Abstract

Background

Few studies have measured device-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour following a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), with no studies comparing these behaviours between countries using the same methods. The aim of the study was to compare device-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour, using a harmonised approach, following a PCI on-entry into centre-based cardiac rehabilitation in two countries.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at two outpatient cardiac rehabilitation centres in Australia and Sweden. Participants were adults following a PCI and commencing cardiac rehabilitation (Australia n = 50, Sweden n = 133). Prior to discharge from hospital, Australian participants received brief physical activity advice (< 5 mins), while Swedish participants received physical activity counselling for 30 min. A triaxial accelerometer (Actigraph GT3X/ActiSleep) was used to objectively assess physical activity (light (LPA), moderate-to-vigorous (MVPA)) and sedentary behaviour. Outcomes included daily minutes of physical activity and sedentary behaviour, and the proportion and distribution of time spent in each behaviour.

Results

There was no difference in age, gender or relationship status between countries. Swedish (S) participants commenced cardiac rehabilitation later than Australian (A) participants (days post-PCI A 16 vs S 22, p < 0.001). Proportionally, Swedish participants were significantly more physically active and less sedentary than Australian participants (LPA A 27% vs S 30%, p < 0.05; MVPA A 5% vs S 7%, p < 0.01; sedentary behaviour A 68% vs S 63%, p < 0.001). When adjusting for wear-time, Australian participants were doing less MVPA minutes (A 42 vs S 64, p < 0.001) and more sedentary behaviour minutes (A 573 vs S 571, p < 0.001) per day. Both Swedish and Australian participants spent a large part of the day sedentary, accumulating 9.5 h per day in sedentary behaviour.

Conclusion

Swedish PCI participants when commencing cardiac rehabilitation are more physically active than Australian participants. Potential explanatory factors are differences in post-PCI in-hospital physical activity education between countries and pre-existing physical activity levels. Despite this, sedentary behaviour is high in both countries. Internationally, interventions to address sedentary behaviour are indicated post-PCI, in both the acute setting and cardiac rehabilitation, in addition to traditional physical activity and cardiac rehabilitation recommendations.

Trial registrations

Australia: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR): ACTRN12615000995572. Registered 22 September 2015, Sweden: World Health Organization Trial Registration Data Set: NCT02895451.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the most commonly used procedure for myocardial revascularisation globally [1, 2]. Both Australian [3,4,5] and European (applied in Sweden) clinical guidelines [6] for the management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) recommend that all individuals hospitalised with ACS, including those undergoing a PCI, should receive physical activity counselling and referral to a cardiac rehabilitation program prior to discharge. Meta-analysis clearly confirm that participation in exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation is associated with positive health benefits in terms of reduced cardiac mortality, risk of hospital readmission and improved aerobic capacity for patients with an ACS [7]. Additionally, studies assessing physical activity in patients with ACS have established an inverse relationship between increased levels of physical activity and mortality [8,9,10]. Although, these studies are limited to self-reported physical activity, entailing a risk of over- or under-estimating physical activity, as well as issues of recall and response bias [11]. Accelerometry is considered a superior method of physical activity measurement, with lower levels of variability observed for validity and reliability, overcoming limitations of self-reports [12]. However in patients with ACS, few studies have measured device-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour (a risk factor for all-cause mortality in people with cardiovascular disease [13]) following a PCI [14,15,16,17]. All of these studies have used different measurement devices (Sensewear Armband, GENEActiv, ActiCal, ActiGraph) and different measures of physical activity and sedentary behaviour (minutes per day, percentage wear time, ≥ 1 day exercising) making it difficult to compare results. No studies have used the same methods to compare device-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour between countries in this population.

International comparisons provide a broader perspective of health and health care, potentially identifying best practice and factors that may influence outcomes [18]. The data (definitions, participants, time period) and methods used in these comparisons should be similar so differences, if any, can be clearly identified and appropriate conclusions can be made [18]. Australia and Sweden both have a very high Human Development Index, a composite measure of life expectancy, education and income, ranked third and seventh in the world respectively [19]. They are both members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, having similar levels of economic development [20]. Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death and disease burden in Australia [21] and in Sweden [22]. In 2000, 21,784 PCI procedures were performed in Australia, increasing to 41,200 in 2016 [2, 23]. Approximately 75% of Australians with a diagnosis of ST-elevated myocardial infarction were treated with a PCI procedure in 2012–2015 [24]. In Sweden, 10,000 PCI procedures were performed in 2000, which has doubled to over 20,000 procedures in 2018 [25]. Therefore, it appears it is appropriate to quantify and compare physical activity and sedentary behaviour in this group of patients following a PCI in these two countries.

In cardiac rehabilitation (including PCI participants), device-based physical activity levels have been reported as low (approximately 11 min moderate-intensity physical activity a day [26, 27]), and sedentary behaviour high (approximately 8–10 h a day [17, 27]). Currently, it is difficult to compare device-based physical activity in cardiac populations around the world, with a variety of different data collection and processing methods utilised. Here we describe a method to assess physical activity and sedentary behaviour in post-PCI participants’ on-entry into cardiac rehabilitation. This will allow comparison of physical activity and sedentary behaviour levels internationally post-PCI, providing an indication of differences between countries and the discussion of possible explanatory factors. Results could guide acute post-PCI management and cardiac rehabilitation guidelines internationally. The aim of the study was to compare device-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour, using the same methods, following a PCI on-entry into centre-based cardiac rehabilitation in two countries.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the commencement of phase II cardiac rehabilitation at one centre in Australia and Sweden. In Australia, the cardiac rehabilitation program involved both exercise and education sessions at every attendance. In Sweden, patients were offered exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation and education sessions separately. Most patients start the weekly education sessions 1 week from hospital discharge and before they commence the exercise sessions. The education sessions cover three different topics: 1) Heart disease and risk factors, 2) Psychological aspects related to heart disease, 3) Diet and exercise. The majority of patients do not complete the education session on diet and exercise until after they start the exercise sessions. In this study, Swedish participants were included prior to the start of the exercise sessions. As all participants were assessed on-entry into exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation, any differences in exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation guidelines between countries were not relevant as no participants had commenced the exercise sessions. The participants were a subset of participants from larger studies conducted in both countries. The Australian and Swedish study protocols have been described elsewhere, as well as results from the larger Australian cohort study [28,29,30,31].

Participants

Eligible participants were aged ≥18 years (Australia and Sweden) and < 75 years (Sweden) and had agreed to start the cardiac rehabilitation program. Consecutive participants were included if they had stable coronary heart disease and had received a PCI +/− myocardial infarction. Participants were recruited between November 2015 and August 2016 in Australia, and between January 2016 and August 2018 in Sweden. All participants provided written consent.

Post-PCI physical activity and cardiac rehabilitation advice

At the Australian hospital, all post-PCI patients are seen by cardiac rehabilitation or cardiology nurses prior to discharge and are encouraged to start regular, low-to-moderate intensity physical activity, starting slowly and progressing gradually. This advice is brief, approximately 5-min, and is supported with written material from the National Heart Foundation, initially encouraging 5 to 10 min strolls twice a day [32]. At the Swedish hospital, patient’s post-PCI meet with a physiotherapist for 20 to 30-min prior to discharge for physical activity counselling [33]. Patients post-PCI are encouraged to start regular moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) as soon as possible, and the recommended dose is consistent with the general global recommendation on physical activity for health; 30 min of at least moderate intensity aerobic activity on 5 days a week [6, 34]. In Australia and Sweden, all patients are referred and encouraged to attend an outpatient cardiac rehabilitation program, commencing soon after discharge from hospital.

Outcome measures

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour

A triaxial commercial accelerometer (ActiGraph ActiSleep or GT3XFootnote 1) was used to objectively assess physical activity and sedentary behavior in both countries. Participants were asked to wear the monitor on their right hip for 24-h per day (Australian sample) or during waking hours (Swedish sample), for 7-consecutive days. For the Australian data, to eliminate sleep time a time filter was applied from 7 am to 10.30 pm, the average time out-of- and into-bed each day based on participants’ surveys, only analyzing data between these times. Participants were instructed not to wear the accelerometer in water. The triaxial accelerometer captures movement around three axes; vertical (y-axis), horizontal (x-axis) and perpendicular (z-axis). Vector magnitude is a composite measure of all 3 axes (√x2 + y2 + z2). A review of the literature was conducted to determine the most suitable parameters for accelerometer data processing in participants with coronary heart disease [17, 27, 35,36,37].

Accelerometer sampling, epoch length and wear time

All data was sampled and downloaded as raw data (30 Hz), converted to 15-s epochs (time interval), and then counts per minute (cpm) using the Actilife1 software [17, 27]. A ‘count’ is the unit of measure for activity for ActiGraph’s activity monitors [38]. Data was screened, excluding data if: < 10 h per day wear time (non-wear defined as > 60 consecutive minutes where there is zero activity, with no allowance of epochs with counts above zero) and less than 4 days of valid data [17, 27, 35]. If there was more than 7 days of valid data, all valid days were used to calculate the average [17].

Accelerometer cut-points

The Sasaki vector magnitude 3 cut-points were used to determine time spent in MVPA (≥2690 cpm) [17, 27, 35, 36]. To measure sedentary behaviour, the vector magnitude cut-point was used (< 150 cpm), categorizing light physical activity (LPA) as 150–2689 cpm [17, 27, 35, 37]. These cut-points have not been validated in coronary heart disease participants, although they have been used in prior research in this population [17, 27]. Both of these cut-points have been validated in younger, generally healthy participants [36, 37]. Estimating daily time spent in physical activity and sedentary behavior was calculated by dividing the total time spent (minutes) in each threshold by the number of valid days. In addition, daily time spent in LPA, MVPA and sedentary behavior was expressed as percentage of total daily wear time.

Distribution of physical activity and sedentary behaviour

MVPA bout data used a minimum bout length of 10 min, allowing for 2 min of counts less than the MVPA threshold within this time [17, 27, 35, 36]. Daily time in MVPA bouts was calculated by dividing total time in MVPA bouts by the number of valid days. Sedentary behaviour bout data used a minimum length of 10 min, with no drop time [27]. Sedentary bouts are the number of bouts (≥ 10 consecutive minutes) of sedentary time per day. Average sedentary bout length is the total time in sedentary bouts divided by the total number of bouts. A break is an interruption in sedentary time (≥150 cpm). In the data analysis ‘ignore first sedentary break of each day’ was used to remove sedentary time accrued while the device was removed at night [27].

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), resting blood pressure, and anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS [39]). The HADS questionnaire is a 14-item self-report questionnaire comprised of 4-point Likert-scaled items covering the occurrence of symptoms of anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D) over the past 2 weeks. Each item on the questionnaire is scored from 0 to 3, so that a person can score between 0 (best outcome) and 21 (worst outcome) for either anxiety or depression. The normal range is considered 0–7 on each sub-scale. Sociodemographic and other clinical information, including time since PCI, were also collected.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were completed. Normality of the data was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For parametric data, unpaired t-tests were used, and for the accelerometer data, ANCOVAs were used controlling for accelerometer wear time. For non-parametric data, independent samples Mann–Whitney U test with a 95% confidence interval were used to assess differences between countries. Chi-square analyses were performed to determine if there were significant differences in distribution of categorical data between countries. All analyses were conducted using SPSSFootnote 2 version 25. Significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Results

There was no difference in age, gender or relationship status of participants between countries (Table 1). Swedish participants had a higher level of education and started cardiac rehabilitation later. One third of Australian participants were born in other countries, compared with < 1% of Swedish participants. Australian participants had a higher BMI, a higher proportion of participants with type 2 diabetes and a lower resting DBP. Additionally, Australian participants had higher levels of depression, although both countries had low levels of depression overall.

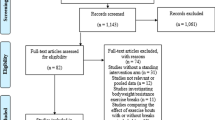

Swedish participants spent a greater proportion of the day in MVPA (p = 0.0001) and LPA (p = 0.045) compared to Australian participants (Fig. 1, Table 2). Swedish participants also spent a significantly smaller proportion of their day in sedentary behaviour (p = 0.001, Fig. 1, Table 2), and completed less sedentary bouts and breaks (Table 2) compared to Australian participants. Between countries, there was no significant difference in the duration of sedentary bouts, with the mean sedentary bout approximately 20 min in length (Table 2). After adjusting for wear time, Swedish participants completed significantly more steps per day compared to Australian participants (Table 2).

Discussion

Following a PCI, Swedish participants were more active and less sedentary than Australian participants commencing cardiac rehabilitation. Although, the minimal difference (approximately 2 min) in sedentary behaviour between both countries is unlikely to be clinically significant. Rogerson et al. (2016) examined the relationship between sedentary behaviour (television viewing time) and all-cause mortality in participants with CVD, and found that the unadjusted mortality rate increased for every one-hour increment in television viewing time [40]. Regardless of this difference, participants in both countries spent a large proportion of their day sitting or lying while awake (63–68%), with approximately 9.5 h per day spent in sedentary behaviour.

A recent meta-analysis of 1 million participants found that too much sedentary behaviour may be above 9-h of device-based sedentary time, with increased mortality risk above this daily amount [41]. Reducing sedentary behaviour has recently been added to the public health physical activity guidelines in Australia and America [42, 43]. Yet, no guidelines for ACS management, or cardiac rehabilitation, appear to include recommendations to reduce sitting time. There is evidence that all-cause mortality decreases with reductions in sedentary behaviour in people with CVD, even when no MVPA is completed [13, 40]. Therefore, decreasing sedentary behaviour may be crucial in ACS patients to prevent recurrent cardiac events, particularly when there is some evidence that nearly half of ACS patients (84% post-PCI) do not exercise at all during weeks 2–5 post-discharge when measured using accelerometry [15], and our results indicate that post-PCI participants are sitting or lying on average 9.5 h per day within 2–3 weeks of their procedure.

The provision of physical activity advice, including referral to cardiac rehabilitation, to individuals with ACS is recommended in Australia and Sweden prior to hospital discharge [3, 5, 32, 33]. Although, the guidelines in Australia are not clear how much physical activity advice should be provided, whether it should include written advice and who should provide the lifestyle counselling. In contrast, Swedish physiotherapists provide physical activity and exercise advice before hospital discharge for approximately 20 to 30-min. Post-PCI patients are recommended to initiate MVPA (versus low-to-moderate physical activity in Australia) as soon as possible after discharge from hospital. It is recognised that it may be challenging to provide physical activity advice prior to discharge, when the average length-of-stay in hospital following a PCI has been reported as 1–2 days [2, 44]. To investigate whether ACS inpatients were receiving lifestyle advice, a large prospective audit of 2299 ACS inpatients in Australian and New Zealand public and private hospitals was conducted in 2012 [45]. This snapshot audit found that only 43% of ACS patients received physical activity advice prior to discharge in these countries. In Sweden, a recent study found that in 78% of the centres surveyed (n = 78), all ACS patients met with a physiotherapist for physical activity and exercise training counselling before discharge [33]. However, only 27% of centers provide written personalized information on lifestyle goals [33]. The difference in education provided between counties prior to discharge may be an explanatory factor for increased levels of physical activity within the Swedish participants at the commencement of cardiac rehabilitation. Further investigation is required of post-PCI physical activity advice prior to discharge to determine who should deliver this information, how much information should be provided and how this information should be delivered, for example, supported by written material. This may have an impact on the patient’s confidence to move upon discharge.

Other possible explanatory factors for the differences in physical activity levels are a lower level of education and a higher proportion of participants born in other countries in the Australian sample, which may have contributed to a lower level of health literacy [46]. Swedish participants also commenced cardiac rehabilitation approximately 6 days later than Australian participants, which may have increased their confidence to move. The statistically significant differences in BMI and diastolic blood pressure may not be clinically significant as both Australian and Swedish participants were overweight, with normal range diastolic blood pressures.

Self-report data suggests that a higher proportion of the Swedish adult population are meeting the physical activity guidelines, that is, 150 min of MVPA per week [34], compared to the Australian adult population [21, 47]. Sixty-seven percent of Swedish adults 18–64 years are sufficiently active compared with 48% of Australians in the same age group. This difference becomes larger when comparing older adults (≥65 years old), with 55% of Swedish older adults meeting the physical activity guidelines compared with 25% of Australian older adults. There are recognised limitations with self-report physical activity data, including over-reporting and differences between surveys [11] but this indicates that Swedish post-PCI participants may have had a higher level of physical activity pre-PCI than the Australian participants and this may partly explain the differences. These differences in pre-existing physical activity levels may be due to a number of factors including the built environment, active transport systems, physical activity promotion in schools, the workplace and the health sector [47, 48]. Some of these factors may also have contributed to an increased physical activity level post-PCI. Despite the differences in general public self-reported physical activity levels, device-based sedentary time in a large sample of Australian (n = 698, mean (SD) age 57.9 (9.9) years) and Swedish adults (n = 851, 56% women, mean (SD) age 66.7 (10.2) years) appears similar (sedentary behaviour A 8.8 vs S 8.2 h per day) [49, 50]. Further investigation of factors that influence patients’ physical activity and sedentary behaviour internationally following a PCI is indicated to contribute to the development of clinical guidelines and the improvement of services. A broader systems approach to physical activity for cardiac health may be indicated, with successful primary prevention strategies potentially contributing to higher baseline physical activity levels and a more readily acceptable need to maintain or increase physical activity levels for secondary prevention of ACS.

Study limitations

This was a small cross-sectional study, providing a snapshot of post-PCI physical activity and sedentary behaviour levels from only one centre in each country, over a similar time frame. There were also less participants in the Australian sample compared to the Swedish sample, which may have led to less conclusive results for this cohort. Generalizability of the results internationally is limited, as the participants were predominantly males, in a relationship and on average, 62 years old. There are limited data on sick leave and whether patients in the two cohorts had returned to work after their PCI. This could have affected the physical activity and sedentary behaviour levels, however, the time for sick leave are similar between countries (1 week). These participants were also potentially more motivated to adhere to lifestyle modifications as they had agreed to participate in cardiac rehabilitation. The Swedish participants may also have been more motivated as they had received some education sessions prior to starting the exercise sessions. The accelerometer cut-off thresholds used may also not have been appropriate for use in the cardiac population, inaccurately classifying physical activity and sedentary behaviour, with no validated methods available for cardiac participants. Additionally, the general time filter applied to the Australian data may have resulted in an over-estimation of sedentary time and decreased wear-time for some participants. Furthermore, the Actigraph monitor may not be the most appropriate monitor to measure sedentary behaviour, with the activPAL monitor considered a more precise monitor for measuring sedentary time [37]. Although, a major strength of this study is the use of the same accelerometers (ActiGraph) and using the same procedures for accelerometer data sampling, cleaning and analysis from post-PCI populations in two countries.

Conclusion

Swedish post-PCI participants when commencing cardiac rehabilitation are more physically active than Australian participants in this study. Potential explanatory factors are differences in post-PCI physical activity education between countries and pre-existing physical activity levels. Despite this, sedentary behaviour is high in both countries. Interventions to address sedentary behaviour are indicated post-PCI, in both the acute setting and cardiac rehabilitation, in addition to traditional physical activity and exercise recommendations. Internationally, further investigation of factors that influence patients’ physical activity and sedentary behaviour following a PCI is indicated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

ActiGraph, Fort Walton Beach, Florida

IBM, Armonk, New York

Abbreviations

- A:

-

Australia

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- LPA:

-

Light physical activity

- MVPA:

-

Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- S:

-

Sweden

References

Byrne RA, Stone GW, Ormiston J, Kastrati A. Coronary balloon angioplasty, stents, and scaffolds. Lancet. 2017;390(10096):781–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31927-X.

AIHW, Davies J. Coronary revascularisation in Australia 2000. Bulletin no.7. AIHW Cat. No. AUS 35. Canberra: AIHW; 2003. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-diseases/coronary-revascularisation-australia-2000/formats.

Chew DP, Scott IA, Cullen L, French JK, Briffa TG, Tideman PA, et al. National Heart Foundation of Australia & Cardiac Society of Australia and new Zealand: Australian clinical guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes 2016. Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25(9):895–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2016.06.789.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. Acute Coronary Syndromes Clinical Care Standard. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2014. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Acute-Coronary-Syndromes-Clinical-Care-Standard.pdf.

Woodruffe S, Neubeck L, Clark RA, Gray K, Ferry C, Finan J, et al. Australian cardiovascular health and rehabilitation association (ACRA) core components of cardiovascular disease secondary prevention and cardiac rehabilitation 2014. Heart Lung Circ. 2015;24(5):430–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2014.12.008.

Piepoli MF, Corra U, Adamopoulos S, Benzer W, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Cupples M, et al. Secondary prevention in the clinical management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. Core components, standards and outcome measures for referral and delivery: a policy statement from the cardiac rehabilitation section of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. Endorsed by the Committee for Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(6e):664–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487312449597.

Anderson L, Thompson DR, Oldridge N, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;1:CD001800. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub3.

Gerber Y, Myers V, Goldbourt U, Benyamini Y, Scheinowitz M, Drory Y. Long-term trajectory of leisure time physical activity and survival after first myocardial infarction: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(2):109–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-010-9523-8.

Apullan FJ, Bourassa MG, Tardif JC, Fortier A, Gayda M, Nigam A. Usefulness of self-reported leisure-time physical activity to predict long-term survival in patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(4):375–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.072.

Ekblom O, Ek A, Cider A, Hambraeus K, Borjesson M. Increased Physical Activity Post-Myocardial Infarction Is Related to Reduced Mortality: Results From the SWEDEHEART Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7(24):e010108. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.010108.

Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-5-56.

Dowd KP, Szeklicki R, Minetto MA, Murphy MH, Polito A, Ghigo E, et al. A systematic literature review of reviews on techniques for physical activity measurement in adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018;15:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0636-2.

van der Ploeg HP, Chey T, Korda RJ, Banks E, Bauman A. Sitting time and all-cause mortality risk in 222 497 Australian adults. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(6):494–500. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2011.2174.

Charman SJ, van Hees VT, Quinn L, Dunford JR, Bawamia B, Veerasamy M, et al. The effect of percutaneous coronary intervention on habitual physical activity in older patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(1):248.

Goodwin AM, Duran AT, Kronish IM, Moise N, Sanchez GJ, Garber CE, et al. Factors associated with objectively measured exercise participation after hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.080.

Ramadi A, Haennel RG. Sedentary behavior and physical activity in cardiac rehabilitation participants. Heart Lung. 2019;48(1):8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.09.008.

ter Hoeve N, Sunamura M, van Geffen ME, Fanchamps MH, Horemans HL, Bussmann JB, et al. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior during cardiac rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98(12):2378–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.05.008.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. A working guide to international comparisons of health. Cat. no. PHE 159. Canberra: AIHW; 2012.

United Nations Development Programme. Human development indices and indicators: 2018 statistical update. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2018.

http://www.oecd.org/. Accessed 29 Nov 2018.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2018. Australia’s health series no. 16. AUS 221. Canberra: AIHW; 2018.

The National Board of Health and Welfare (Sweden). Statistics on causes of death 2019 https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/statistikamnen/dodsorsaker/. Accessed 25 Aug 2019.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cardiovascular disease snapshot 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/heart-stroke-vascular-disease/cardiovascular-health-compendium/contents/hospital-care-for-cardiovascular-disease. Accessed 29 Nov 2018.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Transition between hospital and community care for patients with coronary heart disease: New South Wales and Victoria, 2012–2015. Canberra: AIHW; 2018.

Jernberg T. SWEDEHEART annual report 2018. Matador kommunikation AB; 2018.

Ayabe M, Brubaker PH, Dobrosielski D, Miller HS, Ishi K, Yahiro T, et al. The physical activity patterns of cardiac rehabilitation program participants. J Cardpulm Rehabil. 2004;24(2):80–6.

Prince SA, Blanchard CM, Grace SL, Reid RD. Objectively-measured sedentary time and its association with markers of cardiometabolic health and fitness among cardiac rehabilitation graduates. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(8):818–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487315617101.

Freene N, Del Pozo CB, Davey R. Assessing the ‘active couch potato’ phenomenon in cardiac rehabilitation: rationale and study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1313-x.

Borg S, Öberg B, Nilsson L, Söderlund A, Bäck M. The role of a behavioural medicine intervention in physiotherapy for the effects of rehabilitation outcomes in exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (ECRA) - the study protocol of a randomised, controlled trial. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-017-0557-7.

Freene N, McManus M, Mair T, Tan R, Davey R. Objectively measured changes in physical activity and sedentary behavior in cardiac rehabilitation: a prosepctive cohort study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2018;38(6):E5–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/HCR.0000000000000334.

Freene N, McManus M, Mair T, Tan R, Davey R. High sedentary behaviour and low physical activity levels at 12 months after cardiac rehabilitation: a prospective cohort study. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2019.07.008.

National Heart Foundation of Australia. My heart, my life. 2nd ed: National Heart Foundation of Australia; 2015. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/publications/CON-141.v4_MHML2015_WEB.PDF.

Ögmundsdottir Michelsen H, Sjölin I, Schlyter M, Hagström E, Kiessling A, Henriksson P, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction in Sweden – evaluation of programme characteristics and adherence to European guidelines: The Perfect Cardiac Rehabilitation (Perfect-CR) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27(1):18–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319865729.

World Health Organisation. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: WHO; 2010. http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/.

Migueles JH, Cadenas-Sanchez C, Ekelund U, Delisle Nyström C, Mora-Gonzalez J, Löf M, et al. Accelerometer data collection and processing criteria to assess physical activity and other outcomes: a systematic review and practical considerations. Sports Med. 2017;47(9):1821–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0716-0.

Sasaki JE, John D, Freedson PS, Sasaki JE, John D, Freedson PS. Validation and comparison of ActiGraph activity monitors. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(5):411–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2011.04.003.

Kozey-Keadle S, Libertine A, Lyden K, Staudenmayer J, Freedson PS. Validation of wearable monitors for assessing sedentary behavior. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(8):1561–7. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31820ce174.

What are counts? https://actigraph.desk.com/customer/en/portal/articles/2515580-what-are-counts-. Accessed 29 Nov 2018.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70.

Rogerson MC, Le Grande MR, Dunstan DW, Magliano DJ, Murphy BM, Salmon J, et al. Television viewing time and 13-year mortality in adults with cardiovascular disease: data from the Australian diabetes, obesity and lifestyle study (AusDiab). Heart Lung Circ. 2016;25(8):829–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2016.03.006.

Ku P-W, Steptoe A, Liao Y, Hsueh M-C, Chen L-J. A cut-off of daily sedentary time and all-cause mortality in adults: a meta-regression analysis involving more than 1 million participants. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1062-2.

Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/health-pubhlth-strateg-phys-act-guidelines. Accessed 29 Nov 2018.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/pdf/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf.

Paratz ED, Wilkinson LE, MacIsaac AI. Outcomes of obese and morbidly obese patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(7):785–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2017.08.009.

Redfern J, Hyun K, Chew DP, Astley C, Chow C, Aliprandi-Costa B, et al. Prescription of secondary prevention medications, lifestyle advice, and referral to rehabilitation among acute coronary syndrome inpatients: results from a large prospective audit in Australia and New Zealand. Heart. 2014;100(16):1281–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305296.

World Health Organization. Health literacy: the solid facts. Denmark: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2013. http://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/health-literacy.-the-solid-facts. Accessed 20 Jan 2020.

World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Sweden Physical Activity Factsheet 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/sport/sites/sport/files/physical-activity-factsheets-2018/physical-activity-factsheets-2018/sweden-physical-activity-factsheet-2018_en.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2018.

Onerup A, Arvidsson D, Blomqvist Å, Daxberg E-L, Jivegård L, Jonsdottir IH, et al. Physical activity on prescription in accordance with the Swedish model increases physical activity: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099598.

Healy GN, Winkler EAH, Owen N, Anuradha S, Dunstan DW. Replacing sitting time with standing or stepping: associations with cardio-metabolic risk biomarkers. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(39):2643–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv308.

Dohrn IM, Sjostrom M, Kwak L, Oja P, Hagstromer M. Accelerometer-measured sedentary time and physical activity-a 15 year follow-up of mortality in a Swedish population-based cohort. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(7):702–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.10.035.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants in this study and the staff at the Canberra Hospital, Australia and physiotherapists at Linköping University hospital, Sweden who provided in-kind support, recruiting all participants and collecting baseline data.

Funding

Funding was provided by the University of Canberra (Early Career Academic Research Development Grant) and the ACT Health Chief Allied Health Office (Allied Health Research Support Grant) for the Australian study. For the Swedish study, funding was provided by the Swedish Heart and Lung Association and the Swedish Society for Medical Research. These funding sources had no role in the design of the study; data collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study (NF, SB, MM, TM, RT, RD, BO, MB). NF, SB, MM, TM and MB collected the data. NF and MB analysed the data. All authors interpreted the data (NF, SB, MM, TM, RT, RD, BO, MB). NF and MB drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to, read and approved the final manuscript (NF, SB, MM, TM, RT, RD, BO, MB).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was received from the ACT Health Human Research Ethics Committee, Australia in August 2015 (Project reference: ETH.5.15.076), and the regional ethical review board in Linköping, Sweden in 2015 (Registration number: 2015/209–31) and amendment 2018 (Registration number: 2018/383–32).

Study information including the project aim, data storage and details regarding participant involvement, confidentiality and anonymity were provided at the beginning of the study. All participants provided written consent after reading this information.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Freene, N., Borg, S., McManus, M. et al. Comparison of device-based physical activity and sedentary behaviour following percutaneous coronary intervention in a cohort from Sweden and Australia: a harmonised, exploratory study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 12, 17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-020-00164-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-020-00164-1