Abstract

Background

Meningeal melanocytoma is a rare pigmented tumor arising from leptomeningeal melanocytes. Patients with this tumor might initially consult a dentist because a mass lesion in Meckel’s cave could manifest as dental pain and malocclusion, thereby mimicking temporomandibular disorder. The diagnostic approach, especially using imaging modalities, would be challenging in such cases unless an interdisciplinary approach is used.

Case presentation

Here, we report a case of a 39-year-old Japanese man who had a history of pain and numbness on the left side of his face and malocclusion for 3 months before the initial visit. The diagnosis was primary intracranial meningeal melanocytoma arising from Meckel’s cave.

Conclusions

The process by which the final diagnosis of meningeal melanocytoma was reached highlights the importance of collaboration between the medical and dental disciplines. This case also demonstrates that meningeal melanocytoma has a specific signal pattern on magnetic resonance imaging, including high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Meningeal melanocytoma is a benign pigmented tumor of the central nervous system [1]. This tumor is so rare that its incidence has yet to be reported, and there are few reports on such tumors in the English language literature [2]. The posterior fossa is the most common site involved. To date, there are only three reports of this tumor arising in Meckel’s cave and detailed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) descriptions are available for only four patients. Here we report the MRI findings in a patient with primary intracranial meningeal melanocytoma (IMM) arising from Meckel’s cave.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old Japanese man presented with a 3-month history of numbness on the left side of his face. His symptoms had gradually progressed and had become painful in the month before the initial visit. He also complained that sometimes he could not chew on the left side. An examination revealed decreased sensation over the distribution of the left trigeminal nerve that did not respond to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or muscle relaxants and was only slightly responsive to carbamazepine. His symptoms were associated with dyskinesia of the left masticatory muscles but there was no clicking sound. His facial expression was symmetrical at rest.

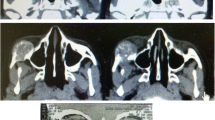

His past medical history was significant for acute gastritis, duodenal ulcer, and depression, for which brotizolam, flunitrazepam, and paroxetine had been prescribed, respectively. He was reticent and had difficulty communicating his feelings and wishes, which appeared to be related to his history of depression. Panoramic radiography revealed no specific findings relevant to his symptoms (Fig. 1a) but did identify slight restriction of movement of the temporomandibular joint on the left (Fig. 1b). MRI of the temporomandibular joint region was inconclusive for temporomandibular disorder and his symptoms were nonspecific for trigeminal neuralgia. Therefore, we extended the scanning range into the brain region and found a tumor measuring 10 mm in diameter and a homogeneously high signal intensity on axial T1-weighted images compared with gray matter (Fig. 2a) and low signal on axial T2-weighted images (Fig. 2b) in Meckel’s cave. The tumor appeared to be exerting pressure on his trigeminal nerve. He was referred to the neurosurgery department where unenhanced computed tomography (CT) images demonstrated a localized well-defined mass lesion in Meckel’s cave, which was homogeneously hyperdense compared with gray matter. No calcification was present (Fig. 3).

Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating a tumor 10 mm in diameter. a T1-weighted axial images (repetition time 667/echo time 9) revealed a homogeneously high signal tumor in Meckel’s cave. b T2-weighted axial images (repetition time 5200/echo time 98) revealed a low signal tumor exerting pressure on trigeminal nerve

En bloc excision was subsequently performed. Immunohistochemistry was positive for melanocytic features of Melan A (MART1; melanoma antigen recognized by T cells-1), human melanoma black-45, vimentin, and S-100 protein and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and glia fibrillary acidic protein (Fig. 4). Cellular proliferation was assessed by staining for Ki-67, which was positive, but the index was as low as 1–5%. These findings were associated with proliferation of tumor cells that contained abundant melanin pigment. Based on the above pathology results, a definitive diagnosis of melanocytoma was made.

Following excision of the intracranial tumor, our patient underwent adjuvant gamma knife radiosurgery with 24 Gy in two fractions to the tumor bed in the epidural space of the middle cranial fossa. No chemotherapy was administered. His postoperative course was uneventful with progressive resolution of the neurologic deficits. At follow-up 6.5 years later, he remains well with no signs of recurrence.

Discussion

Our case highlights two notable aspects of IMM. First, it illustrates the importance of close collaboration between medical and dental professionals in such cases, in that it was not until a neurosurgery referral was made that a definitive diagnosis of IMM was made. Second, we provide detailed information regarding the appearance of this kind of tumor on MRI.

Including the case described here, 14 cases of IMM with detailed MRI descriptions are documented in the English literature (Table 1). However, our case of IMM is the first in which the initial presentation was to a dentist, which highlights the fact that a mass lesion in Meckel’s cave can mimic temporomandibular disorder by manifesting clinically as pain and malocclusion, leading the patient to visit a dentist first. Observed from one side only, the lesion was difficult to identify. Subsequent examination prompted further investigation to find the underlying cause. The final diagnosis of IMM was reached and satisfactorily managed only by collaboration between dental and medical practitioners.

The most prominent radiologic feature in this case was the pattern seen on MRI, namely, high signal intensity on T1-weighted images and low signal intensity on T2-weighted images compared with gray matter, which suggests melanoma or melanocytoma arising in the intracranial region. Eleven of the 14 IMM cases summarized in Table 1 showed the same MRI pattern of high signal on T1-weighted images and low signal on T2-weighted images [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], and the others demonstrated a similar signal pattern [11,12,13]. Knowledge of the characteristic imaging features of this infrequently encountered tumor, particularly the signal characteristics on MRI, can greatly assist in narrowing the differential diagnosis. The differential diagnosis is reported to include pigmented meningioma, melanotic schwannoma, and primary or secondary malignant melanoma [2]. Like meningioma, melanocytoma tends to be a solitary lesion, is often attached to the underlying dura, and may be locally invasive. IMM tends to occur in the posterior fossa and in the cerebellopontine angle, so may be difficult to differentiate from schwannoma [2]. Consistent with the reports by Hamasaki et al. [2] and Offiah and Laitt [3], our case showed homogeneous hyperdensity compared with gray matter on CT images.

Conclusions

The case presented here underscores two important clinical issues in the diagnosis and treatment of IMM, namely, the importance of collaboration between medical and dental practitioners and the distinctive pattern of signal intensities on MRI. An interdisciplinary approach should be considered when such cases are encountered.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- IMM:

-

Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Pan H, Wang H, Fan Y. Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma associated with nevus of Ota. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1548–50.

Hamasaki O, Nakahara T, Sakamoto S, Kutsuna M, Sakoda K. Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2002;42:504–9.

Offiah CJ, Laitt RD. Case report: Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma: a cause of high signal on T1- and low signal on T2-weighted MRI. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:294–8.

Chen CJ, Hsu YI, Ho YS, Hsu YH, Wang LJ, Wong YC. Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma: CT and MRI. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:811–4.

Srirama Jayamma S, Sud S, Buxi TBS, Madan VS, Goyal A, Dhawan S. Cervical spinal meningeal melanocytoma presenting as intracranial superficial siderosis. Case Rep Radiol. 2015;2015:674868.

Lee JK, Rho YJ, Jeong DM, Rhim SC, Kim SJ. Diagnostic clue of meningeal melanocytoma: case report and review of literature. Yonsei Med J. 2017;58:467–70.

Lee NK, Lee JY, Wang KC, Kim DG, Park SH, Cheon JE, Phi JH, Kim SK. Primary atypical melanocytoma arising from the cavernous sinus in a child. Childs Nerv Syst. 2015;31:1577–82.

Lin B, Yang H, Qu L, Li Y, Yu J. Primary meningeal melanocytoma of the anterior cranial fossa: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:135.

Painter TJ, Chaljub G, Sethi R, Singh H, Gelman B. Intracranial and intraspinal meningeal melanocytosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1349–53.

Ruelle A, Tunesi G, Andrioli G. Spinal meningeal melanocytoma. Case report and analysis of diagnostic criteria. Neurosurg Rev. 1996;19:39–42.

Faro SH, Koenigsberg RA, Turtz AR, Croul SE. Melanocytoma of the cavernous sinus: CT and MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17:1087–90.

de Tella OI Jr, Agner C, Aguiar PH, Herculano MA, Prandini MN, Stavile JN. Aggressive management of orbital meningeal melanocytoma. Acta Neurochir. 2003;145:1121–6.

Tregnago AC, Furlan MV, Bezerra SM, Porto GC, Mendes GG, Henklain JV, Pinto CA, Kowalski LP, de Carvalho GB, Costa FD. Orbital melanocytoma completely resected with conservative surgery in association with ipsilateral nevus of Ota: report of a case and review of the literature. Head Neck. 2015;37:E49–55.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Taki from the Department of Neurosurgery, Kansai Rosai Hospital, Hyogo, Japan, for accepting the patient and providing the neurosurgical information included in this manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated for this case report (including clinical records, surgical records, pictures, and investigations) are available in the repository of Osaka Dental University, Osaka, Japan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HY made the decision to publish this report. Surgical management of the case was undertaken by TN, KT, and HY, who also contributed to compilation of the sections in the manuscript related to the maxillofacial surgery performed in this patient. SG contributed significantly to preparation of the manuscript and table as well as the selection of images. The neurosurgical aspects of the case were summarized by TT. SK and KS undertook a thorough review of the relevant literature. HA restructured and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a case report and there is no need for ethical approval.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent form is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gamoh, S., Tsuno, T., Akiyama, H. et al. Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma diagnosed using an interdisciplinary approach: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 12, 177 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1725-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1725-9