Abstract

Background

Highly Active Antiretroviral therapy (HAART) reverses the effect of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) by durably suppressing viral replication. This allows CD4 gain to levels that are adequate enough to restore the body’s capability to fight against opportunistic infections (OIs). Patients with poor immune recovery have been shown to have higher risk of developing both AIDS and non AIDS related clinical events. This study aimed at assessing the proportions and risk factors of poor immune recovery in adult HIV-infected patients on 48 months of HAART attending care and treatment center (CTC) in northwestern Tanzania.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of adult HIV patients’ data attending CTC at Sekou Toure hospital and who initiated HAART between February 2004 and January 2008 was done. Poor immune recovery was defined as a CD4 count less than 350 cells/µl on follow up as used in other studies.

Results

A total of 734 patients were included in the study. In this study 50.25% of patients attending CTC at Sekou Toure hospital were found to have poor immune recovery. The risk of developing inadequate immune recovery was independently associated with male gender, age older than 50 years, low baseline CD4 counts, and advanced World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage.

Conclusions

Poor immune recovery is prevalent among adult HIV patients attending CTC at Sekou Toure hospital in Northwestern part of Tanzania and opportunistic infections are common in this sub group of patients. Clinicians in resource limited countries need to identify these patients timely and plan them for targeted viral assessment and close clinical follow up to improve their long term clinical outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HIV is known to infect CD4 positive cells and its replication in these immune cells causes progressive lysis and reduction of the number and quality of functional immune cells [1,2,3]. With time the body fails to contain the viral replication and immune deficiency sets in, being marked by low CD4 counts with increased morbidity and mortality from opportunistic infections [4]. The use of potent HAART is intended to induce sustained suppression of HIV viral replication allowing CD4 regain and restore the body’s ability to fight against opportunistic infections [5,6,7,8,9]. Since the arrival of HAART it has been shown that there is a significant reduction of both AIDS and non AIDS related morbidity and mortality in People Living With HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) [5, 10,11,12,13,14], especially in those who achieve an adequate immune recovery. In most patients adequate CD4 regain is characterized by an increase of about 50-150 cells/µl in the first year followed by 50–100 cells/µl in subsequent years [15]; reaching an immunological threshold of CD4 >350–500 cells/µl in 4–7 years of effective HAART [8, 16, 17]. This immunological threshold is clinically important in view of the fact that patients who regain their CD4 to this immunological point have a better clinical outcome with non AIDS events almost comparable to normal populations [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Otherwise patients whose rate of CD4 regain is less than 50 cells/µl a year may possibly take a much longer time [24,25,26,27], before reaching this immunological threshold and this subgroup of patients has been shown to be at higher risk of both AIDS and non AIDS related morbidities and mortalities [28,29,30,31]. Poor immune recovery represents a very frequent problem in clinical practice worldwide with a prevalence which can be in excess of 50%. In view of this information WHO recommends early identification of patients who fail on HAART by using clinical-immune monitoring as a surrogate marker of treatment response and plan them for targeted virological confirmation. Even though poor immune response is so prevalent, there is no prior documentation of the magnitude of this problem in Tanzania. Our study aimed at determining the proportion and risk factors of poor immune recovery in adult HIV patients on standard HAART for 48 months in Northwestern Tanzania. This will assist clinicians in Tanzania and other resource limited settings to be able to identify potential patients who may possibly benefit from targeted viral load testing and close clinical follow up.

Methods

This was a retrospective study involving all adult HIV positive patients (age ≥18 years) who started on antiretroviral therapy at Sekouture hospital care and treatment center. Children and adult patients who were yet to be on ART were excluded. Sekouture is a regional referral hospital located in Mwanza, in north western part of Tanzania. A retrospective analysis of 4 years data of HIV patients initiated on HAART between 20th February 2004 and 20th January 2008 was done. In this study HAART was referred to as a combination of 2 Nucleoside reverse transcriptase and one non nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor or a protease inhibitor with or without a pharmacological booster.

The variables collected included age, sex, marital status, occupation, baseline CD4 count, occurrence of opportunistic infections within 4 years of follow up at CTC, body weight and CD4 count at 48 months of follow up. Data were managed using Epi Data 3.1 (CDC Atlanta, US) and analysis was done using STATA version 12 (College Station, Texas, US). The baseline CD4 counts were categorized into two using cut off point CD4 of 200 cells/µl and patients with CD4 counts of less than 200 cells/µl at base line were referred as presenting with severe immune suppression. The immune response at 48 months of follow up was also divided into two groups with cut off point CD4 of 350 cells/µl as used in other studies [32]. Immune reconstitution was defined as CD4 count ≥350 cells/µl; at 48 months of follow up and those patients who had CD4 counts <350 cells/µl at 48 months were defined as having poor immune recovery. The categorical variables were summarized as proportions and their significance of difference in distribution within the categories of immune response was assessed using Pearson’s Chi square test or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate. Parametric continuous data were summarized as mean with standard deviation and the significance of difference in means within the two groups was assessed using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Non-parametric continuous data were summarized as median with interquartile range and the difference in medians within the categories of immune response was compared using Kruskal–Wallis equality-of-populations rank test. The odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of risk factors associated with poor immune recovery were calculated using univariate logistic regression model followed by multivariate logistic regression model. All risk factors associated with poor immune recovery in the univariate analysis with p values less than 0.05 were considered for inclusion in the multivariate model. A stepwise approach was used to derive a Parsimonious model, and all associated factors in the final model were considered significant if the p value was less than 0.05.

Study results

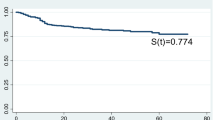

In total 734 patients were included in this study; in which most patients were females (66.76%), with a median age of 39.03(21–60) years. Most of patients (52%) were married, unemployed (89%) and in WHO clinical stage 3 and 4 (57.49%). Of these patients 722 (98.4%) had recorded baseline CD4, where more than 75 percent; 545 (75.48%) had baseline CD4 counts of less than 200 cells/µl, while 670 (92.27%) had baseline CD4 counts <350 cells/µl as summarized in Table 1. And at 48 moths of follow up, 593(80.8%) of 734 patients had recorded CD4 counts; of these 289 (50.25%) had CD4 count <350 cells/µl. Patients with poor immune recovery were more likely to be male in gender (OR = 1.52, p = 0.039) and older than 50 years (OR = 4.17, p < 0.001), with baseline CD4 count of less than 200 cells/µl (OR = 4.32, p < 0.001), in WHO clinical stage 3 and 4 (OR = 1.47, p = 0.043). Patients with poor immunological recovery also had higher occurrence of an opportunistic infection (OR = 4.32, p < 0.001). The difference in distribution of other factors was not significant including the type of opportunistic infections as summarized in Table 2.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the proportion and risk factors of poor immunological response to HAART in adult HIV patients attending CTC in northwestern Tanzania for 48 months. Of the 593 patients who had records of their CD4, 289 (50.25%) did not reach an immunological threshold of ≥350 cells/µl at 4 years of HAART. This prevalence seems slightly higher than those reported from developed countries. In one study in Australia Kaufmann et al. indicated that about 14% of the virologically suppressed patients didn’t reach an immunological cut off point of 350 cells/µl at four years of HAART [8]. Another study in United States of America (USA) defining inadequate immune recovery as a CD4 gain of less than 150 cells/µl a year reported a prevalence of 36% in patients who were virologically suppressed [33]. While a study in San Francisco with CD4 count cut off of 350 cells/µl; 41% did not reach this immunological threshold [16]. Of note from these studies as might be true with most of other studies from developed countries these rates represent poor immune recovery in patients who were virologically suppressed. Our study represents one of the studies from resource limited settings where virological monitoring of treatment response is not obtainable and feasible for routine practice. In these settings patients with inadequate immune recovery is a heterogeneous group which takes in both concordant and discordant non responders making the prevalence higher than what is reported from studies that exclude concordant non responders [34]. In Uganda; Nanzigu et al. reported a slightly higher rate of poor immune recovery (62.9%) at 5 years with cut off point of 418 cells/µl [35]. However; even with these differences, the clinical relevance drawn from these studies remains similar. Previous studies have indicated that patients with poor immune response to HAART have increased risk of AIDS progression with higher rates of both AIDS and non AIDS related clinical events [12, 29, 36], even with complete virological suppression. Similarly in our study we observed that patients with poor immune recovery had higher rates of OI as compared to those who reached the immunological threshold of >350 cells/µl (71.14% vs. 40%, p < 0.001). In our study we found that male gender was strongly associated with poor immune recovery where male patients were 1.52 times more likely to have poor immune recovery than females. Several other studies have indicated that female patients have a better and faster immune recovery than men [16, 26, 35, 37]. This may possibly be explained by the hormonal regulatory effect on CD4 numbers. In this regard females have been shown to have comparatively higher CD4 level than men which is estrogen regulated [38], and with use of suppressive HAART this normal homeostatic regulation of CD4 cell number may therefore lead into higher CD4 gain in females than men [37]. The other risk factor was being older than 50 years (OR = 4.17, p < 0.001). This is in agreement with other studies [35, 36, 39]. Older patients probably have reduced thymus functions and other degenerative processes as suggested in most studies [8, 36, 40,41,42]. Clinically this suggests that there should perhaps be screening programs in ages close to 50 for early diagnosis and timely initiation of HAART. A baseline CD4 count <200 cells/µl was another risk factor which was independently associated with inadequate immune recovery, (OR = 4.32, p = 0.001). Low CD4 counts represent a severe immune destruction and patients who start ART at lower baseline CD4 bellow 200 cells/µl have been demonstrated to have a poor immune recovery [24, 36, 43]. Hunt et al. demonstrated that only about 21–49% of patients who start ART at CD4 counts of <200 cells/µl achieved CD4 counts of 350–500 cells/µl at 4 years while more than 93% of those who initiated HAART at CD4 levels >200 to 350 cells/µl attained CD4 levels >350 to 500 cells/µl at four years [16]. This emphasizes further on the value of starting HAART at cut off point of CD4 ≥350 cells/µl [13, 44]. It was also observed that patients in WHO stage 3 and 4 were 1.47 times more likely to have inadequate immune recovery on receipt of HAART as compared to those in WHO stage 1 and 2 (OR = 1.47, p = 0.043). Kaufmann et al. had similar observation that patients in advanced HIV stage had poor immune recovery as compared to those in early stage of the disease [8]. These findings suggest that patients who present late in advanced HIV/AIDS and severe immune suppression need a much closer clinical follow up to improve their outcome.

This study had a number of limitations. It was a single site clinic based study and therefore findings may not be generalizable to the general population. Being a retrospective study, the data was obtained from patients’ files; these are most of times incomplete; some of the important variables were missing including information on compliance to medications and missing CD4 counts at 48 months. In this study about 141(19.21%) patients had missing CD4 records at 48 month, on a sub analysis (not shown) most of them 98(70.5%) had baseline CD4 <200 cells/µl indicating that they were more likely to have poor immune response at 48 months of follow up and this could have made the burden of poor immune recovery probably more worse. However even with these limitations our study has a number of strengths inclusive of being a relatively large sample size study that describes immune recovery in patients initiated on HAART at low baseline CD4 counts.

Conclusions

Poor immune recovery is common in Northwestern Tanzania. This is strongly associated with male gender, older age than 50 years, low baseline CD4 count, advanced clinical stage and occurrence of opportunistic conditions. Clinicians from resource limited settings should identify potential patients and plan them for a much closer clinical follow up and targeted plasma viral load since this subgroup of patients have poor clinical outcomes.

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- BMC:

-

Bugando medical center

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CD4:

-

cluster of differentiation 4

- CDC:

-

Center for Disease Control

- CTC:

-

care and treatment Center

- CUHAS:

-

Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences

- HAART:

-

highly active antiretroviral therapy

- IQR:

-

inter quartile range

- OIs:

-

opportunistic infections

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PLWHA:

-

people living with HIV/AIDS

- US:

-

United States

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Martin N, Sattentau Q. Cell-to-cell HIV-1 spread and its implications for immune evasion. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(2):143–9.

Alexaki A, Liu Y, Wigdahl B. Cellular reservoirs of HIV-1 and their role in viral persistence. Curr HIV Res. 2008;6(5):388–400.

Ford ES, Puronen CE, Sereti I. Immunopathogenesis of asymptomatic chronic HIV Infection: the calm before the storm. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2009;4(3):206–14.

Brooks JT, et al. HIV-associated opportunistic infections–going, going, but not gone: the continued need for prevention and treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):609–11.

Palella FJ Jr, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–60.

Raboud JM, et al. Suppression of plasma viral load below 20 copies/ml is required to achieve a long-term response to therapy. AIDS. 1998;12(13):1619–24.

Lange CG, Lederman MM. Immune reconstitution with antiretroviral therapies in chronic HIV-1 infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(1):1–4.

Kaufmann GR, et al. The extent of HIV-1-related immunodeficiency and age predict the long-term CD4 T lymphocyte response to potent antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2002;16(3):359–67.

Autran B, et al. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997;277(5322):112–6.

Mocroft A, et al. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. EuroSIDA Study Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1725–30.

Vittinghoff E, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and recent declines in AIDS incidence and mortality. J Infect Dis. 1999;179(3):717–20.

Egger M, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9327):119–29.

Garcia F, et al. Long-term CD4+ T-cell response to highly active antiretroviral therapy according to baseline CD4+ T-cell count. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(2):702–13.

Mocroft A, et al. Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: an observational study. Lancet. 2003;362(9377):22–9.

Kaufmann GR, et al. CD4 T-lymphocyte recovery in individuals with advanced HIV-1 infection receiving potent antiretroviral therapy for 4 years: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(18):2187–95.

Hunt PW, et al. Continued CD4 cell count increases in HIV-infected adults experiencing 4 years of viral suppression on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2003;17(13):1907–15.

Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Washington, D.D.o.H.a.H.S., Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1 infected adults and adolescents. 2008.

Lau B, Gange SJ, Moore RD. Risk of non-AIDS-related mortality may exceed risk of AIDS-related mortality among individuals enrolling into care with CD4+ counts greater than 200 cells/mm3. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(2):179–87.

Marin B, et al. Non-AIDS-defining deaths and immunodeficiency in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2009;23(13):1743–53.

Lewden C, et al. HIV-infected adults with a CD4 cell count greater than 500 cells/mm3 on long-term combination antiretroviral therapy reach same mortality rates as the general population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(1):72–7.

Obel N, et al. Impact of non-HIV and HIV risk factors on survival in HIV-infected patients on HAART: a population-based nationwide cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e22698.

Rodger AJ, et al. Mortality in well controlled HIV in the continuous antiretroviral therapy arms of the SMART and ESPRIT trials compared with the general population. AIDS. 2013;27(6):973–9.

Lewden C, et al. All-cause mortality in treated HIV-infected adults with CD4>/=500/mm3 compared with the general population: evidence from a large European observational cohort collaboration. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):433–45.

Le Moing V, et al. Long-term evolution of CD4 count in patients with a plasma HIV RNA persistently < 500 copies/mL during treatment with antiretroviral drugs. HIV Med. 2007;8(3):156–63.

Luz PM, et al. Long-term CD4+ cell count in response to combination antiretroviral therapy. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e93039.

Kelley CF, et al. Incomplete peripheral CD4+ cell count restoration in HIV-infected patients receiving long-term antiretroviral treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(6):787–94.

Rajasuriar R, et al. Clinical predictors of immune reconstitution following combination antiretroviral therapy in patients from the Australian HIV Observational Database. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(6):e20713.

Baker JV, et al. CD4+ count and risk of non-AIDS diseases following initial treatment for HIV infection. AIDS. 2008;22(7):841–8.

Baker JV, et al. Poor initial CD4+ recovery with antiretroviral therapy prolongs immune depletion and increases risk for AIDS and non-AIDS diseases. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;48(5):541–6.

Lichtenstein KA, et al. Low CD4+ T cell count is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease events in the HIV outpatient study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(4):435–47.

Mzileni MO, Longo-Mbenza B, Chephe TJ. Mortality and causes of death in HIV-positive patients receiving antiretroviral therapy at Tshepang Clinic in Doctor George Mukhari Hospital. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2008;118(10):548–54.

Cuzin L, et al. Immunologic and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection aged > 50 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(5):654–7.

Onen NF, et al. Sub-optimal CD4 recovery on long-term suppressive highly active antiretroviral therapy is associated with favourable outcome. HIV Med. 2009;10(7):439–46.

Misgena DK. The pattern of immunologic and virologic responses to Highly Active Antiretroviral Treatment (HAART): does success bring further challenges? Ethiop J Health Dev. 2011;25(1):61–70.

Nanzigu S, et al. Poor immunological recovery among severely immunosuppressed antiretroviral therapy-naive Ugandans. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2013;5:309–19.

Kaufmann GR, et al. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to < 500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(3):361–72.

Gandhi RT, et al. Effect of baseline- and treatment-related factors on immunologic recovery after initiation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-positive subjects: results from ACTG 384. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(4):426–34.

Maini MK, et al. Reference ranges and sources of variability of CD4 counts in HIV-seronegative women and men. Genitourin Med. 1996;72(1):27–31.

Viard JP, et al. Influence of age on CD4 cell recovery in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy: evidence from the EuroSIDA study. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(8):1290–4.

Khoury G, et al. The role of naive T-cells in HIV-1 pathogenesis: an emerging key player. Clin Immunol. 2011;141(3):253–67.

Gaardbo JC, et al. Incomplete immune recovery in HIV infection: mechanisms, relevance for clinical care, and possible solutions. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:670957.

Althoff KN, et al. Virologic and immunologic response to HAART, by age and regimen class. AIDS. 2010;24(16):2469–79.

Moore RD, Keruly JC. CD4 + cell count 6 years after commencement of highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with sustained virologic suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(3):441–6.

Yeni PG, et al. Treatment for adult HIV infection: 2004 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2004;292(2):251–65.

Authors’ contributions

DWG, SBK and BCM, conceived, designed and acquired the data. DWG and BCM analyzed the data. SBK and BCM interpreted the data. DWG drafted the manuscript. BCM, EK, EZR and SBK critically revised the manuscript for key intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance provided by members of staff at HIV Care and Treatment Clinic, Sekou Toure Regional/Referral Hospital.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The permission to conduct this study and publish the findings was granted by The Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences and Bugando Medical Centre (CUHAS/BMC) joint ethics review board. The consent to participate wasn’t applicable in this study. Patients’ records were reviewed by researchers, patients’ identifiers were not collected, and confidentiality was not violated.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gunda, D.W., Kilonzo, S.B., Kamugisha, E. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of poor immune recovery among adult HIV patients attending care and treatment centre in northwestern Tanzania following the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a retrospective study. BMC Res Notes 10, 197 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2521-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2521-0