Abstract

Background

We aimed to (i) evaluate the immediate effect of a soft knee brace on pain, activity limitations, self-reported knee instability, and self-reported knee confidence, and (ii) to assess the difference in effect between a non-tight and a tight soft brace in patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Methods

Forty-four patients with knee OA and self-reported knee instability participated in the single-session, laboratory, experimental study. A within-subject design was used, comparing a soft brace with no brace, and comparing a non-tight with a tight soft brace. The outcome measures were pain, self-reported knee instability and knee confidence during level and perturbed walking on the treadmill and activity limitations (10-m walk test and the get up and go (GUG) test). Linear mixed-effect model analysis for continuous outcomes and logistic generalized estimating equations for categorical outcomes were used to evaluate the effect of wearing a soft brace.

Results

Wearing a soft brace significantly reduced pain during level walking (B − 0.60, P = 0.001) and perturbed walking (B − 0.80, P < 0.001), reduced the time to complete the 10-m walk (B − 0.23, P < 0.001) and the GUG tests (B − 0.23, P = 0.004), reduced self-reported knee instability during level walking (OR 0.41, P = 0.002) and perturbed walking (OR 0.36, P < 0.001), and reduced lack of confidence in the knees during level walking (OR 0.45, P < 0.001) and perturbed walking (OR 0.56, P < 0.001), compared with not wearing a soft brace. There was no difference in effects between a non-tight and tight brace, except for the 10-m walk test. Wearing a tight brace significantly reduced the time to complete the 10-m walk test in comparison with wearing a non-tight brace (B − 0.11, P = 0.03).

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that a soft brace is an efficacious intervention targeting pain, activity limitations, self-reported knee instability, and knee confidence in the immediate term in patients with knee OA. Further studies are needed evaluating the mode of action based on exerted pressure, and on the generalization to functioning in daily life.

Trial registration

trialregister.nl, NTR6363. Retrospectively registered on 15 May 2017.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Soft braces are elastic, non-adhesive orthoses recommended in the non-surgical management of patients with knee osteoarthritis (OA) [1]. Because of ease of use, lack of complications, and low cost, soft braces are commonly used with the aim of reducing pain and activity limitations [1]. Soft brace efficacy and effectiveness has been assessed in laboratory [2, 3] and ambulatory settings [4, 5]. A laboratory setting allows the assessment of the immediate efficacy of an intervention under controlled conditions, while an ambulatory setting allows the assessment of the effectiveness in real life, where uncontrollable factors may be present. The evidence for immediate efficacy of a soft brace in patients with knee OA is limited. A recent systematic review with meta-analyses on soft bracing in knee OA showed an immediate, moderate improvement in pain when wearing a soft brace [6]. As the results were based on only two studies of low to moderate quality, however, further studies are needed.

It is not well-understood how a soft brace might reduce activity limitations and pain in patients with knee OA. A decrease in pain might be due to sensory stimulation of the skin, leading to a reduction in transmission of pain signals [7]. It is also assumed that a soft brace stimulates cutaneous mechanoreceptors, resulting in improved joint proprioception accuracy, which may have an impact on knee joint stability [2]. Improved knee joint stability might reduce activity limitations [8, 9]. To our knowledge, there is only one study that showed that a soft brace improves self-reported knee instability [3], while the effect of a soft brace on instability-related lack of confidence in the knee [10] is unknown. Externally applied perturbations challenge knee stabilization strategies in patients with knee OA [11, 13]. Perturbed conditions therefore provide a powerful test of soft braces. However, whether a soft brace has an effect on knee stability and knee confidence in perturbed conditions has not been assessed yet. Given the high prevalence of self-reported knee instability and lack of confidence in the knee in patients with knee OA [9, 14], there is a need to study the effect of a soft brace on knee stability and knee confidence during both level and perturbed walk.

Hassan et al. [15] reported that a non-tight soft brace was more effective than a tight brace in reducing pain and improving postural sway in patients with knee OA. The authors suggested that a non-tight brace provides more recurrent stimuli to cutaneous mechanoreceptors, whereas a tight brace provides constant pressure, to which skin mechanoreceptors adapt [15]. There is a clear need to replicate this study in order to determine whether the level of tightness has an effect on activity limitations, knee stability and knee confidence.

The currently available evidence for the use of soft braces in patients with knee OA is limited and of low quality. Thus, the aims of the study were to (i) evaluate the immediate effect of a soft brace on pain, activity limitations, and self-reported knee instability and knee confidence, and to (ii) assess the difference in effect between a non-tight and a tight soft brace in patients with knee OA. We hypothesized that (i) a soft brace reduces pain, activity limitations, and self-reported knee instability, and improves knee confidence, and that (ii) a non-tight soft brace has a greater effect than a tight soft brace.

Methods

Trial design

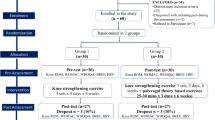

In this single-session, laboratory, experimental study, a within-subject design was used, comparing a soft brace with no soft brace, and comparing a non-tight with a tight soft brace. The order of the non-tight and tight brace was randomized, using a computer generated random sequence made prior to the study. All participants were blinded to the type of brace (non-tight or tight).

Participants

Participants were recruited from the Amsterdam Osteoarthritis (AMS-OA) cohort through telephone-based screening between August 2015 and April 2016. The AMS-OA cohort consists of participants with established knee and/or hip OA according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria [16], who had been referred to an outpatient rehabilitation center (Reade, Center for Rehabilitation and Rheumatology, Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Participants were assessed by rheumatologists, radiologists, and rehabilitation physicians. According to the ACR criteria, knee OA is diagnosed if knee pain is present and three of the following six parameters are present: age > 50 years, morning stiffness < 30 minutes, crepitus, bony tenderness, bony enlargement and no palpable warmth. The inclusion criteria for the present study were (i) diagnosis of bilateral or unilateral knee OA according to the ACR criteria [16], (ii) age between 50 and 80 years, and (iii) presence of self-reported knee instability in the past 3 months. Self-reported knee instability was defined as at least one episode of buckling, shifting, or giving way of the knee in the last three months, reported by participants [17].

The exclusion criteria for the AMS-OA cohort were total knee replacement and/or inflammatory arthritis (including rheumatoid arthritis, crystal arthropathy, septic arthritis, and spondylarthropathy). Additional exclusion criteria for the present study were (i) radiographic patello-femoral (PF) joint OA (PFOA), and (ii) presence of comorbidity resulting in severe activity limitations. The soft brace in the current study did not involve patellar opening, thus, to avoid applying pressure on the PF compartment, we excluded patients with PFOA.

Interventions

A commercially available soft brace (GENUTEX A2, Human I; Bleiswijk, The Netherlands) was used. The following sizes of the soft brace were available: S: 30–35 cm, M: 35–40 cm, L: 40–45 cm, XL: 45–50 cm, and XXL: 50–55 cm. These sizes were used to differentiate between a non-tight and tight soft brace. A tight brace was defined as one fitted based on shank and thigh circumferences measured according to instructions provided by the distributor. A non-tight brace was defined as one a size larger than a tight brace. Fitting and positioning of the brace were performed by a trained investigator (TC) according to instructions provided by the distributor. Both knees were braced regardless of the knee OA status. Participants were allowed to become accustomed to the brace before treadmill walking. Participants were blinded to the type of brace by informing them that the study was a comparison of two different braces, without mentioning differences in tightness. Braces were identical in appearance.

Primary outcome measure

Pain

Knee pain during walking on the treadmill was assessed using the Dutch-translated 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS) (0–10), with higher scores representing more pain [18]. The following question was asked during both level and perturbed walking: “On a scale from 0 to 10, how would you score the level of your left/right knee pain while walking on the treadmill?” The Dutch translated NRS has been frequently used in the Netherlands [17, 19, 20].

Secondary outcome measures

Activity limitations

Activity limitations were assessed with two standardized physical performance tests: the 10-m walk test [21] and the get up and go (GUG) test [22]. The 10-m walk test assesses the time to walk a distance of 10 m along a level and unobstructed corridor [21]. Participants were instructed to walk as fast as possible and timed with a stopwatch. The GUG test measures the time a person takes to get up from a chair and walk 15 m as fast as possible along a level and unobstructed corridor [23]. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the GUG test is 0.98 for intra-tester reliability and 0.98 for inter-tester reliability [22].

Self-reported knee instability

Self-reported knee instability was assessed with the Dutch version of the questionnaire developed by Irrgang et al. [24]. Self-reported knee instability was assessed with a question on the number of episodes during walking on the treadmill of perceived buckling, shifting, or giving way, separately for the right and left knee. The following question was asked during both level and perturbed walking: “How many times have you had a sensation of left/right knee buckling, shifting, or giving way while walking on the treadmill?” Self-reported knee instability was dichotomized into no episode of knee instability versus one or more episodes of knee instability. The translated Dutch version of the questionnaire has been previously used by our research group [20, 25].

Self-reported knee confidence

Knee confidence was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale (not at all, mildly, moderately, severely, and extremely) in response to the question asked during both level and perturbed walking: “How much were you troubled with lack of confidence in your left/right knee while walking on the treadmill?” This is a single item from the Dutch-validated Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) [26,27,28]. Self-reported knee confidence was dichotomized into lack (mildly, moderately, severely, or extremely troubled) versus full (not troubled at all) knee confidence.

Other measures

Participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded prior to testing and included: age, gender, duration of symptoms, body-mass index (BMI), knee OA radiographic severity, and muscle strength. BMI was calculated as body mass in kilograms divided by height in square meters. The Kellgren and Lawrence score (KL score) from the more severely affected knee was used to assess the radiographic severity of the disease [29]. Conventional radiographs of tibiofemoral joints were made by a weight-bearing posterior-anterior view according to Buckland-Wright et al. [30]. Two independent observers graded radiographs: a bone and joint radiologist and an epidemiologist trained by two musculoskeletal radiologists. Muscle strength (in Newton meters per kilogram of body weight (Nm/kg)) was assessed for flexion and extension of the knee using an isokinetic dynamometer (Humac Norm, CSMi, Boston, USA) according to a previously described protocol [11]. The mean strength of the quadriceps and hamstring muscles of the left and right knee was reported. The Dutch translation of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) was used to assess self-reported knee pain, stiffness, and activity limitations of the most affected knee [12, 13].

Sample size

The study was powered on self-reported pain. An expected effect size of 0.5 was calculated from the change in pain and its confidence interval reported in the study of Hassan et al. [15]. With effect size = 0.5, alpha = 0.05, power (1-β) = 0.80, and a two-sided test, the minimum number of subjects required was n = 33. Allowing for an attrition rate of 10% during the course of the study [31], this study needed to include at least 36 patients.

Procedure

The study procedure is presented in Table 1. Participants of the study attended a single testing session. Outcome measures, with the exception of the 10-m walk and GUG tests, were assessed on the treadmill, which is integrated into the GRAIL system. The GRAIL system is made up of a treadmill with a dual belt, placed in a virtual reality environment (GRAIL system, MOTEKForce Link, The Netherlands). Walking on the treadmill was initially performed with no brace. Patients had a familiarization session on the treadmill lasting at least one minute, during which walking speed was determined. They were instructed to walk at a comfortable, self-selected pace while shod and wearing a safety harness. Following the familiarization session, participants were subjected to two tasks (without wearing a brace): (i) level walking for 2 minutes and (ii) walking with mechanical perturbations on the treadmill. Mechanical perturbations on the treadmill comprised five lateral-medial translations (2 cm displacements) of the treadmill belts during the stance phase of a gait cycle. For safety reasons, participants were informed about mechanical perturbations in advance. The mechanical perturbations of the treadmill occurred at random moments. Immediately following each of the two tasks, participants reported their average levels of knee pain, number of knee instability episodes, and perceived knee confidence. Subsequently, participants were randomized to receive a non-tight or tight brace and the two tasks were repeated while wearing a brace. Prior to testing on the treadmill, the 10-m walk and GUG tests were performed without the brace. Following testing on the treadmill, the 10-m walk and GUG tests were repeated with the brace (non-tight or tight).

After a 30-minute rest, the procedure crossed over to the second part of the assessments but with another type of soft brace (tight or non-tight). By counterbalancing the order of the type of brace we controlled the potential confounding effect of fatigue and learning effects on the comparison between a non-tight versus tight brace.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Numbers (percentages) were used for categorical variables, and means (SD) for continuous variables. Prior to the statistical analysis, outcome measures were checked for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. Pain and self-reported knee instability and knee confidence were obtained for each knee separately (knee-level variable), and data from both knees were used in the statistical analysis. Data on the 10-m walk and GUG tests were analyzed as person-level variables. Four comparisons were analyzed: (i) brace versus no brace, (ii) tight brace versus no brace (i.e., baseline before tight), (iii) non-tight brace versus no brace (i.e., baseline before non-tight), and (iv) non-tight brace versus tight brace. Linear mixed-effect model analysis for repeated measurements within participants was used for continuous outcome measures (pain, 10-m walk test, GUG test). Logistic generalized estimating equations (GEE) analysis with an exchangeable working correlation matrix was used for dichotomous outcome measures (self-reported knee instability and knee confidence). No covariates were included in the models, because addition of a covariate to a repeated measures analysis does not alter the main effects of a within-subject factor (e.g., age, gender, etc. are the same at each data point) [32]. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

There were 214 persons from the AMS-OA cohort initially contacted for eligibility; 144 persons declined to participate and 26 did not meet the inclusion criteria for the following reasons: absence of self-reported knee instability in the last 3 months (n = 13), comorbidity severely affecting daily functioning (n = 8), or age not between 50 and 80 years (n = 5). In total, 44 patients with knee OA and self-reported knee instability participated in the study. Demographics and clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 2. The participants had a mean ± SD age of 65.7 ± 9.3 years, a mean ± SD BMI of 29.8 ± 5.5 kg/m2, and 29 (65.9%) were women.

Descriptive data on pain and activity limitations by the conditions are presented in Table 3. The results of the statistical evaluation of the outcomes are presented in Table 4. Wearing a soft brace significantly reduced pain during level walking (B − 0.60, P = 0.001) and perturbed walking (B − 0.80, P < 0.001), reduced the time to complete the 10-m walk test (B − 0.23, P < 0.001) and GUG test (B − 0.23, P = 0.004), reduced self-reported knee instability during level walking (OR 0.41, P = 0.002) and perturbed walking (OR 0.36, P < 0.001), and reduced lack of confidence in the knees during level walking (OR 0.45, P < 0.001) and perturbed walking (OR 0.56, P < 0.001), compared with not wearing a soft brace (Table 4, column 2).

Whether the brace was non-tight or tight, the effects were similar (Table 4, columns 3 and 4). There was no difference in effects between a non-tight and tight brace, except for the 10-m walk test. Wearing a tight brace significantly reduced the time to complete the 10-m walk test in comparison with wearing a non-tight brace (B − 0.11, P = 0.03) (Table 4, column 5).

To determine whether the beneficial effects were in most participants or predominantly due to large effects in a few, the effect of wearing a soft brace on the outcome measures has been calculated per individual and presented on the histograms. The distribution of the individual effects per outcomes was fairly normal indicating that the overall beneficial effects are not attributable to large effects in a few participants [33].

Discussion

In this study, we found that a soft brace reduced activity limitations and pain, and improved self-reported knee stability and knee confidence in patients with knee OA. We did not find significant differences between a non-tight and a tight brace, with the exception of performing the 10-m walk test. The results support the use of a soft brace as an efficacious treatment option in the immediate management of patients with knee OA.

This is the first high-quality study reporting on the immediate effect of wearing a soft brace, on pain, activity limitations, and self-reported knee instability, and knee confidence in patients with knee OA. The results of the recent systematic review on soft bracing in knee OA [6] showed that the quality of previous studies [2, 3, 15] ranged from low [3, 15] to fair [2] according to the Downs and Black scale [34]. If our study is scored according to the same criteria [34], the study is scored as a good-quality study (i.e., study quality percentage 68%). Compared to previous studies, our study received a higher score in the Downs and Black scale in statistical analysis, representativeness of the study population, and reporting on the facilities where patients were assessed.

The size of the effect on pain in our study is comparable to those observed in previous studies [2, 3, 15]. Bryk et al. [2] observed a 0.6 mm reduction in the visual analog scale (VAS) for pain during the Stair Climb Power Test (SCPT), while Schween et al. [3] and Hassan et al. [15] reported a similar decrease in the VAS for pain during level walking. We observed a 0.6-point (95% CI −0.97–0.23) and 0.8-point (95% CI −1.11–0.43) decrease in pain on the NRS for level and perturbed walking, respectively. This effect is close to the 1-point threshold for the minimal clinically important difference for NRS pain [35].

To our knowledge, only Bryk et al. [2] used performance-based physical tests to evaluate the immediate effect of a soft brace on activity limitations in patients with knee OA. Our study confirms their findings [2]. We found that wearing a soft brace significantly reduced time to complete both the 10-m walk and GUG tests by 0.23 s (95% CI −0.31–0.13 and −0.38–0.07, respectively). In the absence of information on the minimal clinically important change in these measures, the clinical relevance of these effects cannot be evaluated. Furthermore, these effects should be viewed in the light of this being a laboratory-based study and the short duration of brace use. Further research on generalization to functioning in daily life and the clinical relevance of these effects in daily life is indicated.

Previously, only one study had observed that a soft brace improved self-reported knee instability [3], while the effect on knee confidence had not been studied before. The present study confirms that a soft brace improves self-reported knee stability, and is the first study to show that a soft brace improved confidence in the knees, in patients with knee OA. These results are noteworthy, given that self-reported knee instability has been reported in the majority (>60%) of patients with knee OA [9, 14], and that it may affect their quality of life [9, 25]. Knee confidence may influence decisions about participation in physical activity. Lack of confidence may force patients with knee OA to alter their daily activities, to avoid knee buckling and pain [36]. A soft brace may therefore indirectly influence daily activities via the improvement of knee instability and knee confidence.

This is the first study using external perturbations on the treadmill to evaluate the effect of a soft brace on pain, and on self-reported knee instability and knee confidence. External perturbations provide a more stimulating and challenging environment for knee stability [37], and simulate situations in which patients might experience increased knee instability and lack of confidence. Knee OA could affect the ability of the neuromuscular system to execute appropriate commands in response to external challenges, resulting in joint instability [37]. It is therefore important to show that, even when participants were subjected to external perturbations, the effect of wearing a soft brace on pain and self-reported knee instability and knee confidence continued.

The second aim of this study was to assess the difference in effect between a non-tight and a tight brace. We hypothesized that a non-tight brace would elicit stronger effects than a tight brace. This hypothesis was based on a study reporting that a non-tight brace reduced pain and improved postural sway more than a tight brace [15]. Hassan et al. [15] speculated that a non-tight brace provided more recurrent stimuli, by allowing movement between the brace and the skin, and thus elicited continuous response from cutaneous receptors. By contrast, a tight brace might provide constant pressure, to which skin mechanoreceptors adapt. Our hypothesis was not confirmed. Differences in the type of the brace may be an explanation. Hassan et al. [15] used a tubigrip elastic bandage, whereas we used a soft brace specifically designed for the knee joint. More importantly, we are unaware whether the level of pressure exerted on the skin by our soft brace was comparable to that used by Hassan et al. [15]. There is therefore a need to develop a reliable and valid measure of tightness.

Because a soft brace is an efficacious intervention, there is a need to understand the mechanisms underlying the effect. Soft braces might reduce self-reported knee instability by altering proprioceptive feedback [15] and enhancing muscle activity [38]. Mild compression provided by a soft brace [2, 39] might result in an improved sense of joint stability and greater confidence in the knee joint [10]. It has been suggested that soft braces reduce joint contact forces, due to less muscle co-contraction [3, 40]. Another mechanism could be an increase in skin temperature [39, 40]. Heat therapies are widely used in clinical practice to obtain analgesia, decrease muscle spasm, and encourage regional blood flow [41]. Thus, a soft brace, by providing warmth to the skin, may lead to less muscle contracture and therefore to reduced knee joint compressive forces. Finally, a placebo effect is a mechanism that should be considered [4, 42]. To better understand how soft braces work in knee OA, studies exploring the potential mechanisms underlying the observed effects are warranted.

Some limitations should be acknowledged. First, it was not possible to blind participants to the brace; however, it should be noted that blinding to the intervention in this type of studies is generally not possible. Second, our study provided information on effect in the laboratory. Thus, we do not know whether the observed effects can be generalized to the daily life of patients with knee OA. In light of limited evidence in this area, this should be a priority for future research in order to determine whether wearing a soft brace has long-term effects in daily life in patients with knee OA. Finally, assessment of the outcomes was performed first without a brace and then with a brace. This order may have led to bias because of possible learning effects.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that a soft brace is an efficacious intervention, targeting pain, activity limitations, and self-reported knee instability and knee confidence in the immediate-term in patients with knee OA. Although the results can potentially impact clinical practice, we acknowledge that studies on the generalization to functioning in daily life are required to support a soft brace as an established treatment option.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- AMS-OA:

-

Amsterdam Osteoarthritis cohort

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GEE:

-

Generalized estimating equations analysis

- GUG:

-

Get up and go test

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- K&L:

-

Kellgren & Lawrence

- KL:

-

Kellgren–Lawrence score

- KOOS:

-

Knee Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

- NRS:

-

Numeric rating scale

- OA:

-

Osteoarthritis

- PFOA:

-

Patello-femoral joint osteoarthritis

- ROA:

-

Radiographic knee osteoarthritis

- SCI:

-

Self-reported knee confidence

- SCPT:

-

Stair Climb Power Test

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SKI:

-

Self-reported knee instability

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

References

Beaudreuil J, Bendaya S, Faucher M, Coudeyre E, Ribinik P, Revel M, Rannou F. Clinical practice guidelines for rest orthosis, knee sleeves, and unloading knee braces in knee osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76:629–36.

Bryk FF, Jesus JF, Fukuda TY, Moreira EG, Marcondes FB, Santos MG. Immediate effect of the elastic knee sleeve use on individuals with osteoarthritis. Rev Bras Reumatol. 2011;51:440–6.

Schween R, Gehring D, Gollhofer A. Immediate effects of an elastic knee sleeve on frontal plane gait biomechanics in knee osteoarthritis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115782.

Berry H, Black C, Fernandes L, Berstein RM, Whittington J. Controlled trial of a knee support (‘Genutrain') in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Eur J Rheumatol Inflamm. 1992;12:30–4.

Callaghan MJ, Parkes MJ, Hutchinson CE, Gait AD, Forsythe LM, Marjanovic EJ, Lunt M, Felson DT. A randomised trial of a brace for patellofemoral osteoarthritis targeting knee pain and bone marrow lesions. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1164–70.

Cudejko T, van der Esch M, van der Leeden M, Roorda LD, Pallari J, Bennell KL, Lund H, Dekker J. Effect of soft braces on pain and physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analyses. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2017.04.029.

Hall JE. Somatic sensation: I. General organisation; the tactile and position senses. In: Guyton AC, editor. Textbook of medical physiology. Philadelphia: PA: Saunders; 1996. p. 595–607.

Schmitt LC, Fitzgerald GK, Reisman AS, Rudolph KS. Instability, laxity, and physical function in patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. Phys Ther. 2008;88:1506–16.

van der Esch M, Knoop J, van der Leeden M, Voorneman R, Gerritsen M, Reiding D, Romviel S, Knol DL, Lems WF, Dekker J, Roorda LD. Self-reported knee instability and activity limitations in patients with knee osteoarthritis: results of the Amsterdam osteoarthritis cohort. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:1505–10.

Skou ST, Wrigley TV, Metcalf BR, Hinman RS, Bennell KL. Association of knee confidence with pain, knee instability, muscle strength, and dynamic varus-valgus joint motion in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:695–701.

van der Esch M, Steultjens M, Harlaar J, Knol D, Lems W, Dekker J. Joint proprioception, muscle strength, and functional ability in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:787–93.

Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–40.

Roorda LD, Jones CA, Waltz M, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM, van der Eijken JW, Willems WJ, Heyligers IC, Voaklander DC, Kelly KD, Suarez-Almazor ME. Satisfactory cross cultural equivalence of the Dutch WOMAC in patients with hip osteoarthritis waiting for arthroplasty. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:36–42.

Fitzgerald GK, Piva SR, Irrgang JJ. Reports of joint instability in knee osteoarthritis: its prevalence and relationship to physical function. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:941–6.

Hassan BS, Mockett S, Doherty M. Influence of elastic bandage on knee pain, proprioception, and postural sway in subjects with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:24–8.

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–49.

Knoop J, Dekker J, van der Leeden M, van der Esch M, Thorstensson CA, Gerritsen M, Voorneman RE, Peter WF, de RM, Romviel S, Lems WF, Roorda LD, Steultjens MP. Knee joint stabilization therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized, controlled trial. Osteoarthritis Cartil. 2013;21:1025–34.

Cruz-Almeida Y, King CD, Goodin BR, Sibille KT, Glover TL, Riley JL, Sotolongo A, Herbert MS, Schmidt J, Fessler BJ, Redden DT, Staud R, Bradley LA, Fillingim RB. Psychological profiles and pain characteristics of older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:1786–94.

Holla JF, Steultjens MP, Roorda LD, Heymans MW, Ten WS, Dekker J. Prognostic factors for the two-year course of activity limitations in early osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:1415–25.

van der Esch M, van der Leeden M, Roorda LD, Lems WF, Dekker J. Predictors of self-reported knee instability among patients with knee osteoarthritis: results of the Amsterdam osteoarthritis cohort. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:3007–13.

Lin YC, Davey RC, Cochrane T. Tests for physical function of the elderly with knee and hip osteoarthritis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;11:280–6.

Piva SR, Fitzgerald GK, Irrgang JJ, Bouzubar F, Starz TW. Get up and go test in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:284–9.

Hurley MV, Scott DL, Rees J, Newham DJ. Sensorimotor changes and functional performance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997;56:641–8.

Irrgang JJ, Snyder-Mackler L, Wainner RS, Fu FH, Harner CD. Development of a patient-reported measure of function of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1132–45.

Knoop J, van der Leeden M, van der Esch M, Thorstensson CA, Gerritsen M, Voorneman RE, Lems WF, Roorda LD, Dekker J, Steultjens MP. Association of lower muscle strength with self-reported knee instability in osteoarthritis of the knee: results from the Amsterdam Osteoarthritis cohort. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:38–45.

Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD. Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)–development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;28:88–96.

Roos EM, Toksvig-Larsen S. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) - validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:17.

de Groot IB, Favejee MM, Reijman M, Verhaar JA, Terwee CB. The Dutch version of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score: a validation study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:16.

Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502.

Buckland-Wright JC, Macfarlane DG, Jasani MK, Lynch JA. Quantitative microfocal radiographic assessment of osteoarthritis of the knee from weight bearing tunnel and semiflexed standing views. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:1734–41.

Hewitt C, Hahn S, Torgerson DJ, Watson J, Bland JM. Adequacy and reporting of allocation concealment: review of recent trials published in four general medical journals. BMJ. 2005;330:1057–8.

Seltman J. Experimental Design and Analysis. 2015. http://www.stat.cmu.edu/~hseltman/309/Book/Book.pdf. Accessed 15 Apr 2017.

Twisk JW. Applied longitudinal data analysis for epidemiology. Cambridge: England, Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84.

Salaffi F, Stancati A, Silvestri CA, Ciapetti A, Grassi W. Minimal clinically important changes in chronic musculoskeletal pain intensity measured on a numerical rating scale. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:283–91.

Sharma L, Chmiel JS, Almagor O, Moisio K, Chang AH, Belisle L, Zhang Y, Hayes KW. Knee instability and basic and advanced function decline in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:1095–102.

Kumar D, Swanik CB, Reisman DS, Rudolph KS. Individuals with medial knee osteoarthritis show neuromuscular adaptation when perturbed during walking despite functional and structural impairments. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;116:13–23.

Collins A, Blackburn JT, Olcott C, Yu B, Weinhold P. The impact of stochastic resonance electrical stimulation and knee sleeve on impulsive loading and muscle co-contraction during gait in knee osteoarthritis. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2011;26:853–8.

Chuang SH, Huang MH, Chen TW, Weng MC, Liu CW, Chen CH. Effect of knee sleeve on static and dynamic balance in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2007;23:405–11.

Mazzuca SA, Page MC, Meldrum RD, Brandt KD, Petty-Saphon S. Pilot study of the effects of a heat-retaining knee sleeve on joint pain, stiffness, and function in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:716–21.

Brosseau L, Yonge KA, Robinson V, Marchand S, Judd M, Wells G, Tugwell P. Thermotherapy for treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD004522.

Pajareya K, Chadchavalpanichaya N, Timdang S. Effectiveness of an elastic knee sleeve for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized single-blinded controlled trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86:535–42.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank Djody van Swaal, from Centrum Orthopedie Rotterdam, for providing the soft braces. We gratefully acknowledge Marjolein Booij, MSc, Linda van Gardner, MSc, and Anke Hofste, MSc, for their help during data collection. We thank Johannes Gijsbers, PhD for his help in the development of the application for treadmill perturbations.

Funding

This work was supported by the European Union, Seventh Framework Programme, under grant agreement number 607510. The European Union did not contribute to the design, interpretation of data, drafting, and final approval of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: TC, MvdE, and JD. Acquisition of data: TC, MvdE, and JD. Analysis and interpretation of data; TC, MvdE, MvdL, JvdN, LR, WL, JT, MS, JW, JH, and JD. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: TC, MvdE, MvdL, JvdN, LR, WL, JT, MS, JW, JH, and JD. Final approval of the version of the article to be published: TC, MvdE, MvdL, JvdN, LR, WL, JT, MS, JW, JH, and JD.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval was obtained from the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center Amsterdam. Data extraction from the AMS-OA cohort was approved by the Slotervaart Hospital/Reade Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Cudejko, T., van der Esch, M., van der Leeden, M. et al. The immediate effect of a soft knee brace on pain, activity limitations, self-reported knee instability, and self-reported knee confidence in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 19, 260 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1456-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-017-1456-0