Abstract

Background

Ectopic cerebellar tissue located distantly from the normal cerebellum is very rare, and its pathophysiology remains to be elucidated.

Case presentation

We report an extremely rare case of intraosseous ectopic cerebellum detected incidentally at suboccipital craniotomy in a 46-year-old Japanese woman with hemifacial spasm. She had a small bone defect in the occipital bone, which contained a tiny area of soft tissue surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid connecting to the normal subarachnoid space through a dural opening. Histopathology demonstrated cerebellar cortex tissue consisting of molecular and granular cell layers.

Conclusions

This is the first report of glioneuronal ectopia within the skull bone separated from normal brain tissue, and it is important to distinguish this entity from other osteolytic lesions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ectopic cerebellar tissue located distantly from the normal cerebellum is very rare, with 13 previously reported cases in the literature, of which only one was an adult case. This is obviously different from tonsillar herniation with Chiari malformations and its pathogenesis or association with any syndrome remains to be elucidated. This report describes the first known case of ectopic cerebellar tissue in the skull and discusses the differential diagnosis and pathogenesis of ectopic cerebellum.

Case presentation

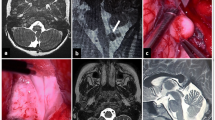

A 46-year-old Japanese woman presented with right hemifacial spasm that had persisted for 2 years, and was admitted to our hospital for microvascular decompression. She had shown no medical abnormality during the perinatal period and had developed normally. Furthermore, she had no history of malignant diseases or severe head injury, or any remarkable family history. Findings of physical and neurological examinations were unremarkable except for right hemifacial spasm with synkinesis. A head computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a small intraosseous defect 6 mm in diameter in the right occipital bone. Magnetic resonance (MR) images obtained using heavily T2-weighted MR cisternography showed an isointense mass 6 mm in diameter outside the right cerebellar hemisphere, corresponding to the bone defect. Around the mass, there was a high-intensity area similar to cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which was continuous with the intracranial subarachnoid space (Fig. 1), indicating that the mass was located within the subarachnoid space.

Our patient underwent a right suboccipital craniotomy to create an opening 3 cm in diameter. After craniotomy, there were several small dural openings, causing some CSF leakage. The outer table of the detached bone was normal while the inner table was partially lacking, creating a tiny cavity filled with fragile reddish tissue (Fig. 2). The tissue which was obviously separated from the cerebellar tissue was resected to be a subject for pathological examination.

A photograph of the bone graft after craniotomy on the dural side (a, b) and findings of light microscopy (c, d). Low-power photomicrograph demonstrating the cerebellar cortex, which shows both the molecular layer and the granular layer (c). Meninges are evident around the tissue. Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification × 40. High-power photomicrograph showing the granular layer (*), molecular layer (**), and white matter (***). Hematoxylin and eosin, original magnification × 200 (d)

After successful microvascular decompression, the wound was closed using the bone graft for cranioplasty. Her postoperative course was uneventful and she was discharged without facial spasms or any neurological complication.

Histopathological examination

The specimen exhibited a fragment of cerebellar tissue with gliosis, as well as necrotic bone and fibrous interstitial tissue. The cerebellar tissue consisted of cerebellar cortex and white matter. The cerebellar cortex clearly exhibited the molecular layer and the granular layer; however, Purkinje cells were depleted, and had been replaced by proliferation of Bergmann glia. The white matter was gliotic, and meninges were evident at the surface of the cerebellum. There were no features indicative of neoplasia.

Discussion

Although some previous reports have referred to cerebellar ectopia, the definition itself has not been consistent. Caudal displacement of the tonsils due to Chiari malformation has been described as a manifestation of cerebellar ectopia in some previous cases [1, 2], including an extreme case of Chiari II malformation with complete caudal displacement of the cerebellum [1]. However, these cases should be referred to as displacement of the cerebellum, and not ectopia [3]. The term “heterotopic cerebellum” or “cerebellar heterotopia” has sometimes been used to indicate ectopic cerebellum. The terms ectopic and heterotopic are not synonymous but have precise definitions; ectopic cells occur outside their organ of origin whereas heterotopic cells are in an aberrant location within their organ of origin [4]. Ectopic cerebellum should be appropriately distinguished from heterotopia, which would include the more frequent focal entity, cerebellar cortical dysplasia.

Ectopic cerebellar tissue is very rare, and only 13 cases have been reported previously to the best of our knowledge (Table 1). Four of these cases were associated with neural tube defects [5,6,7,8] and two cases involved nasopharyngeal teratoma with ectopic cerebellar tissue in the suprasellar region [9, 10]. Six cases were unassociated with any other diseases or malformations. The locations of the ectopic cerebellar tissue included the fourth ventricle, orbit, frontal fossa, posterior fossa, suprasellar region, and sphenoid ridge [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Four of them presented with a mass effect, and one with epilepsy. All of the patients except one were children.

Although the pathogenesis of ectopic glioneuronal masses has not been well understood, two main hypotheses have been classically proposed [16, 18, 19]. One of them is brain herniation or protrusion; that is, herniation of mature tissue from the neuraxis through a pre-existing pial defect [20]. The other is aberrant migration, that is, embryonic neuroepithelial tissue that aberrantly migrates into the subarachnoid space and subsequently develops into mature brain tissue.

It is noteworthy that primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliomatosis can arise from ectopic glial tissue, although this is very rare and often associated with progressive deterioration of clinical status [21,22,23]. A rare case of malignant glioma suspected to have arisen from ectopic glial tissue at the cavernous sinus has also been reported [24]. The possibility of malignant change of ectopic glial tissue is still worthy of consideration, even though intraosseous glioma has not been reported.

An intraosseous osteolytic lesion of the skull, such as that in the presented case, also needs to be distinguished from intraosseous neoplasms, such as meningioma, hemangioma, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, dermoid cyst, multiple myeloma, and malignant lymphoma. Images of such entities should be evaluated carefully focusing on the site, shape, and multiplicity of the lesion, the presence of accompanying soft tissue components, or any extracranial lesions [25].

A recent study presented a case of radiologically proven ectopic cerebellar tissue using diffusion tensor tractography and MR spectroscopy in a newborn [12]. If the tissue is big enough to be assessed by such neuroimaging tools and has connection with cerebellum, it is reasonable to diagnose ectopia with only radiological findings and without histopathological examinations.

Our patient had a tiny area of tissue within the occipital bone in the posterior cranial fossa, which was revealed histopathologically to possess typical cerebellar structure with gliosis. Preoperative radiological evaluation and our intraoperative findings demonstrated that this ectopic mass was surrounded by a normal subarachnoid space. Our observations and histopathological findings suggest that this ectopic cerebellar tissue could have protruded into the occipital bone through a dural defect and detached from cerebellum at an early stage of development, and then degenerated slightly or failed to undergo normal maturation, resulting in loss of Purkinje cells.

Conclusions

We have described the first reported case of intraosseous ectopic cerebellar tissue in an adult woman with facial spasm but without any other neurological disorders. The clinical significance of these lesions should be clarified in future with further accumulation of cases.

Abbreviations

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

References

Kudryk BT, Coleman JM, Murtagh FR, Arrington JA, Silbiger ML. MR imaging of an extreme case of cerebellar ectopia in a patient with Chiari II malformation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1991;12:705–6.

Mohr PD, Strang FA, Sambrook MA, Boddie HG. The clinical and surgical feature in 40 patients with primary cerebellar ectopia (adult Chiari malformation). Q J Med. 1977;46:85–96.

Kesack CD, Mamourian AC. Extracranial cerebellum. CT and MR findings of an unusual variation of the Chiari II malformation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:849–50.

Sarnat HB. Ectopic or heterotopic? An appeal for semantic precision in describing developmental disorders of the nervous system. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;13:178–9.

Call NB, Baylis HI. Cerebellar heterotopia in the orbit. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:717–9.

Chung CJ, Castillo M, Fordham L, Mukherji S, Boydston W, Hudgins R. Spinal intradural cerebellar ectopia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:897–9.

Sarnat HB, deMello DE, Blair JD, Siddiqui SY. Heterotopic growth of dysplastic cerebellum in frontal encephalocele in an infant of a diabetic mother. Can J Neurol Sci. 1982;9:31–5.

Suneson A, Kalimo H. Myelocystocele with cerebellar heterotopia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1979;51:392–6.

Chang AH, Kaufmann WE, Brat DJ. Ectopic cerebellum presenting as a suprasellar mass in infancy: implications for cerebellar development. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2001;4:89–93.

Takhtani D, Melhem ER, Carson BS. A heterotopic cerebellum presenting as a suprasellar mass with associated nasopharyngeal teratoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1119–21.

Billings KJ, Danziger FS. Cerebellar heterotopia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1973;38:218–20.

Gunbey HP, Bilgici MC, Aslan K, Aygün C, Celik H. Ectopic cerebellar tissue of the posterior cranial fossa: diffusion tensor tractography and MR spectroscopy findings. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32:195–8.

Marubayashi T, Matsukado Y. Intracranial extracerebral brain heterotopia. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:470–4.

Matyja E, Grajkowska W, Marchel A, Rysz A, Majkowska-Zwolinska B. Ectopic cerebellum in anterior cranial fossa: Report of a unique case associated with skull congenital malformations and epilepsy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:322–5.

Nagaraj U, Boue DR, Humphrey B, Martin LC. Ectopic cerebellum in the posterior cranial fossa. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42:1391–4.

Okazaki T PK, Sato Y, Y N. A case of asymptomatic suprasellar ectopic cerebellum. Nerv Syst Child. 2004,29:446–9.

Kagotani Y, Takao K, Nomura K, Imai Y, Hashimoto K. Intraorbital cerebellar heterotopia associated with Chiari I malformation. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1996;33:262–5.

Abel TJ, Chowdhary A, Thapa M, Rutledge JC, Gruss J, Manning S, Avellino AM. Ectopic glioneuronal tissue in the middle cranial fossa region. Report of four cases. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;3:188–96.

Nishio SMJ, Barrow DL, Takei YOBM. Intracranial extracerebral glioneuronal heterotopia. Child’s Nerv Syst. 1988;4:244–8.

Cooper IS, Kernohan JW. Heterotopic glial nests in the subarachnoid space; histopathologic characteristics, mode of origin and relation to meningeal gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1951;10:16–29.

Debono B, Derrey S, Rabehenoina C, Proust F, Freger P, Laquerrière A. Primary diffuse multinodular leptomeningeal gliomatosis: case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:273–82. discussion 282.

Dimou J, Tsui A, Maartens NF, King JA. Primary diffuse leptomeningeal gliosarcomatosis with a sphenoid/sellar mass: confirmation of the ectopic glial tissue theory? J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:702–4.

Kobayashi M, Hara K, Nakatsukasa M, Murase I, Toya S. Primary spinal leptomeningeal gliomatosis presenting visual disturbance as the initial symptom: case report. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1996;138:480–1.

Taomoto K, Ohnishi H, Kamada Y, Kuga Y, Kohaya N, Nakashima K, Ichioka T, Tominaga T, Nakamura M, Nakazato Y. A rare case of malignant glioma suspected to have arisen from a cavernous sinus. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2007;24:75–80.

Nakamura H, Wang H, Westesson PL, Hoshikawa M, Takagi M, Nakajima Y. Intraosseous tumors of the skull. A pictorial review. Neuroradiol J. 2012;25:461–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK, MK, and TF performed the surgery and clinical evaluation of the patient. KI was the pathologist involved in the diagnosis of this case. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawashima, M., Kobayashi, M., Ishizawa, K. et al. Ectopic cerebellar tissue in the occipital bone: a case report. J Med Case Reports 11, 231 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1394-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-017-1394-0