structure at phylum and genus levels were investigated. Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Spirochaetes, and Proteobacteria were the dominant phyla, which is identical to the conclusions of previous studies (Kong et al. 2016; Yan et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2016; Mu et al. 2017). In addition, the abundance of Bacteroidetes and Spirochaetes was increased whereas that of Proteobacteria was decreased from day 1 to 7, and the abundance of these phyla kept stable from day 7 to 14. A previous study demonstrated that the abundance of Bacteroidetes is associated with protein digestibility (Blackburn and Hobson 1962), and the abundance of Spirochaetes is positively correlated with apparent hemicellulose digestibility in piglets (Niu et al. 2015). These results revealed that Bacteroidetes and Spirochaetes might be involved in the digestion of protein and carbohydrate. Another important finding is that the Diet 3 group exhibited the lowest abundance of Fusobacteria, Lentisphaerae, and Planctomycetes on day 1 and the lowest abundance of Actinobacteria on day 14. These findings are similar to the statement that the abundance of Fusobacteria and Lentisphaerae in piglets feces decreased from age 28 to 150 days (Niu et al. 2015). Actinobacteria are considered to be extremely important to the health of animals because of their important roles in the production of antibiotics, antivirals, and enzymes (Newman and Cragg 2007; Tan and Liu 2017). Notably, these results indicate that in Diet 3 Group, the induced body weight loss of weaned piglets was associated with the decreased abundance of bacteria that have a positive effect on the health of hosts. Li et al. (2017) signified that dietary supplementation with 75 mg/kg aureomycin decreased the abundance of Proteobacteria, whereas no difference in the abundance of Proteobacteria was observed between the Diet 2 and Diet 1 groups in this study.

At genus level, it’s found that taxa belonging to Firmicutes, including Anaerovibrio, Coprococcus, Oscillospira, Phascolarctobacterium, and 02d06 exhibited marked differences in abundance among the four groups. Firmicutes play an important role in starch and fiber degradation (Kim et al. 2011), and increased abundance of Firmicutes is associated with obesity and the energy intake of hosts from food in humans (Turnbaugh et al. 2006; Schwiertz et al. 2010). In addition, it is shown that elevated human body weight is associated with a gut microbiota composition characterized by elevated levels of Firmicutes (Riva et al. 2017). Here, the abundance of Firmicutes was higher in the Diet 2 group than in the Diet 1 group on day 14. Conclusively, the results and findings of the present study suggest that the decrease in growth performance induced by treatment with antibiotics and 9 × 105 CFU/g E. faecium was associated with changes in the gut microbiota.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicate that growth performance in weaned piglets in Diet 4 group was not different from Diet 1 group and 2, whereas growth was reduced in Diet 3 group when compared with Diet 2 group. Taken together, it is concluded that dietary supplementation with 1.2 × 106 CFU/g E. faecium instead of partly aureomycin does not affect growth performance, but alters gut microbiota diversity of weaned piglets.

Abbreviations

- OTUs:

-

operational taxonomic units

- RDP:

-

Ribosomal Database Project

References

Abhisingha M, Dumnil J, Pitaksutheepong C (2017) Selection of potential probiotic Lactobacillus with inhibitory activity against Salmonella and fecal coliform bacteria. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 10:218–227

Andreas P, Farfan-Lopez C, Mora F, Rondon Y, Rossini M, Araque H (2016) Effect of using mannoproteins and antibiotics as growth promoters in diets for weaned piglets on performance. Revista Cientifica-Facultad De Ciencias Veterinarias 26:26–32

Bednorz C, Guenther S, Oelgeschlager K, Kinnemann B, Pieper R, Hartmann S, Tedin K, Semmler T, Neumann K, Schierack P, Bethe A, Wieler LH (2013) Feeding the probiotic Enterococcus faecium strain NCIMB 10415 to piglets specifically reduces the number of Escherichia coli pathotypes that adhere to the gut mucosa. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:7896–7904

Blackburn TH, Hobson PN (1962) Further studies on the isolation of proteolytic bacteria from the sheep rumen. J Gen Microbiol 29:69–81

Busing K, Zeyner A (2015) Effects of oral Enterococcus faecium strain DSM 10663 NCIMB 10415 on diarrhoea patterns and performance of sucking piglets. Benef Microbes 6:41–44

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R (2010) QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336

Casewell M, Friis C, Marco E, McMullin P, Phillips I (2003) The European ban on growth-promoting antibiotics and emerging consequences for human and animal health. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:159–161

Chee-Sanford JC, Aminov RI, Krapac IJ, Garrigues-Jeanjean N, Mackie RI (2001) Occurrence and diversity of tetracycline resistance genes in lagoons and groundwater underlying two swine production facilities. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:1494–1502

DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL (2006) Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5069–5072

Edgar RC (2013) UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods 10:996–998

Frese SA, Parker K, Calvert CC, Mills DA (2015) Diet shapes the gut microbiome of pigs during nursing and weaning. Microbiome 3:28

Gresse R, Chaucheyras-Durand F, Fleury MA, Van de Wiele T, Forano E, Blanquet-Diot S (2017) Gut microbiota dysbiosis in postweaning piglets: understanding the keys to health. Trends Microbiol 25:851–873

Han GG, Lee JY, Jin GD, Park J, Choi YH, Chae BJ, Kim EB, Choi YJ (2017) Evaluating the association between body weight and the intestinal microbiota of weaned piglets via 16S rRNA sequencing. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:5903–5911

Hildebrand F, Nguyen TL, Brinkman B, Yunta RG, Cauwe B, Vandenabeele P, Liston A, Raes J (2013) Inflammation-associated enterotypes, host genotype, cage and inter-individual effects drive gut microbiota variation in common laboratory mice. Genome Biol 14:R4

Hooper LV, Macpherson AJ (2010) Immune adaptations that maintain homeostasis with the intestinal microbiota. Nat Rev Immunol 10:159–169

Hu Y, Dun Y, Li S, Zhang D, Peng N, Zhao S, Liang Y (2015) Dietary Enterococcus faecalis LAB31 improves growth performance, reduces diarrhea, and increases fecal Lactobacillus number of weaned piglets. PLoS ONE 10:e0116635

Hu QL, Li SS, Zhang YW, Zhuo Z, Feng J (2017) Phytosterols on growth performance, antioxidant enzymes and intestinal morphology in weaned piglets. J Sci Food Agric 97:4629–4634

Kahrstrom CT, Pariente N, Weiss U (2016) Intestinal microbiota in health and disease. Nature 535:47

Kim M, Morrison M, Yu Z (2011) Status of the phylogenetic diversity census of ruminal microbiomes. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 76:49–63

Klingspor S, Martens H, Caushi D, Twardziok S, Aschenbach JR, Lodemann U (2013) Characterization of the effects of Enterococcus faecium on intestinal epithelial transport properties in piglets. J Anim Sci 91:1707–1718

Kong XF, Ji YJ, Li HW, Zhu Q, Blachier F, Geng MM, Chen W, Yin YL (2016) Colonic luminal microbiota and bacterial metabolite composition in pregnant Huanjiang mini-pigs: effects of food composition at different times of pregnancy. Sci Rep 6:37224

Lan RX, Kim IH (2017) Effects of dietary supplementation with a probiotic (Enterococcus faecium DSM 7134) on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, and gut health status in weaning pigs. J Sci Food Agric 98:825

Li M, Monaco MH, Wang M, Comstock SS, Kuhlenschmidt TB, Fahey GC Jr, Miller MJ, Kuhlenschmidt MS, Donovan SM (2014) Human milk oligosaccharides shorten rotavirus-induced diarrhea and modulate piglet mucosal immunity and colonic microbiota. ISME J 8:1609–1620

Li H, Liang T, Chu Q, Xu F, Li Y, Fu L, Zhou B (2017) Effects of several in-feed antibiotic combinations on the abundance and diversity of fecal microbes in weaned pigs. Can J Microbiol 63:402–410

Lippert K, Kedenko L, Antonielli L, Kedenko I, Gemeier C, Leitner M, Kautzky-Willer A, Paulweber B, Hackl E (2017) Gut microbiota dysbiosis associated with glucose metabolism disorders and the metabolic syndrome in older adults. Benef Microbes 8:545–556

Liu H, Zhang J, Zhang S, Yang F, Thacker PA, Zhang G, Qiao S, Ma X (2014) Oral administration of Lactobacillus fermentum I5007 favors intestinal development and alters the intestinal microbiota in formula-fed piglets. J Agric Food Chem 62:860–866

Magoc T, Salzberg SL (2011) FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 27:2957–2963

Mallo JJ, Rioperez J, Honrubia P (2010) The addition of Enterococcus faecium to diet improves piglet’s intestinal microbiota and performance. Livest Sci 133:176–178

Mu C, Yang Y, Su Y, Zoetendal EG, Zhu W (2017) Differences in microbiota membership along the gastrointestinal tract of piglets and their differential alterations following an early-life antibiotic intervention. Front Microbiol 8:797

Newman DJ, Cragg GM (2007) Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod 70:461–477

Niu Q, Li P, Hao S, Zhang Y, Kim SW, Li H, Ma X, Gao S, He L, Wu W, Huang X, Hua J, Zhou B, Huang R (2015) Dynamic distribution of the gut microbiota and the relationship with apparent crude fiber digestibility and growth stages in pigs. Sci Rep 5:9938

Puiman P, Stoll B, Molbak L, de Bruijn A, Schierbeek H, Boye M, Boehm G, Renes I, van Goudoever J, Burrin D (2013) Modulation of the gut microbiota with antibiotic treatment suppresses whole body urea production in neonatal pigs. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 304:G300–G310

Riva A, Borgo F, Lassandro C, Verduci E, Morace G, Borghi E, Berry D (2017) Pediatric obesity is associated with an altered gut microbiota and discordant shifts in Firmicutes populations. Environ Microbiol 19:95–105

Schwiertz A, Taras D, Schafer K, Beijer S, Bos NA, Donus C, Hardt PD (2010) Microbiota and SCFA in lean and overweight healthy subjects. Obesity 18:190–195

Sen T, Cawthon CR, Ihde BT, Hajnal A, DiLorenzo PM, de La Serre CB, Czaja K (2017) Diet-driven microbiota dysbiosis is associated with vagal remodeling and obesity. Physiol Behav 173:305–317

Siepert B, Reinhardt N, Kreuzer S, Bondzio A, Twardziok S, Brockmann G, Nockler K, Szabo I, Janczyk P, Pieper R, Tedin K (2014) Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 10415 supplementation affects intestinal immune-associated gene expression in post-weaning piglets. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 157:65–77

Sonnenburg JL, Backhed F (2016) Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535:56–64

Tan GY, Liu T (2017) Rational synthetic pathway refactoring of natural products biosynthesis in actinobacteria. Metab Eng 39:228–236

Taras D, Vahjen W, Macha M, Simon O (2006) Performance, diarrhea incidence, and occurrence of Escherichia coli virulence genes during long-term administration of a probiotic Enterococcus faecium strain to sows and piglets. J Anim Sci 84:608–617

Tulstrup MV, Christensen EG, Carvalho V, Linninge C, Ahrne S, Hojberg O, Licht TR, Bahl MI (2015) Antibiotic treatment affects intestinal permeability and gut microbial composition in Wistar rats dependent on antibiotic class. PLoS ONE 10:e0144854

Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Mahowald MA, Magrini V, Mardis ER, Gordon JI (2006) An obesity-associated gut microbiome with increased capacity for energy harvest. Nature 444:1027–1031

van den Bogaard AE, Stobberingh EE (2000) Epidemiology of resistance to antibiotics: links between animals and humans. Int J Antimicrob Agents 14:327–335

Vondruskova H, Slamova R, Trckova M, Zraly Z, Pavlik I (2010) Alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters in prevention of diarrhoea in weaned piglets: a review. Vet Med 55:199–224

Wang AN, Cai CJ, Zeng XF, Zhang FR, Zhang GL, Thacker PA, Wang JJ, Qiao SY (2013) Dietary supplementation with Lactobacillus fermentum I5007 improves the anti-oxidative activity of weanling piglets challenged with diquat. J Appl Microbiol 114:1582–1591

Wang YB, Du W, Fu AK, Zhang XP, Huang Y, Lee KH, Yu K, Li WF, Li YL (2016) Intestinal microbiota and oral administration of Enterococcus faecium associated with the growth performance of new-born piglets. Benef Microbes 7:529–538

Wei HK, Xue HX, Zhou ZX, Peng J (2017) A carvacrol–thymol blend decreased intestinal oxidative stress and influenced selected microbes without changing the messenger RNA levels of tight junction proteins in jejunal mucosa of weaning piglets. Animal 11:193–201

Yan H, Diao H, Xiao Y, Li W, Yu B, He J, Yu J, Zheng P, Mao X, Luo Y, Zeng B, Wei H, Chen D (2016) Gut microbiota can transfer fiber characteristics and lipid metabolic profiles of skeletal muscle from pigs to germ-free mice. Sci Rep 6:31786

Yu M, Zhang C, Yang Y, Mu C, Su Y, Yu K, Zhu W (2017) Long-term effects of early antibiotic intervention on blood parameters, apparent nutrient digestibility, and fecal microbial fermentation profile in pigs with different dietary protein levels. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 8:60

Zeng B, Zhao J, Guo W, Zhang S, Hua Y, Tang J, Kong F, Yang X, Fu L, Liao K, Yu X, Chen G, Jin L, Shuai S, Yang J, Si X, Ning R, Mishra S, Li Y (2017) High-altitude living shapes the skin microbiome in humans and pigs. Front Microbiol 8:1929

Zeyner A, Boldt E (2006) Effects of a probiotic Enterococcus faecium strain supplemented from birth to weaning on diarrhoea patterns and performance of piglets. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr 90:25–31

Zhang D, Ji H, Liu H, Wang S, Wang J, Wang Y (2016) Changes in the diversity and composition of gut microbiota of weaned piglets after oral administration of Lactobacillus or an antibiotic. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:10081–10093

Zhao W, Wang Y, Liu S, Huang J, Zhai Z, He C, Ding J, Wang J, Wang H, Fan W, Zhao J, Meng H (2015) The dynamic distribution of porcine microbiota across different ages and gastrointestinal tract segments. PLoS ONE 10:e0117441

Authors’ contributions

CH conceived and designed the study. WX, XL, XZ, KL, and JL contributed to experimental design and data analysis. CH contributed to manuscript preparation and manuscript editing. YL conducted experimental studies and statistical analysis. BD and JD edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental design and procedures in this study were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the College of Animal Science of South China Agricultural University.

Funding

This study was supported by the Project of Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (2017A030310398) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31790411).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional file

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Sample-based rarefaction analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, C., Xing, W., Liu, X. et al. Effects of dietary supplementation of probiotic Enterococcus faecium on growth performance and gut microbiota in weaned piglets. AMB Expr 9, 33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0755-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0755-z