Abstract

The common house spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum, belonging to the Chelicerata in the phylum Arthropoda, has emerged as an experimental system for studying mechanisms of development from an evolutionary standpoint. In this article, we review the distinct characteristics of P. tepidariorum, the major research questions relevant to this organism, and the available key methods and resources. P. tepidariorum has a relatively short lifecycle and, once mated, periodically lays eggs. The morphogenetic field of the P. tepidariorum embryo is cellular from an early stage and exhibits stepwise symmetry-breaking events and stripe-forming processes that are associated with body axes formation and segmentation, respectively, before reaching the arthropod phylotypic stage. Self-regulatory capabilities of the embryonic field are a prominent feature in P. tepidariorum. The mechanisms and logic underlying the evolvability of heritable patterning systems at the phylum level could be one of the major avenues of research investigated using this animal. The sequenced genome reveals whole genome duplication (WGD) within chelicerates, which offers an invertebrate platform for investigating the potential roles of WGD in animal diversification and evolution. The development and evolution of lineage-specific organs, including the book lungs and the union of spinnerets and silk glands, are attractive subjects of study. Studies using P. tepidariorum can benefit from the use of parental RNA interference, microinjection applications (including cell labeling and embryonic RNA interference), multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization, and laser ablation as well as rich genomic and transcriptomic resources. These techniques enable functional gene discoveries and the uncovering of cellular and molecular insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Natural habitat and lifecycle

Parasteatoda tepidariorum (syn. Achaearanea tepidariorum), also referred to as the common house spider, has adapted to environments profoundly affected by human activities and is widespread throughout the world. For example, juveniles and adults are found upon their webs in the corners of building surfaces (Fig. 1). Juveniles undergo several molts before becoming adults and displaying sexual dimorphism (Fig. 2). Adult males acquire a slim body type and demonstrate active walking, whereas adult females retain a characteristically large abdomen and stay on the web nest. Once mated, females repeat cycles of egg production and laying (without the need for additional mating). Each cycle takes about 4–6 days in laboratory conditions, and involves the production of an egg sac containing approximately 200–300 eggs. After laying, the eggs hatch in 7 days at 25 °C, and, subsequently, juveniles take approximately 2–3 months to become sexually mature adults (Fig. 2). Of note, P. tepidariorum diapauses in short-day conditions [1].

Parasteatoda tepidariorum adult female in the wild. a Concrete revetment is a typical site for collecting P. tepidariorum adults and juveniles. b There is an adult female settled on the web in a corner of a concrete revetment (closeup of the boxed region in a. c Closeup of the wild female with an egg sac (the boxed region in b)

Lab culture

Laboratory colonies of P. tepidariorum can be maintained at 25 °C in long-day conditions (16 h light, 8 h dark) over many (i.e., > 30) generations after capture from the wild. Juveniles and adults are fed twice a week with live Drosophila melanogaster, and adult females are additionally fed with live crickets after being transferred to containers for mating and egg laying. Each mated female produces up to ~ 10 egg sacs. When maintaining juveniles hatched from a single egg sac in a 9-cm petri dish with cut cotton, typically only a few will survive due to cannibalism and some of these are then individually transferred into separate Drosophila culture tubes where they are reared to adulthood. Videos that illustrate how to culture P. tepidariorum in a laboratory setting are available on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/user/BRHjapan/).

The egg surface is opaque in open air but becomes transparent—without affecting embryonic development—when the eggs are placed in oil (e.g., halocarbon oil 700). This characteristic, combined with the simultaneous oviposition of hundreds of eggs, is helpful for monitoring embryonic development. The development and staging systems for the P. tepidariorum embryo have been described [2,3,4,5] with some variation in the defined transition points of certain stages. Eggs in oil, however, fail to hatch and no solutions to remedy this issue have been reported.

Major interests and research questions

Phylogenetic position

The spider P. tepidariorum belongs to Chelicerata, one of the four major superclasses in the phylum Arthropoda. This group has been suggested to be phylogenetically most distant from the Hexapoda (which includes D. melanogaster) among extant arthropods [6, 7]. Thus, for understanding the ancestral modes and/or mechanisms of arthropod development, P. tepidariorum is a reasonable organism to select for comparative studies.

Axis formation and segmentation

Parasteatoda tepidariorum eggs are spherical in shape. During the initial developmental stages (i.e., stages 1 and 2), no morphological landmarks exist to indicate future body axes. The first symmetry-breaking event leads to the formation of a radially symmetric germ disc, and the second symmetry-breaking event leads to the formation of a bilaterally symmetric germ band (Fig. 2). These symmetry-breaking events are observed as directional collective cell movements or behaviors. Although it is not known whether the direction of the body axes has been determined in advance, a “stochastic” model has been proposed for the emergence of the second axis based on experimental data [8].

The number of segmental units increases while the anterior–posterior axis is growing in the developing Parasteatoda embryo. This segmentation mode contrasts with that of Drosophila, but is widely observed in arthropods, including many non-Drosophila insects. The cellular and molecular events at the posterior terminal region, as well as the presumptive head region of the forming or elongating germ band, in Parasteatoda attract researchers who seek to understand the evolution of arthropod segmentation [9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

The nature of the morphogenetic field of the early P. tepidariorum embryo, in which the embryonic axes and segments are patterned, sharply contrasts with that of the blastoderm embryo of D. melanogaster. The Parasteatoda embryonic field is cellular at the 16-nucleus stage or perhaps even earlier [16]. In contrast, the field of Drosophila consists of a syncytium until the nuclei number increases to approximately 6000. This difference likely correlates with differences in the molecular systems patterning the major embryonic axes [8,9,10, 17,18,19].

Periodic stripe patterns associated with the body segments appear to be generated through different mechanisms in the terminal and the middle regions of the Parasteatoda embryo. In the terminal regions, unlike Drosophila, synchronized oscillation and stripe-splitting occur in concert with axis growth [11,12,13]. The patterning of the middle region, however, is more Drosophila-like, with the simultaneous appearance of segmental stripes. The presence of variability in the insect and spider embryonic fields, in recognition of conserved segmented germ bands (the arthropod phylotypic stage; Fig. 2), fits within the developmental hourglass model [20, 21]. The evolvability of heritable patterning systems associated with arthropod axis specification and segmentation could be the subject of future studies involving P. tepidariorum.

Self-regulation

Another intriguing embryological phenomenon occurring in P. tepidariorum is revealed by laser ablation of part of the germ disc, which fragments the field and results in a partial duplication of the body axes [22]. Similar experiments were originally conducted by Holm more than 70 years ago using a different spider species [23]. The results of these experiments suggested the existence of self-regulatory capabilities of fragmented embryonic fields in forming whole-body patterns. There have been few experimental systems, at least in arthropods, used for investigating these types of capabilities in embryonic fields [24,25,26]. Similar embryological phenomena have been reported in some vertebrate models [27]. P. tepidariorum offers an experimental system to study mechanisms of self-regulation.

Genome evolution

The sequenced P. tepidariorum genome reveals a whole genome duplication (WGD) event that possibly occurred in a common ancestor of spiders and scorpions following their phylogenetic separation from the other chelicerate lineages that evolved into mites, ticks, and horseshoe crabs [28]. In addition to duplicated Hox gene clusters, many other developmental genes are found in multiple copies in Parasteatoda [29, 30]. This offers a platform for investigating the effects of WGD on the evolution of gene composition, regulation, and interaction, as well as the potential roles of WGD in animal diversification and evolution.

Lineage-specific traits

The book lungs are a unique respiratory system shared by spiders, scorpions, and their kin. The cheliceral venom gland and the union of spinnerets and silk glands are spider-specific novelties. The development and evolution of these organs, which are associated with the spiders’ terrestrial lifestyles and biology, are intriguing topics to study in Parasteatoda [31,32,33,34].

Behaviors

Juvenile and adult spiders exhibit complex behaviors, associated with nest-building, predation, courtship, egg laying, and caring. Despite the importance of this behavioral complexity and diversity from the viewpoint of evolutionary ecology, the development of neural structures and networks underlying such behaviors has been little studied at the cellular and molecular levels. The P. tepidariorum experimental system could provide interesting insights in this research area.

Experimental approaches

pRNAi

A key method for genetic manipulation in Parasteatoda is parental RNA interference (pRNAi), which is achieved by repeated injections of dsRNA targeting a specific gene into the abdomen of an adult female. Egg sacs produced after 1 week contain hundreds of embryos in which the expression of the target gene is suppressed [17] (Fig. 3a). The specificity of the RNAi effect can be validated by independently obtaining the same phenotypes via the administration of different dsRNAs prepared from non-overlapping regions of the target gene. A variety of phenotypes have been obtained by pRNAi, specific to the target genes, suggesting that functional genetic screens could be implemented to dissect the phenomena of interest. However, the pRNAi approach can be limited if the target genes have critical functions prior to the stages of interest. Hundreds of pRNAi-treated embryos simultaneously developing in an egg sac can be highly useful for conducting downstream experiments, including microarrays and RNA sequencing [11]. Effective combinations of genome-wide gene expression analyses and pRNAi-mediated gene knockdowns may facilitate discoveries of functional genes without relying on knowledge from other organisms.

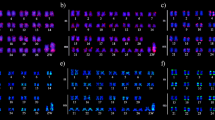

Key methods that have been applied to P. tepidariorum. a Schematic representation of the typical procedure and timeline of pRNAi-mediated gene knockdown in P. tepidariorum. dsRNA for the target gene is repeatedly injected into the abdomen of a mated female. The RNAi effect typically appears in egg sacs that are produced more than 1 week after the first dsRNA injection. b The setup for microinjection and three examples of microinjection applications, depending on the materials injected. Bleached eggs are attached on a glass slide using double-sticky tape, covered with halocarbon oil, and then injected. 16- to 128-cell stages constitute the period when the injection can be performed relatively easily. For eRNAi, dsRNA for Pt-orthodenticle (Pt-otd) was co-injected with FITC-dextran, visualized in red in the fixed sample. The embryo was also stained for Pt-hh transcript, demonstrating that Pt-otd positively regulates Pt-hh expression in the anterior region of the nascent germ band [11]. The images showing histone-tdEosFP expression and the eRNAi are adapted and modified from Hemmi et al. [13] (CC BY 4.0) and Kanayama et al. [11] (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0), respectively. c Flat preparation of a germ band stained for Pt-hh (green) and Pt-noto1 (red) transcripts by multicolor FISH and counter-stained for DNA (blue). This image is adapted and modified from Hemmi et al. [13] (CC BY 4.0). d The infrared laser module used for laser ablation (left) and an example of a laser-irradiated embryo (right). The XYClone laser module is integrated with a 20× objective lens (Hamilton Thorne). In the embryo shown, which had been laser-irradiated 7 h before, dead cells derived from the irradiated region were apparent (asterisks). The left (L) and right (R) embryonic fields were developing into partially separate germ bands. The image of the embryo is adapted and modified from Oda et al. [22] (CC BY 4.0). Scale bars: 50 µm

Microinjection and eRNAi

Microinjection of single cells in early P. tepidariorum embryos has been applied for cell labeling, exogenous protein expression and embryonic RNAi within cell clones (eRNAi) [11, 16] (Fig. 3b). Cell labeling can be used to determine cell fate as well as gene expression dynamics relative to marked cell clones. This can be achieved by microinjection of synthetic mRNA coding for fluorescent marker proteins to track cell divisions and movements by means of live imaging [11, 13, 35]. Freshly laid eggs, within a few hours from laying, are too fragile to be injected, not allowing wider regions of the embryo to be labeled at early stages.

Microinjection of dsRNA in individual cells can also be used to knockdown gene function within cell clones. The gene silencing effect appears to be limited to the injected cell clones, although non-autonomous phenotypic effects might be observed outside of the clones [11]. This clonal eRNAi approach is useful for investigating the roles of genes within small groups of cells, overcoming the deleterious effects of some global pRNAi-mediated gene knockdowns.

Multicolor FISH

Multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) has enabled the simultaneous visualization and quantification of the expression of up to four different gene transcripts in P. tepidariorum embryos [36] (Fig. 3c). This technique could be combined with cell labeling and eRNAi. The use of multicolor FISH can contribute not only to more precise functional analyses, but also to the acquisition of quantitative data for theoretical and mathematical analyses [13].

Laser ablation

Laser ablation, using a high power, Class 1, 1460 nm infrared laser integrated with a 20× objective lens, has been applied to kill cells in specific regions of the embryonic field without damaging other regions of the embryo [22] (Fig. 3d). This approach may help identify the mechanisms of regulative development in Parasteatoda embryos.

Limitations

To our knowledge, no methods for transgenesis or genome editing have been reported in P. tepidariorum, due to difficulties in microinjecting early embryos and limited evidence on the developmental origin of germ cells [37]. Rescue of hatching animals from oil, as well as cannibalism, may be additional hurdles to overcome. Limited availability of antibodies and the lack of spider-derived cell lines are also limiting in this system.

Research community and resources

There are more than 10 research groups currently using P. tepidariorum for evo-devo studies worldwide. They have organized a forum called “SpiderWeb” (http://www.spiderweb.uni-goettingen.de) to share information, opinions and to find opportunities for collaboration.

The genome of a P. tepidariorum Göettingen isolate has been sequenced [28] and included in the NCBI’s reference sequence (RefSeq) database (see Table 1). The degree of sequence variation between the genomes of the Göettingen and Osaka/Kyoto isolates is limited [38], thereby allowing most of the Parasteatoda community to effectively use the reference genome. There are several sources of gene models and de novo transcriptome assemblies available [28, 38,39,40] (Table 1). There are several database websites available for P. tepidariorum users (Table 1).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- BCM-HGSC:

-

Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center

- BRH:

-

Biohistory Research Hall

- DDBJ:

-

DNA Data Bank of Japan

- dsRNA:

-

Double-stranded RNA

- eRNAi:

-

Embryonic RNA interference

- EST:

-

Expression sequence tag

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NGS:

-

Next generation sequencing

- pRNAi:

-

Parental RNA interference

- RefSeq:

-

Reference sequence

- RNAi:

-

RNA interference

- RNA-Seq:

-

RNA sequencing

- URL:

-

Uniform resource locator

- WGD:

-

Whole genome duplication

References

Tanaka K. Photoperiodic control of diapause and climatic adaptation of the house spider, Achaearanea tepidariorum (Araneae, Theridiidae). Func Ecol. 1992;6:545–52.

Montgomery TJ. The development of Theridium, an Aranead, up to the stage of reversion. J Morphol. 1909;20:297–352.

Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Early patterning of the spider embryo: a cluster of mesenchymal cells at the cumulus produces Dpp signals received by germ disc epithelial cells. Development. 2003;130:1735–47.

Yamazaki K, Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Expression patterns of a twist-related gene in embryos of the spider Achaearanea tepidariorum reveal divergent aspects of mesoderm development in the fly and spider. Zoolog Sci. 2005;22:177–85.

Mittmann B, Wolff C. Embryonic development and staging of the cobweb spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. L. Koch, 1841 (syn.: Achaearanea tepidariorum; Araneomorphae; Theridiidae). Dev Genes Evol. 2012;222:189–216.

Rota-Stabelli O, Daley AC, Pisani D. Molecular timetrees reveal a Cambrian colonization of land and a new scenario for ecdysozoan evolution. Curr Biol. 2013;23:392–8.

Ballesteros JA, Sharma PP. A Critical appraisal of the placement of Xiphosura (Chelicerata) with account of known sources of phylogenetic error. Syst Biol. 2019;68:896–917.

Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Cell migration that orients the dorsoventral axis is coordinated with anteroposterior patterning mediated by Hedgehog signaling in the early spider embryo. Development. 2010;137:1263–73.

Oda H, Nishimura O, Hirao Y, Tarui H, Agata K, Akiyama-Oda Y. Progressive activation of Delta-Notch signaling from around the blastopore is required to set up a functional caudal lobe in the spider Achaearanea tepidariorum. Development. 2007;134:2195–205.

McGregor AP, Pechmann M, Schwager EE, Feitosa NM, Kruck S, Aranda M, Damen WGM. Wnt8 is required for growth-zone establishment and development of opisthosomal segments in a spider. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1619–23.

Kanayama M, Akiyama-Oda Y, Nishimura O, Tarui H, Agata K, Oda H. Travelling and splitting of a wave of hedgehog expression involved in spider-head segmentation. Nat Commun. 2011;2:500.

Schönauer A, Paese CL, Hilbrant M, Leite DJ, Schwager EE, Feitosa NM, Eibner C, Damen WG, McGregor AP. The Wnt and Delta-Notch signalling pathways interact to direct pair-rule gene expression via caudal during segment addition in the spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. Development. 2016;143:2455–63.

Hemmi N, Akiyama-Oda Y, Fujimoto K, Oda H. A quantitative study of the diversity of stripe-forming processes in an arthropod cell-based field undergoing axis formation and growth. Dev Biol. 2018;437:84–104.

Chipman AD, Edgecombe GD. Developing an integrated understanding of the evolution of arthropod segmentation using fossils and evo-devo. Proc Biol Sci. 2019;286:20191881.

Clark E, Peel AD, Akam M. Arthropod segmentation. Development. 2019;146:dev170480. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.170480.

Kanayama M, Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Early embryonic development in the spider Achaearanea tepidariorum: microinjection verifies that cellularization is complete before the blastoderm stage. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010;39:436–45.

Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Axis specification in the spider embryo: dpp is required for radial-to-axial symmetry transformation and sog for ventral patterning. Development. 2006;133:2347–57.

Wieschaus E. Positional information and cell fate determination in the early Drosophila embryo. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2016;117:567–79.

Rahimi N, Averbukh I, Carmon S, Schejter ED, Barkai N, Shilo BZ. Dynamics of Spaetzle morphogen shuttling in the Drosophila embryo shapes gastrulation patterning. Development. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.181487.

Peel AD, Chipman AD, Akam M. Arthropod segmentation: beyond the Drosophila paradigm. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:905–16.

Irie N, Kuratani S. The developmental hourglass model: a predictor of the basic body plan? Development. 2014;141:4649–55.

Oda H, Iwasaki-Yokozawa S, Usui T, Akiyama-Oda Y. Experimental duplication of bilaterian body axes in spider embryos: Holm’s organizer and self-regulation of embryonic fields. Dev Genes Evol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00427-019-00631-x.

Holm A. Experimentelle Untersuchungen über die Entwicklung und Entwicklungsphysiologie des Spinnenembryos. Zool BiDr Uppsala. 1952;29:293–424.

Sander K. Pattern formation in longitudinal halves of leaf hopper eggs (Homoptera) and some remarks on the definition of “Embryonic regulation”. Wilhelm Roux Arch Entwickl Mech Org. 1971;167:336–52.

Sekiguchi K, Yamamichi Y, Seshimo H, Sugita H, Itow T. Chapter VI. Developmental biology. In: Sekiguchi K, editor. Biology of horseshoe crabs. Tokyo: Seisaku Douzin Co., Ltd; 1999. p. 123–236.

Sachs L, Chen YT, Drechsler A, Lynch JA, Panfilio KA, Lässig M, Berg J, Roth S. Dynamic BMP signaling polarized by Toll patterns the dorsoventral axis in a hemimetabolous insect. elife. 2015;4:e05502.

Moriyama Y, De Robertis EM. Embryonic regeneration by relocalization of the Spemann organizer during twinning in Xenopus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:E4815–22.

Schwager EE, Sharma PP, Clarke T, Leite DJ, Wierschin T, Pechmann M, Akiyama-Oda Y, Esposito L, Bechsgaard J, Bilde T, Buffry AD, Chao H, Dinh H, Doddapaneni H, Dugan S, Eibner C, Extavour CG, Funch P, Garb J, Gonzalez LB, Gonzalez VL, Griffiths-Jones S, Han Y, Hayashi C, Hilbrant M, Hughes DST, Janssen R, Lee SL, Maeso I, Murali SC, Muzny DM, Nunes da Fonseca R, Paese CLB, Qu J, Ronshaugen M, Schomburg C, Schönauer A, Stollewerk A, Torres-Oliva M, Turetzek N, Vanthournout B, Werren JH, Wolff C, Worley KC, Bucher G, Gibbs RA, Coddington J, Oda H, Stanke M, Ayoub NA, Prpic NM, Flot JF, Posnien N, Richards S, McGregor AP. The house spider genome reveals an ancient whole-genome duplication during arachnid evolution. BMC Biol. 2017;15:62.

Leite DJ, Ninova M, Hilbrant M, Arif S, Griffiths-Jones S, Ronshaugen M, McGregor AP. Pervasive microRNA duplication in chelicerates: insights from the embryonic microRNA repertoire of the spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:2133–44.

Leite DJ, Baudouin-Gonzalez L, Iwasaki-Yokozawa S, Lozano-Fernandez J, Turetzek N, Akiyama-Oda Y, Prpic NM, Pisani D, Oda H, Sharma PP, McGregor AP. Homeobox gene duplication and divergence in arachnids. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:2240–53.

Pechmann M, Khadjeh S, Sprenger F, Prpic NM. Patterning mechanisms and morphological diversity of spider appendages and their importance for spider evolution. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2010;39:453–67.

Clarke TH, Garb JE, Hayashi CY, Arensburger P, Ayoub NA. Spider transcriptomes identify ancient large-scale gene duplication event potentially important in silk gland evolution. Genome Biol Evol. 2015;7:1856–70.

Farley RD. Book lung development in embryos of the cobweb spider, Parasteatoda tepidariorum C. L. Koch, 1841 (Araneomorphae, Theridiidae). Arthropod Struct Dev. 2016;45:562–84.

Garb JE, Sharma PP, Ayoub NA. Recent progress and prospects for advancing arachnid genomics. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2018;25:51–7.

Pechmann M, Benton MA, Kenny NJ, Posnien N, Roth S. A novel role for Ets4 in axis specification and cell migration in the spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. Elife. 2017;6:e27590.

Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Multi-color FISH facilitates analysis of cell-type diversification and developmental gene regulation in the Parasteatoda spider embryo. Dev Growth Differ. 2016;58:215–24.

Schwager EE, Meng Y, Extavour CG. vasa and piwi are required for mitotic integrity in early embryogenesis in the spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. Dev Biol. 2015;402:276–90.

Sasaki M, Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Evolutionary origin of type IV classical cadherins in arthropods. BMC Evol Biol. 2017;17:142.

Posnien N, Zeng V, Schwager EE, Pechmann M, Hilbrant M, Keefe JD, Damen WG, Prpic NM, McGregor AP, Extavour CG. A comprehensive reference transcriptome resource for the common house spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e104885.

Kono N, Nakamura H, Ito Y, Tomita M, Arakawa K. Evaluation of the impact of RNA preservation methods of spiders for de novo transcriptome assembly. Mol Ecol Resour. 2016;16:662–72.

Iwasaki-Yokozawa S, Akiyama-Oda Y, Oda H. Genome-scale embryonic developmental profile of gene expression in the common house spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. Data Brief. 2018;19:865–7.

Zeng V, Extavour CG. ASGARD: an open-access database of annotated transcriptomes for emerging model arthropod species. Database. 2012;2012:bas048.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kouichi Sano and Keiko Nakamura for support and encouragement and other members of the JT Biohistory Research Hall for discussions.

Funding

Research in the authors’ laboratory was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) awarded to HO (15K07139) and YA (26440130, 17K07418).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HO prepared all figures. HO and YA wrote the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Oda, H., Akiyama-Oda, Y. The common house spider Parasteatoda tepidariorum. EvoDevo 11, 6 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-020-00152-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-020-00152-z