Abstract

Background

Secondary cervical dystonia is induced by organic brain lesions involving the basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum, and brain stem. It is extremely rare to see cervical dystonia induced by a medullary lesion.

Case presentation

We report a case of an 86-year-old Japanese woman who developed cervical dystonia following lateral medullary infarction. She developed sudden-onset left upper and lower extremity weakness, right-side numbness, and dysarthria. Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed an acute ischemic lesion involving the left lateral and dorsal medullae. A few days after her stroke, she complained of a taut sensation in her left neck and body, and cervico-shoulder dystonia toward the contralateral side subsequently appeared. Within a few weeks, it disappeared spontaneously, but her hemiplegia remained residual.

Conclusions

To date, to the best of our knowledge, there has been only one reported case of cervical dystonia associated with a single medullary lesion. It is interesting to note the similarities in the clinical characteristics of the previously reported case and our patient: the involvement of the dorsal and caudal parts of the medullary and associated ipsilateral hemiplegia. The present case may support the speculation that the lateral and caudal regions of the medulla may be the anatomical sites responsible for inducing cervical dystonia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cervical dystonia is a focal dystonia characterized by sustained, involuntary contraction of the neck muscles, resulting in abnormal movements and postures of the head [1]. It is known that cervical dystonia is induced by focal organic lesions involving various regions of the brain. Primarily caused by lesions in the cerebrum, including the caudate nucleus, putamen, pallidum, thalamus, frontal cortex, and parietal cortex, lesions in the cerebellum and/or brain stem are also able to cause secondary cervical dystonia [2]. Recently, we encountered a patient who developed cervico-shoulder dystonia following lateral medullary infarction. We present the clinical data of the patient and review cases of other patients with secondary cervical dystonia caused by brain stem lesions.

Case presentation

An 86-year-old Japanese woman was admitted to our hospital with the sudden appearance of weakness in the left upper and lower extremities, numbness of the right upper and lower extremities, and dysarthria. Her family history was unremarkable. Particularly, she had no family history of movement disorders. She had hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia. At age 82, she had developed hemiparesis caused by a lacunar infarction of the left capsulothalamic region, and her neurological symptoms fully improved without sequelae.

On admission, her blood pressure was 202/98 mmHg, but her heartbeat was regular. Her other general status was unremarkable. A neurological examination revealed that she was alert and oriented, without dementia. Her cranial nerves were intact, but her speech was mildly dysarthric. Horner’s sign was not noted. Hemiparesis was assessed according to the Medical Research Council scale and was noted in the upper and lower extremities with manual muscle strength scale scores of 3 and 4 for the upper and lower extremities, respectively. No pathological reflex was noted. Her superficial sensation was disturbed in her upper and lower extremities and body on the right side. Her position sensation was disturbed in her left upper and lower extremities. Her vibration sensation was intact. Her National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale assessment yielded 3 points.

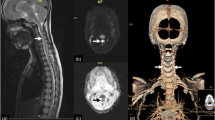

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at admission (day 1) did not reveal ischemic lesions. However, brain MRI performed again at day 2 did reveal an ischemic lesion in the left lateral lower medulla (Figs. 1 and 2). Magnetic resonance angiography showed a decreased left vertebral artery signal (Fig. 3a). Basi-parallel anatomic scanning (BPAS) MRI delineated the outside shape of the left vertebral artery (Fig. 3b), suggesting that the vertebral artery might be obstructed. This was confirmed by 3D computed tomographic angiography.

Magnetic resonance angiography revealing the disappearance of the left vertebral artery (left panel). Basi-parallel anatomic scanning magnetic resonance imaging delineates the outside shape of the left vertebral artery, indicating that the vertebral artery was not hypoplastic but obstructed (right panel)

A few days after admission, the patient experienced sustained pain and a taut sensation, localized in her left neck. Several days afterward, her head was found involuntarily deviated to the right, with tonic contraction of her right sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles (Fig. 4). On occasion, her left shoulder and arm elevated involuntary. We suspected that she had cervico-shoulder dystonia. Within a few weeks, her dystonic symptoms as well as her neck pain gradually improved and disappeared, although she had residual neurological sequelae, such as left hemiparesis (ipsilateral hemiplegia, called Opalski’s syndrome), right hemisuperficial sensory loss, and disturbance of the left position sense.

Discussion

Our patient experienced secondary cervico-shoulder dystonia following acute lateral medullary infarction. In addition, the lateral medullary lesion did not induce Wallenberg syndrome, but it did produce Opalski’s syndrome.

Opalski’s syndrome is a classically known syndrome, a rare variant of lateral medullary syndrome characterized by ipsilateral hemiplegia. Lesions responsible for Opalski’s syndrome are usually located within the sub-bulbar part of the medulla. From an anatomical perspective, it is presumed that the ipsilateral hemiplegia caused is due to the involvement of the lateral corticospinal tract after pyramidal decussation [3]. Also, in our patient, the lesion was localized in the tegmentum of the caudal medulla, potentially disrupting the ipsilateral lateral corticospinal tract (Figs. 1 and 2).

A comprehensive review of the literature has been published regarding cerebellar lesion-induced cervical dystonia [4]. However, no review of the relationship between brain stem lesions and secondary cervical dystonia has been published to date. Therefore, we review the literature on secondary cervical dystonia due to brain stem lesions (Table 1) [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. To the best of our knowledge, between 1979 and 2016, a total of 18 cases with secondary cervical dystonia have been reported, including our patient. The age of onset varies from 15 months to 86 years. The phenotypes of dystonia are heterogeneous, and various head positions can be induced, such as rotation, laterocollis, anterocollis, or retrocollis, with or without shoulder elevation. Of note, of 18 patients, 13 (72%) presented with rotation of the head, 12 (67%) had laterocollis, and 7 (54%) had both rotation and laterocollis. The relationship between the lesion side and the direction of torticollis is 25% ipsilateral and 58.3% contralateral. A single brain stem lesion can be sufficient to induce cervical dystonia because multiple brain stem lesions were observed in only four patients. Various background disorders are responsible for secondary cervical dystonia: cerebrovascular stroke (n = 8 [44.4%], including four infarction cases and four hemorrhage cases), brain tumor (n = 8 [44.4%], including two schwannoma cases and one case each of astrocytoma suspected, meningioma, ependymoma, gangliocytoma, arachnoid cyst, cavernous, and hemangioma), multiple sclerosis (n = 1), and diffuse axonal injury (n = 1). This suggests that stroke and tumor are the most common etiologies. Outcomes are variable, but spontaneous improvement is reported in almost half of the cases. As shown in Table 1, the clinical characteristics of the cases are heterogeneous, so no overt relationship between the lesion location and cervical dystonia seems to exist.

However, of these patients with brain stem lesion-induced cervical dystonia, only one case had a single medullary lesion [10]. It is interesting to note that that case exhibited clinical similarities to our patient: the appearance of cervical dystonia toward the contralateral side following the stroke, which disappeared spontaneously; the dorsal, lateral, and caudal parts of the medulla were involved; and with an association with ipsilateral hemiplegia (Opalski’s syndrome). In both cases, it can be speculated that the lesions affected the afferent fibers of the cerebellum with the lateral corticospinal tract. However, it remains unclear whether this type of cervical dystonia may be induced following interruption of the spinocerebellar tract at the caudal medulla. Further accumulation of similar cases is required to better understand the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying secondary cervical dystonia.

One problem that should be considered is whether malfunctioning of the vestibular system possibly influences the head and/or truncal position in these patients with medullary infarction. Indeed, head leaning and body lateropulsion are known to occasionally be induced by a lateral medullary lesion, wherein the vestibular nucleus is located. However, we suspect that impairment of the vestibular system was not related to the mechanism underlying cervical dystonia in our patient or in the similar previously reported case, because the direction of head leaning was ipsilateral to the medullary lesion [14], whereas the direction of cervical dystonia in our patient was contralateral. In addition, the location of the medullary infarction in our patient was clearly caudal to the level wherein the vestibular nucleus is located.

Conclusions

Although it remains uncertain whether cervical dystonia is more likely to be complicated by Opalski’s syndrome, this type of cervical dystonia might be overlooked in patients with acute stroke, particularly those with hemiparesis. We believe this case report contributes to recognizing the possible relationship between caudal medullary lesions and cervical dystonia, as well as facilitates the accumulation of similar cases for better understanding of secondary dystonia.

Abbreviations

- BPAS:

-

Basi-parallel anatomic scanning

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Jankovic J, Leder S, Warner D, Schwartz K. Cervical dystonia: clinical findings and associated movement disorders. Neurology. 1991;41(7):1088–91.

LeDoux MS, Brady KA. Secondary cervical dystonia associated with structural lesions of the central nervous system. Mov Disord. 2003;18(1):60–9.

Opalski A. A new sub-bulbar syndrome: partial syndrome of the posterior vertebro-spinal artery. Paris Med. 1946;1:214–20.

Usmani N, Bedi GS, Sengun C, et al. Late onset of cervical dystonia in a 39-year-old patient following cerebellar hemorrhage. J Neurol. 2011;258(1):149–51.

Boisen E. Torticollis caused by an infratentorial tumour: three cases. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:306–7.

Plant GT, Kermode AG, du Boulay EP, McDonald WI. Spasmodic torticollis due to a midbrain lesion in a case of multiple sclerosis. Mov Disord. 1989;4(4):359–62.

Krauss JK, Mohadjer M, Braus DF, et al. Dystonia following head trauma: a report of nine patients and review of the literature. Mov Disord. 1992;7(3):263–72.

Caress JB, Nohria V, Fuchs H, Boustany RM. Torticollis acquired in late infancy due to a cerebellar gangliocytoma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;36(1):39–44.

Krauss JK, Seeger W, Jankovic J. Cervical dystonia associated with tumors of the posterior fossa. Mov Disord. 1997;12(3):443–7.

Kajimoto Y, Miwa H, Ueno M, Kondo T. Sensorimotor hemiparesis with secondary cervical dystonia following lateral caudal medullary infarction without signs and symptoms of Wallenberg syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 2004;219(1-2):167–8.

Loher TJ, Krauss JK. Dystonia associated with pontomesencephalic lesions. Mov Disord. 2009;24(2):157–67.

Agrawal A, Cincu R, Joharapurkar SR, et al. Hemorrhage in brain stem cavernoma presenting with torticollis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2009;45(1):49–52.

DeBenedictis CN, Allen JC, Kodsi SR. Brainstem tumor presenting with tearing, photophobia, and torticollis. J AAPOS. 2010;14(4):369–70.

Thömke F, Marx JJ, Iannetti GD, et al. A topodiagnostic investigation on body lateropulsion in medullary infarcts. Neurology. 2005;64:716–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

We received no funding support for this report.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TO and HM were responsible for the study concept and design. TO, TK, YS, and HE acquired data. TO, NH, and HM analyzed and interpreted data. TO and HM drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors declare that ethics approval was not required for this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in- Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogawa, T., Shojima, Y., Kuroki, T. et al. Cervico-shoulder dystonia following lateral medullary infarction: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 12, 34 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1561-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1561-y