Abstract

Background

Intestinal schistosomiasis is still a public health problem in Burundi. Since 2008, annual mass drug administration with praziquantel has been rolled out in 11 endemic districts. The national programme relies on school-based surveys with kato-katz to monitor the impact of mass drug administration. We explored whether routine data on intestinal schistosomiasis as determined by direct fecal smears at health centre level could be used.

Methods

From the Burundian National Health Information System, we collected routine incidence data on intestinal schistosomiasis as determined by direct smear examination in all 45 sanitary districts during 2011–2015. A temporal trends analysis was performed using a mixed negative binomial regression. Sanitary districts with mass drug administration campaigns with praziquantel (n = 11) were compared with those without (n = 34). In addition, prevalence data on intestinal schistosomiasis based on kato-katz results from a school-based national mapping in 2014 were compared with the incidence data in health centres based on direct smear results, in the same 45 sanitary districts.

Results

In the 11 sanitary districts applying mass drug administration with praziquantel, the incidence rate decreased significantly for the years 2014 (β2014 = − 0.826, P = 0.010) and 2015 (β2015 = − 1.294, P < 0.001) and for the five-year period (β = − 0.286, P < 0.001), whereas in the 34 districts where mass drug administration was not delivered, there was no significant decrease over time (β = − 0.087, P = 0.219). In most of the 45 sanitary districts, the low prevalence based on kato-katz in school children was confirmed by low incidence rates based on direct smears in the health centres.

Conclusions

National Health Information System surveillance data, based on routinely collected direct smear results at health centre level, may be able to monitor the impact of mass drug administration with praziquantel on intestinal schistosomiasis in Burundi. Control and elimination of intestinal schistosomiasis call for integration of adequate diagnosis and treatment into routine activities of primary health care facilities, as recommended by the World Health Organization since more than 20 years. When moving towards elimination, more sensitive tests, such as the point-of-care circulating cathodic antigen assay are desirable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Schistosomiasis is a parasitic disease caused by the genus Schistosoma [1, 2]. It is one of the neglected tropical diseases (NTD). Linked to poverty, schistosomiasis is more prevalent in countries and regions where hygienic conditions are precarious and access to safe water and adequate sanitation is limited [2]. Between 200–250 million of people in the world are infected [3] and 600–780 million are at risk [3, 4]. The sub-Saharan African countries are the most affected by this disease, with more than 90% of the total burden [5, 6].

In Burundi, intestinal schistosomiasis has been a public health challenge for many decades [7, 8]. According to a nationwide school-based survey performed in 2007, based on the kato-katz (KK) test [9], 11 out of the 45 sanitary districts (SD) in Burundi were considered at risk of intestinal schistosomiasis. Since 2008, these 11 SD have been targeted for annual mass drug administration (MDA) with praziquantel (PZQ) to school-aged children between 5 and 15 years-old.

To measure the impact of MDA, epidemiological surveys using KK test were performed in a number of primary schools, chosen as sentinel sites [10]. These surveys demonstrated a decrease in S. mansoni infection from 12.7% in 2007 (baseline) to 1.1% in 2011 [10].

After six years of annual MDA in the targeted areas, a school-based national mapping was implemented to reassess the extent of the schistosomiasis problem and to determine whether it was possible to move to the elimination phase [10]. The results from the KK test showed that there was a decline in the prevalence of infection, from 12.7% in 2007 (baseline) to 2.2% in 2014 [10].

Although the epidemiological surveys in sentinel sites and the national mapping provide a good estimation of the prevalence of schistosomiasis, it is a very laborious and costly undertaking [11, 12] and often requires external financial support, especially in resource-limited countries such as Burundi [9, 10]. It is therefore important to look for other cost-effective and sustainable strategies to monitor the impact of MDA campaigns.

In this paper, we aim to evaluate whether routine data on intestinal schistosomiasis as determined by direct smear (DS) stool examination and reported by health centres (HC) to the Directorate of National Health Information System (DNHIS), could be used as an approach to monitor the impact of MDA on intestinal schistosomiasis in Burundi.

Methods

Data on the study area and population

Burundi is an East African country. It is limited (i) in the north by Kanyaru River and Cohoha Lake, which separate it from Rwanda, (ii) in the east and southeast by Malagarazi River and Tanganyika Lake, respectively, which separate it from Tanzania, and (iii) in the west and northwest by Tanganyika Lake and Rusizi River, respectively, which separate it from Democratic Republic of Congo.

From 2011 to 2015 (the period of this study), Burundi had 17 sanitary provinces (SP) and 45 SD. The number of HC increased from 284 in 2011 to 355 in 2015 in the 11 SD considered at risk of intestinal schistosomiasis, and from 528 in 2011 to 643 in 2015 in the remaining 34 SD.

All the 11 SD considered at risk of intestinal schistosomiasis, and targeted by MDA campaigns with PZQ, are located near great rivers (the Kanyaru and Rusizi rivers in the north and northwest, respectively) and lakes (Lake Cohoha in the north and Lake Tanganyika in the west, south and southeast), which separate Burundi from neighbouring countries. This is not the case for the 34 remaining SD, which are mainly located far from the borders.

The average population per SD was 192,166 in 2011 and 211,298 in 2015. The average population density was 311 per km2 in 2011 and 342 per km2 in 2015.

Functioning of the National Health Information System

The Burundian National Health Information System (NHIS) consists of three levels: the peripheral level (SD) with HC and district hospitals (DH); the intermediate level (SP) with regional hospitals; and the central level (DNHIS) with national and specialised hospitals. Routine data on diseases registered in consultations and laboratory (e.g. malaria, diarrhoea, schistosomiasis) are collected from each HC and reported to the SD, which reports in turn to the SP and the SP reports to the DNHIS. For hospitals, they report to the SD or to the SP or to the DNHIS, according to the level they belong to. Reporting is done monthly for more than 95% of diseases, including intestinal schistosomiasis.

Data collection

In 2017, routine data on intestinal schistosomiasis were collected from the DNHIS. The data concerned all intestinal schistosomiasis cases as determined by DS and reported by the HC from each SD during the period 2011 to 2015. They were used for this study with the authorisation of the Ministry of Health. Data from hospitals were not collected to avoid duplicates as hospitals receive patients referred by HC.

Data analysis

We described the number of reported cases based on DS detection per year in each SD over a period of 5 years, with a focus on 2014, where the DS-based incidence at HC level could be compared with the KK-based prevalence in school children.

We analysed temporal trends in intestinal schistosomiasis incident cases for each year in the 11 SD targeted by MDA campaigns (zone of intervention-ZI) with PZQ, and compared them with those in the 34 remaining SD (zone of non-intervention-ZNI), to allow for any general trend in intestinal schistosomiasis, not related to annual MDA by PZQ.

The number of intestinal schistosomiasis cases reported each year were put on a logarithmic scale. The slope should be linear if the incidence remained identical, despite the progressive growth of the population at risk (assumed to be identical for all SD, after the general census of 2008). The effect of MDA campaigns on the annual incidence of intestinal schistosomiasis should manifest itself as a significant change in the slope.

A mixed negative binomial regression was performed due to the overdispersion of the data [13, 14]. A random effect was added to take into account the existing correlation in the data per district over time. The trends of the number of intestinal schistosomiasis cases reported each year were compared between ZI and ZNI. The respective slopes βi, i = 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, were estimated to compare the trends in ZI and ZNI each year (2012, 2013, 2014 and 2015) to the reference year 2011. A second analysis was performed, for which only one slope β was estimated to study the overall trend during the period of 5 years (from 2011 to 2015). The slope estimation was given for both zones ZI and ZNI. Stata version 12 (Stata Corp. LP, College Station, USA) software was used to calculate the slopes with an α risk error of 5%.

Results

The routine data obtained by DS showed a decreasing schistosomiasis incidence rate in the majority of the SD in the ZI, and a stable incidence rate in the majority of the SD in the ZNI. However, there were some exceptions in both zones. In the ZI, the incidence rate in the SD of Rumonge remained stable over time and in the ZNI, the incidence rates in some of the SD decreased, while they increased in others (Table 1).

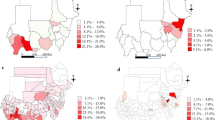

We were able to compare the data of 2014 (Fig. 1) where both district-wide routine surveillance data and school-based mapping data were available. In most SD the low prevalence was confirmed by a low incidence rate. However, in some SD (e.g. Bururi, Gitega, Musema, Zone Centre) the prevalence rate was zero, while routine surveillance detected some cases. The two districts with the highest prevalences also showed the highest incidence rates, but relatively high incidence rates were also seen in SD with lower prevalences.

Table 2 shows the results of the temporal trends analysis. Both in the ZI and the ZNI, the incidence rate decreased, but this only reached significance in the ZI for 2014 (β2014 = − 0.826, P = 0.010) and 2015 (β2015 = − 1.294, P < 0.001). The overall trend over the five years period (2011 to 2015) showed a highly significant decrease in the ZI (β = − 0.286, P < 0.001), while no significant trend was observed in the ZNI (β = − 0.087, P = 0.219) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

MDA campaigns with PZQ are recommended for the control of schistosomiasis [15,16,17] and constitute the current national strategy for schistosomiasis control in Burundi [18]. The KK test is still the primary diagnostic tool in monitoring the impact of national school-based deworming programmes on S. mansoni infection [15, 17], but it is not available in Burundi as a routine test at PHC level. The only test available for the diagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis in Burundian HC is the DS [18]. We explored whether DS results that are routinely collected at HC level could give an indication of the impact of MDA with praziquantel on S. mansoni infection in Burundi as well. We did this by comparing temporal trends in intestinal schistosomiasis as determined by DS in HC of ZI with those in ZNI. A decreasing trend was observed in the ZI, but not in the ZNI. The decreasing trend in the ZI was in line with the decline in schistosomiasis prevalence from 12.7% in 2007 to 2.2% in 2014 as observed with the gold standard KK test [15] performed in the epidemiological surveys in sentinel sites and in the national mapping [10]. Moreover, comparison of routine surveillance data with school-based mapping data per SD in 2014 showed that for most SD low prevalences based on KK were confirmed by low incidence rates by DS, and that in some districts where the prevalence with KK was zero, routine surveillance still detected some cases.

In contemporary Burundi, schistosomiasis transmission is low to moderate, the health care system is weak, and the (national) resources for health care limited. Furthermore, schistosomiasis diagnosis through KK and treatment of positive cases with PZQ is absent in the primary health care setting [18]. Despite these limitations, the current passive routine surveillance system of Burundi appears still be able to monitor the evolution of schistosomiasis in the ZI as well as in the ZNI. Both are equally important in the framework of disease elimination.

Our data hold promise for the use of routine diagnostic data collected at HC level as a cost-effective and sustainable strategy to monitor the impact of MDA campaigns and other schistosomiasis control interventions in Burundi. However, it should be borne in mind that DS, but also KK, have a reduced sensitivity especially in areas of low endemicity, such as Burundi [10]. Highly sensitive diagnostic tools to detect light-intensity infections are pivotal for monitoring progress from control towards elimination [19,20,21]. Several studies have now documented the lateral flow immunochromatographic point-of-care (POC) test detecting Schistosoma circulating cathodic antigen (CCA) in urine as a valuable alternative to the KK for the diagnosis of S. mansoni [22]. It is rapid, user-friendly, and considerably more sensitive than KK especially in areas of low prevalence [23]. While the POC-CCA assay has already shown its value as a mapping and monitoring in national control programmes [10, 22], its suitability for integration into the PHC system as a routine test for case management and surveillance/monitoring of intestinal schistosomiasis still needs to be investigated in more detail. Burundi is low endemic for intestinal schistosomiasis and currently aiming for elimination [10]. This, in combination with a relatively well-functioning NHIS system, would provide an ideal setting for such a study.

Conclusions

The results of this preliminary study suggest that routine surveillance at HC level may be able to monitor the impact of MDA with PZQ on intestinal schistosomiasis in Burundi. However, more sensitive routine diagnostic tests, such as the POC-CCA assay are desirable when moving from control to elimination of schistosomiasis. Integration of adequate diagnosis and treatment into the routine activities of primary health care facilities is essential for intestinal schistosomiasis to be controlled and eventually eliminated in Burundi.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The datasets generated and analysed during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CCA:

-

circulating cathodic antigen

- DH:

-

district hospital

- DNHIS:

-

Directorate of National Health Information System

- DS:

-

direct smear

- HC:

-

health centre

- HF:

-

health facility

- KK:

-

kato-katz

- MDA:

-

mass drug administration

- NHIS:

-

National Health Information System

- NTD:

-

neglected tropical diseases

- PHC:

-

primary health care

- POC-CCA:

-

point-of-care circulating cathodic antigen

- PZQ:

-

praziquantel

- SCI:

-

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative

- SD:

-

sanitary district

- SP:

-

sanitary province

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- ZI:

-

zone of intervention

- ZNI:

-

zone of non-intervention

References

Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368:1106–18.

Raso G, Vounatsou P, McManus DP, N’Goran EK, Utzinger J. A Bayesian approach to estimate the age-specific prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni and implications for schistosomiasis control. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:1491–500.

Steinmann P, Keiser J, Bos R, Tanner M, Utzinger J. Schistosomiasis and water resources development: systematic review, meta-analysis, and estimates of people at risk. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:411–25.

Clements AC, Brooker S, Nyandindi U, Fenwick A, Blair L. Bayesian spatial analysis of a national urinary schistosomiasis questionnaire to assist geographic targeting of schistosomiasis control in Tanzania, East Africa. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:401–15.

Chitsulo L, Engels D, Montresor A, Savioli L. The global status of schistosomiasis and its control. Acta Trop. 2000;77:41–51.

Tchouanguem HN, Fouelifack FY, Keugoung B, Fouelifa LD, Moyou RS. Current status of schistosomiasis in Santchou health area, (Santchou Health District, Cameroon western region). Pan Afr Med J. 2016;24:137.

de Bève F. Bilhariziose en Ruanda-Urundi et spécialement à Usumbura. Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1935;15:3–18.

Neujan G. Parasitisme intestinal chez les indigènes des Hauts Plateaux (environs de Kitega). Ann Soc Belg Med Trop. 1937;17:343–9.

Ndayishimiye O, Ortu G, Soares Magalhaes RJ, Clements A, Willems J, Whitton J, et al. Control of neglected tropical diseases in Burundi: partnerships, achievements, challenges, and lessons learned after four years of programme implementation. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e2684.

Ortu G, Ndayishimiye O, Clements M, Kayugi D, Campbell CH Jr, Lamine MS, et al. Countrywide reassessment of Schistosoma mansoni infection in Burundi using a urine-circulating cathodic antigen rapid test: informing the national control program. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:664–73.

Sousa-Figueiredo JC, Stanton MC, Katokele S, Arinaitwe M, Adriko M, Balfour L, et al. Mapping of schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminths in Namibia: the first large-scale protocol to formally include rapid diagnostic tests. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0003831.

Worrell CM, Bartoces M, Karanja DM, Ochola EA, Matete DO, Mwinzi PN, et al. Cost analysis of tests for the detection of Schistosoma mansoni infection in children in western Kenya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92:1233–9.

Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:392–404.

Verbeke G, Molenberghs G. Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. New York: Springer; 2000.

WHO. The control of schistosomiasis. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1993;830:1–86.

WHO. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: prevention and control. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2004;912:29–55.

WHO. Schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis: prevention and control. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2002;912:25–50.

Bizimana P, Polman K, Van Geertruyden JP, Nsabiyumva F, Ngenzebuhoro C, Muhimpundu E, et al. Capacity gaps in health facilities for case management of intestinal schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis in Burundi. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7:66.

Rollinson D, Knopp S, Levitz S, Stothard JR, Tchuem Tchuente LA, Garba A, et al. Time to set the agenda for schistosomiasis elimination. Acta Trop. 2013;128:423–40.

Adriko M, Standley CJ, Tinkitina B, Tukahebwa EM, Fenwick A, Fleming FM, et al. Evaluation of circulating cathodic antigen (CCA) urine-cassette assay as a survey tool for Schistosoma mansoni in different transmission settings within Bugiri District, Uganda. Acta Trop. 2014;136:50–7.

Lamberton PH, Kabatereine NB, Oguttu DW, Fenwick A, Webster JP. Sensitivity and specificity of multiple kato-katz thick smears and a circulating cathodic antigen test for Schistosoma mansoni diagnosis pre- and post-repeated-praziquantel treatment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8:e3139.

Sousa-Figueiredo JC, Betson M, Kabatereine NB, Stothard JR. The urine circulating cathodic antigen (CCA) dipstick: a valid substitute for microscopy for mapping and point-of-care diagnosis of intestinal schistosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2008.

Kittur N, Castleman JD, Campbell CH, King CH, Colley DG. Comparison of Schistosoma mansoni prevalence and intensity of infection, as determined by the circulating cathodic antigen urine assay or by the Kato-Katz fecal assay: a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;94:605–10.

Acknowledgements

Authors appreciated the Director of the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative, Professor Alan Fenwick, for supporting this project. They are also very thankful to the Ministry of Health of Burundi, the Schistosomiasis Consortium for Operational Research and Evaluation (SCORE) and the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI) for the data from the national mapping of 2014 used in this study. They also express their thanks to the staff of the DNIHS who helped to obtain these data.

Funding

The Schistosomiasis Control Initiative (SCI)/Imperial College and VLIR-UOS funded this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PB was involved in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the study and wrote the paper. KP made substantial contributions to the conception of the study, analysed and interpreted data and revised the manuscript critically. GO was involved in the conception of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and revision of the manuscript. MK was involved in the conception of the methodology, analysis and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript. JPVG made substantial contributions to the conception of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and critically revised the manuscript. FN, AN, UB and MN revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the National Ethics Committee of Burundi in September 2013. Authorisation from the Ministry of Public Health for the study was provided in May 2014.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bizimana, P., Polman, K., Ortu, G. et al. Can direct smear results that are routinely collected at health centre level be used for monitoring the impact of mass drug administration with praziquantel on schistosomiasis in Burundi? A preliminary assessment. Parasites Vectors 13, 206 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04076-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04076-4