Abstract

Background

Evidence suggests that epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is closely related to coronary artery stenosis (CAS). However, sexual dimorphism may be present in adipose tissue, and its influence on CAS between men and women is controversial. We assessed the relationship between EAT and CAS by sex and menopausal status in patients with suspected angina.

Methods

Six hundred twenty-eight consecutive patients (men/women n = 257/371; mean age = 59.9 ± 10.2 years) who had chest pain for angina and underwent coronary angiography were included. CAS was defined as > 50% luminal narrowing of at least one epicardial coronary artery. EAT thickness was measured by transthoracic echocardiography.

Results

Of the 628 patients, 52.1% (n = 134) of men and 35.3% (n = 131) of women had CAS. The mean EAT thickness was not different between men and women and was larger in patients with CAS (8.04 ± 2.39 vs 6.58 ± 1.88 mm, P < 0.001). EAT thickness was independently associated with CAS in both sexes (P < 0.001). The odds ratio (OR) of EAT for the presence of CAS was higher in men (OR = 1.43, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.21–1.69) than in women (OR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.10–1.40). EAT thickness was larger in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal women (7.59 ± 2.25 vs 5.80 ± 1.57 mm, P < 0.001) and was independently related with CAS (OR = 1.24, 95% CI 1.09–1.41). This was not the case in premenopausal women.

Conclusion

In patients with suspected angina, an increase in EAT thickness was independently related to the presence of CAS in both men and women, with it being stronger in men. According to menopausal status in women, EAT thickness is significantly associated with CAS only in postmenopausal women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Growing evidence suggests that epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) is closely related to coronary artery stenosis (CAS). EAT is an emerging cardiometabolic risk factor due to the close proximity to the coronary artery and heart and its secretion of proatherogenic and proinflammatory adipokines [1]. EAT has a close relationship with metabolic syndromes, coronary atherosclerosis, and myocardial function [2,3,4].

Sexual dimorphism in adipose tissue deposits is well documented in humans [5]. Premenopausal women tend to accumulate subcutaneous adipose tissue, which is located primarily in the gluteal and femoral regions, whereas men accrue more visceral fat, which is closely related to increased metabolic and cardiovascular risk [5, 6]. After menopause, fat redistribution favoring visceral fat deposits occurs, and this shift leads to a parallel increase of cardiometabolic risk in women [7].

However, the sex difference of the association between EAT and CAS has not been thoroughly studied, and the results are still controversial. The menopausal transition in women is thought to be associated with changes in body fat deposition and composition rather than weight gain [8, 9]. The prevalence of EAT in postmenopausal women was greater than that of premenopausal women, independent of age, race, obesity, and other factors related to EAT [10, 11]. Therefore, the impact of EAT on cardiovascular structure and function in women could be different to menopausal status. The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between EAT and CAS by sex and menopausal status in patients with chest pain and are undergoing coronary angiography.

Methods

Study population

Six hundred twenty-eight consecutive patients (men/women = 257/371; mean age = 59.9 ± 10.2 years) were included for this study, who had visited the outpatient clinic for chest pain with suspected angina. This study was a part of the Korean Women’s Chest Pain Multicenter Registry data (KoROSE), which is a nation-wide multicenter registry, which is participating in 20 tertiary hospitals in Korea. Twenty- to 80-year-old patients presenting with chest pain, or other symptoms indicative of myocardial ischemia, were included if their coronary status had been evaluated [12]. Patients with previously confirmed coronary artery disease, significant valvular or structural heart disease, and significant medical diseases were excluded. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board in each center. The written informed consent for registration was obtained from each patient.

Data collection

In each patient, laboratory tests, transthoracic echocardiography, and invasive coronary angiography (CAG) were performed within a 1-month interval. Hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia were defined if the patient was previously diagnosed or had taken related medications. Furthermore, the patients were newly diagnosed with dyslipidemia if their lipid profiles met the criteria of dyslipidemia, according to the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guideline [13]. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30. Menopausal status was assessed via a self-reported questionnaire. The invasive CAG was performed using a standard method in each patient. The severity of CAS was assessed by interventional cardiologists of each institute in a blind condition to the EAT data and concept of this study. Obstructive CAS was defined as the presence of > 50% luminal narrowing in at least one coronary artery.

Measurement of EAT thickness

EAT thickness was measured with transthoracic echocardiography, using commercially available equipment (Vivid 7 and 9, General Electric Medical Health, Waukesha, WI; iE33, Philips Medical, Andover, MA). EAT thickness was measured as the maximal thickness of echo-free space from the right ventricular free wall to the visceral pericardium, in parasternal long-axis images at end-systole, using the aortic annulus as an anatomic landmark [14]. The intra-observer variability and inter-observer variability for EAT thickness measurement were excellent (interclass correlation coefficient [ICC] = 0.986, 95% confidence intervals [CI] 0.983–0.988, P < 0.001 and ICC = 0.898, 95% CI 0.788–0.951, P < 0.001, respectively).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were presented as a mean ± standard deviation, and categorical data were expressed as numbers and percentages. To compare the two groups, a paired t test was used for continuous variables, and a chi-squared test was used for categorical variables. The analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to compare mean EAT thicknesses, after adjusting for related factors of EAT that had been previously reported, including age, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and BMI [15,16,17]. The estimated marginal mean of EAT thickness by ANCOVA was presented as a mean ± standard error, after adjusting for related factors of EAT. Univariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between coronary artery disease and the clinical risk factors and EAT. Also, to assess the sex difference’s effect of EAT on the presence of CAS, the interactive effect of sex × EAT thickness was examined using binary logistic regression. Age, BMI, and EAT thickness were used as continuous variables, and smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia were used as categorical variables for regression analysis. The interactive plots were generated by ggplot2 R packages. The predictive value of EAT thickness for CAS was tested via receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. The cutoff point was selected using the value which had a maximum Youden’s index. Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value of < 0.05 using 95% CIs. All analyses except the interactive plot were conducted using the SPSS for Windows version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of patients are presented in Table 1. Men were younger than women. The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia and a familial history of coronary artery disease were not significantly different between men and women. However, the prevalence of smoking was higher in men. In laboratory findings, the levels of low-density lipoprotein and triglycerides were higher in men, whereas the level of high-density lipoprotein was higher in women. The presence of CAS was more frequent in men than in women (P < 0.001).

In women, 312 patients (84.1%) were postmenopausal. Among them, only 7 patients (2% of postmenopausal women) took hormonal replacement therapy. Although BMI was not significantly different between pre- and postmenopausal women, waist circumference was larger in postmenopausal women. The prevalence of hypertension and diabetes was higher in postmenopausal women. In laboratory findings, lipid profiles were not different between pre- and postmenopausal women, but high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) levels were higher in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal women (P = 0.04). The presence of CAS was more prevalent in postmenopausal women than in premenopausal women (P = 0.001).

Comparison of the relationship between EAT thickness and CAS by the sex

In a total of 628 patients, the mean EAT thickness was 7.21 ± 2.23 mm. EAT thickness weakly, but positively, correlated with age (r = 0.28, P < 0.001). EAT thickness was larger in patients with hypertension (7.66 ± 2.34 vs 6.80 ± 2.05 mm, P < 0.001) and in patients with diabetes (7.81 ± 2.38 vs 7.08 ± 2.18 mm, P = 0.002) but not in patients with dyslipidemia (P = 0.169). BMI had a weak relationship with EAT thickness (r = 0.12, P = 0.003).

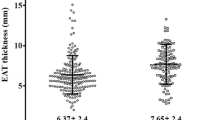

EAT thickness was larger in patients with CAS than in patients without CAS (8.04 ± 2.39 mm vs 6.58 ± 1.88 mm, P < 0.001). An analysis according to dividing sex, EAT thickness was not different between men and women (7.05 ± 2.20 vs 7.31 ± 2.25 mm, P = 0.155) and was also larger in patients with CAS in both men and women (Fig. 1a). Even after adjusting for age, diabetes, hypertension, and BMI, EAT thickness was larger in patients with CAS than in patients without CAS in all patients and in each sex (Table 2).

Age, diabetes, and EAT thickness were associated with CAS by univariate analysis in both sexes. Dyslipidemia was associated with CAS only in men, whereas hypertension was associated only in women by univariate analysis. Using multivariate analysis, EAT thickness was independently associated with CAS in both sexes (Table 3). However, the impact of EAT on the presence of CAS in men was greater than that in women by interaction analysis (Fig. 2).

Difference in the relationship between EAT thickness and CAS by menopausal status

The EAT thickness of postmenopausal women was larger than that of premenopausal women (7.59 ± 2.25 vs 5.80 ± 1.57 mm, P < 0.001). This trend remained after adjusting for age, diabetes, hypertension, and BMI (7.43 ± 0.12 mm, 95% CI 7.19–7.67 vs 6.68 ± 0.33 mm, 95% CI 6.04–7.32, P = 0.041). In postmenopausal women, EAT thickness, age, hypertension, and diabetes were related to CAS by univariate analysis (Table 4). EAT thickness was larger in postmenopausal women with CAS than those without CAS (Fig. 1b), and this trend persisted after adjusting for age, diabetes, hypertension, and BMI (Table 2). The multivariate analysis also showed that EAT thickness was independently associated with CAS in postmenopausal women (OR 1.244, 95% CI 1.09–1.41, P = 0.001).

However, in premenopausal women, there was no difference in EAT thickness between patients with and without CAS (Table 2), and EAT thickness was not related to CAS. Only a history of smoking was associated with CAS in premenopausal women (Table 4). In comparison to age-matched men (mean age = 47.5 ± 5.9 years old), EAT thickness was larger in men than in premenopausal women (6.73 ± 2.11 mm vs 5.80 ± 1.57 mm, P = 0.008). In these men, EAT thickness was larger in patients with CAS than patients without CAS.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were as follows: (1) EAT thickness was similar between men and women and was closely related with the presence of CAS in both sexes, but a stronger relationship was shown in men. (2) When analyzed by menopausal status in women, EAT thickness was one of the independent parameters relating to the presence of CAS in postmenopausal women but not in premenopausal women.

Based on previous studies, it was generally accepted that EAT has a direct role in the development and progression of coronary atherosclerosis [1, 3]. We also demonstrated that EAT thickness has a significant association with CAS, as well as severity [16]. An increased amount of EAT would influence the structure and function of the coronary artery by altering the balance of secreting cytokines towards pro-atherogenic and pro-inflammatory conditions via the paracrine and vasocrine routes [18, 19]. In previous studies, a significant relationship between EAT amount and coronary artery calcification was shown in men but not in women [20,21,22]. By contrast, this sex difference in relation to EAT with coronary artery calcification was not demonstrated in large cohort studies [23, 24]. Dagvasumberel et al. also reported that an increased EAT volume was associated with CAS (luminal narrowing over 50%) in men only [25]. However, in this study, EAT thickness was independently associated with CAS in women, as well as in men. According to menopausal status, EAT was associated with CAS only in postmenopausal women. Therefore, an independent relationship of EAT with CAS in all women may be reflected by the result in postmenopausal women, as the majority of women were of postmenopausal status (84%).

The reasons for the difference are unclear, but a possible cause is the difference of sexual dimorphism in EAT during aging. Experimental data revealed that EAT function decreased with aging in female rats but was relatively unchanged with age in male rats [26, 27]. These differences might help us to understand the sex differences of the relationship of EAT and CAS and change of these associations after menopause in women. Another possible cause is sex hormonal status. Estrogen affects body fat composition and energy expenditure. Through menopausal transition, women undergo an increase in visceral adipose tissue and a decrease in energy expenditure [28, 29]. Both subcutaneous adipose tissue and visceral adipose tissue express estrogen receptor (ER)α and ERβ. ERα plays an important role in the activity of adipocytes and sexual dimorphism of fat distribution. However, the effects of estradiol (E2) on lipolysis and lipid accumulation are different in specific regions of the body [29]. E2 inhibits lipolysis in subcutaneous adipocytes by increasing the expression of α2A-adrenergic receptors via ERα [30, 31], but this effect was much smaller in visceral adipocytes [32]. Therefore, lower levels of estrogen might lead to increased amounts of visceral adipose tissue, including EAT, in men and postmenopausal women. In addition, EAT is regarded as white adipose tissue, but recent studies reported that EAT has characteristics of brown or beige adipose tissue. Sacks et al. demonstrated that EAT has high expression of mitochondrial uncoupling protein-1 (UCP-1), which is the main marker of brown adipose tissue [33]. Estrogen could increase the gene expression of UCP-1 [34] and influence mitochondriogenesis via the mitochondrial ERα of brown adipose tissue [35]. Therefore, the feature of EAT as brown adipose tissue, which was associated with a more favorable effect on cardiovascular disease [36, 37], might be relatively small in men and diminish in postmenopausal women. Finally, as estrogen is associated with decreased expression of pro-inflammatory adipokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukins [29], postmenopausal women tend to change to inflammatory conditions. Therefore, it is inferred that the decrement of estrogen might be one of the possible cause of increasing EAT thickness, which is related to CAS in postmenopausal women.

In this study, EAT thickness was more relevant to CAS in men than in women even with a similar EAT thickness between men and women. The presence of CAS was also lower in women than in men, which was consistent with other previous studies [16, 38]. It is known that ischemia but no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) is more prevalent in women, and they often have coronary microvascular dysfunction [39, 40]. Therefore, a considerable number of women with INOCA should be classified as no CAS, and the power of EAT thickness might be attenuated.

The present study has several limitations. As this study was cross-sectional, it was impossible to demonstrate a cause-effect relationship between EAT and CAS. We did not measure serum markers such as adipokines and inflammation markers, except hs-CRP. In this study, hs-CRP was not statistically different between men and women, but postmenopausal women had higher hs-CRP than premenopausal women. Another limitation was that menopausal status had been assessed by self-questionnaire. The measurement of E2 levels had not been performed, and the direct relation between estrogen and EAT had not been conducted. Finally, EAT amount was assessed by the thickness on echocardiography. Even though EAT thickness measured by echocardiography correlated with EAT volume by computed tomography [41], it might be less accurate. However, echocardiography has the virtue of lower cost and no radiation exposure compared to the other measurement techniques, and it could also be easily performed at bedside.

Conclusion

An increase in EAT thickness was independently related to the presence of CAS in both men and women, with it being stronger in men. According to menopausal status in women, EAT thickness is significantly associated with CAS only in postmenopausal women. From these results, we could show the different relationships of EAT to CAS between men and women, and the assessment of EAT thickness would be helpful to estimate the risk of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease in patients with suspected angina.

References

Patel VB, Shah S, Verma S, Oudit GY. Epicardial adipose tissue as a metabolic transducer: role in heart failure and coronary artery disease. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22:889–902.

Pierdomenico SD, Pierdomenico AM, Cuccurullo F, Iacobellis G. Meta-analysis of the relation of echocardiographic epicardial adipose tissue thickness and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:73–8.

Mancio J, Azevedo D, Saraiva F, Azevedo AI, Pires-Morais G, Leite-Moreira A, Falcao-Pires I, Lunet N, Bettencourt N. Epicardial adipose tissue volume assessed by computed tomography and coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;19(5):490–7.

Nakanishi K, Fukuda S, Tanaka A, Otsuka K, Taguchi H, Shimada K. Relationships between periventricular epicardial adipose tissue accumulation, coronary microcirculation, and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33:1489–97.

Karastergiou K, Smith SR, Greenberg AS, Fried SK. Sex differences in human adipose tissues – the biology of pear shape. Biol Sex Differ. 2012;3:13.

Bloor ID, Symonds ME. Sexual dimorphism in white and brown adipose tissue with obesity and inflammation. Horm Behav. 2014;66:95–103.

Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. The sexual dimorphism of obesity. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;402:113–9.

Abdulnour J, Doucet E, Brochu M, Lavoie JM, Strychar I, Rabasa-Lhoret R, Prud’homme D. The effect of the menopausal transition on body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors: a Montreal-Ottawa New Emerging Team group study. Menopause. 2012;19:760–7.

van der Leeuw J, Wassink AM, van der Graaf Y, Westerveld HE, Visseren FL. Age-related differences in abdominal fat distribution in premenopausal and postmenopausal women with cardiovascular disease. Menopause. 2013;20:409–17.

El Khoudary SR, Shields KJ, Janssen I, Hanley C, Budoff MJ, Barinas-Mitchell E, Everson-Rose SA, Powell LH, Matthews KA. Cardiovascular fat, menopause, and sex hormones in women: the SWAN Cardiovascular Fat Ancillary Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:3304–12.

Kim SA, Kim MN, Shim WJ, Park SM. Epicardial adipose tissue is related to cardiac function in elderly women, but not in men. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27:41–7.

Cho KI, Shim WJ, Park SM, Kim MA, Kim HL, Son JW, Hong KS. Association of depression with coronary artery disease and QTc interval prolongation in women with chest pain: data from the KoRean wOmen’S chest pain rEgistry (KoROSE) study. Physiol Behav. 2015;143:45–50.

Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation 2002, 106:3143–3421.

Iacobellis G, Willens HJ. Echocardiographic epicardial fat: a review of research and clinical applications. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:1311–9 quiz 1417-1318.

Graeff DB, Foppa M, Pires JC, Vigo A, Schmidt MI, Lotufo PA, Mill JG, Duncan BB. Epicardial fat thickness: distribution and association with diabetes mellitus, hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in the ELSA-Brasil study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:563–72.

Kim MN, Kim HL, Park SM, Shin MS, Yu CW, Kim MA, Hong KS, Shim WJ. Association of epicardial adipose tissue with coronary spasm and coronary atherosclerosis in patients with chest pain: analysis of data collated by the KoRean wOmen’S chest pain rEgistry (koROSE). Heart Vessel. 2018;33:17–24.

Shi KL, Qi L, Mao DB, Chen Y, Qian JY, Sun YB, Guo XG. Impact of age on epicardial and pericoronary adipose tissue volume. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:3257–65.

Iacobellis G. Local and systemic effects of the multifaceted epicardial adipose tissue depot. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:363–71.

Chistiakov DA, Grechko AV, Myasoedova VA, Melnichenko AA, Orekhov AN. Impact of the cardiovascular system-associated adipose tissue on atherosclerotic pathology. Atherosclerosis. 2017;263:361–8.

Bos D, Shahzad R, van Walsum T, van Vliet LJ, Franco OH, Hofman A, Niessen WJ, Vernooij MW, van der Lugt A. Epicardial fat volume is related to atherosclerotic calcification in multiple vessel beds. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:1264–9.

Mancio J, Pinheiro M, Ferreira W, Carvalho M, Barros A, Ferreira N, Vouga L, Ribeiro VG, Leite-Moreira A, Falcao-Pires I, Bettencourt N. Gender differences in the association of epicardial adipose tissue and coronary artery calcification: EPICHEART study: EAT and coronary calcification by gender. Int J Cardiol. 2017;249:419–25.

Bettencourt N, Toschke AM, Leite D, Rocha J, Carvalho M, Sampaio F, Xara S, Leite-Moreira A, Nagel E, Gama V. Epicardial adipose tissue is an independent predictor of coronary atherosclerotic burden. Int J Cardiol. 2012;158:26–32.

Rosito GA, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Ruberg FL, Mahabadi AA, Vasan RS, O’Donnell CJ, Fox CS. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:605–13.

McClain J, Hsu F, Brown E, Burke G, Carr J, Harris T, Kritchevsky S, Szklo M, Tracy R, Ding J. Pericardial adipose tissue and coronary artery calcification in the Multi-ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:1056–63.

Dagvasumberel M, Shimabukuro M, Nishiuchi T, Ueno J, Takao S, Fukuda D, Hirata Y, Kurobe H, Soeki T, Iwase T, et al. Gender disparities in the association between epicardial adipose tissue volume and coronary atherosclerosis: a 3-dimensional cardiac computed tomography imaging study in Japanese subjects. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2012;11:106.

Kocher C, Christiansen M, Martin S, Adams C, Wehner P, Gress T, Santanam N. Sexual dimorphism in obesity-related genes in the epicardial fat during aging. J Physiol Biochem. 2017;73:215–24.

Fei J, Cook C, Blough E, Santanam N. Age and sex mediated changes in epicardial fat adipokines. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:488–94.

Lovejoy JC, Champagne CM, de Jonge L, Xie H, Smith SR. Increased visceral fat and decreased energy expenditure during the menopausal transition. Int J Obes. 2008;32:949–58.

Lizcano F, Guzman G. Estrogen deficiency and the origin of obesity during menopause. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:757461.

Pedersen SB, Kristensen K, Hermann PA, Katzenellenbogen JA, Richelsen B. Estrogen controls lipolysis by up-regulating alpha2A-adrenergic receptors directly in human adipose tissue through the estrogen receptor alpha. Implications for the female fat distribution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1869–78.

Monjo M, Pujol E, Roca P. alpha2- to beta3-adrenoceptor switch in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and adipocytes: modulation by testosterone, 17beta-estradiol, and progesterone. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E145–50.

Gormsen LC, Host C, Hjerrild BE, Pedersen SB, Nielsen S, Christiansen JS, Gravholt CH. Estradiol acutely inhibits whole body lipid oxidation and attenuates lipolysis in subcutaneous adipose tissue: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in postmenopausal women. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167:543–51.

Sacks HS, Fain JN, Bahouth SW, Ojha S, Frontini A, Budge H, Cinti S, Symonds ME. Adult epicardial fat exhibits beige features. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1448–55.

Pedersen SB, Bruun JM, Kristensen K, Richelsen B. Regulation of UCP1, UCP2, and UCP3 mRNA expression in brown adipose tissue, white adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle in rats by estrogen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:191–7.

Velickovic K, Cvoro A, Srdic B, Stokic E, Markelic M, Golic I, Otasevic V, Stancic A, Jankovic A, Vucetic M, et al. Expression and subcellular localization of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in human fetal brown adipose tissue. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:151–9.

Franssens BT, Hoogduin H, Leiner T, van der Graaf Y, Visseren FLJ. Relation between brown adipose tissue and measures of obesity and metabolic dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;46:497–504.

Nam HY, Jun S. Association between active brown adipose tissue and coronary artery calcification in healthy men. Nuklearmedizin. 2017;56:184–90.

Kim HL, Kim MA, Shim WJ, Oh S, Kim M, Park SM, Kim YH, Na JO, Shin MS, Yoon HJ, et al. Sex difference in the association between brachial pulse pressure and coronary artery disease: the Korean Women’s Chest Pain Registry (KoROSE). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19:38–44.

Bairey Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Walsh MN, Fleg JL. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA): developing evidence-based therapies and research agenda for the next decade. Circulation. 2017;135:1075–92.

Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, Brennan JM, Redberg RF, Anderson HV, Brindis RG, Douglas PS. Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:886–95.

Hirata Y, Yamada H, Kusunose K, Iwase T, Nishio S, Hayashi S, Bando M, Amano R, Yamaguchi K, Soeki T, et al. Clinical utility of measuring epicardial adipose tissue thickness with echocardiography using a high-frequency linear probe in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1240–1246.e1241.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Korean Women’s Chest Pain Multicenter Registry, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data and are not publicly available. However, data are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Women’s Heart Disease Research Working Group in Korea.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MNK contributed to the conception or design and to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. SMP contributed to the conception or design and to the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; critically revised the manuscript, and gave final approval. DHC, HLK, MSS, MAK, and KSH made substantial contributions to the acquisition of data. WJS made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. And all authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Korean Women’s Chest Pain Multicenter Registry (koROSE) was approved by the Institutional Review Board in each institution which participates in this registry. It is mandatory to obtain an informed written consent for patient registration in all participant institutions; all enrolled patients agreed to this registry. All patients who were enrolled in the registry had agreed to provide their information about clinical characteristics and test results like ECG, treadmill, echocardiography, and coronary status. Therefore, the additional consent for this analysis was not required. And we used the data from four centers (approximately 65% of total registered patients) where the measurement of the EAT thickness was available.

IRB number:

2012AN0011 Korea University Medical center, Anam Hospital, Korea.

06-2011-222 Seoul National University Boramae Hospital, Korea.

GIRBA2642 Gacheon University Kil Hospital, Korea.

2012-6 Hallym University College of Medicine, Korea.

Consent for publication

None

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, MN., Park, SM., Cho, DH. et al. The relationship between epicardial adipose tissue and coronary artery stenosis by sex and menopausal status in patients with suspected angina. Biol Sex Differ 9, 52 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-018-0212-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-018-0212-8