Abstract

Background

Axon guidance receptors of the Roundabout (Robo) family regulate a number of axon guidance outcomes in bilaterian animals in addition to their canonical role in Slit-dependent midline repulsion. In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, three Robo paralogs (Robo1, Robo2, and Robo3) each have specialized roles in regulating midline crossing and the formation of longitudinal axon pathways in the embryonic ventral nerve cord. The number of robo genes differs in other insects, and it is unknown whether the roles and/or signaling mechanisms of Drosophila Robos are shared in other insect species. To directly compare the axon guidance activities of Robo receptors in Drosophila and the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum, I have used a CRISPR/Cas9-based approach to replace Drosophila robo3 with Tribolium robo2/3.

Results

I show that when expressed from the robo3 locus in Drosophila embryos, Tribolium Robo2/3 (TcRobo2/3) protein is properly translated and localized to axons, where it reproduces the normal expression pattern of Drosophila Robo3. In embryos expressing TcRobo2/3 in place of robo3, two distinct subsets of longitudinal axons are guided properly to their normal positions in the intermediate neuropile, indicating that TcRobo2/3 can promote Robo3-dependent axon guidance decisions in developing Drosophila neurons.

Conclusions

These observations suggest that the mechanism by which Drosophila Robo3 promotes longitudinal pathway formation is evolutionarily conserved in Tribolium, where it is performed by TcRobo2/3. The CRISPR/Cas9-based gene replacement approach described here can be applied to comparative evolutionary developmental studies of other Drosophila genes and their orthologs in other species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Three-dimensional architecture of the insect ventral nerve cord

During development of the nervous system, neural circuits form as axons and dendrites follow directional cues which guide them to specific regions of the central nervous system (CNS), where local contact-dependent cues promote the formation of synaptic connections. In the insect ventral nerve cord, a stereotypical three-dimensional arrangement of axons and dendrites forms within each segmentally repeated neuromere [1, 2]. In the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, where the underlying genetics has been best studied, the medial–lateral and dorsal–ventral position of dendrites, axon terminals, and longitudinal axon pathways within each neuromere is specified by a combination of extracellular guidance cues including Slit and semaphorin ligands, and their neuronal receptors of the Roundabout (Robo) and Plexin families, respectively [3,4,5].

Robo receptors regulate medial–lateral position of axon pathways in Drosophila

In Drosophila, the secreted Slit ligand and its Robo receptors regulate midline crossing of axons in the developing embryonic CNS. In addition, two of the three Robo family members in Drosophila (Robo2 and Robo3) specify the medial–lateral position of longitudinal axon pathways. The functional specialization of the three Drosophila Robos depends on both their differential expression in distinct neuronal subsets and distinct activities of the receptors themselves [6,7,8,9]. Previous gene replacement experiments using a knock-in-based approach demonstrated that exons 2-12 of the Drosophila robo3 gene, along with all of the intervening introns, can be replaced with a non-native cDNA encoding robo3 without any detectable changes to its expression pattern or function [8]. Equivalent experiments replacing robo3 with robo1 or robo2 cDNAs further demonstrated that each of these paralogs can fully substitute for robo3 to promote axon pathway formation in intermediate regions of the neuropile in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. In contrast, neither robo1 nor robo3 can rescue robo2-dependent formation of lateral pathways, suggesting that unique structural features of Robo2 specify this role [8]. Although it has been proposed that Drosophila Robo receptors regulate lateral position in response to a gradient of Slit originating at the CNS midline, the precise mechanism(s) underlying this activity have not been fully characterized [10].

Divergent genetic programs in Drosophila and Tribolium

While robo2 and robo3 have distinct expression patterns and axon guidance roles in Drosophila, these two genes are a product of a recent gene duplication and do not exist as separate genes outside of dipteran insects. Instead, most insect groups have retained an ancestral robo2/3 gene [11, 12]. In the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum, this gene (TcRobo2/3) appears to combine the activities of Drosophila robo2 and robo3 and is required for the formation of both intermediate and lateral axon pathways [11]. The TcRobo2/3 protein exhibits the characteristic ectodomain structure common to most Robo receptors, combining five immunoglobulin-like domains with three fibronectin type III repeats (Fn) within its extracellular portion. TcRobo2/3 shares a high degree of sequence identity with Drosophila Robo2 and Robo3 throughout its extracellular portion, with the highest degree of sequence conservation in the Ig domains, especially the Slit-binding Ig1 domain (Fig. 1) [11]. Sequences within the cytoplasmic domain are less well conserved, and this portion of the protein is significantly shorter in TcRobo2/3 than in Drosophila Robo3 (206 aa versus 452 aa, respectively). Despite this size difference, the two conserved cytoplasmic (CC) motifs present in Drosophila Robo3 are also present in TcRobo2/3. These two motifs, named CC0 and CC1, are conserved in most Robo family members, including Drosophila Robo1, Robo2, and Robo3, as well as Robo1 and Robo2 in vertebrates [13].

Sequence comparison of Drosophila Robo3 and Tribolium Robo2/3. a Schematic comparison of the two receptors showing conserved domain structure and percent identity between individual ectodomain elements. The highest degree of sequence conservation occurs within the Slit-binding Ig1 domain (70% identity). While both proteins share the evolutionarily conserved CC0 and CC1 motifs, the TcRobo2/3 cytodomain (206 aa) is less than half the length of the Robo3 cytodomain (452 aa). b Protein sequence alignment. Structural features are indicated below the sequence. Fn domains have been re-annotated relative to Evans and Bashaw [11] based on revised predictions of beta strand locations. Identical residues are shaded black; similar residues are shaded gray. Ig immunoglobulin-like domain, Fn fibronectin type III repeat, Tm transmembrane helix, CC conserved cytoplasmic motif

CRISPR/Cas9-based trans-species gene replacement

We have previously hypothesized that the ancestor of robo2 and robo3 was required for both intermediate and lateral pathway formation, and that this dual activity is retained by the robo2/3 gene in most insect species (including Tribolium), while the activities of Drosophila robo2 and robo3 have diverged through subfunctionalization after gene duplication [10, 11]. A prediction of this model is that TcRobo2/3 should be able to substitute for both Drosophila robo3 and robo2 to promote intermediate and lateral pathway formation, respectively. Here, I test this prediction by replacing the robo3 gene in Drosophila with the robo2/3 gene from Tribolium via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene replacement. I find that when expressed from the robo3 locus, TcRobo2/3 protein reproduces the endogenous Robo3 expression pattern in the Drosophila embryonic CNS, including proper localization to neuronal axons and distribution on longitudinal axon pathways within intermediate and lateral regions of the neuropile. Further, TcRobo2/3 is able to substitute for robo3 to direct two distinct subsets of longitudinal axons to intermediate regions of the neuropile. These results suggest that Drosophila robo3 and Tribolium robo2/3 regulate axon pathway formation through an evolutionarily conserved mechanism and demonstrate the utility of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene replacement for comparative studies in evolutionary developmental biology.

Methods

Molecular biology

Construction of robo3TcRobo2/3 donor plasmid

The initial robo3 donor construct was assembled from four PCR fragments via Gibson assembly (New England Biolabs E2611). The four fragments were derived from pBluescript (plasmid backbone; primer pair 417–418), the wild-type robo3 genomic locus (5′ and 3′ homology regions; primer pairs 501–502 and 505–506), and the robo3 cDNA (robo3 coding region; primer pair 503–504). This initial donor construct contained an untagged robo3 cDNA flanked by BglII sites. To make the HA-tagged robo3 TcRobo2/3 donor, the robo3 coding sequence was excised with BglII and a 4xHA sequence flanked by BamHI (upstream) and BglII (downstream) sites was cloned into the BglII site, thus retaining a single BglII cloning site immediately downstream of the 4xHA tag. The TcRobo2/3 coding sequence was amplified by PCR using primers 279 and 280, then digested with BglII, and cloned into the 4× HA-containing donor backbone. The entire donor region including TcRobo2/3 coding sequence and robo3 flanking regions was sequenced prior to injection.

Construction of robo3 gRNA plasmid

robo3 gRNA sequences were cloned into the tandem expression vector pCFD4 [14] via PCR using primers 507 and 508, followed by Gibson assembly using the PCR product and BbsI-digested pCFD4 backbone. In both cases, an additional G nucleotide was added to the 5′ end of the gRNA target sequence to facilitate transcription from the U6-1 and U6-3 promoters.

Genetics

Drosophila strains

The following Drosophila strains, transgenes, and mutant alleles were used: Canton-S (wild type), robo3 1 [7], robo3 robo3 [8], robo3 TcRobo2/3 (this study), P{sema2b-TauMyc} [7], w 1118 ; sna Sco /CyO,P{en1}wg en11 (“Sco/CyOwg”). All crosses were carried out at 25 °C.

Generation and recovery of CRISPR-modified alleles

The robo3 gRNA and robo3 TcRobo2/3 homologous donor plasmids were coinjected into nos-Cas9.P embryos [14] by BestGene Inc. (Chino Hills, CA). Injected individuals (G0) were crossed as adults to Sco/CyOwg. Founders (G0 flies producing F1 progeny carrying modified robo3 alleles) were identified by testing two pools of three F1 females per G0 cross by genomic PCR with primers 229 and 280, which produce a 0.8-kb product only when TcRobo2/3 sequences are present. From each identified founder, 5–10 F1 males were then crossed individually to Sco/CyOwg virgin females. After three days, the F1 males were removed from the crosses and tested by PCR with primers 229 and 280 to determine whether they carried the modified allele. F2 flies from positive F1 crosses were used to generate balanced stocks, and the modified alleles were fully sequenced by amplifying the entire modified locus (approx. 6 kb) from genomic DNA using primers 589 and 590, then sequencing the PCR product after cloning via CloneJET PCR cloning kit (Thermo Scientific). Details of G0 survival, fertility, and modified allele transmission rates are provided in Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry

Drosophila embryo collection, fixation, and antibody staining were carried out as previously described [15]. The following antibodies were used: FITC-conjugated goat anti-HRP (Jackson ImmunoResearch #123-095-021, 1:100), Alexa 647-conjugated goat anti-HRP (Jackson #123-605-021, 1:100), mouse anti-Fasciclin II (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DSHB] #1D4, 1:100), mouse anti-βgal (DSHB #40-1a, 1:150), mouse anti-Robo3 (DSHB #15H2, 1:100), mouse anti-HA (Covance #MMS-101P-500, 1:1000), rabbit anti-c-Myc (Sigma-Aldrich #C3956, 1:500), Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Jackson #115-165-003, 1:1000), Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Jackson #111-545-003, 1:500). Embryos were genotyped using balancer chromosomes carrying lacZ markers. Ventral nerve cords from embryos of the desired genotype and developmental stage were dissected and mounted in 70% glycerol/PBS. Fluorescent confocal stacks were collected using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope and processed by Fiji/ImageJ [16] and Adobe Photoshop software.

Results

CRISPR/Cas9-based gene replacement of Drosophila robo3

To test whether Tribolium Robo2/3 can substitute for Drosophila robo3 to promote axon guidance outcomes in the Drosophila embryonic CNS, I used a CRISPR/Cas9-based approach to replace the robo3 gene with TcRobo2/3. Two guide RNAs (gRNAs) targeting exons 2 and 12 were combined with a homologous donor plasmid containing 1-kb flanking regions to induce homology-directed repair, replacing robo3 exons 2-12 with an HA-tagged TcRobo2/3 cDNA (Fig. 2). Briefly, a plasmid expressing both robo3 gRNAs (pCFD4) [14] was injected along with the robo3 TcRobo2/3 donor plasmid into Drosophila embryos expressing Cas9 under the control of the germline-specific nanos promoter [14], and F1 progeny produced from the injected flies were screened by PCR for the presence of TcRobo2/3 sequences. Additional PCR screening and DNA sequencing were used to identify correctly modified robo3 TcRobo2/3 loci among the lines recovered from the positive F1 flies. Further details are provided in Methods and Table 1.

CRISPR-based gene replacement of robo3. a Schematic of the robo3 gene showing intron/exon structure and location of gRNA target sites, robo3 TcRobo2/3 homologous donor plasmid, and the final modified robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele. Endogenous robo3 coding exons are shown as purple boxes; 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions are shown as light gray boxes. The start of transcription is indicated by the bent arrow. Introns and exons are shown to scale, with the exception of the first intron, from which approximately 13 kb has been omitted. Red arrows indicate the location of upstream (gRNA 1) and downstream (gRNA 2) gRNA target sites. Gray brackets demarcate the region to be replaced by sequences from the donor plasmid. Arrows indicate the position and orientation of PCR primers. b Partial DNA sequences of the unmodified robo3 gene and the modified robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele. Black letters indicated endogenous DNA sequence; red letters indicate exogenous sequence. Both DNA strands are illustrated. The gRNA protospacer and PAM sequences are indicated for both gRNAs. The first five base pairs of robo3 exon 2 are unaltered in the robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele, and the robo3 coding sequence beginning with codon H21 is replaced by the HA-tagged TcRobo2/3 cDNA. The endogenous robo3 transcription start site, ATG start codon, and signal peptide are retained in exon 1. The PAM sequences and portions of both protospacers are deleted in the modified allele, ensuring that the robo3 TcRobo2/3 donor plasmid and modified robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele are not targeted by Cas9. UTR untranslated regions, 5′H 5′ homology region, 3′H 3′ homology region, HA hemagglutinin epitope tag, gRNA guide RNA, HDR homology-directed repair, PAM protospacer adjacent motif

The robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele reproduces the Robo3 expression pattern

To characterize the robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele, I first compared its expression to that of the endogenous Robo3 protein in various wild-type and modified genetic strains (Fig. 3). In wild-type Drosophila embryos, Robo3 expression first becomes detectable on axons in the CNS around stage 14, when pioneering longitudinal axons begin to separate into distinguishable medial and intermediate axon pathways [6, 7, 17, 18]. By stage 16, the mature Robo3 expression pattern has been established: Robo3 protein is expressed on longitudinal axons in the intermediate and lateral regions of the neuropile and is excluded from axons within the medial region closest to the midline (Fig. 3a). In other words, axons expressing Robo3 choose to form or join longitudinal pathways within the lateral two-thirds of the axon scaffold. This is in contrast to Robo1, which is expressed on axons across the entire width of the scaffold (and has no role in lateral positioning), and Robo2, which is restricted to axons within only the most lateral region of the neuropile and promotes longitudinal pathway formation in that region [6, 7].

TcRobo2/3 expression reproduces Robo3’s expression pattern in the robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele. a–d Stage 16 Drosophila embryos stained with anti-HRP (magenta; labels all axons) and anti-Robo3 (green) antibodies. Lower images show anti-Robo3 channel alone from the same embryos. In wild-type embryos, endogenous Robo3 protein is detectable on longitudinal axons within the outer two-thirds of the neuropile (a, arrowhead). Robo3 protein is undetectable in embryos homozygous for the loss of function robo3 1 allele (b, arrowhead with asterisk) [7, 8]. There are no large-scale defects detectable with anti-HRP in the axon scaffold of robo3 1 mutants. In embryos in which the robo3 gene has been replaced with an HA-tagged robo3 cDNA, Robo3 protein expressed from the modified locus reproduces its normal expression pattern (c, arrowhead) [8]. In our CRISPR-modified embryos in which robo3 has been replaced by TcRobo2/3, Robo3 protein is undetectable, consistent with the removal of robo3 coding sequences (d, arrowhead with asterisk). e, f Stage 16 embryos stained with anti-HRP (magenta) and anti-HA (green) antibodies. Lower images show anti-HA channel alone from the same embryos. Anti-HA staining in robo3 robo3 embryos detects the Robo3 protein expressed from the modified locus and reproduces the staining pattern seen with anti-Robo3 (e, arrowhead). In robo3 TcRobo2/3 embryos, the HA-tagged TcRobo2/3 protein reproduces Robo3’s expression pattern and is detectable on longitudinal axons within the lateral two-thirds of the neuropile (f, arrowhead). Schematics of the two modified robo3 alleles are shown at lower left. The robo3 robo3 allele was generated by Spitzweck et al. [8]

In embryos homozygous for the strongly hypomorphic/null robo3 1 allele, Robo3 protein is undetectable in the CNS. Although there are longitudinal axon defects caused by the loss of robo3 (see below), there are no detectable large-scale defects in the axon scaffold in robo3 1 mutants, as assayed by an antibody against horseradish peroxidase (anti-HRP), which labels all of the axons in the CNS (Fig. 3b) [7]. Spitzweck et al. [8] previously reported a modification of the robo3 gene in which the majority of the robo3 coding exons and intervening introns were replaced by an HA-tagged robo3 cDNA (robo3 robo3). In robo3 robo3 homozygous embryos, the Robo3 protein expressed from the modified locus precisely reproduces Robo3’s normal expression pattern (Fig. 3c), and the same pattern can be seen when staining against the N-terminal HA epitope tag present in the modified allele (Fig. 3e) [8].

In the robo3 TcRobo2/3 allele, the anti-Robo3 antibody fails to detect any protein in the embryonic CNS, consistent with the replacement of the robo3 coding region with that of TcRobo2/3 (Fig. 3d). Anti-HA staining reveals that expression of the TcRobo2/3 protein in homozygous robo3 TcRobo2/3 embryos is indistinguishable from that of Robo3 in wild-type or robo3 robo3 embryos (Fig. 3f). In robo3 TcRobo2/3 embryos, TcRobo2/3 protein is localized to axons within the intermediate and lateral regions of the neuropile and is excluded from both commissural (midline crossing) axon segments and longitudinal axons in the medial neuropile. No appreciable levels of TcRobo2/3 appear to accumulate within the cell bodies of normally robo3-expressing neurons, or on the cell body plasma membrane, consistent with proper subcellular localization of the Tribolium Robo2/3 protein in this heterologous context. These observations indicate that the TcRobo2/3 protein is properly translated and trafficked within Drosophila neurons, and suggest that axons that would normally select intermediate or lateral pathways under conditions of wild-type Robo3 expression make equivalent pathway choices when TcRobo2/3 is expressed in its place.

TcRobo2/3 can promote intermediate axon pathway formation in the absence of robo3

To more closely examine the formation of longitudinal axon pathways in robo3 TcRobo2/3 embryos, I used an antibody against the cell adhesion molecule Fasciclin II (FasII) to label a subset of longitudinal axon pathways in these embryos (Fig. 4) [19]. In the ventral nerve cord of wild-type Drosophila and Tribolium embryos, at least eight distinct FasII-positive longitudinal axon pathways form at stereotypical dorsal–ventral and medial–lateral positions within the neuropile of each abdominal hemisegment [1, 11]. In Drosophila, robo3 is required for formation of FasII-positive axon pathways in the intermediate region of the neuropile, while robo2 is required for formation of lateral pathways [6, 7]. In Tribolium, TcRobo2/3 is required for proper positioning of both intermediate and lateral pathways and thus appears to combine the activities that in Drosophila are divided between robo2 and robo3 [11]. We previously hypothesized that this represents subfunctionalization between robo2 and robo3 in dipterans, and predicted that TcRobo2/3 might therefore retain the ability to rescue both robo2’s and robo3’s lateral positioning roles in Drosophila [10, 11].

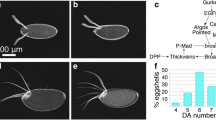

Tribolium Robo2/3 can substitute for Drosophila Robo3 to promote axon pathway formation in Drosophila embryos. a–d Stage 16 Drosophila embryos stained with anti-HRP (magenta) and anti-FasII (green) antibodies. Lower images show anti-FasII channel alone from the same embryos. In wild-type embryos, FasII-positive axons form three distinct longitudinal pathways on either side of the midline, one each in the medial, intermediate, and lateral zones of the neuropile. The intermediate FasII pathway is distinct from the medial and lateral pathways in every hemisegment in wild-type embryos (a, arrow). In robo3 1 embryos, FasII-positive axons that normally form the intermediate pathway are displaced medially, and the intermediate pathway fails to form (b, arrow with asterisk). Intermediate pathways form correctly in embryos in which the robo3 gene is replaced with a robo3 cDNA (c, arrow). When robo3 is replaced with a TcRobo2/3 cDNA, intermediate pathways form correctly in over 88% of hemisegments (d, arrow), indicating that TcRobo2/3 can substitute for robo3 to promote axon pathway formation in the intermediate region of the neuropile. Bar graph shows quantification of intermediate FasII pathway defects in the genotypes shown in a–d. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. Number of embryos scored for each genotype is indicated in parentheses. e–h Embryos carrying the sema2b-TauMyc transgene and stained with anti-HRP (blue), anti-FasII (red), and anti-Myc (green) antibodies. The sema2b-TauMyc transgene labels the cell bodies and axons of 2–3 neurons per hemisegment in abdominal segments A4–A8. These axons normally project across the midline and then extend anteriorly in the intermediate region of the neuropile (e, arrowhead). In robo3 1 embryos, these axons are displaced medially (f, arrowhead with asterisk), but their normal intermediate position is restored in both robo3 robo3 (g, arrowhead) and robo3 TcRobo2/3 embryos (h, arrowhead)

To determine whether TcRobo2/3 can act equivalently to Robo3 to promote axon pathway formation in intermediate regions of the Drosophila embryonic CNS, I used anti-FasII to examine the development of intermediate FasII-positive axon pathways in the various genetic backgrounds described above (Fig. 4). In robo3 1 mutant embryos, FasII-positive intermediate axon pathways fail to form in their proper position, instead shifting closer to the midline and merging with pathways in the medial zone (Fig. 4b) [6, 7]. This defect appears in 100% of hemisegments in robo3 1 mutants and is fully rescued when the robo3 locus is replaced with an HA-tagged wild-type robo3 cDNA (Fig. 4c) [8]. I found that proper formation of intermediate axon pathways is also restored in over 88% of hemisegments when robo3 is replaced by TcRobo2/3 (Fig. 4d), indicating that TcRobo2/3 can substitute for Drosophila robo3 to promote axon pathway formation in the fly embryonic CNS.

While FasII-positive longitudinal axon pathways are the most commonly used marker for robo3-dependent medial–lateral positioning in the Drosophila CNS, other axons rely on robo3 for their proper positioning within the intermediate neuropile, including chordotonal sensory axons and FasII-negative longitudinal axons [6, 7, 20]. To ask whether TcRobo2/3’s ability to substitute for robo3 also applies to other neuronal subsets in the Drosophila embryonic CNS, I examined a subset of neurons labeled by the sema2b-TauMyc marker, which relies on a cloned promoter fragment from the semaphorin gene sema2b to express the microtubule-binding TauMyc fusion protein in a subset of sema2b-expressing longitudinal axons [7]. These sema2b-positive axons do not express FasII, and they cross the midline to form a contralateral longitudinal pathway in the intermediate neuropile at an earlier timepoint than the FasII-positive axons examined above [5] (Fig. 4e). Consistent with previous reports, I found that the sema2b axons are shifted to a medial position in robo3 1 mutants, but select their normal intermediate position in robo3 robo3 embryos [7, 8] (Fig. 4f, g). In robo3 TcRobo2/3 embryos, the sema2b axons also select their normal intermediate position, indicating that TcRobo2/3 can substitute for robo3 to direct these axons to the intermediate region of the neuropile. Together, these results demonstrate that Tribolium Robo2/3 can act equivalently to Drosophila robo3 to specify an intermediate lateral position in at least two distinct sets of interneurons in the fly embryonic CNS.

Discussion

In this paper, I have used a CRISPR/Cas9-based gene replacement approach to directly examine the evolutionary conservation of axon guidance activities within the Robo family of axon guidance receptors. I have replaced the Drosophila melanogaster robo3 gene with its ortholog from the flour beetle Tribolium castaneum, TcRobo2/3. I compared the expression of TcRobo2/3 protein in this modified background with the normal expression of Robo3 in wild-type embryos and examined Robo3-dependent guidance of two distinct subsets of longitudinal axons in the ventral nerve cord of wild-type, robo3 mutant, and robo3 TcRobo2/3 gene replacement embryos. My results suggest that the mechanism(s) by which robo3 and TcRobo2/3 regulate axon guidance outcomes in the Drosophila and Tribolium embryonic CNS, respectively, are evolutionarily conserved. In addition, the gene replacement approach described here should be broadly applicable to evo-devo studies of other genes in Drosophila and other insects.

Evolutionary conservation of Robo3-dependent axon guidance mechanisms

Three lines of evidence suggest that TcRobo2/3 can act equivalently to Robo3 to guide Drosophila axons: (1) The subset of longitudinal axons that normally express Robo3 are still localized to the lateral two-thirds of the neuropile when they express TcRobo2/3 instead of Robo3; (2) FasII-positive axon pathways in the intermediate neuropile form in their proper location when robo3 is replaced by TcRobo2/3; and (3) sema2b-positive longitudinal axons also select their correct intermediate position when robo3 is replaced by TcRobo2/3. These observations, together with a previous report that RNAi-mediated knockdown of TcRobo2/3 disrupts intermediate pathway formation in the Tribolium embryonic CNS [11], suggest that the mechanism by which Drosophila Robo3 promotes longitudinal pathway formation is evolutionarily conserved in Tribolium, where it is performed by TcRobo2/3. CRISPR approaches have recently been used successfully in Tribolium [21], so it should be possible to perform the complementary experiments by replacing TcRobo2/3 with Drosophila robo3. In this case, robo3 should be able to replace the function of TcRobo2/3 to promote intermediate pathway formation, but the lateral pathways (which presumably depend on a robo2-like activity of TcRobo2/3) may not form properly.

The observation that TcRobo2/3 can fully substitute for Robo3 to regulate intermediate pathway formation in the Drosophila embryonic CNS suggests that any sequences that are necessary for this role in Robo3 are conserved in TcRobo2/3. Notably, the highest degree of sequence conservation between these two proteins occurs within the extracellular Ig1 and Ig3 domains (Fig. 1; 77 and 66% identity, respectively); these two domains have also been implicated in Drosophila Robo2 in its role in promoting lateral axon pathway formation [9]. While it is not yet known whether Robo2 and Robo3 regulate longitudinal pathway formation via the same mechanism, there are clearly sequences within Robo2 that are not conserved in Robo3 that are essential for guidance of lateral axons [8]. By comparing the conservation and divergence of sequences within Drosophila Robo2, Drosophila Robo3, and Tribolium Robo2/3, it may be possible to identify individual amino acids or short sequence motifs that distinguish between the functions of these proteins.

Both cytoplasmic CC sequences (CC0 and CC1) are conserved in Robo3 and Robo2/3, but there is little conservation in the cytodomain outside of these motifs (Fig. 1). Notably, both CC0 and CC1 are also present in Drosophila Robo1 and Robo2, which can both substitute for Robo3 to promote intermediate pathway formation [8]. Thus, if Robo3 acts as a canonical Slit receptor to regulate longitudinal axon guidance, it is likely that this role is dependent on its CC0 and/or CC1 motifs.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene replacement for studies in evolutionary developmental biology

The gene replacement approach described here has several advantages for both structure–function studies and evo-devo functional comparisons of orthologs from different species. First, replacing multiple coding exons in the endogenous gene with a single cDNA sequence allows for epitope tagging of the modified locus in addition to replacing the entire coding region with a foreign sequence or a modified cDNA carrying engineered deletions, additions, or sequence swaps. For multi-exon genes, this eliminates the need to replace multiple exons individually. Second, the endogenous promoter and translational start site remain unmodified, minimizing effects on gene expression. Third, using two gRNA targets that flank the majority of the gene should allow recovery of a null deletion allele via non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) in addition to the HDR-mediated gene replacement allele. This would be of particular benefit for genes for which a null allele is not currently available. Finally, this approach allows the same gRNA plasmid and donor backbone to be used for multiple gene replacement experiments, minimizing troubleshooting and optimization for each subsequent experiment. We have used the same donor construct backbone to replace robo3 with modified versions of itself and other Drosophila robo genes, and have also recovered a precise deletion of all sequences between the robo3 gRNA targets (A. Carranza and T.A.E., unpublished). A similar approach should be applicable to other genes assuming that, like all three Drosophila robo genes, the introns that would be removed by the cDNA replacement are dispensable for proper expression of the gene to be modified.

Conclusions

Here I have described a strategy for CRISPR/Cas9-based trans-species gene replacement in Drosophila and used this strategy to demonstrate the evolutionary conservation of axon guidance mechanism(s) between the Drosophila robo3 and Tribolium robo2/3 genes. When expressed from the robo3 locus, TcRobo2/3 protein is properly translated and localized to neuronal axons in the Drosophila embryonic CNS and can guide developing axons to pathways in the intermediate region of the neuropile in an equivalent manner to Drosophila Robo3. The approach described here should be generally applicable to other genes and developmental contexts and will be useful to interrogate the evolutionary conservation or divergence of additional axon guidance mechanisms in insects.

Abbreviations

- CNS:

-

central nervous system

- Robo:

-

Roundabout

- Sema:

-

semaphorin

- FasII:

-

Fasciclin II

- CRISPR:

-

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- HDR:

-

homology-directed repair

- gRNA:

-

guide RNA

- PAM:

-

protospacer adjacent motif

- Ig:

-

immunoglobulin-like domain

- Fn:

-

fibronectin type III repeat

- Tm:

-

transmembrane helix

- CC:

-

conserved cytoplasmic motif

- UTR:

-

untranslated region

- 5′H:

-

5′ homology region

- 3′H:

-

3′ homology region

- HA:

-

hemagglutinin epitope tag

- HRP:

-

horseradish peroxidase

- BDSC:

-

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center

References

Landgraf M, Sánchez-Soriano N, Technau GM, Urban J, Prokop A. Charting the Drosophila neuropile: a strategy for the standardised characterisation of genetically amenable neurites. Dev Biol. 2003;260:207–25.

Rickert C, Kunz T, Harris K-L, Whitington PM, Technau GM. Morphological characterization of the entire interneuron population reveals principles of neuromere organization in the ventral nerve cord of Drosophila. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15870–83.

Mauss A, Tripodi M, Evers JF, Landgraf M. Midline signalling systems direct the formation of a neural map by dendritic targeting in the Drosophila motor system. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000200.

Zlatic M, Li F, Strigini M, Grueber W, Bate M. Positional cues in the Drosophila nerve cord: semaphorins pattern the dorso-ventral axis. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000135.

Wu Z, Sweeney LB, Ayoob JC, Chak K, Andreone BJ, Ohyama T, et al. A combinatorial semaphorin code instructs the initial steps of sensory circuit assembly in the Drosophila CNS. Neuron. 2011;70:281–98.

Simpson JH, Bland KS, Fetter RD, Goodman CS. Short-range and long-range guidance by Slit and its Robo receptors: a combinatorial code of Robo receptors controls lateral position. Cell. 2000;103:1019–32.

Rajagopalan S, Vivancos V, Nicolas E, Dickson BJ. Selecting a longitudinal pathway: Robo receptors specify the lateral position of axons in the Drosophila CNS. Cell. 2000;103:1033–45.

Spitzweck B, Brankatschk M, Dickson BJ. Distinct protein domains and expression patterns confer divergent axon guidance functions for Drosophila Robo receptors. Cell. 2010;140:409–20.

Evans TA, Bashaw GJ. Functional diversity of Robo receptor immunoglobulin domains promotes distinct axon guidance decisions. Curr Biol. 2010;20:567–72.

Evans TA. Embryonic axon guidance: insights from Drosophila and other insects. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2016;18:11–6.

Evans TA, Bashaw GJ. Slit/Robo-mediated axon guidance in Tribolium and Drosophila: divergent genetic programs build insect nervous systems. Dev Biol. 2012;363:266–78.

Li X-T, Yu Q, Zhou Q-S, Zhao X, Liu Z-Y, Cui W-Z, et al. BmRobo2/3 is required for axon guidance in the silkworm Bombyx mori. Gene. 2016;577(2):174–9.

Dickson BJ, Gilestro GF. Regulation of commissural axon pathfinding by slit and its Robo receptors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:651–75.

Port F, Chen H-M, Lee T, Bullock SL. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:E2967–76.

Patel NH. Imaging neuronal subsets and other cell types in whole-mount Drosophila embryos and larvae using antibody probes. Methods in cell biology. Elsevier. 1994;44:445–87.

Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–82.

Simpson JH, Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Short-range and long-range guidance by slit and its Robo receptors. Robo and Robo2 play distinct roles in midline guidance. Neuron. 2000;28:753–66.

Rajagopalan S, Nicolas E, Vivancos V, Berger J, Dickson BJ. Crossing the midline: roles and regulation of Robo receptors. Neuron. 2000;28:767–77.

Grenningloh G, Rehm EJ, Goodman CS. Genetic analysis of growth cone guidance in Drosophila: fasciclin II functions as a neuronal recognition molecule. Cell. 1991;67:45–57.

Zlatic M, Landgraf M, Bate M. Genetic specification of axonal arbors: atonal regulates robo3 to position terminal branches in the Drosophila nervous system. Neuron. 2003;37:41–51.

Gilles AF, Schinko JB, Averof M. Efficient CRISPR-mediated gene targeting and transgene replacement in the beetle Tribolium castaneum. Development. 2015;142:2832–9.

Acknowledgements

I thank Abigail Carranza, who constructed the initial robo3 CRISPR donor backbone. Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) were used in this study. Monoclonal antibodies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, created by the NICHD of the NIH, and maintained at the University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City, IA 52242.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated during this study are included in this published article. Drosophila strains and recombinant DNA plasmids are available upon request.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R15 NS098406 (T.A.E.) and by funds from the University of Arkansas. The funders had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Evans, T.A. CRISPR-based gene replacement reveals evolutionarily conserved axon guidance functions of Drosophila Robo3 and Tribolium Robo2/3. EvoDevo 8, 10 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-017-0073-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13227-017-0073-y