Abstract

Background

Gut dysbiosis is observed in several neuropsychiatric disorders exhibiting increases in anxiety behavior, and recent work suggests links between gut inflammation and such disorders. One source of this inflammation may be lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a toxic component of gram-negative bacteria. Here, we (1) determine whether oral gavage of LPS, as a model of gut-derived endotoxemia, affects anxiety-like and/or repetitive behaviors; (2) test whether these changes depend on TLR4 signaling; and (3) test the extent to which gut-derived endotoxin and TLR4 antagonism affects males and females differently.

Methods

In experiment 1, male wild-type (WT) and Tlr4−/− mice were tested for locomotor, anxiety-like, and repetitive behaviors in an automated open field test apparatus, 2 h after oral gavage of LPS or saline. In experiment 2, male and female WT mice received an oral gavage of LPS and an injection of one or two TLR4 antagonists that target different TLR4 signaling pathways ((+)-naloxone and LPS derived from R. sphaeroides (LPS-RS)). Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify effects of treatment, sex, and genotype and their interaction.

Results

In experiment 1, oral gavage of LPS increased anxiety-like behavior in male WT mice but not in Tlr4−/− mice. In experiment 2, oral gavage of LPS increased anxiety-like and decreased repetitive behaviors in WT mice of both sexes. Neither antagonist directly blocked the effects of orally administered LPS. However, treatment with (+)-naloxone, which blocks the TRIF pathway of TLR4, had opposing behavioral effects in males and females (independent of LPS treatment). We also identified sex differences in the expression of interleukin-6, a pro-inflammatory cytokine, in the gut both in basal conditions and in response to LPS.

Conclusion

In spite of the ubiquitous nature of LPS in the gut lumen, this is the first study to demonstrate that intestinally derived LPS can initiate behavioral aspects of the sickness response. While an increased enteric load of LPS increases anxiety-like behavior in both sexes, it likely does so via sex-specific mechanisms. Similarly, TLR4 signaling may promote baseline expression of repetitive behavior differently in males and females. This study lays the groundwork for future interrogations into connections between gut-derived endotoxin and behavioral pathology in males and females.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, defined as a shift toward pathological, pro-inflammatory microbial species, has been linked to a number of neuropsychiatric disorders associated with increased expression of anxiety behavior, including autism [1,2,3], ADHD [4], and psychological pathologies comorbid with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [5, 6]. Microbiota-induced gut inflammation may mediate these behavioral pathologies. An important agent in these effects is likely to be lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a pathogenic component of gram-negative bacteria, which is endogenous to the gut microbiota [7]. When injected systemically, LPS produces well-documented behavioral alterations collectively called “sickness behavior,” which includes an increase in anxiety-like behaviors [8, 9] and suppression of compulsive and repetitive behaviors [10,11,12].

Intraperitoneal injections of LPS allow direct exposure of LPS to extra-intestinal peritoneal leukocytes that produce systemic cytokines that will provoke a sickness response. Likewise, intravenous injections of LPS facilitate its fast and robust interaction with splenic immune cells and circulating leukocytes. However, it is unknown whether elevations of serum LPS levels originating from gut barrier dysfunction, observed in rodent models of gut dysbiosis (such as emulsifier-fed mice [13], mice with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis [14, 15], high-fat diet-fed mice [16], and toll-like receptor 2 knockout (Tlr2−/−) mice [17]), are responsible for increases in anxiety-like behavior observed in these models. These studies reliably demonstrate a 2- to 3-fold increase in serum LPS levels in experimental subjects relative to controls, a condition termed “metabolic endotoxemia” [18]. As even a 10-μg/kg dose of LPS (10 times lower than in most published studies) is sufficient to increase serum levels of LPS to 25× above baseline [19], it is questionable whether intraperitoneal injections recapitulate the dynamics of LPS-induced inflammation observed in “metabolic endotoxemia.” Furthermore, the site of action may make a difference, as an inflammatory stimulus injected intraperitoneally may differ in its neurobehavioral effects from an inflammatory stimulus administered orally.

Under most circumstances, LPS present on gut bacteria does not cause pathology. However, increased intestinal loads of LPS may breach the intestinal lining, activate intestinally associated innate immune cells, and produce metabolic endotoxemia [18]. Elevated gut levels of gram-negative bacteria have been reported in clinical populations, such as children with autism or individuals with celiac disease [20, 21]. Furthermore, the severity of gastrointestinal conditions correlates positively with levels of anxiety behavior in autistic children [22,23,24,25]. In addition, elevated fecal levels of LPS are reported for rodent models of diseases such as diet- and emulsifier-induced obesity, as well as colitis; microbiota transfer from each of these disease models into control subjects causes similar immune and/or behavioral deficits to those observed in the respective disease model [16, 26,27,28]. However, whether gut-derived LPS influences anxiety behavior remains untested.

The purpose of this study is to (1) determine whether oral gavage of LPS, as a model of gut dysbiosis, affects anxiety-like and/or repetitive behaviors; (2) test whether these changes depend on TLR4 signaling; and (3) test the extent to which gut-derived endotoxin and TLR4 antagonism affects males and females differently. Here, we show that LPS triggers behavioral changes in males as well as females, but the underlying signaling mechanisms may differ. Furthermore, the effects of gut-derived LPS may not depend on systemic TLR4 signaling.

Methods

Animals

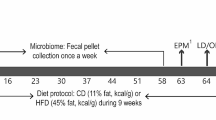

Three-month old C57Bl/6J mice were used to test the effects of gut-derived LPS on anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors. For experiment 1, 14 male wild-type (C57Bl/6J) mice and 8 male Tlr4−/− (Tlr4lps-del on C57Bl/6 background) mice were randomly selected from a colony bred in-house. Founder mice for this colony were sourced from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). As this colony contained a negligible number of females, female subjects were not used in this experiment. For experiment 2, 64 male and 64 female C57Bl/6J mice were purchased at 10 weeks of age (Jackson Labs) and housed in our facility for 2 weeks prior to the study. For both experiments, all subjects were housed in same-sex pairs prior to the beginning of the study. The mice were housed in a room maintained in a 12:12 light-dark cycle, at 68–72 °F and approximately 50% humidity, and were fed ProLab 5001 diet ad libitum (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO). All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Georgia State University and were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All procedures were designed to minimize subject discomfort and use the fewest animals necessary for statistical analysis.

Experiment 1

On the day of testing, mice were single-housed and fasted for 2 h to ensure gastric emptying [29] and were then administered 300 μg/kg LPS in a total volume of 200 μl saline (LPS from Escherichia coli [O111:B4]; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or saline alone by oral gavage (7 per treatment group for WT mice and 4 per treatment group for Tlr4−/− mice). The tip of the gavage needle was dipped in a 30% sucrose solution to decrease gavage-related stress response [30]. Two hours after gavage treatment, subjects were transferred to an automated open field apparatus for 10 min to measure locomotor parameters (ambulatory episodes, ambulatory counts, ambulatory time, ambulatory distance, resting time, and average velocity), anxiety-like behaviors (time spent in the center zone, zone entries, number of rears, and time spent rearing), and repetitive behaviors (time spent in stereotypic circling, number of stereotypic counts, jump counts, jump time, number of clockwise reversals, and number of counterclockwise reversals). After behavior testing, serum samples were collected by terminal cardiac puncture blood collection under isoflurane anesthesia.

Experiment 2

To determine which TLR4 signaling cascade is responsible for the anxiogenic effects of orally administered LPS, we used (+)-naloxone (NIDA Drug Supply), which blocks the TLR4/TRIF cascade and has low affinity for mu-opioid receptors (1/1000 to 1/10000 the affinity of (−)-naloxone for mu-opioid receptors) [31, 32], and LPS-RS Ultrapure (InVivoGen, San Diego, CA; LPS derived from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, hereafter simply referred to as LPS-RS), which blocks the TLR4/MyD88 cascade [33]. LPS molecules, sourced from different bacterial species and strains, differ in level of immunogenicity, ranging from TLR4 agonists, such as E. coli-derived LPS, that produce robust inflammation to TLR4 antagonists, such as LPS derived from R. sphaeroides (LPS-RS), that block the inflammatory effects of pro-inflammatory LPS species [34, 35]. We selected a dose of 60 mg/kg of (+)-naloxone, administered 30 min prior to LPS challenge, as applying this dose and timing blocks sedation and motor impairments induced by acute exposure to ethanol, a condition associated with increased intestinal permeability [36, 37]. We selected a dose of 800 μg/kg of LPS-RS, injected 30 min prior to oral gavage of LPS, as intrathecal injection of this dose and timing has been demonstrated to block neuropathic pain induced by LPS [38].

To ensure gastric emptying, male and female mice were single-housed and fasted for 2 h [29]. Ultimately, eight mice of each sex were assigned to each 2 (gavage treatment) × 2 ((+)-naloxone treatment) × 2 (LPS-RS treatment) group. Ninety minutes into the fast, mice received 60 mg/kg (+)-naloxone in 200 μl saline, 800 μg/kg LPS-RS in 200 μl saline, (+)-naloxone and LPS-RS together in 200 μl saline, or 200 μl saline by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Thirty minutes later, subjects received saline or 300 μg/kg LPS by oral gavage. As in experiment 1, the tip of the gavage needle was dipped in a 30% sucrose solution prior to insertion. Two hours after the oral gavage, mice were tested on an automated open field apparatus as described for Experiment 1. Directly after behavior testing, mice were euthanized for serum and intestinal tissue collection.

Serum LPS

Hemolysis-free serum was generated by centrifugation of blood using serum separator tubes (Becton Dickerson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Serum was stored at − 20 °C in silanized tubes. On the day of analysis, serum was diluted 1/40 in LPS-free saline and residual plasma proteins were degraded via a 10-min 70 °C incubation [17]. Serum LPS concentrations were determined using a kit based on a Limulus amebocyte extract (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) according to manufacturer’s instructions, with samples run in duplicate.

RT-qPCR for intestinal tissue

We examined the expression of pro-inflammatory (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines in the gut in response to oral LPS exposure. To do so, 1 in. of jejunum tissue was homogenized in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for RNA extraction. Reverse transcription was performed with a SuperScript IV First-Stand Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) in a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA) and real-time PCR was performed in the LightCycler 96 System (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as previously described (Castillo-Ruiz et al. 2017). Primers used targeted messenger RNA for IL-10, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as reference gene (all validated primers from Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA).

Luminex cytokine assay

BioRad (Hercules, CA) 4-plex mouse Luminex kits were used to measure serum cytokine levels. The cytokines assayed were TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10. Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and samples were run in duplicate.

Statistical analyses

Using SPSS (version 23), univariate (ANOVA) and multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were performed on the data obtained from the automated open field test apparatus. Following ANOVAs, planned contrasts were performed on individual outcome variables to identify directionality between group differences. Multivariate statistics are useful to detect relationships between outcome variables and identify syndromes of behavioral effects, particularly in outcomes with statistically non-significant univariate ANOVAs [39]. Like ANOVA, which tests whether mean differences between groups on a single dependent variable occur by chance, MANOVA tests whether mean differences for a combination of dependent variables occur by chance. Discriminant analysis ranks outcome variables by their contribution to group separation along the combination of all dependent behavioral variables used in the ANOVA analyses. The same group of behavioral measures was used in all discriminant analyses across experiments 1 and 2. Only behavioral measures that differentiate the discriminant functions are listed in the structure matrix. Discriminant functions were validated with both original group case classification tests and leave-one-out cross-validation tests, which gives a more unbiased estimate of the generalizability of the discriminant functions [40, 41].

Effect sizes for sex, genotype, and treatment effects were reported as sample means with 95% confidence intervals. In addition, using SPSS, partial eta squared (“partial η2”) were reported as effect size measurements of variance within the ANOVA and MANOVA tests. Estimation of population means and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for WT males across experiments 1 and 2 using random effects meta-analysis. All confidence interval estimates were calculated with Exploratory Software for Confidence Intervals or ESCI [42, 43].

Two-way ANOVAs (sex by treatment) were performed for the analysis of gut cytokine expression using GraphPad Prism version 6.01. Significant effects were followed by Fisher’s LSD tests.

Results

Experiment 1: role of TLR4 in behavioral response to oral gavage of LPS

In line with other models of metabolic endotoxemia [17, 18], oral gavage of LPS in male WT mice increased serum levels of LPS 1.5-fold, 2 h after gavage treatment, t(8) = 16.96, p < 0.05 (one-tailed), n = 5/group, η2 = 0.34 [17, 18] (Fig. 1).

2 × 2 (genotype × gavage treatment) univariate ANOVAs across all behavioral measures showed that oral gavage of LPS significantly increased anxiety-like behavior in WT mice but not Tlr4−/− mice (n = 7/group for WT mice and n = 4/group for Tlr4−/− mice). In comparison to vehicle treatment, LPS decreased time spent in the center for WT mice, p < 0.01 but not for Tlr4−/− mice (genotype × gavage treatment interaction F(1,18) = 14.051, p < 0.01). If anything, LPS tended to increase time spent in the center for Tlr4−/− mice, although this did not reach significance (p = 0.107, Fig. 2a). When collapsing across gavage treatment, WT mice had a higher jump time (p < 0.001, Fig. 2e), whereas Tlr4−/− mice had a higher average velocity (p < 0.01, Fig. 2b), spent more time in stereotypic circling (p < 0.001, Fig. 2c), and had a higher number of stereotypic counts (p < 0.001, Fig. 2d). Additional file 1: Table S1 lists ANOVA statistics for all measures across main effects and interactions, including locomotor parameters (ambulatory episodes, ambulatory counts, ambulatory time, ambulatory distance, resting time, and average velocity), anxiety-like behaviors (time spent in the center zone, zone entries, number of rears, and time spent rearing), and repetitive behaviors (time spent in stereotypic circling, number of stereotypic counts, jump counts, jump time, number of clockwise reversals, and number of counterclockwise reversals).

Effects of oral gavage of LPS on male WT and Tlr4−/− mice. Experiment 1: effects of oral gavage of LPS on open field test behavioral outcomes in male WT and Tlr4−/− mice. a LPS significantly decreased time in the center zone for male WT mice, but there was a slight trend toward increased time spent in the center zone for male Tlr4−/− mice. b Male Tlr4−/− mice had significantly increased average velocity, c time spent in stereotypic circling, and d number of stereotypic counts compared with male WT mice. e However, male WT mice had a significantly higher jump time compared to male Tlr4−/− mice. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05; #p = 0.107

A 2 × 2 (genotype × gavage treatment) multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed on all behavioral measures, wherein all main effects and interactions were non-significant (not reported). The observed power for the main effect of gavage treatment (power = 20.9%), the main effect of genotype (power = 46.1%), and the gavage treatment by genotype interaction effect (power = 43.2%) were all under the nominal 80% level. This suggests that this experimental cohort may have been underpowered for a factorial MANOVA.

Although MANOVA did not reveal significant effects of genotype or gavage treatment, discriminant analysis revealed the contribution of behavioral outcome variables to group separation by genotype and gavage treatment. When subjects were designated to four groups based on genotype and gavage treatment, discriminant analysis revealed three discriminant functions that maximize group separation based on genotype, gavage treatment, or the interaction between these two factors. Function 1 explains 60.0% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.975; function 2 explains 35.6% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.959; and function 3 explains 4.4% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.765. Collectively, these discriminant functions significantly differentiated the treatment groups, Λ = 0.006, Χ2(42) = 77.077, p < 0.001. The structure matrix in Table 1 reveals the correlations between outcome variables and the discriminant functions. In the discriminant function plot (Fig. 3), function 1 demonstrates the opposing effects of gavage treatment on behavioral outcomes via the two genotypes, and the structure matrix shows this is predominantly driven by time spent in center zone (r = − 0.154), jump time (r = − 0.138), and jump counts (r = − 0.070) (Table 1). Function 2 separates groups by genotype, and this is driven predominantly by time spent in stereotypic circling (r = − 0.458), number of stereotypic counts (r = − 0.454), and time spent in the center zone (r = − 0.279) (Table 1). This suggests that while the genotypes are best distinguished on the basis of repetitive behaviors, gavage treatment affects anxiety-like and repetitive behavior differently in male WT and Tlr4−/− mice. Additional file 2: Table S2 demonstrates the results of a classification test to verify the validity of the discriminant functions plotted in Fig. 3. Using the original discriminant functions, 100% of the original grouped cases are correctly classified. These functions were further validated by a leave-one-out cross-validation procedure. Discriminant functions were re-computed with all subjects excluding one, and this procedure was repeated for all subjects. Across all analyses, 63.6% of cross-validated group cases were correctly classified, 38.6% above chance.

Canonical discriminant function plot for experiment 1. Experiment 1 discriminant function plot. Correlations between outcome variables and discriminant functions are listed in Table 1. Function 1 demonstrates an interaction between gavage treatment and genotype, mostly based on the differential effect of LPS on time spent in the center zone, time spent jumping, and jump counts in Tlr4−/− and WT mice, whereas function 2 separates groups based on genotype, largely driven by differences in number of stereotypic counts, time spent in stereotypic circling, and time spent in the center zone. Group centroids indicate the mean discriminant function value of each of the designated groups

Experiment 2: sex differences in TLR4 agonism and antagonism on anxiety-like and repetitive behavior

In this experiment, we observed that oral gavage of LPS significantly increased anxiety behavior in both males and females, but a specific TLR4 antagonist, (+)-naloxone, had opposing effects on anxiety and repetitive behavior in males and females. Full factorial 2 (sex) × 2 (gavage treatment: LPS or saline) × 2 (i.p. injection: LPS-RS or saline) × 2 (i.p. injection: (+)-naloxone or saline) MANOVA was performed on the same dependent variables analyzed in experiment 1 (n = 8/group). There were significant main effects of sex (F(16,96) = 9.751, p < 0.001) and gavage treatment (F(16,96) = 2.111, p < 0.05), and a sex by (+)-naloxone interaction effect (F(16,96) = 2.176, p < 0.05). All remaining main effects and interactions, including effects of LPS-RS treatment, were non-significant (not reported). ANOVAs revealed these main effects and interactions across a number of behavioral parameters (Additional file 3: Table S3), of which subsequent planned contrasts indicated directionality.

These planned contrasts revealed that LPS suppressed repetitive and increased anxiety-like behaviors in males and females. Since no significant sex by LPS treatment effects were found in any of the ANOVAs or MANOVA, males and females were grouped together for subsequent analyses. LPS treatment decreased number of zone entries, p < 0.05 (Fig. 4a), and increased number of rears, p < 0.05 (Fig. 4b). Across both sexes, LPS treatment decreased time spent in stereotypic circling, p = 0.05 (Fig. 4c), stereotypic counts, p < 0.05 (Fig. 4d), and jump counts, p < 0.05 (Fig. 4e).

Effects of oral gavage of LPS on male and female WT mice. Experiment 2: effects of intraperitoneal injection of TLR4 antagonists and oral gavage of LPS on open field test behavioral outcomes in male and female WT mice. Data presented as sex by gavage treatment. LPS significantly a decreased zone entries and b increased the number of rears in males and females relative to saline-treated subjects. Furthermore, LPS significantly decreased the number of c time spent in stereotypic circling, d stereotypic counts, and e jump counts relative to saline-treated subjects. In addition, females had a higher jump count than males. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05; (*) significant main effect of sex, p < 0.05

When planned contrasts were run for the effects of (+)-naloxone in each sex separately, time spent in stereotypic circling (Fig. 5a), stereotypic counts (Fig. 5b) and jump counts (Fig. 5d) were significantly affected in females (p < 0.05, in each case) but not in males (p > 0.1, in each case).

Effects of TLR4 antagonist (+)-naloxone treatment on male and female WT mice. Experiment 2: effects of intraperitoneal injection of TLR4 antagonists and oral gavage of LPS on open field test behavioral outcomes in male and female WT mice. Data presented as sex by (+)-naloxone treatment. a Overall, males spent significantly more time in stereotypic circling than females; however, (+)-naloxone significantly increased time in stereotypic circling in female mice. b In addition, (+)-naloxone significantly increased the number of stereotypic counts in female mice. For jumping behavior, (c) females jumped more than males, and d (+)-naloxone significantly increased jump counts in females. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05

Discriminant analysis confirms that LPS increased anxiety behavior similarly in males and females, while (+)-naloxone had different effects in males and females. As for gavage treatment, discriminant analysis revealed three discriminant functions on data from subjects grouped by sex and gavage treatment. Function 1 explains 80.6% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.758; function 2 explains 13.8% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.433; and function 3 explains 5.6% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.292. Collectively, these discriminant functions significantly differentiated the treatment groups, Λ = 0.317, Χ2(45) = 133.937, p < 0.001. The discriminant function plot (Fig. 6) shows that function 1 separates groups based on sex, and the structure matrix (Table 2) reveals this is predominantly driven by sex differences in jump counts (r = − 0.616), jump time (r = − 0.508), and ambulatory time (r = − 0.392). Function 2 separates groups based on gavage treatment, and LPS appears to affect males and females in a similar fashion along outcome variables, predominantly number of rears (r = 0.453), zone entries (r = − 0.429), and stereotypic counts (r = − 0.400). Additional file 4: Table S4 displays results of the original grouping and leave-one-out classification tests. 64.6% of original grouped cases were correctly classified, and 45.7% of cross-validated grouped cases were correctly classified, 20.7% above chance. (The same group of behavioral measures used in experiment 1 was also used in discriminant analyses performed for experiment 2. Only behavioral measures that differentiate the discriminant functions are listed in the structure matrix.)

Canonical discriminant function plot for experiment 2 (sex × gavage treatment). Experiment 2 discriminant function plot (sex by gavage treatment). Correlations between outcome variables and discriminant functions are listed in Table 2. Function 1 separates groups based on sex, largely driven by differences in time spent jumping, jump time, and ambulatory time, whereas function 2 separates groups by gavage treatment, mostly driven by number of rears, zone entries, and stereotypic counts. LPS affects males and females in a similar fashion across discriminant function 2. Group centroids indicate the mean discriminant function value of each of the designated groups

Discriminant analysis also indicates that (+)-naloxone affected repetitive and locomotor behaviors differently in males and females, revealing three discriminant functions (Fig. 7, Table 3). Rear count is automatically excluded from the discriminant analysis, based on its lack of contribution to the discriminant functions. Function 1 explains 81.5% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.764, Function 2 explains 11.8% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.410, and function 3 explains 6.7% of the variance, canonical R2 = 0.322. Collectively, these discriminant functions significantly differentiated the treatment groups, Λ = 0.311, Χ2(45) = 136.022, p < 0.001. As shown in the discriminant analysis where subjects are grouped by sex and gavage treatment, the discriminant function plot shows that function 1 separates groups based on sex and the structure matrix reveals this is predominantly driven by sex differences in jump counts (r = − 0.623), jump time (r = − 0.496), and ambulatory time (r = − 0.416). Function 2 separates groups based on (+)-naloxone treatment, and (+)-naloxone appears to affect males and females differently along outcome variables, predominantly stereotypic counts (r = 0.545), ambulatory episodes (r = 0.526), and time spent in stereotypic circling (r = 0.523). Additional file 5: Table S5 displays results of the original grouping and leave-one-out classification tests. 65.4% of original grouped cases were correctly classified, and 48.0% of cross-validated grouped cases were correctly classified, 23.0% above chance.

Canonical discriminant function plot for experiment 2 (sex × (+)-naloxone treatment). Experiment 2 discriminant function plot (sex by (+)-naloxone treatment). Correlations between outcome variables and discriminant functions are listed in Table 3. Function 1 separates groups based on sex, largely driven by differences in time spent jumping, jump time, and ambulatory time, whereas function 2 demonstrates an interaction between sex and (+)-naloxone treatment, mostly based on the sexually differential effect of (+)-naloxone on stereotypic counts, ambulatory episodes, and time spent in stereotypic circling. Group centroids indicate the mean discriminant function value of each of the designated groups

Since neither TLR4 antagonist blocked the specific effects of LPS, we sought to identify the systemic and intestinal inflammatory effects of the oral LPS treatment in WT mice not treated with TLR4 antagonists. Gavage treatment resulted in non-significant elevation of serum endotoxin levels in male subjects in a meta-analysis across experiments 1 and 2 (p > 0.05) (Additional file 6: Figure S1), and there were no significant main effects of sex or gavage treatment, or interactions between sex and gavage treatment, on serum LPS levels in experiment 2 (data not shown). In addition, cytokine Luminex was performed on serum samples from experiment 2. There were no significant effects of gavage treatment on serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, or IL-10 (data not shown). However, oral gavage of LPS did modulate IL-6 expression levels in intestinal tissue in a sexually differentiated manner (sex-by-treatment interaction F(1,21) = 12.38, p = 0.002), increasing IL-6 expression in females (p = 0.04) while decreasing it in males (p = 0.009, Fig. 8a). IL-10, TNF-α, and IL-1β expression levels were not significantly altered by the oral LPS treatment (Fig. 8b–d).

Effects of oral gavage of LPS on gut cytokine expression in female and male mice. a Expression levels of IL-6 showed a sex-dependent effect, with LPS causing a reduction of IL-6 in males and an increase in females. b–d However, the expression of IL-10, TNF-α, and IL-1β did not depend on sex or experimental treatment. Data are expressed relative to levels of saline-treated males. Error bars are 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

Meta-analyses across experiments 1 and 2

A random effects meta-analysis was performed across experimental cohorts in order to obtain more general estimates of the effects of oral gavage of LPS on behavior. As both experiments used WT males, all WT males from experiment 1 and WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists in experiment 2 were used for the meta-analyses (total n = 15/group). Across experiments 1 and 2, there were significant effects of LPS on time spent in the center zone (p < 0.01), time spent in stereotypic circling (p < 0.01), and stereotypic counts (p < 0.01) (Fig. 9). There were non-significant effects of LPS on parameters of locomotion, including ambulatory counts (p > 0.1), ambulatory episodes (p > 0.10), ambulatory time (p > 0.1), ambulatory distance (p > 0.10), resting time (p > 0.10), and average velocity (p > 0.10). All other behavioral parameters were also non-significant (Additional file 7: Figure S2; Additional file 8: Figure S3; Additional file 9: Figure S4; Additional file 10: Figure S5; Additional file 11: Figure S6; Additional file 12: Figure S7; Additional file 13: Figure S8; Additional file 14: Figure S9; Additional file 15: Figure S10; Additional file 16: Figure S11; Additional file 17: Figure S12 and Additional file 18: Table S7).

Meta-analyses of behavior in WT males of experiments 1 and 2. Forest plots of meta-analyses of a time spent in center zone, b time spent in stereotypic circling, c stereotypic counts, and d ambulatory counts measured in experiment 1 (top green bar) and experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics

Discussion

Here, we observe that gut-derived LPS elicits various aspects of the canonical sickness behavior response, with the exception of lethargy. In our first experiment, LPS increased anxiety-like behavior in male WT mice whereas no such effect was found in male Tlr4−/− mice. In the second experiment, LPS similarly increased anxiety-like behaviors in WT males and females. Neither TLR4 antagonist ((+)-naloxone nor LPS-RS) blocked the effects of gavage treatment. However, (+)-naloxone, a TLR4/TRIF specific antagonist, which does not interact with opioid receptors [31, 32], affected behavior differently in males and females. Furthermore, LPS-RS did not significantly alter behavior, suggesting that the MyD88 pathway may not be involved in anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors generated by gut-derived endotoxin. With the presented data, we offer oral administration of LPS as a model of gut dysbiosis that may result from overgrowth of pathogenic gram-negative bacteria in gut microbiota.

While LPS increased anxiety behavior 2 h after treatment, it did not increase lethargy (indexed as hypolocomotion), as seen 2–6 h after systemic injections of LPS. Importantly, oral gavage of LPS induced similar increases in anxiety-like behavior to those observed after direct injection [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. This suggests that oral gavage of LPS specifically induced anxiety-like behavior without inducing a generalized sickness response.

In experiment 1, an oral gavage of LPS increased anxiety-like behaviors in male WT mice, as measured by decreased time spent in the center zone of the open field test. In experiment 2, the oral gavage of LPS did not strongly affect time spent in the center zone in subject mice. This may be a result of increased anxiety stemming from the additional manipulations (e.g., intraperitoneal injection) in this experiment as both gavage and injections can increase anxiety [30, 55] or from behavioral variability across experimental cohorts. Nevertheless, multivariate analyses from experiment 2 indicate that gut-derived LPS produced a syndrome of behavioral alterations that includes increases in anxiety-like behaviors (increased incidence of vertical stretch posture and decreased zone entries) and decreases in repetitive behaviors (decreased jump time and jump counts), albeit along a slightly different combination of measures from that found in experiment 1. In support of the conclusion from the multivariate analyses that LPS affects anxiety-like behaviors in both experiments, meta-analysis of LPS effects in WT males indicates that the observed reduction in time spent in the center zone, a highly used index of anxiety-like behavior [56, 57], is similar to the reported range of reduced time spent in the center zone for male mice injected intraperitoneally or intravenously with LPS (20 to 60 s difference per 5 min segment) [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Overall, these data demonstrate the utility of multivariate analyses to highlight similar behavioral effects across differing contexts.

Our data indicate that the behavioral effects of gut-derived LPS are mediated through TLR4. Oral administration of LPS significantly increased anxiety-like behavior in WT mice but not in Tlr4−/− mice. If anything, there was a trend toward LPS increasing time spent in the center zone in Tlr4−/− mice, suggesting that LPS may interact with other innate immune receptors to decrease anxiety. TLR4 antagonists, however, did not directly block the effects of LPS gavage on behavior. It is unlikely that this is due to ineffective dosage, as we chose dosages of antagonists based on the literature [36,37,38, 58], and (+)-naloxone affected behavior regardless of LPS treatment in this study. Measurement of cytokines suggests that LPS acted primarily at the level of the gut, as we did not find elevation of inflammatory markers in serum but did find a significant elevation of IL-6 expression in the gut. If so, it may be that the TLR4 antagonists did not intervene effectively at the site of action of the LPS. Orally administered LPS likely interacts with TLR4 present on the apical surface of intestinal epithelial cells. It is plausible that our antagonists, when injected intraperitoneally, do not have sufficient access to these receptors.

Our data suggest that there may be sex differences in constitutive TLR4 activity and its downstream effects on locomotor and repetitive behaviors. The antagonist (+)-naloxone, which blocks the TLR4/TRIF signaling pathway, increased stereotypic circling time and ambulatory episodes in females while decreasing these behaviors in males, regardless of gavage treatment. This suggests that the TLR4/TRIF pathway differently modulates these behaviors in males and females. This is in line with literature that shows (+)-naloxone more effectively blocks TLR4-modulated nociception in female than in male rats [59]. In our study, oral LPS treatment increased intestinal IL-6 expression in females and suppressed it in males. As IL-6 expression depends on the TLR4/TRIF pathway [60], it is possible that sex differences in this pathway contributed to sex differences in LPS effects on IL-6 observed in this study.

Our data also demonstrate that TLR4 activation may suppress repetitive behaviors. Genetic deletion of TLR4 in males and blockade of TLR4 signaling (with (+)-naloxone) in females both increase stereotypic circling. These effects may possibly be driven by the suppression of allergic-type (Th2-driven) immune profiles by TLR4, as Tlr4−/− mice are reported to show enhanced allergic responses [61, 62]. In line with this prediction, a number of studies demonstrate that allergic-type immune profiles increase repetitive behaviors [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. It is notable that the TLR4 antagonist (+)-naloxone decreased stereotypic circling in males, while enhancing it in females. There are documented sex differences in cytokine responses to TLR4 activation [59, 71]. Our data further suggest potential sex differences in the TLR4/TRIF pathway in males and females, and these differences may contribute to the sex difference we observed in stereotypic circling among saline-treated mice. Alignment of the effects of TLR4 genetic mutation in males and effects of (+)-naloxone in females, and contrary effects of (+)-naloxone in males, suggests that TLR4 may play the same role in males and females, but the underlying signaling pathways may differ between the sexes.

Conclusion

In spite of the ubiquitous nature of LPS in the gut lumen, this is the first study to demonstrate that gut-derived LPS can initiate behavioral aspects of the sickness response. Our results suggest that an increased intestinal load of LPS similarly increases anxiety-like behavior and suppresses repetitive behavior in males and females. However, to the extent this is mediated through TLR4 activation, this may occur via differing mechanisms. Furthermore, different actions of the TLR4/TRIF pathway may drive baseline differences in repetitive behaviors in males and females.

Abbreviations

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MANOVA:

-

Multivariate analysis of variance

- MyD88:

-

Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- TLR4:

-

Toll-like receptor 4

- TRIF:

-

TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-beta

- WT:

-

Wild-type

References

Finegold SM, Downes J, Summanen PH. Microbiology of regressive autism. Anaerobe. 2012;18(2):260–2.

Mayer EA, Knight R, Mazmanian SK, Cryan JF, Tillisch K. Gut microbes and the brain: paradigm shift in neuroscience. J Neurosci. 2014;34(46):15490–6.

Mayer EA, Padua D, Tillisch K. Altered brain-gut axis in autism: comorbidity or causative mechanisms? BioEssays. 2014;36(10):933–9.

Petra AI, Panagiotidou S, Hatziagelaki E, Stewart JM, Conti P, Theoharides TC. Gut-microbiota-brain axis and its effect on neuropsychiatric disorders with suspected immune dysregulation. Clin Ther. 2015;37(5):984–95.

Bannaga AS, Selinger CP. Inflammatory bowel disease and anxiety: links, risks, and challenges faced. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:111–7.

Ray A, Dittel BN. Interrelatedness between dysbiosis in the gut microbiota due to immunodeficiency and disease penetrance of colitis. Immunology. 2015;146(3):359–68.

Marshall JC. Lipopolysaccharide: an endotoxin or an exogenous hormone? Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 7):S470–80.

Dantzer R. Cytokine-induced sickness behavior: mechanisms and implications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;933:222–34.

Dantzer R. Cytokine, sickness behavior, and depression. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2009;29(2):247–64.

Liblau RS, Singer SM, McDevitt HO. Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cells in the pathogenesis of organ-specific autoimmune diseases. Immunol Today. 1995;16(1):34–8.

Gentile A, Fresegna D, Musella A, Sepman H, Bullitta S, De Vito F, Fantozzi R, Usiello A, Maccarrone M, Mercuri NB, Lutz B, Mandolesi G, Centonze D. Interaction between interleukin-1beta and type-1 cannabinoid receptor is involved in anxiety-like behavior in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflammation. 2016;13(1):231.

Sung N, Salazar Garcia MD, Dambaeva S, Beaman KD, Gilman-Sachs A, Kwak-Kim J. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues lead to pro-inflammatory changes in T lymphocytes. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2016;76(1):50–8.

Chassaing B, Koren O, Goodrich JK, Poole AC, Srinivasan S, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. Dietary emulsifiers impact the mouse gut microbiota promoting colitis and metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2015;519(7541):92–6.

Chassaing B, Aitken JD, Malleshappa M, Vijay-Kumar M. Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2014;104: Unit 15.25. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24510619.

Gabele E, Dostert K, Hofmann C, Wiest R, Scholmerich J, Hellerbrand C, Obermeier F. DSS induced colitis increases portal LPS levels and enhances hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis in experimental NASH. J Hepatol. 2011;55(6):1391–9.

Bruce-Keller AJ, Salbaum JM, Luo M, Blanchard E, Taylor CM, Welsh DA, Berthoud HR. Obese-type gut microbiota induce neurobehavioral changes in the absence of obesity. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77(7):607–15.

Caricilli AM, Picardi PK, de Abreu LL, Ueno M, Prada PO, Ropelle ER, Hirabara SM, Castoldi A, Vieira P, Camara NO, Curi R, Carvalheira JB, Saad MJ. Gut microbiota is a key modulator of insulin resistance in TLR 2 knockout mice. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(12):e1001212.

Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, Waget A, Delmee E, Cousin B, Sulpice T, Chamontin B, Ferrieres J, Tanti JF, Gibson GR, Casteilla L, Delzenne NM, Alessi MC, Burcelin R. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761–72.

Hansen MK, Nguyen KT, Fleshner M, Goehler LE, Gaykema RP, Maier SF, Watkins LR. Effects of vagotomy on serum endotoxin, cytokines, and corticosterone after intraperitoneal lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278(2):R331–6.

Finegold SM, Dowd SE, Gontcharova V, Liu C, Henley KE, Wolcott RD, Youn E, Summanen PH, Granpeesheh D, Dixon D, Liu M, Molitoris DR, Green JA 3rd. Pyrosequencing study of fecal microflora of autistic and control children. Anaerobe. 2010;16(4):444–53.

Nadal I, Donat E, Ribes-Koninckx C, Calabuig M, Sanz Y. Imbalance in the composition of the duodenal microbiota of children with coeliac disease. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56(Pt 12):1669–74.

Hsiao EY. Gastrointestinal issues in autism spectrum disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22(2):104–11.

Mazurek MO, Vasa RA, Kalb LG, Kanne SM, Rosenberg D, Keefer A, Murray DS, Freedman B, Lowery LA. Anxiety, sensory over-responsivity, and gastrointestinal problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013;41(1):165–76.

Gracie DJ, Williams CJ, Sood R, Mumtaz S, Bholah MH, Hamlin PJ, Ford AC. Poor correlation between clinical disease activity and mucosal inflammation, and the role of psychological comorbidity, in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(4):541–51.

Reigada LC, Satpute A, Hoogendoorn CJ, Cohen BH, Lai J, Bao R, Dubinsky MC, Benkov KJ. Patient-reported anxiety: a possible predictor of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease health care use. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(9):2127–33.

Lim SM, Kim DH. Bifidobacterium adolescentis IM38 ameliorates high-fat diet-induced colitis in mice by inhibiting NF-kappaB activation and lipopolysaccharide production by gut microbiota. Nutr Res. 2017;41:86–96.

Viennois E, Merlin D, Gewirtz AT, Chassaing B. Dietary emulsifier-induced low-grade inflammation promotes colon carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2017;77(1):27–40.

Jang SE, Lim SM, Jeong JJ, Jang HM, Lee HJ, Han MJ, Kim DH. Gastrointestinal inflammation by gut microbiota disturbance induces memory impairment in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 2017. Epub ahead of print. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28612842.

Firpo MA, Rollins MD, Szabo A, Gull JD, Jackson JD, Shao Y, Glasgow RE, Mulvihill SJ. A conscious mouse model of gastric ileus using clinically relevant endpoints. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005;5:18.

Hoggatt AF, Hoggatt J, Honerlaw M, Pelus LM. A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down: a novel technique to improve oral gavage in mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2010;49(3):329–34.

Iijima I, Minamikawa J, Jacobson AE, Brossi A, Rice KC. Studies in the (+)-morphinan series. 5. Synthesis and biological properties of (+)-naloxone. J Med Chem. 1978;21(4):398–400.

Marcoli M, Ricevuti G, Mazzone A, Pasotti D, Lecchini S, Frigo GM. A stereoselective blockade by naloxone of opioid and non-opioid-induced granulocyte activation. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1989;11(1):57–61.

Li Y, Zhang H, Zhang H, Kosturakis AK, Jawad AB, Dougherty PM. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling contributes to paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pain. 2014;15(7):712–25.

Vatanen T, Kostic AD, d'Hennezel E, Siljander H, Franzosa EA, Yassour M, Kolde R, Vlamakis H, Arthur TD, Hamalainen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Uibo R, Mokurov S, Dorshakova N, Ilonen J, Virtanen SM, Szabo SJ, Porter JA, Lahdesmaki H, Huttenhower C, Gevers D, Cullen TW, Knip M, Group DS, Xavier RJ. Variation in microbiome LPS immunogenicity contributes to autoimmunity in humans. Cell. 2016;165(6):1551.

Coats SR, Pham TT, Bainbridge BW, Reife RA, Darveau RP. MD-2 mediates the ability of tetra-acylated and penta-acylated lipopolysaccharides to antagonize Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide at the TLR4 signaling complex. J Immunol. 2005;175(7):4490–8.

Corrigan F, Wu Y, Tuke J, Coller JK, Rice KC, Diener KR, Hayball JD, Watkins LR, Somogyi AA, Hutchinson MR. Alcohol-induced sedation and synergistic interactions between alcohol and morphine: a key mechanistic role for Toll-like receptors and MyD88-dependent signaling. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;45:245–52.

Wu Y, Lousberg EL, Moldenhauer LM, Hayball JD, Coller JK, Rice KC, Watkins LR, Somogyi AA, Hutchinson MR. Inhibiting the TLR4-MyD88 signalling cascade by genetic or pharmacological strategies reduces acute alcohol-induced sedation and motor impairment in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(5):1319–29.

Sorge RE, LaCroix-Fralish ML, Tuttle AH, Sotocinal SG, Austin JS, Ritchie J, Chanda ML, Graham AC, Topham L, Beggs S, Salter MW, Mogil JS. Spinal cord Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory and neuropathic hypersensitivity in male but not female mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31(43):15450–4.

Cooley WL, P. R. Multivariate data analysis. Hoboken: Wiley; 1971.

Bishop CM. Neural networks for pattern recognition. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1995.

Ghani NAML, Liong CY, Jemain AA. Analysis of geometric moments as features for identification. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2009.

Perezgonzalez JD. Commentary: continuously cumulating meta-analysis and replicability. Front Psychol. 2015;6:565.

Wolfe R, Cumming G. Communicating the uncertainty in research findings: confidence intervals. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7(2):138–43.

Zager A, Brandao WN, Margatho RO, Peron JP, Tufik S, Andersen ML, Kornum BR, Palermo-Neto J. The wake-promoting drug modafinil prevents motor impairment in sickness behavior induced by LPS in mice: role for dopaminergic D1 receptor. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:468–76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28499899.

Mayerhofer R, Frohlich EE, Reichmann F, Farzi A, Kogelnik N, Frohlich E, Sattler W, Holzer P. Diverse action of lipoteichoic acid and lipopolysaccharide on neuroinflammation, blood-brain barrier disruption, and anxiety in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;60:174–87.

Ghisoni K, Aguiar AS Jr, de Oliveira PA, Matheus FC, Gabach L, Perez M, Carlini VP, Barbeito L, Mongeau R, Lanfumey L, Prediger RD, Latini A. Neopterin acts as an endogenous cognitive enhancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;56:156–64.

Sulakhiya K, Keshavlal GP, Bezbaruah BB, Dwivedi S, Gurjar SS, Munde N, Jangra A, Lahkar M, Gogoi R. Lipopolysaccharide induced anxiety- and depressive-like behaviour in mice are prevented by chronic pre-treatment of esculetin. Neurosci Lett. 2016;611:106–11.

Sulakhiya K, Kumar P, Gurjar SS, Barua CC, Hazarika NK. Beneficial effect of honokiol on lipopolysaccharide induced anxiety-like behavior and liver damage in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2015;132:79–87.

Haba R, Shintani N, Onaka Y, Wang H, Takenaga R, Hayata A, Baba A, Hashimoto H. Lipopolysaccharide affects exploratory behaviors toward novel objects by impairing cognition and/or motivation in mice: possible role of activation of the central amygdala. Behav Brain Res. 2012;228(2):423–31.

Zager A, Andersen ML, Lima MM, Reksidler AB, Machado RB, Tufik S. Modulation of sickness behavior by sleep: the role of neurochemical and neuroinflammatory pathways in mice. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;19(8):589–602.

Painsipp E, Herzog H, Holzer P. Implication of neuropeptide-Y Y2 receptors in the effects of immune stress on emotional, locomotor and social behavior of mice. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55(1):117–26.

Juszczak GR, Blaszczyk J, Sadowski B, Sliwa AT, Wolak P, Tymosiak-Zielinska A, Lisowski P, Swiergiel AH. Lipopolysaccharide does not affect acoustic startle reflex in mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(1):74–9.

Swiergiel AH, Dunn AJ. Effects of interleukin-1beta and lipopolysaccharide on behavior of mice in the elevated plus-maze and open field tests. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(4):651–9.

Lacosta S, Merali Z, Anisman H. Behavioral and neurochemical consequences of lipopolysaccharide in mice: anxiogenic-like effects. Brain Res. 1999;818(2):291–303.

Meijer MK, Spruijt BM, van Zutphen LF, Baumans V. Effect of restraint and injection methods on heart rate and body temperature in mice. Lab Anim. 2006;40(4):382–91.

Campos AC, Fogaca MV, Aguiar DC, Guimaraes FS. Animal models of anxiety disorders and stress. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2013;35(Suppl 2):S101–11.

Calabrese EJ. An assessment of anxiolytic drug screening tests: hormetic dose responses predominate. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2008;38(6):489–542.

Li Y, Adamek P, Zhang H, Tatsui CE, Rhines LD, Mrozkova P, Li Q, Kosturakis AK, Cassidy RM, Harrison DS, Cata JP, Sapire K, Zhang H, Kennamer-Chapman RM, Jawad AB, Ghetti A, Yan J, Palecek J, Dougherty PM. The cancer chemotherapeutic paclitaxel increases human and rodent sensory neuron responses to TRPV1 by activation of TLR4. J Neurosci. 2015;35(39):13487–500.

Doyle HH, Eidson LN, Sinkiewicz DM, Murphy AZ. Sex differences in microglia activity within the periaqueductal gray of the rat: a potential mechanism driving the dimorphic effects of morphine. J Neurosci. 2017;37(12):3202–14.

Shen H, Tesar BM, Walker WE, Goldstein DR. Dual signaling of MyD88 and TRIF is critical for maximal TLR4-induced dendritic cell maturation. J Immunol. 2008;181(3):1849–58.

Berin MC, Zheng Y, Domaradzki M, Li XM, Sampson HA. Role of TLR4 in allergic sensitization to food proteins in mice. Allergy. 2006;61(1):64–71.

Bashir ME, Louie S, Shi HN, Nagler-Anderson C. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling by intestinal microbes influences susceptibility to food allergy. J Immunol. 2004;172(11):6978–87.

Mazmanian SK, Liu CH, Tzianabos AO, Kasper DL. An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell. 2005;122(1):107–18.

Nishino R, Mikami K, Takahashi H, Tomonaga S, Furuse M, Hiramoto T, Aiba Y, Koga Y, Sudo N. Commensal microbiota modulate murine behaviors in a strictly contamination-free environment confirmed by culture-based methods. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25(6):521–8.

Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Microbiota is essential for social development in the mouse. Mol Psychiatry. 2014;19(2):146–8.

Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol. 2000;164(12):6166–73.

Thomas A, Burant A, Bui N, Graham D, Yuva-Paylor LA, Paylor R. Marble burying reflects a repetitive and perseverative behavior more than novelty-induced anxiety. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204(2):361–73.

Tuomisto L. Delayed ontogenesis of histamine in the hypothalamus of the homozygous Brattleboro rat. Agents Actions. 1986;18(1–2):219–21.

Balazsfi D, Pinter O, Klausz B, Kovacs KB, Fodor A, Torok B, Engelmann M, Zelena D. Restoration of peripheral V2 receptor vasopressin signaling fails to correct behavioral changes in Brattleboro rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:11–23.

Fodor A, Kovacs KB, Balazsfi D, Klausz B, Pinter O, Demeter K, Daviu N, Rabasa C, Rotllant D, Nadal R, Zelena D. Depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors and stress-related neuronal activation in vasopressin-deficient female Brattleboro rats. Physiol Behav. 2016;158:100–11.

Santos-Galindo M, Acaz-Fonseca E, Bellini MJ, Garcia-Segura LM. Sex differences in the inflammatory response of primary astrocytes to lipopolysaccharide. Biol Sex Differ. 2011;2:7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the GSU Department of Animal Resources for their expert animal care. We would also like to thank Nicole Peters, Jack Whylings, and Mary Holder Conklin for their advice on behavior testing. Additionally, we thank Nancy Forger and Forger lab members for their feedback on the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to CTF (R36 MH 112369), ATG (5 R01 DK 083890), and GJD (R21 MH 108345). BC is funded by the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation and by the Kenneth Rainin Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CTF, BC, ATG, and GJD conceived and designed the study. CTF and BC generated the colonies. CTF, RO, BC, and ACR performed the research and data analysis. CTF wrote the manuscript. CTF, ATG, and GJD funded the research. ATG and GJD provided scientific guidance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All work was carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Georgia State University and in conformance with principles enunciated in the NIH Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Title: Independent ANOVAs from Experiment 1 suggest outcome variables that contribute to group differences highlighted by Pillai’s trace. Legend: Individual ANOVAs on outcome variables measured in Experiment 1. Significant results are boldfaced. F values are indicated in the “F” column, p values are indicated in the “Sig.” column and effect sizes (partial eta squared) are indicated in the “Partial η^2” column. For each ANOVA, hypothesis degrees of freedom is 1 and error degrees of freedom is 18. (DOCX 16 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Title: Original classification and cross-validation of discriminant functions for Experiment 1. Legend: Validation of discriminant functions for Experiment 1 by original case classification and leave-one-out cross validation. 100% of the original grouped cases are correctly classified by the discriminant functions. In the leave-one-out cross-validation test, the discriminant functions are recalculated excluding one case, and all cases are recalculated. This algorithm is repeated for the exclusion of each case. In the leave-one-out test, 63.6% of cross-validated grouped cases were correctly classified. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Title: Independent ANOVAs from Experiment 2 suggest outcome variables that contribute to group differences highlighted by Pillai’s trace. Legend: Individual ANOVAs on outcome variables measured in Experiment 2. Significant results are boldfaced. Trends are italicized. F values are indicated in the “F” column, p values are indicated in the “Sig.” column and effect sizes (partial eta squared) are indicated in the “Partial η^2” column. For each ANOVA, hypothesis degrees of freedom is 1 and error degrees of freedom is 111. (DOCX 39 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S4.

Title: Original classification and cross-validation of discriminant functions for Experiment 2 for cases grouped by gavage treatment and sex. Legend: Validation of discriminant functions for Experiment 2, for cases grouped by gavage treatment and sex, by original case classification and leave-one-out cross validation. 64.6% of the original grouped cases are correctly classified by the discriminant functions. In the leave-one-out cross-validation test, the discriminant functions are recalculated excluding one case, and all cases are recalculated. This algorithm is repeated for the exclusion of each case. In the leave-one-out test, 45.7% of cross-validated grouped cases were correctly classified. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S5.

Title: Original classification and cross-validation of discriminant functions for Experiment 1. Legend: Validation of discriminant functions for Experiment 2, for cases grouped by (+)-naloxone treatment and sex, by original case classification and leave-one-out cross validation. 65.4% of the original grouped cases are correctly classified by the discriminant functions. In the leave-one-out cross-validation test, the discriminant functions are recalculated excluding one case, and all cases are recalculated. This algorithm is repeated for the exclusion of each case. In the leave-one-out test, 48.0% of cross-validated grouped cases were correctly classified. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 6: Figure S1.

Title: Meta-analysis of serum endotoxin levels in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in serum endotoxin levels between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 7: Figure S2.

Title: Meta-analysis of ambulatory episodes in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in ambulatory episodes between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 8: Figure S3.

Title: Meta-analysis of ambulatory time in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in ambulatory time between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 9: Figure S4.

Meta-analysis of ambulatory distance in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in ambulatory distance between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 10: Figure S5.

Meta-analysis of resting time in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in resting time between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 11: Figure S6.

Meta-analysis of average velocity in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in average velocity between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 12: Figure S7.

Meta-analysis of zone entries in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in zone entries between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 13: Figure S8.

Meta-analysis of stretch posture in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in time in stretch posture between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 14: Figure S9.

Meta-analysis of jump counts in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in jump counts between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 15: Figure S10.

Meta-analysis of jump time in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in jump time between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 16: Figure S11.

Meta-analysis of clockwise reversals in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in clockwise reversals between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 17: Figure S12.

Meta-analysis of counter-clockwise reversals in WT males of Experiments 1 and 2. Legend: Forest plot of difference in counter-clockwise reversals between male WT subjects gavaged with saline or LPS, measured from Experiment 1 (top green bar) and Experiment 2 (bottom green bar). The result of the meta-analysis is indicated by the red diamond. The width of the green bars and the red diamond indicate the range of the 95% confidence intervals for each, with the center representing the mean. WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists were used for these analyses (total n = 15/group). See Additional file 18: Table S7 for statistics. (PPTX 45 kb)

Additional file 18: Table S6.

Meta-analysis of behavioral outcomes for WT males not treated with TLR4 antagonists (n = 15/group). Legend: 95% confidence interval values for Experiment 1, Experiment 2, and the meta-analysis. UL = Upper Limit. LL = Lower Limit. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fields, C.T., Chassaing, B., Castillo-Ruiz, A. et al. Effects of gut-derived endotoxin on anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors in male and female mice. Biol Sex Differ 9, 7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-018-0166-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-018-0166-x