Abstract

Background

Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, acts as an inhibitor of angiogenesis and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. Administration of stem cells may affect endogenous mechanisms that regulate ADMA production and metabolism. The aim of the present study was to analyze ADMA concentration and changes in oxidative stress in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia (CLI) after bone marrow-derived mononuclear cell (BM-MNC) therapy.

Methods

Fifty patients (age 64 ± 11 years, 44 males, 6 females) with advanced CLI (Rutherford category 5 or 6) not eligible for revascularization were treated by intramuscular (n = 25) or intra-arterial (n = 25) injection of 40 ml BM-MNC concentrate. Patients with limb salvage and improved wound healing after 6 months were considered responders to cell therapy. The concentrations of markers of oxidative stress and angiogenesis were analyzed before, and at 3 and 6 months after BM-MNC delivery.

Results

At 6-month follow-up, four patients died of reasons unrelated to stem cell therapy. Among the survivors, 80% (37/46) showed limb salvage and improved wound healing. At 6 months follow-up, ADMA concentration significantly decreased in patients with limb salvage (1.74 ± 0.66 to 0.90 ± 0.49 μmol/L, p < 0.001), in parallel with decreased tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (2.22 ± 0.16 to 1.94 ± 0.38 pg/ml, p < 0.001), and increased reduced glutathione (6.96 ± 3.1 to 8.67 ± 4.2 μmol/L, p = 0.02), superoxide dismutase activity (168 ± 50 to 218 ± 37 U/L, p = 0.002), and coenzyme Q10 concentration (468 ± 182 to 598 ± 283 μg/L, p = 0.02). The number of delivered BM-MNCs significantly correlated with the decrease in ADMA concentration at 3 months (p = 0.004, r = −0.48) and the decrease in TNF-α concentration at 6 months (p = 0.03, r = −0.44) after cell delivery. ADMA or TNF-α improvement did not correlate with the number of applied CD34+ cells, C-reactive protein concentration, leukocyte count, or the dose of atorvastatin.

Conclusions

The therapeutic benefit of BM-MNC therapy is associated with reduced ADMA levels and oxidative stress. Regulation of the ADMA-nitric oxide axis and improved antioxidant status may be involved in the beneficial effects of stem cell therapy.

Trial registration

The study was approved and retrospectively registered by ISRCTN registry, ISRCTN16096154. Registered on 26 July 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase (NOS), regulates the rate of nitric oxide (NO) formation, acts as an inhibitor of angiogenesis, and is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1,2,3,4]. Increased ADMA plasma concentrations predict major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with advanced peripheral artery disease [5]. Increased oxidative stress contributes to elevated ADMA. In turn, increased serum ADMA concentration is associated with increased vascular oxidative stress, as demonstrated by the upregulation of circulating markers of oxidative stress. The precise relationship between serum ADMA and oxidative stress remains unclear. The enzyme responsible for ADMA degradation, dimethylarginine dimethlyaminohydrolase (DDAH), is redox-sensitive as its activity decreases in the presence of increased oxidative stress. Therefore, oxidative stress increases ADMA synthesis and inhibits its degradation [6,7,8] (Fig. 1). Preclinical models indicate that antioxidant therapy improves neovascularization when given in combination with bone marrow-derived mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) [9,10,11].

The aim of the present study was to analyze ADMA concentration and changes in oxidative stress in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia (CLI) in response to BM-MNC therapy.

Methods

Patients

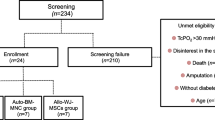

Fifty patients (age 64 ± 11 years, 44 males, 6 females) with advanced CLI (Rutherford category 5 or 6) who were not eligible for revascularization were treated by intramuscular (IM) (n = 25) or intra-arterial (IA) (n = 25) injection of 40 ml BM-MNC concentrate. The mode of application was based on computerized randomization with equal sex and diabetes mellitus distribution in both groups. The etiology of arterial obliteration was atherosclerosis in 45 patients and thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger disease) in 5 patients.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: 1) patients over 18 years of age with ischemic skin lesions (ulcer or gangrene) and Rutherford category 5 or 6 CLI according to the TASC classification (minor or major tissue loss) [12]; 2) CLI defined by ankle-brachial index ≤0.4, or ankle systolic pressure <50 mmHg, or toe systolic pressure <30 mmHg, and transcutaneous oxygen pressure (tcpO2) <30 mmHg; and 3) no option for endovascular or surgical revascularization as determined by both vascular surgeon and interventionalist.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were: 1) life expectancy of <6 months; 2) evidence of malignancy during the previous 5 years; 3) critical coronary artery disease or unstable angina pectoris; 4) end-stage kidney disease; and 5) bone marrow disease, e.g., myelodysplastic syndrome, severe anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia.

Method of BM-MNC isolation and administration

Under analgosedation with propofol, a total of 240 ml bone marrow was harvested from both posterior iliac crests. The bone marrow aspirate was processed with the SmartPreP2 Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate System (Harvest, Plymouth, MA, USA). The system uses gradient density centrifugation to provide 40 ml of bone marrow product rich for all blood elements within 15 min. The final product is defined by mix of cell types, including lymphocytoid cells, erythroblasts, monocytoid cells, and granulocytes. The mean nucleated cell count is about 100 × 106/ml. Bone marrow leukocytes and platelets are concentrated five- to sevenfold, and red cells are depleted to a hematocrit of less than 5%. Up to 99% of cells are viable after centrifugation [13,14,15]. After centrifugation, the cell concentrate was administered either by IM application (under analgosedation with propofol by deep IM injection of approximately 1 ml into the muscles of the affected limb along the crural arteries), or by IA infusion (injection of 40 ml of cell concentrate with a percutaneous femoral approach using a 4 F catheter at the site of arterial occlusion of the affected limb at a rate of 800 ml/h).

Preprocedural assessment and follow-up

All patients were examined before, at 90 days, and at 6 months after BM-MNC delivery. Peripheral blood tests such as blood count and assessment of basal serological parameters, including C-reactive protein (CRP), were performed. Venous blood samples were collected for the determination of circulating markers of oxidative stress. The concentrations of ADMA (by Human, ADMA ELISA Kit; Sunlong Biotech Co. Ltd, Zhejiang, China), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6 (all by Quantikine ELISA; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK), apolipoprotein A (Apo(a)), and oxidized low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL) were assessed using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (both supplied by antibodies-online Inc., Atlanta, USA). The levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), reduced glutathione (GSH), vitamin C, vitamin E, coenzyme Q10, and retinol were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography. Protein carbonyls (PC) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity were measured spectrophotometrically (reagents by Randox Laboratories Ltd., Crumlin, UK). DNA fragmentation was assessed using comet assays. The ferric reducing ability of plasma was evaluated by ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) assay. The total antioxidant status (TAS; colorimetric kit by Randox Laboratories Ltd., Crumlin, UK) and total peroxide concentration of plasma (by OxyStat ELISA, Biomedica Medizinprodukte GmbH & CO KG, Vienna, Austria) were estimated.

In the bone marrow concentrate the total concentration of mononuclear cells and CD34+ cells was evaluated.

The following characteristics of limb ischemia were detected. Measurement of the resting ankle-brachial index (ABI) was performed according to validated standards [16]. TcpO2 of the affected limb was assessed using a TCM400 Mk2 monitor (Radiometer Medical ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark). TcpO2 was measured at the forefoot in the supine position with an electrode at a temperature of 44°C. Wound characteristics were documented by digital photography. Wound healing was evaluated by two independent physicians. The pain score was determined using a visual analog scale (VAS) and graded 0–10. Patients were discharged the day after the procedure on dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin plus clopidogrel) and on statin therapy. All patients received conventional wound care during follow-up.

Clinical outcomes

Patients with limb salvage and improvement in wound healing at 6 months were considered responders to cell therapy. Limb salvage was defined as the absence of amputation above the ankle joint. Other functional limb ischemia outcomes included in the evaluation were change in tcpO2, Rutherford category, and pain score after cell transplantation. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the National Institute of Cardiovascular Diseases, Bratislava. All included patients were informed about the nature of the study and gave their written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Data evaluation was performed using the statistical software package SPSS v21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Discrete variables are presented as counts and percentages. Gaussian distributions of data were tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD. For comparisons between the baseline and 6-month follow-up values, the paired Student t test was used for normally distributed values, Wilcoxon matched pairs test for nonparametric variables, and McNemar's test for categorical variables. For correlation analyses, Pearson’s r was calculated for normally distributed values and Spearman’s r was calculated for nonGaussian variables. For all analyses, a two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the patient population are listed in Table 1. During the 6 months of follow-up, four patients died of causes unrelated to stem cell application. In nine of the 46 surviving patients, major limb amputation was required because of CLI progression. At 6-month follow-up, 80% (37/46) of patients showed limb salvage and improved wound healing. The amputation-free survival endpoint was met in 74% (37/50) of patients, with no difference between IM versus IA application (72% vs. 76%, p = 1.0). Table 2 shows the parameters of limb ischemia in patients with limb salvage at 6 months. There was significant improvement in tcpO2, pain score, and CLI Rutherford category, whereas there was no difference in the ABI parameter.

Patients with limb salvage after cell therapy showed a significant decrease in ADMA concentration after 6 months (1.74 ± 0.66 to 0.90 ± 0.49 μmol/l, p < 0.001) and a significant decrease in TNF-α (2.22 ± 0.16 to 1.94 ± 0.38 pg/ml, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Table 4 shows biomarkers of oxidative stress in patients with limb salvage after cell therapy. There was a significant improvement in selected markers of antioxidant capacity (Apo(a), SOD, GSH, retinol, and coenzyme Q10), whereas improvements in other antioxidant parameters were borderline (vitamin C and vitamin C/vitamin E ratio). Serum levels of antioxidant markers FRAP and TAS remained unchanged at 6 months. Protein carbonyls decreased, whereas other markers of oxidative damage (MDA, oxLDL, and DNA fragmentation) showed no changes.

The serum concentration of ADMA before cell delivery correlated with VEGF levels (p < 0.001, r = 0.48). The dose of delivered BM-MNCs significantly correlated with the reduction in ADMA concentration at 3 months after cell application (p = 0.004, r = −0.48) (Fig. 3), TNF-α concentration at 6 months (p = 0.03, r = −0.44), and the decrease in peripheral leukocyte count at 3 months (p = 0.005, r = −0.52) and 6 months after cell delivery (p = 0.002, r = −0.51). There was no correlation between ADMA change and the number of applied CD34+ cells, CRP concentration, leukocyte count, or the dose of atorvastatin. No changes in homocysteine level, serum creatinine concentration, leukocytes, or IL-6 levels were observed between before and at 6 months after cell delivery (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of stem cell therapy on circulating ADMA levels and markers of oxidative stress in patients with CLI. The main findings can be summarized as follows: 1) BM-MNCs were associated with a significant reduction in serum ADMA levels, as well as TNF-α, and this was related to the dose of mononuclear cells; 2) BM-MNC therapy was associated with a reduction in the markers of oxidative stress. Taken together, these data indicate that regulation of the ADMA-NO axis and improvement of antioxidant balance may be involved in the beneficial effects of stem cell therapy in CLI patients.

Patients with limb salvage and improvement in wound healing at 6 months were defined as responders to cell therapy. Our mechanistic study is designed as a single arm mechanistic study without the control group. In addition, therapeutic benefit in terms of limb salvage and wound healing varies among various studies due to the number of modifying factors such as diabetes, renal failure, or extent of tissue loss. Nevertheless, our rates of therapeutic benefit (19.5% limb amputations) scores better as compared to the reported frequency of major limb amputation in a similar control, untreated population [17],

There was no difference between IA and IM application in all clinical parameters during follow-up. Likewise, there was no difference in all important measured parameters. Our results from a direct head-to-head comparison indicate that IM and IA methods of bone marrow cell delivery are effective for limb salvage and wound healing, with no significant differences in various functional surrogate endpoints between the techniques [18].

ADMA acts as an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis by impairing the NOS/NO pathway and NO bioavailability. High concentrations of ADMA are associated with low levels of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), suppressing their mobilization and differentiation [19]. Circulating EPCs are reduced and dysfunctional in various diseases in parallel with increased ADMA levels, such as diabetes, coronary heart disease, peripheral artery disease, and ischemic stroke. The reduction in ADMA levels might accelerate endothelial regeneration by promoting the mobilization of bone marrow-derived endothelial cells [20]. In our study, ADMA levels decreased proportionally to the dose of BM-MNCs suggesting a possible mechanistic link underlying the beneficial effect of cell therapy. ADMA is eliminated largely by the action of DDAH. As the activity of DDAH is typically reduced in conditions associated with oxidative stress, it is attractive to hypothesize that administration of BM-MNCs could modulate the ADMA concentration by increasing DDAH activity. This hypothesis warrants further mechanistic validation.

In addition, ADMA correlates with oxidative stress markers. Administration of ADMA significantly increases intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and reduces antioxidant capacity by decreasing SOD, catalase, and GSH activity [21]. On the other hand, oxidative stress increases ADMA synthesis and decreases its degradation. Corroborating these reports, our findings indicate a significant improvement in selected markers of antioxidant capacity or oxidative damage (Apo(a), SOD, GSH, retinol, coenzyme Q10, protein carbonyls) in parallel with a reduction in serum ADMA levels. Improvements in other antioxidant parameters were borderline or absent. Although improvements in selected parameters were more pronounced after IM application, it did not translate to a superior effect on surrogated or clinical outcomes.

TNF-α, an inflammatory cytokine involved in atherogenesis, is secreted from various cells including monocytes. ADMA increases the production of intracellular ROS and induces TNF-α expression. In our observations, the plasma levels of both ADMA and TNF-α decreased after cell application in correlation with the amount of cells administered and concomitant with the improvement of antioxidant status. Importantly, the decrease in ADMA levels did not correlate with parameters of inflammation, such as CRP, IL-6, or leukocyte concentration. Whether the application of BM-MNCs directly improved oxidative stress, with a subsequent positive influence on DDAH activity, ADMA concentration, and TNF-α, remains unclear from our data. Another possibility is that cell delivery decreased ADMA concentration, with further improvement in TNF-α activity and oxidative stress. Both mechanisms can be present simultaneously.

Limitations

The main limitation of the study was the lack of a control group of “no-option” CLI patients who did not receive BM-MNCs. Another limitation was the relatively small number of treated patients. However, the current findings are hypothesis-generating for future larger, controlled trials. Additionally, evaluation of DDAH activity may be useful to clarify the important association between ADMA concentration and stem cell application.

Conclusions

The goal of stem cell therapy in ischemic syndromes is to restore the vitality and functionality of ischemic tissues. Administration of BM-MNCs could positively affect tissue regeneration in CLI patients by decreasing ADMA concentration and attenuating oxidative stress. Regulation of the ADMA-NO axis and the ADMA synthesis pathway may represent a promising therapeutic target for stem cell therapy in regenerative interventions for cardiovascular diseases.

Abbreviations

- ABI:

-

Ankle-brachial index

- ADMA:

-

Asymmetric dimethylarginine

- Apo(a):

-

Apolipoprotein A

- BM-MNC:

-

Bone marrow-derived mononuclear cell

- CLI:

-

Critical limb ischemia

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- DDAH:

-

Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- EPC:

-

Endothelial progenitor cell

- FRAP:

-

Ferric reducing ability of plasma

- GSH:

-

Reduced glutathione

- IA:

-

Intra-arterial

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IM:

-

Intramuscular

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- oxLDL:

-

Oxidized low-density lipoproteins

- PC:

-

protein carbonyls

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TAS:

-

Total antioxidant status

- tcpO2 :

-

Transcutaneous oxygen pressure

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

Zhang P, Hu X, Xu X, Chen Y, Bache RJ. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 modulates endothelial cell growth through nitric oxide and Akt. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:890–7.

Jang JJ, Ho HK, Kwan HH, Fajardo LF, Cooke JP. Angiogenesis is impaired by hypercholesterolemia: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine. Circulation. 2000;102:1414–9.

Boger RH, Sullivan LM, Schwedhelm E, Wang TJ, Maas R, Benjamin EJ, Schulze F, Xanthakis V, Benndorf RA, Vasan RS. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine and incidence of cardiovascular disease and death in the community. Circulation. 2009;119:1592–600.

Mangiacapra F, Conte M, Demartini C, Muller O, Delrue L, Dierickx K, Di Sciascio G, Trimarco B, De Bruyne B, Wijns W, Bartunek J, Barbato E. Relationship of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) with extent and functional severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;220:629–33.

Mittermayer F, Krzyzanowska K, Exner M, Mlekusch W, Amighi J, Sabeti S, Minar E, Müller M, Wolzt M, Schillinger M. Asymmetric dimethylarginine predicts major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with advanced peripheral artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2536–40.

Sydow K, Münzel T. ADMA and oxidative stress. Atheroscler Suppl. 2003;4:41–51. Review.

Leiper J, Murray-Rust J, McDonald N, Valance P. S-nitrosylatio of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulates enzyme activity: further interactions between nitric oxide synthase and dimethylarginine dimethylaminodyhdrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13527–32.

Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Leeson P, Antonopoulos A, Warrick N, Van-Assche T, Cunnington C, Tousoulis D, Pillai R, Ratnatunga C, Stefanadis C, Channon KM. Association of plasma asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA) with elevated vascular superoxide production and endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling: implications for endothelial function in human atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1142–50.

de Nigris F, Balestrieri ML, Williams-Ignarro S, D’Armiento FP, Lerman LO, Byrns R, Crimi E, Palagiano A, Fatigati G, Ignarro LJ, Napoli C. Therapeutic effects of autologous bone marrow cells and metabolic intervention in the ischemic hindlimb of spontaneously hypertensive rats involve reduced cell senescence and CXCR4/Akt/eNOS pathways. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2007;50:424–33.

Napoli C, Williams-Ignarro S, de Nigris F, de Rosa G, Lerman LO, Farzati B, Matarazzo A, Sica G, Botti C, Fiore A, Byrns RE, Sumi D, Sica V, Ignarro LJ. Beneficial effects of concurrent autologous bone marrow cell therapy and metabolic intervention in ischemia-induced angiogenesis in the mouse hindlimb. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17202–6.

Sica V, Williams-Ignarro S, de Nigris F, D’Armiento FP, Lerman LO, Balestrieri ML, Maione C, Palagiano A, Rossiello L, Ignarro LJ, Napoli C. Autologous bone marrow cell therapy and metabolic intervention in ischemia-induced angiogenesis in the diabetic mouse hindlimb. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2903–8.

Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG, TASC II Working Group, Bell K, Caporusso J, Durand-Zaleski I, Komori K, Lammer J, Liapis C, Novo S, Razavi M, Robbs J, Schaper N, Shigematsu H, Sapoval M, White C, White J, Clement D, Creager M, Jaff M, Mohler 3rd E, Rutherford RB, Sheehan P, Sillesen H, Rosenfield K. Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;33 Suppl 1:S1–75.

Amann B, Luedemann C, Ratei R, Schmidt-Lucke JA. Autologous bone marrow cell transplantation increases leg perfusion and reduces amputations in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia due to peripheral artery disease. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:371–80.

Procházka V, Gumulec J, Jalůvka F, Salounová D, Jonszta T, Czerný D, Krajča J, Urbanec R, Klement P, Martinek J, Klement GL. Cell therapy, a new standard in management of chronic critical limb ischemia and foot ulcer. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:1413–24.

Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, von Hesler C, Andrassy J, Kevy SV, Jacobson MS, Heeschen C. Concentration of bone marrow total nucleated cells by a point-of-care device provides a high yield and preserves their functional activity. Cell Transplant. 2008;16:1059–69.

Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, Johnston KW, Porter JM, Ahn S, Jones DN. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: revised version. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:517–38.

Benoit E, O'Donnell TF, Patel AN. Safety and efficacy of autologous cell therapy in critical limb ischemia: a systematic review. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(3):545–62.

Klepanec A, Mistrik M, Altaner C, Valachovicova M, Olejarova I, Slysko R, Balazs T, Urlandova T, Hladikova D, Liska B, Tomka J, Vulev I, Madaric J. No difference in intra-arterial and intramuscular delivery of autologous bone marrow cells in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia. Cell Transplant. 2012;21(9):1909–18.

Thum T, Tsikas D, Stein S, Schultheiss M, Eigenthaler M, Anker SD, Poole-Wilson PA, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. Suppression of endothelial progenitor cells in human coronary artery disease by the endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1693–701.

Konishi H, Sydow K, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase promotes endothelial repair after vascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1099–105.

Zhang GG, Bai YP, Chen MF, Shi RZ, Jiang DJ, Fu QM, Tan GS, Li YJ. Asymmetric dimethylarginine induces TNF-alpha production via ROS/NF-kappaB dependent pathway in human monocytic cells and the inhibitory effect of reinioside C. Vascul Pharmacol. 2008;48:115–21.

Funding

This study was sponsored by a grant from European Regional Development Funding (ITMS code: 26240220023).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JM wrote the manuscript, and designed and coordinate the study. JM, MV, JP, RM, KS, TM, and LPo acquired and interpreted the data. LPa provided statistical analysis. AK, IV, and JM performed angiography and indications. MM and JM performed stem cell isolation and administration. MV, JP, and RM provided laboratory analyses. TM, JM, and IV provided follow-up. All authors critically read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approved by the Ethical Committee of National Institute of Heart and Vascular Diseases (Slovakia), 7 August 2009, ref: 24209. All included patients were informed about the nature of the study and gave their written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Madaric, J., Valachovicova, M., Paulis, L. et al. Improvement in asymmetric dimethylarginine and oxidative stress in patients with limb salvage after autologous mononuclear stem cell application for critical limb ischemia. Stem Cell Res Ther 8, 165 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-017-0622-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-017-0622-2