Abstract

Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) leads to food poisoning by causing hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic uremic syndrome. Some STEC produce Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1) and/or Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2), a relatively stable protein toxin, necessitating the development of an efficient inactivation method. Here we applied a nitrogen gas plasma apparatus to the inactivation of Stx. Samples of Stx1 and Stx2 were treated with a nitrogen gas plasma generated by a plasma device using a short high-voltage pulse applied by a static induction thyristor power supply at 1.5 kpps (kilo pulse per second). The recovered Stx samples were then analyzed for immunological and biological activities. Immunochromatography demonstrated that Stx1 and Stx2 were degraded by the gas plasma. Quantification by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) showed that both toxins were efficiently degraded to less than 1/10th of their original concentration within 5 min of treatment. Western blotting further showed the gas plasma treatment degraded the A subunit, which mediates the toxicity of Stx. Moreover, an assay using HEp-2 cells as an index of cytotoxicity showed that gas plasma treatment reduced the toxic activity of Stx. Therefore, nitrogen gas plasma might be an efficient method for the inactivation of Stx.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The virulence of Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), such as E. coli O157:H7 and other serotypes, including their most dangerous subset, enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), depends on the production of Stx (Gyles 2007; Hunt 2010). The toxins inhibit protein synthesis and are therefore deleterious to humans, leading to life-threating complications including hemorrhagic colitis (HC) and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) (Boerlin et al. 1999; Scallan et al. 2011). These illnesses are known as food-borne diseases, resulting from the ingestion of food contaminated with STEC and their toxins. To improve the quality and safety of the food supply, it is necessary to minimize toxic compounds in foods. Thus, technologies to degrade and/or inactivate Stx are needed.

Stx produced by STEC comprise two major groups; namely, Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1) and Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2). Stx1 has identical characteristics to Stx produced by Shigella dysenteriae in terms of immunological, physical, chemical, and biological properties (Takao et al. 1988). Stx2 has 55% nucleotide sequence identity to Stx1 but differs substantially in its physiological properties (Jackson et al. 1987; Scotland et al. 1985). Stx1 and Stx2 each comprise an A subunit monomer, which plays a role in toxicity, and a pentamer of B subunits, which are involved in binding to a cellular receptor, globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) (Lingwood et al. 1987; Stein et al. 1992; Fraser et al. 1994). Stx2 is known to be highly virulent, and is several orders of magnitude more toxic than Stx1 (Nataro and Kaper 1998; Pickering et al. 1994; Manning et al. 2008). Furthermore, Stx2 is relatively heat stable and is not inactivated by pasteurization (Rasooly and Do 2010).

Several compounds have been reported to inhibit Stx1 and Stx2 (Sugita-Konishi et al. 1999; Kulkarni et al. 2010; Rasooly et al. 2010; Quinones et al. 2009; Friedman et al. 2013). However, it remains unclear whether these anti-Stx1 and anti-Stx2 compounds cause irreversible inactivation or whether they have indirect effects, such as inhibiting toxin release or affecting the digestive tract of the host (Friedman and Rasooly 2013).

Recently, the effectiveness of gas plasma technology in eradicating various types of microbes such as viruses, bacteria and fungi has been demonstrated (Fridman 2012; Laroussi et al. 2012; Shintani et al. 2010). In this regard, gas plasma technology is a promising method for achieving disinfection and sterilization in a broad range of applications. In particular, gas plasma technology provides an excellent platform for food control, preventing the spread of harmful microbes. For example, Schlüter’s group has demonstrated inactivation of Stx-producing E. coli using an atmospheric pressure plasma jet (Baier et al. 2015).

The gas plasma can be artificially generated by various types of discharge, including arc, corona, direct current, glow, high/low frequency, micro, pulse, and streamer. Further developments in gas plasma technology are likely to enable broader applications including the detoxification of toxins. Although Park’s group and others have worked on the inactivation of lipopolysaccharide using a different technology for producing gas plasma (Park et al. 2007; Shintani et al. 2007), there are no reports showing the inactivation of Stx using gas plasma.

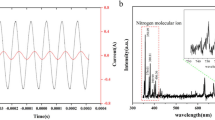

Recently, we successfully generated nitrogen gas plasma by applying a short-time high-voltage pulse to nitrogen gas as an inert gas, using a static induction (SI) thyristor power supply (Sakudo et al. 2013a). Bacterial spores, vegetative bacteria, and viruses are all inactivated by the nitrogen gas plasma (Sakudo et al. 2014; Maeda et al. 2015). Several factors contribute to the thermal and non-thermal mechanism of inactivation, such as heat, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and reactive chemical species generated during operation of the nitrogen gas plasma device. Among them, reactive chemical species may be the most important factor for inactivation of bacteria and viruses (Maeda et al. 2015; Sakudo et al. 2017).

Here, based on these previous observations, we have extended our research to examine the potential use of nitrogen gas plasma for the inactivation of Stx. The effect of nitrogen gas plasma treatment on Stx was investigated by biochemical analyses and a bioassay using cell culture. The potential mechanisms of Stx inactivation by the gas plasma are then discussed.

Materials and methods

Exposure of Stx samples to gas plasma

Stx1 from E. coli O157:H7 and Stx2 from E. coli O157:H7, which were solubilized at 0.1 mg/ml in 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.6), 0.1 M NaCl, 0.001% polyvinyl alcohol after purification by affinity chromatography using Gb3 and 0.45 μm filtration, were purchased from Nakalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). The Stx1 and Stx2 solutions were each diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to 1 μg/ml, and a 20 μl aliquot was dropped onto a coverslip (24 mm × 60 mm Thickness No. 1, 0.12–0.17 mm, Matsunami Glass Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan) and air-dried. The nitrogen gas plasma was produced by a BLP-TES (bi-polar and low-pressure plasma-triple effects sterilization) device (NGK Insulators, Ltd.) using a short-time high-voltage pulse generated by an SI thyristor, which was used as a pulsed power supply. The coverslip containing the Stx samples was placed in the device’s chamber on a grid of electrodes, comprising a cathode electrode (earth electrode) between two anode electrodes (high voltage electrodes). The chamber box was then decompressed and degassed, and nitrogen gas (99.9995%, Okano, Okinawa, Japan) was introduced at a flow rate of approximately 10 L/min. The pressure in the box was maintained at about 0.5 atmospheres, and the plasma was discharged at 0–1.5 kpps (kilo pulse per second). Nitrogen gas plasma-treated and control untreated samples were recovered from the coverslip by reconstitution in 20 μl of PBS. The recovered solutions were subjected to biochemical and immunological analysis.

Immunochromatography

Stx1 and Stx2 in the recovered samples were detected by immunochromatography using the NH Immunochromato VT1/2 kit (NH Foods Ltd., Osaka, Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The kit produces two lines: development of a control line indicates that the strip has functioned properly, whereas development of a test line indicates the presence of Stx1 or Stx2. The kit can detect Stx1 at 2.5 ng/ml, and Stx2 at 1.25 ng/ml (Yonekita et al. 2012).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Stx1 and Stx2 in the recovered samples were quantified by using an ELISA kit, RIDASCREEN® Verotoxin (R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of Stx1 and Stx2 was quantified by measuring absorbance at 450 nm relative to respective Stx1 and Stx2 standards.

Calculation of the detection limit

The limit of detection in the ELISA was calculated according to Miller’s study (Miller and Miller 2010). Equation 1 defines the detection limit (y), which indicates whether a sample contains a certain Stx based on the average (y B) and standard deviation (SB) of the signal from a blank control (signal of samples without Stx). The calculated intercept is used as an estimate of y B. Equation 2 is used to estimate SB, or statistics S y/x , which estimates the random error in the y direction (Miller and Miller 2010). The ŷ i values are the points corresponding to the individual x values on the calculated regression line:

Western blotting

Each recovered sample was added to an equal volume of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel-loading buffer [90 mM Tris–HCl (pH 6.8), 10% mercaptoethanol, 2% SDS, 0.02% bromophenol blue, and 20% glycerol] and boiled for 5 min. The proteins were then resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) before being electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Hybond-P; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA) for 60 min at 15 V. Blots were treated with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated with a rabbit polyclonal anti-Stx1 antibody (Cat No. 64-025, BioAcademia, Osaka, Japan) or a mouse monoclonal anti-Stx2 antibody (Cat No. 20273-04, Nakalai Tesque) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and 0.5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS-T, the membrane was incubated in horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) in PBS-T and 0.5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS-T, the proteins were detected by using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) and an Ez-Capture MG imaging system (ATTO Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Cell assay

The activity of Stx1 and Stx2 was measured by previously described methods (Jones et al. 2000) with slight modification. In brief, the index of cytotoxic activity of Stx1 and Stx2 was measured in HEp-2 cells, cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (MEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). The recovered Stx samples were 50-fold diluted with serum-free MEM and then added to 1 × 104 HEp-2 cells at 100 μl/well in a 96-well microtiter plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h for Stx1 and for 48 h for Stx2, cell viability was measured by using the Cell Counting kit-8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, 10 μl of cell counting kit-8 solution was added to the microplate, which was then incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Absorbance was determined at 450 nm relative to a reference wavelength of 630 nm using a microplate reader (Model 680; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis of differences was performed by non-repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Bonferroni correction.

Results

To investigate the effect of nitrogen gas plasma on Stx, 20 μl of a 1 μg/ml solution of Stx1 or Stx2 was spotted onto a coverslip, which was placed on the earth electrode of the BLP-TES device, and subjected to nitrogen gas plasma treatment (1.5 kpps, 0, 5, 15, and 30 min). Stx1 and Stx2 were then recovered from the treated spots, and subjected to various analyses.

First, the treated Stx1 and Stx2 were subjected to immunochromatography (Fig. 1). The results showed that the test lines of Stx1 were diminished by gas plasma treatment for 5, 15 and 30 min, as compared with the untreated sample (0 min) (Fig. 1a). In the case of Stx2, test lines were detected in the untreated sample (0 min) and the sample treated for 5 min, but were diminished in samples treated for 15 and 30 min (Fig. 1b).

Immunochromatography of Shiga toxin 1 (Stx1) and Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2) after nitrogen gas plasma treatment. A coverslip containing dried spots from 20 μl aliquots of a 1 μg/ml solution of Shiga toxins (Stx) including Stx1 (a) and Stx2 (b) was treated with nitrogen gas plasma using a bi-polar and low-pressure plasma-triple effects sterilization (BLP-TES) device (1.5 kpps) for 0, 5, 15, or 30 min. The recovered Stx1 and Stx2 samples were analyzed by immunochromatography using an NH immunochromato VT1/2 kit (NH Foods Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Test lines for Stx1 and Stx2, and reference lines for the internal control are indicated by arrows

Next, the gas plasma-treated Stx1 and Stx2 samples were subjected to ELISA (Fig. 2), which provides a quantitative and more sensitive and accurate analysis than immunochromatography. The detection limit of the ELISA was calculated to be 0.3279 ng/ml for Stx1 and 0.6540 ng/ml for Stx2. The results of the ELISA (mean ± standard deviation) showed that the treatment of Stx1 and Stx2 with nitrogen gas plasma at 1.5 kpps decreased the toxin levels by more than 90%: Stx1 decreased from 351.98 ± 19.20 ng/ml at 0 min of treatment to 21.24 ± 0.65 ng/ml at 5 min of treatment, and Stx2 decreased from 633.56 ± 16.33 ng/ml at 0 min to 4.27 ± 0.91 ng/ml at 5 min. Plasma gas treatment for 15 min led to 5.60 ± 1.14 ng/ml of Stx1 and 6.18 ± 3.38 ng/ml of Stx2, whereas that for 30 min led to 6.03 ± 1.84 ng/ml of Stx1 and 3.71 ± 1.13 ng/ml of Stx2. Thus, the concentration of Stx1 and Stx2 at 5, 15, and 30 min was almost at the detection limit of the ELISA assay.

Quantitative measurement of Stx1 and Stx2 by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) after nitrogen gas plasma treatment. A coverslip containing dried spots from 20 μl aliquots of a 1 μg/ml solution of Stx1 (a) and Stx2 (b) was treated with nitrogen gas plasma using BLP-TES device (1.5 kpps) for 0, 5, 15, and 30 min. The recovered samples were subjected to ELISA using RIDASCREEN® Verotoxin (R-Biopharm AG, Darmstadt, Germany) to quantify Stx1 and Stx2. Values were considered significantly different from the untreated control (0 min) when verified by non-repeated measures ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni correction (**p < 0.01)

Western blotting was also performed to investigate the effect of nitrogen gas plasma on Stx1 and Stx2 (Fig. 3). This analysis showed that the band corresponding to the A subunit of Stx1 (approximately 35 kDa) and Stx2 (approximately 35 kDa) (Russo et al. 2014) diminished after nitrogen gas plasma treatment for 5, 15, and 30 min, as compared with that of the untreated sample (0 min).

Western blotting of Stx1 and Stx2 after nitrogen gas plasma treatment. A coverslip containing dried spots from 20 μl aliquots of a 1 μg/ml solution of Stx1 (a) and Stx2 (b) was treated with nitrogen gas plasma using BLP-TES device (1.5 kpps) for 0, 5, 15, or 30 min. The recovered samples were subjected to Western blotting using antibody recognizing the A subunit of Stx

The observation of Stx1 degradation by gas plasma treatment was further supported by a cell assay (Fig. 4). Because Stx1 and Stx2 have cytotoxic activity against HEp-2 cells, the change in cell viability after incubation with the treated samples was used as an index of the activity of Stx1 and Stx2. The viability of cells incubated with untreated Stx1 (0 min in Fig. 4a) and Stx2 (0 min in Fig. 4b) was lower than that of cells incubated with gas plasma-treated samples, suggesting that the cytotoxic activity of Stx1 and Stx2 was reduced by increasing plasma treatment. Notably, cells incubated with samples subjected to gas plasma treatment for 30 min showed significantly higher viability as compared with cells incubated with untreated samples (p < 0.05 for Stx1; p < 0.01 for Stx2). Therefore, nitrogen gas plasma treatment causes not only the degradation of Stx1 and Stx2, but also a reduction of their physiological activity.

Decreasing cell toxicity of Stx1 and Stx2 after nitrogen gas plasma treatment. A coverslip containing dried spots from 20 μl aliquots of a 1 μg/ml solution of Stx1 (a) and Stx2 (b) was treated with nitrogen gas plasma using BLP-TES device (1.5 kpps) for 0, 1, 2, 5, 15, and 30 min. The recovered samples were diluted 50-fold with minimum essential medium (MEM) and then added to HEp-2 cells at 100 μl/well in a microtiter plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 h for Stx1 and for 48 h for Stx2, the viability of HEp-2 cells was monitored using a Cell counting kit 8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). The activity of Stx, which was measured on the basis of cell toxicity of Stx to HEp-2 cells, was significantly inhibited, as compared with no treatment (0 min), by 30 min of nitrogen gas plasma treatment using BLP-TES (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

Discussion

The potential use of physical methods to degrade Stx can be exploited to improve food safety. Here, the potential application of nitrogen gas plasma to degrade Stx has been studied using a BLP-TES device. The maximum temperature in the chamber box of the BLP-TES device was 42 °C at 5 min, 70 °C at 15 min, and 75 °C at 30 min (Sakudo et al. 2013b). Our study shows that during inactivation of Stx1 and Stx2 by the BLP-TES device, the sample temperature did not increase above 80 °C even after prolonged exposure for 30 min. Burk et al. (2003) previously showed that heat treatment above 80 °C for 10 min can be used to inactivate Stx. A more recent study reported only a slight decrease in activity of Stx2 after heat treatment at 60 °C for 1 h, although a significant reduction in activity was observed after treatment at 80 °C for 1 h (He et al. 2012). As the effective temperature for inactivation is close that seen during gas plasma treatment using the BLP-TES device, detailed quantitative and comparative studies are required to ascertain whether the inactivation mechanism of the gas plasma involves heat.

However, so far, the main mechanism of inactivation using the nitrogen gas plasma system of the BLP-TES device does not appear to involve exposure of the sample to elevated temperatures. A previous observation has suggested that the conformational changes in a protein induced by the nitrogen gas plasma are mediated by mechanisms distinct from those of heat degradation (Sakudo et al. 2013a). Because Stx1 and Stx2 are proteins, the conformational changes and degradation caused by the gas plasma may play important roles in their inactivation. In addition, the use of a more sensitive cell assay for Stx would be likely to detect the inactivating effect of the gas plasma on Stx at an earlier treatment time, because efficient degradation of Stx1 and Stx2 within 5 or 15 min of treatment was shown by all biochemical assays, including immunochromatography, ELISA, and Western blotting. Thus, further analysis using sensitive bioassays is required.

The Stx1 and Stx2 antibodies used in the Western blotting analysis recognize the A subunit of each toxin. The Western blotting data therefore suggest that the nitrogen gas plasma degrades the A subunit of Stx, which is known to elicit its toxic activity. Therefore, some factors generated during operation of the BLP-TES device such as the production of reactive chemical species, which have previously been shown to be the principal contributing reason for the inactivation of bacteria and viruses (Maeda et al. 2015; Sakudo et al. 2017), may be responsible for degrading Stx and their A subunits. Additional clarification of the mechanisms by which nitrogen gas plasma degrades Stx are required. Furthermore, in the present study, effective degradation of Stx was observed when a coverslip was used as the surface matrix during gas plasma treatment. Because the degradation efficiency and mechanisms may depend on the materials used for the surface matrix, further studies using other surface materials should be performed.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- BLP-TES:

-

bi-polar and low-pressure plasma-triple effects sterilization

- BRAIN:

-

Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- EHEC:

-

enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli

- ELISA:

-

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FCS:

-

fetal calf serum

- Gb3:

-

globotriaosylceramide

- HC:

-

hemorrhagic colitis

- HRP:

-

horseradish peroxidase

- HUS:

-

hemolytic uremic syndrome

- MEM:

-

minimum essential medium

- PAGE:

-

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PBS:

-

phosphate-buffered saline

- PBS-T:

-

PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20

- PVDF:

-

polyvinylidene difluoride

- SDS:

-

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- SI:

-

static induction

- STEC:

-

Stx-producing Escherichia coli

- Stx:

-

Shiga toxin

- Stx1:

-

Shiga toxin 1

- Stx2:

-

Shiga toxin 2

- UV:

-

ultraviolet

References

Baier M, Janssen T, Wieler LH, Ehlbeck J, Knorr D, Schlüter O (2015) Inactivation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 using cold atmospheric pressure plasma. J Biosci Bioeng 120(3):275–279. doi:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.01.003

Boerlin P, McEwen SA, Boerlin-Petzold F, Wilson JB, Johnson RP, Gyles CL (1999) Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J Clin Microbiol 37:497–503

Burk C, Dietrich R, Acar G, Moravek M, Bulte M, Martlbauer E (2003) Identification and characterization of a new variant of Shiga toxin 1 in Escherichia coli ONT:H19 of bovine origin. J Clin Microbiol 41(5):2106–2112

Fraser ME, Chernaia MM, Kozlov YV, James MN (1994) Crystal structure of the holotoxin from Shigella dysenteriae at 2.5 A resolution. Nat Struct Biol 1(1):59–64

Fridman A (2012) Plasma chemistry. Cambridge University Press, London

Friedman M, Rasooly R (2013) Review of the inhibition of biological activities of food-related selected toxins by natural compounds. Toxins (Basel) 5(4):743–775. doi:10.3390/toxins5040743

Friedman M, Henika PR, Levin CE (2013) Bactericidal activities of health-promoting, food-derived powders against the foodborne pathogens Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella enterica, and Staphylococcus aureus. J Food Sci 78(2):M270–M275. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12021

Gyles CL (2007) Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. J Animal Sci 6:45–62

He X, Quiñones B, McMahon S, Mandrell RE (2012) A single-step purification and molecular characterization of functional Shiga toxin 2 variants from pathogenic Escherichia coli. Toxins (Basel) 4:487–504. doi:10.3390/toxins4070487

Hunt JM (2010) Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC). Clin Lab Med 30(1):21–45. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2009.11.001

Jackson MP, Neil RJ, O’Brien AD, Holmes RK, Newland JW (1987) Nucleotide sequence analysis and comparison of the structural genes for Shiga-like toxin I and Shiga-like toxin II encoded by bacteriophages from Escherichia coli 933. FEMS Microbiol Lett 44:109–114

Jones NL, Islur A, Haq R, Mascarenhas M, Karmali MA, Perdue MH, Zanke BW, Sherman PM (2000) Escherichia coli Shiga toxins induce apoptosis in epithelial cells that is regulated by the Bcl-2 family. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 278(5):G811–G819

Kulkarni AA, Fuller C, Korman H, Weiss AA, Iyer SS (2010) Glycan encapsulated gold nanoparticles selectively inhibit Shiga toxins 1 and 2. Bioconjug Chem 21(8):1486–1493. doi:10.1021/bc100095w

Laroussi M, Kong MG, Morfill G, Stolz W (2012) Plasma medicine: applications of low-temperature gas plasmas in medicine and biology. Cambridge University Press, London

Lingwood CA, Law H, Richardson S, Petric M, Brunton JL, De Grandis S, Karmali M (1987) Glycolipid binding of purified and recombinant Escherichia coli produced verotoxin in vitro. J Biol Chem 262(18):8834–8839

Maeda K, Toyokawa Y, Shimizu N, Imanishi Y, Sakudo A (2015) Inactivation of Salmonella by nitrogen gas plasma generated by a static induction thyristor as a pulsed power supply. Food Control 52:54–59

Manning SD, Motiwala AS, Springman AC, Qi W, Lacher DW, Ouellette LM, Mladonicky JM, Somsel P, Rudrik JT, Dietrich SE, Zhang W, Swaminathan B, Alland D, Whittam TS (2008) Variation in virulence among clades of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with disease outbreaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(12):4868–4873. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710834105

Miller JN, Miller JC (2010) Statistics and Chemometrics for Analytical Chemistry, 6th edn. Pearson Education Canada, Toronto

Nataro JP, Kaper JB (1998) Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev 11(1):142–201

Park BJ, Takatori K, Lee MH, Han DW, Woo YI, Son HJ, Kim JK, Chung KH, Hyun SO, Park JC (2007) Escherichia coli sterilization and lipopolysaccharide inactivation using microwave-induced argon plasma at atmospheric pressure. Surf Coat Technol 201:5738–5741

Pickering LK, Obrig TG, Stapleton FB (1994) Hemolytic-uremic syndrome and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Pediatr Infect Dis J 13(6):459–475

Quinones B, Massey S, Friedman M, Swimley MS, Teter K (2009) Novel cell-based method to detect Shiga toxin 2 from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and inhibitors of toxin activity. Appl Environ Microbiol 75(5):1410–1416. doi:10.1128/AEM.02230-08

Rasooly R, Do PM (2010) Shiga toxin Stx2 is heat-stable and not inactivated by pasteurization. Int J Food Microbiol 136(3):290–294. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.10.005

Rasooly R, Do PM, Levin CE, Friedman M (2010) Inhibition of Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2) in apple juices and its resistance to pasteurization. J Food Sci 75(5):M296–M301. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2010.01615.x

Russo LM, Melton-Celsa AR, Smith MJ, O’Brien AD (2014) Comparisons of native Shiga toxins (Stxs) type 1 and 2 with chimeric toxins indicate that the source of the binding subunit dictates degree of toxicity. PLoS ONE 9(3):e93463. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093463

Sakudo A, Higa M, Maeda K, Shimizu N, Imanishi Y, Shintani H (2013a) Sterilization mechanism of nitrogen gas plasma: induction of secondary structural change in protein. Microbiol Immunol 57(7):536–542. doi:10.1111/1348-0421.12061

Sakudo A, Shimizu N, Imanishi Y, Ikuta K (2013b) N2 gas plasma inactivates influenza virus by inducing changes in viral surface morphology, protein, and genomic RNA. Biomed Res Int 2013:694269. doi:10.1155/2013/694269

Sakudo A, Misawa T, Shimizu N, Imanishi Y (2014) N2 gas plasma inactivates influenza virus mediated by oxidative stress. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 6:69–79

Sakudo A, Toyokawa Y, Imanishi Y, Murakami T (2017) Crucial roles of reactive chemical species in modification of respiratory syncytial virus by nitrogen gas plasma. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 74:131–136. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.007

Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM (2011) Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 17(1):7–15. doi:10.3201/eid1701.091101p1

Scotland SM, Smith HR, Rowe B (1985) Two distinct toxins active on Vero cells from Escherichia coli O157. Lancet 2(8460):885–886

Shintani H, Shimizu N, Imanishi Y, Sekiya T, Tamazawa K, Taniguchi A, Kido N (2007) Inactivation of microorganisms and endotoxins by low temperature nitrogen gas plasma exposure. Biocontrol Sci 12(4):131–143

Shintani H, Sakudo A, Burke P, McDonnell G (2010) Gas plasma sterilization of microorganisms and mechanisms of action. Exp Ther Med 1(5):731–738. doi:10.3892/etm.2010.136

Stein PE, Boodhoo A, Tyrrell GJ, Brunton JL, Read RJ (1992) Crystal structure of the cell-binding B oligomer of verotoxin-1 from E. coli. Nature 355(6362):748–750. doi:10.1038/355748a0

Sugita-Konishi Y, Hara-Kudo Y, Amano F, Okubo T, Aoi N, Iwaki M, Kumagai S (1999) Epigallocatechin gallate and gallocatechin gallate in green tea catechins inhibit extracellular release of Vero toxin from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Biochim Biophys Acta 1472(1–2):42–50

Takao T, Tanabe T, Hong YM, Shimonishi Y, Kurazono H, Yutsudo T, Sasakawa C, Yoshikawa CM, Takeda Y (1988) Identity of molecular structure of shiga-like toxin I (VT1) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 with that of shiga toxin. Microb Pathog 5:357–369

Yonekita T, Terao Y, Hojo E, Morishita N, Mastumoto T (2012) Development of an immunochromatographic kit for rapid detection of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli and vero toxin1/2. Res J Food Agric 35:49–52

Authors’ contributions

AS performed experiments, conceived of the study, designed experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the manuscript. YI made a substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data presented. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Naohiro Shimizu (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan) and Mr. Yoichi Toyokawa (University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan) for technical support. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for the Promotion of Basic Research Activities for Innovative Biosciences from the Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (BRAIN), the Science and Technology Research Promotion Program for Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries and Food Industry, a Grant-in-Aid from Amano Institute of Technology, a Grant-in-Aid from Uruma Academic Research Fund, and Grant-in-Aids for Scientific Research (Nos. 22110514, 24110717, and 16K04997) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science as well as a Grant-in-Aid from the Tojuro Iijima Foundation for Food Science and Technology.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data were included in the main manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding

This study was funded by the Bio-oriented Technology Research Advancement Institution (BRAIN), the Science and Technology Research Promotion Program for Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries and Food Industry, Amano Institute of Technology, Uruma Academic Research Fund, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Numbers 22110514, 24110717, and 16K04997) as well as the Tojuro Iijima Foundation for Food Science and Technology.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sakudo, A., Imanishi, Y. Degradation and inactivation of Shiga toxins by nitrogen gas plasma. AMB Expr 7, 77 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-017-0380-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-017-0380-7