Abstract

Background

Giardia duodenalis is an important intestinal protozoan infecting both humans and animals, causing significant public health concern and immeasurable economic losses to animal husbandry. Sheep and goats have been reported as common reservoirs of G. duodenalis, but only a limited amount of information is available for native breeds of these small ruminants in China. The present study investigated the prevalence and multilocus genotypes of G. duodenalis in black-boned sheep and goats, two important native breeds in Yunnan Province, southwestern China.

Methods

Fecal samples were collected from 336 black-boned goats and 325 black-boned sheep from five counties (Meishui, Shanshu, Shilin, Yongsheng and Nanping) of Yunnan Province and the genomic DNA was extracted from these feces. The prevalence of G. duodenalis was determined by the nested PCR targeting the β-giardin (bg) gene. The assemblages and multilocus genotypes (MLGs) were investigated based on analyses of three genetic loci, i.e. bg, glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) and triosephosphate isomerase (tpi).

Results

Giardia duodenalis infection was detected in both black-boned sheep and goats, and the prevalence of G. duodenalis in black-boned sheep (21.8%, 71/325) was significantly higher (χ2 = 36.63, df = 1, P < 0.001) than that in black-boned goats (4.8%, 16/336). Significant differences in prevalence were also observed in goats and sheep from different counties (χ2 = 39.83, df = 4, P < 0.001) and age groups (χ2 = 97.33, df = 3, P < 0.001). Zoonotic assemblage A and animal-specific assemblage E were identified in both black-boned sheep and goats with the latter as the predominant assemblage. Based on sequences obtained from the three genetic loci (bg, gdh and tpi), 16 MLGs were obtained in black-boned sheep and goats, including 15 MLGs in assemblage E and one MLG in assemblage A.

Conclusions

Our results not only extended the host range of G. duodenalis, but also revealed high genetic variations in G. duodenalis assemblages. The findings of the present study also provide baseline data for preventing and controlling G. duodenalis infection in black-boned sheep and goats in Yunnan Province.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Giardia duodenalis (syns Giardia lamblia, Giardia intestinalis) is one of the most common parasites that causes intestinal infections of humans and various animals worldwide [1,2,3], and about 280 million people have symptomatic infections annually [4, 5]. The prevalence of G. duodenalis in humans in developing countries is much higher than that in developed countries [6, 7]. In China, the average prevalence of G. duodenalis in humans was 0.85% from 2000 to 2017 (197/23,098) [3]; however, the infection rate is underestimated because people in many areas with poor medical care have not yet been assessed. Giardiasis, caused by G. duodenalis, is characterized by diarrhoea, abdominal pain, bloating, malabsorption and weight loss in symptomatic infections [1, 8, 9]. Moreover, diarrhoeal disease, causing about 800 000 fatalities worldwide per year, is the main cause of illness and death for children during the first five years of life [4, 10]; G. duodenalis is the second-most common pathogen detected in diarrhoeal stools of children between 12–24 months of age [7]. However, due to drug resistance and known cases of treatment failure [11, 12], it is essential to find the source of the infection for effective control of this parasitic disease.

Thus far, at least eight genetically distinct assemblages (A-H) of G. duodenalis have been identified using molecular biological analysis. Among them, assemblages A and B are believed to have zoonotic potential for their broad host range, and assemblage A is more frequently found in livestock than assemblage B, while the remaining assemblages (C-H) are animal-specific groups [1, 13, 14]. To better assess the zoonotic transmission of giardiasis and differentiate mixed infections of assemblages, high-resolution multilocus genotyping analysis using more intra-assemblage variation genes, including β-giardin (bg), glutamate dehydrogenase (gdh) and triosephosphate isomerase (tpi) genes, has been widely used to characterize G. duodenalis isolates from humans and animals [1, 15].

Sheep and goats are important for the animal husbandry economy and their populations are rising steadily in Asia. China has the largest population of sheep and goats around the world [16]. Thus far, a number of studies have reported the infection of G. duodenalis in sheep and goats in China, with prevalences of 1.82–13.11% [13, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23] and 0.95–27.78% [17, 20, 24,25,26,27,28,29,30], respectively. Although asymptomatic infection of G. duodenalis commonly occurs in sheep and goats [31], an outbreak of giardiasis in a sheep farm located in central Italy had G. duodenalis-infected lambs showing malabsorption, weight loss, decrease of feed conversion ratio, malodorous and poorly formed greenish feces [32], causing significant economic loss to sheep on this farm. Assemblages A, B and E have been identified in sheep and goats in China, with assemblage E as the most frequently detected assemblage [3, 13, 30]. The identification of zoonotic assemblages A and B suggests that sheep and goats with G. duodenalis infections are likely to be the source of human giardiasis.

Black-boned sheep and black-boned goats, two important native breeds originated from Nanping county, Yunnan Province, southwestern China [33], are believed to have a medicinal function and nutritional value, as well as a health care value due to the great quantity of melanin in their tissues [33, 34]. However, to date, there are no studies on G. duodenalis infection in black-boned sheep and goats. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to investigate the prevalence and assemblage distribution of G. duodenalis in black-boned sheep and goats, and to evaluate the zoonotic potential of G. duodenalis in these two native breeds using a high-resolution multilocus genotyping tool targeting three genes (bg, gdh and tpi) useful for studying intra-assemblage variation.

Methods

Sample collection

A total of 661 fecal samples were collected from five counties (Meishui, Shanshu, Shilin, Yongsheng and Nanping) in Yunnan Province, southwestern China in August 2017; of these, 325 fecal specimens were collected from black-boned sheep and 336 were collected from black-boned goats. Both male and female animals’ feces were collected, and these animals were divided into four age groups: 0–2 months; 3–6 months; 7–12 months; and > 12 months. Each fresh fecal specimen was randomly obtained from the rectum of each apparently healthy animal using a sterile disposal plastic glove. Approximately 5–20 g of feces were collected from each animal. The feces were marked with the sampling site, sex, age and breed immediately after collection, and kept on ice packs during transportation. All specimens were preserved in 2.5% potassium dichromate at 4 °C until genomic DNA extraction.

Genomic DNA extraction

To remove the potassium dichromate, approximately 300 mg of each fecal specimen was washed by centrifugation at 13,000 × g with sterilized distilled water until the supernatant was clear before genomic DNA extraction. Then, the genomic DNA of each washed fecal specimen was extracted using E.Z.N.A® Stool DNA kit (Omega Bio-tek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracts of genomic DNA were stored at -20 °C for further PCR analysis.

Nested PCR amplification

The prevalence of G. duodenalis in black-boned sheep and goats was determined by nested PCR targeting the bg gene using previously described primers and procedures [9, 35, 36]. Then, the bg-positive samples were analyzed by nested PCR at the gdh and tpi loci using previously described primers and procedures [9, 37]. Positive and negative controls were included in each PCR reaction. The secondary PCR products were screened by electrophoresis with 1% (w/v) agarose gels containing ethidium bromide.

Sequencing and sequence analysis

All G. duodenalis bg-, gdh- and tpi-positive secondary PCR products were sent to Xi’an Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. for direct sequencing. Sequences obtained were first proofread with their DNA peak-form graph using Chromas v.2.6. Then, the checked sequences were amended by aligning with reference sequences downloaded from GenBank database using the software Clustal X v.1.83 [38] to identify G. duodenalis assemblages. Samples simultaneously successfully amplified at all three genetic loci (bg, gdh and tpi) were used to form MLGs to further reveal the genetic diversity. The nomenclature of novel sequence subtypes identified in the present study and those undesignated subtype sequences previously deposited in GenBank followed that of the former studies [13, 23].

Statistical analysis

The differences in prevalence between different breeds, sexes, age groups and locations were calculated using a Chi-square test in SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The differences were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Prevalence of G. duodenalis in black-boned sheep and goats

In the present study, of the 661 animal fecal specimens examined, 87 were G. duodenalis bg-positive, giving a total prevalence of 13.2%. Among the positive samples, 71 were from black-boned sheep [prevalence of 21.8% (71/325)] (Table 1), and 16 were from black-boned goats [prevalence of 4.8% (16/336)] (Table 1); a significant difference was observed between these two species (χ2 = 36.63, df = 1, P < 0.001). We also found that the occurrence of G. duodenalis decreased as age increased in these animals, with the highest prevalence found in animals < 2 months (54.3%, 19/35), followed by 3–6 months (37.3%, 19/51), 7–12 months (16.3%, 41/252) and > 12 months (2.5%, 8/323) (χ2 = 97.33, df = 3, P < 0.001).

Significant differences in prevalence of G. duodenalis were found among different age groups of both black-boned sheep (χ2 = 46.11, df = 3, P < 0.001) and goats (χ2 = 32.51, df = 3, P < 0.001). Of the 325 fecal samples collected from the four age groups of black-boned sheep, the highest prevalence of G. duodenalis was found for the 0–2-month group (59.4%, 19/32); however, G. duodenalis was not found in this age group of black-boned goats (0/3) due to the number of samples being too small. The highest prevalence of G. duodenalis was found in 3–6 month black-boned goats (24.1%, 7/29). In black-boned sheep, the lowest prevalence was found in sheep aged more than 12 months (5.7%, 7/123), while only one of 200 (0.5%) black-boned goats in this age group was found with G. duodenalis infection (Table 2).

Distribution of G. duodenalis assemblages

Sequence analysis of the bg gene indicated two assemblages (A and E) of G. duodenalis in both black-boned sheep and goats. Of the 71 bg-positive black-boned sheep samples, 70 isolates from three counties and four age groups belonged to the animal-specific assemblage E, while only one isolate from a 3-month sheep in Shilin county was identified as the zoonotic assemblage A. Ten isolates of assemblage E were detected in 16 bg-positive black-boned goat samples and all 6 assemblage A isolates were detected in Meishui County (Tables 1 and 2).

Subtypes of assemblages A and E

Among the 325 samples of black-boned sheep examined, a total of 35 and 43 sequences were obtained by amplifying 71 bg-positive black-boned sheep samples at the gdh and tpi loci, respectively (Table 1). At the bg locus, 14 subtypes were generated by comparison of the 71 amended sequences obtained from black-boned sheep, with one and 13 identified to be assemblages A and E, respectively, including nine known subtypes (A5, E2, E3, E5, E6, E8, E9, E13 and E15) and five novel subtypes (named as E16, E17, E18, E20 and E22) (Table 3). Four subtypes were yielded by analysis of 35 amended sequences at the gdh locus. All of them represented assemblage E and three of them had been previously published with no subtype names; here we named them as E31, E32 and E33, respectively, while only one was identified as a novel subtype (named as E34) (Table 4). Sequence analysis of the 43 tpi-positive samples revealed one subtype of assemblage A and four subtypes of assemblage E in black-boned sheep. Among them, three subtypes had been previously reported, named as A4, E3 and E5 (Table 5). One sequence had been previously published without a subtype name; here we named it as E29, while the remaining novel subtype was named as E30 (Table 5).

In black-boned goats, one subtype of assemblage A and six subtypes of assemblage E were identified at the bg locus, including four known subtypes (named as A5, E2, E5 and E13) and three novel subtypes (named as E16, E19 and E21) (Table 3). At the gdh locus, one known subtype (designated as A1), two previously published sequence with no subtype name (named as E32 and E33) were identified (Table 4). At the tpi locus two known assemblage A subtypes (A1 and A4), one known assemblage E subtype (E3) and one previously published sequence with no subtype name (named as E28) were identified (Table 5).

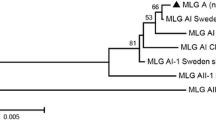

Multilocus genotypes

In total, 33 samples were simultaneously amplified at all three intra-assemblage variation genetic loci, including 26 samples from black-boned sheep and seven from black-boned goats. Of the 26 black-boned sheep samples, sequences obtained from 24 samples belonged to assemblage E, forming 14 novel assemblage E MLGs (named as MLG-E1 to MLG-E8 and MLG-E10 to MLG-E15), and two samples were mixed infection with assemblages E and A (Table 6). In black-boned goats, three distinct assemblage E MLGs (named as MLG-E1, MLG-E2 and MLG-E9) were yielded from three samples and one assemblage A MLG (named as MLG-A1) was identified from another three samples; the remaining sample was a mixed infection with assemblages E and A (Table 6).

In black-boned sheep, MLG-E1 was found in four samples from two counties. MLG-E4, MLG-E6 and MLG-E7 were each found in two samples from one county. MLG-E5 and MLG-E10 were each found in three samples from one county. The remaining eight assemblage E MLGs were observed in only one sample (Table 7). Most MLGs were found in Shilin county, three MLGs were seen in Yongsheng county and only one MLG was observed in Nanping county (Table 7). Most MLGs were observed in black-boned sheep of 7–12 months (7/15) and 0–2 months (6/15) (Table 8).

In black-boned goats, both assemblage E MLGs and assemblage A MLGs were found. MLG-E1 and MLG-E2 were detected in 9-month-old and 2-year-old black-boned goats from Nanping county, respectively. MLG-E9 was found in a 3-month-old black-boned goat from Meishui county. All three samples of MLG-A1 were from Meishui county, two of them were collected from black-boned goats of 3–6 months and one was from a black-boned goat of the 7–12 months group (Tables 7 and 8).

Discussion

Giardiasis, an important parasitic disease, is believed to be associated with water because infected hosts could shed Giardia cysts into environment which could cause water contamination [39]. Infection of people and animals through ingestion of water contaminated with infective cysts could lead to great public concern and enormous economic loss to animal husbandry [16]. One experimental study indicated that lambs infected with G. duodenalis showed a lower rate of weight gain, longer time to reach slaughter weight and lower carcass weight than control lambs [40].

In this investigation, G. duodenalis was detected in both black-boned sheep and goats, with respective prevalences of 21.8% (71/325) and 4.8% (16/336). The prevalence in black-boned sheep was higher than in other kinds of sheep previously reported in China (1.82–13.11%) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], several parts of Australia (20.2%, 11.1%), Spain (11.1%, 19.2%), Ghana (12.9%), Italy (1.5%), Iran (19.8%) and Ethiopia (2.6%) [31, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47], but lower than that in Switzerland (29.8%), Canada (38%), USA (25.4%), Belgium (35.8%), Norway (26.8%), some areas of Australia (63.7%), Spain (42%, 89.2%), Greece (37.3%) and Brazil (34%) [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. As black-boned sheep age, the G. duodenalis prevalence tends to decrease, with a significant difference being observed among different age groups. Our results were consistent with previous reports [17, 22, 23, 41, 49, 56, 57], suggesting that lambs could be more susceptible to G. duodenalis than adult sheep.

Similarly, the G. duodenalis prevalence in black-boned goats was slightly higher than that reported in some provinces of China [17, 20, 25,26,27] and Uganda (0) [58]. However, it was lower than most previous reports in goats worldwide [24, 26, 28,29,30,31, 42, 46, 48, 51, 55, 59,60,61,62,63]. There was a significant difference in the prevalence of G. duodenalis among different age groups, and the prevalence in black-boned goat kids (< 6 months) (21.9%, 7/32) was significantly higher than in black-boned goats over 6 months (3.0%, 9/304). A higher G. duodenalis prevalence in goat kids has also been observed in other studies [17, 29, 30, 48, 51, 55, 59, 64]. Many factors could contribute to these variations, e.g. the age of tested animals, sensitivity of diagnostic methods, loci amplified, sample sizes, climates and breeding methods. For example, the prevalence in 0–2-month black-boned sheep was 59.4% (19/32), while no G. duodenalis was detected in black-boned goats of this age group due to the limited number of sampled animals (n = 3).

Assemblage E was the most prevalent genotype in both black-boned sheep (70/71) and goats (10/16) in our study. Assemblage E was also reported as the predominate genotype in sheep and goats in other studies [13, 17, 23, 24, 29,30,31, 43, 45, 46, 50,51,52,53,54, 56, 57, 59, 61, 62]. Although assemblage E was generally believed to be animal-specific [65], sporadic reports from some areas with poor conditions in Egypt, Australia and Brazil suggest that it can also be found in humans [66,67,68,69,70], indicating its zoonotic transmission. In some studies, both zoonotic assemblages A and B were observed in sheep and goats [17, 30, 44, 52, 61,62,63]. However, in our study, only one black-boned sheep and six black-boned goats were infected with G. duodenalis assemblage A. Interestingly, genomic analysis of assemblages A, B and E showed that the nucleotide similarity between assemblages A and E is much higher than that between assemblages A and B [71, 72]. These results suggest that infected black-boned sheep and goats have the opportunity to transmit G. duodenalis to humans.

To further reveal the genetic variations in assemblages A and E, another two genetic loci (gdh and tpi) of 87 bg-positive samples were analyzed by the multilocus genotyping tool with high resolution [9]. A total of four assemblage E subtypes at the gdh locus, four assemblage E subtypes and one assemblage A subtype at the tpi locus were identified in black-boned sheep. Two assemblage E subtypes and one assemblage A subtype at the gdh locus, and two assemblage E subtypes and two assemblage A subtypes at the tpi locus were observed in black-boned goats (Tables 4 and 5). In addition, three samples had different assemblages at the three loci (Table 6). Fifteen MLGs of assemblage E and one MLG of assemblage A were yielded in 30 samples amplified successfully at all three loci with the same assemblage genotype. These findings suggest that there is a high subtype diversity and genetic variation in assemblages A and E. In addition, a higher prevalence of G. duodenalis assemblage A in black-boned goats (62.5%, 10/16) and the presence of the assemblage A MLGs suggest that the black-boned goats has higher potential in transmitting zoonotic G. duodenalis than the black-boned sheep.

Conclusions

The present study revealed the presence and identified assemblages of G. duodenalis in black-boned sheep and goats in Yunnan Province, southwestern China. Assemblages A and E were found in both black-boned sheep and goats, with assemblage E being the most prevalent in these two native species. The presence of zoonotic assemblage A in black-boned sheep and goats suggests their zoonotic potential. Multilocus genotyping at bg, tpi and gdh loci formed 14 novel assemblage E MLGs in black-boned sheep and four novel MLGs (three assemblage E MLGs and one assemblage A MLG) in black-boned goats. These results provide baseline data for preventing and controlling G. duodenalis infection in black-boned sheep and goats as well as humans.

Abbreviations

- Bg :

-

β-giardin

- Gdh :

-

glutamate dehydrogenase

- MLGs:

-

multilocus genotypes

- Tpi :

-

triosephosphate isomerase

References

Feng Y, Xiao L. Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:110–40.

Ryan U, Cacciò SM. Zoonotic potential of Giardia. Int J Parasitol. 2013;43:943–56.

Li J, Wang H, Wang R, Zhang L. Giardia duodenalis infections in humans and other animals in China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2004.

Einarsson E, Ma’ayeh S, Svärd SG. An up-date on Giardia and giardiasis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;34:47–52.

Squire SA, Ryan U. Cryptosporidium and Giardia in Africa: current and future challenges. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:195.

Halliez MC, Buret AG. Extra-intestinal and long term consequences of Giardia duodenalis infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8974–85.

Fink MY, Singer SM. The intersection of immune responses, microbiota, and pathogenesis in giardiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:901–13.

Soares R, Tasca T. Giardiasis: an update review on sensitivity and specificity of methods for laboratorial diagnosis. J Microbiol Methods. 2016;129:98–102.

Wang SS, Yuan YJ, Yin YL, Hu RS, Song JK, Zhao GH. Prevalence and multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in pigs of Shaanxi Province, northwestern China. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:490.

Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Farag TH, Panchalingam S, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–22.

Ansell BR, McConville MJ, Ma’ayeh SY, Dagley MJ, Gasser RB, Svärd SG, et al. Drug resistance in Giardia duodenalis. Biotechnol Adv. 2015;33:888–901.

Leitsch D. Drug resistance in the microaerophilic parasite Giardia lamblia. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2015;2:128–35.

Jin Y, Fei J, Cai J, Wang X, Li N, Guo Y, et al. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in Tibetan sheep and yaks in Qinghai, China. Vet Parasitol. 2017;247:70–6.

Cacciò SM, Lalle M, Svärd SG. Host specificity in the Giardia duodenalis species complex. Infect Genet Evol. 2018;66:335–45.

Lebbad M, Mattsson JG, Christensson B, Ljungström B, Backhans A, Andersson JO, et al. From mouse to moose: multilocus genotyping of Giardia isolates from various animal species. Vet Parasitol. 2010;168:231–9.

Robertson LJ. Giardia and Cryptosporidium infections in sheep and goats: a review of the potential for transmission to humans via environmental contamination. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:913–21.

Zhang W, Zhang X, Wang R, Liu A, Shen Y, Ling H, et al. Genetic characterizations of Giardia duodenalis in sheep and goats in Heilongjiang Province, China and possibility of zoonotic transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1826.

Zhu D, Wei J, Qi M, Li M, Shi Y, Du H, et al. Investigation on the intestinal parasites infection in large tailed Han sheep in Jiaxian, Henan. China Herb Sci. 2012;32:69–71 (In Chinese).

Li M, Peng Y, Zhu D, Jian F, Wang G, Ma H, et al. Survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasites in sheep. Chin Anim Husb Vet Med. 2013;40:201–5 (In Chinese).

Ma L, Sotiriadou I, Cai Q, Karanis G, Wang G, Wang G, et al. Detection of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in agricultural and water environments in the Qinghai area of China by IFT and PCR. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:3177–84.

Sui P, Li J, Qi M, Yu F, Luo N, Ning C. Investigation on intestinal parasitic infections in sheep and goat in Anyang, China. Anim Husb Vet Med. 2015;47:123–6 (In Chinese).

Ye J, Xiao L, Wang Y, Guo Y, Roellig DM, Feng Y. Dominance of Giardia duodenalis assemblage A and Enterocytozoon bieneusi genotype BEB6 in sheep in Inner Mongolia, China. Vet Parasitol. 2015;210:235–9.

Wang H, Qi M, Zhang K, Li J, Huang J, Ning C, Zhang L. Prevalence and genotyping of Giardia duodenalis isolated from sheep in Henan Province, central China. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;39:330–5.

Gu YF, Wang LK, Li Y, Li L, Chu XH, Xin DW, et al. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Giardia lamblia isolates from goats in Anhui Province. Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2014;32:401–3 (In Chinese).

Li M, Zhu D, Qi M, Song D, Shi Y, Zhao Z, et al. Survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasites in Yaoshan white goat. Chin Anim Husb Vet Med. 2012;39:191–4 (In Chinese).

Zhu D, Lv Y, Li M, Zhang Z, Jian F, Song D, et al. Survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasites in goats in partial regions of China. Chin Herb Sci. 2013;33:43–6 (In Chinese).

Cao S, Zhang Z, Cui Y, Wang J, Lv Y, Li D, et al. Survey on the prevalence of intestinal parasites in dairy goats in partial regions of China. J Henan Agri Sci. 2015;44:146–9 (In Chinese).

Chen J, He W, Ren H, Gao L, Ning C. A survey of prevalence of intestinal parasites in goats in part of the breeding farms of Chongqing. J Southwest Univ. 2015;37:71–5 (In Chinese).

Peng XQ, Tian GR, Ren GJ, Yu ZQ, Lok JB, Zhang LX, et al. Infection rate of Giardia duodenalis, Cryptosporidium spp and Enterocytozoon bieneusi in cashmere, dairy and meat goats in China. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;41:26–31.

Yin YL, Zhang HJ, Yuan YJ, Tang H, Chen D, Jing S, et al. Prevalence and multi-locus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis from goats in Shaanxi Province, northwestern China. Acta Trop. 2018;182:202–6.

Jafari H, Jalali MH, Shapouri MS, Hajikolaii MR. Determination of Giardia duodenalis genotypes in sheep and goat from Iran. J Parasit Dis. 2014;38:81–4.

Aloisio F, Filippini G, Antenucci P, Lepri E, Pezzotti G, Caccio SM, et al. Severe weight loss in lambs infected with Giardia duodenalis assemblage B. Vet Parasitol. 2006;142:154–8.

Deng WD, Xi DM, Guo X, Yang SL, Shi XW, Mao HM. Pigmentation in black-boned sheep (Ovis aries): association with polymorphism of the tyrosinase gene. Mol Biol Rep. 2008;35:379–85.

Tu YG, Xie MY, Sun YZ, Tian YG. Structural characterization of melanin from Black-bone silky fowl (Gallus gallus domesticus Brisson). Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:134–6.

Cacciò SM, De Giacomo M, Pozio E. Sequence analysis of the β-giardin gene and development of a polymerase chain reaction–restriction fragment length polymorphism assay to genotype Giardia duodenalis cysts from human faecal samples. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:1023–30.

Lalle M, Pozio E, Capelli G, Bruschi F, Crotti D, Caccio SM. Genetic heterogeneity at the beta-giardin locus among human and animal isolates of Giardia duodenalis and identification of potentially zoonotic subgenotypes. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:207–13.

Sulaiman IM, Fayer R, Bern C, Gilman RH, Trout JM, Schantz PM, et al. Triosephosphate isomerase gene characterization and potential zoonotic transmission of Giardia duodenalis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1444–52.

Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–82.

Lv S, Tian LG, Liu Q, Qian MB, Fu Q, Steinmann P, et al. Water-related parasitic diseases in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:1977–2016.

Olson ME, McAllister TA, Deselliers L, Morck DW, Cheng KJ, Buret AG, et al. Effects of giardiasis on production in a domestic ruminant (lamb) model. Am J Vet Res. 1995;56:1470–4.

Giangaspero A, Paoletti B, Iorio R, Traversa D. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis from sheep in central Italy. Parasitol Res. 2005;96:32–7.

Castro-Hermida JA, Almeida A, González-Warleta M, Correia da Costa JM, Rumbo-Lorenzo C, Mezo M. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia duodenalis in healthy adult domestic ruminants. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1443–8.

Yang R, Jacobson C, Gordon C, Ryan U. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia species in pre-weaned sheep in Australia. Vet Parasitol. 2009;161:19–24.

Castro-Hermida JA, García-Presedo I, Almeida A, González-Warleta M, Correia Da Costa JM, Mezo M. Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis in two areas of Galicia (NW Spain). Sci Total Environ. 2011;409:2451–9.

Yang R, Jacobson C, Gardner G, Carmichael L, Campbell AJ, Ryan U. Development of a quantitative PCR (qPCR) for Giardia and analysis of the prevalence, cyst shedding and genotypes of Giardia present in sheep across four states in Australia. Exp Parasitol. 2014;137:46–52.

Squire SA, Yang R, Robertson I, Robertson I, Ayi I, Ryan U. Molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in farmers and their ruminant livestock from the Coastal Savannah zone of Ghana. Infect Genet Evol. 2017;55:236–43.

Wegayehu T, Karim MR, Li J, Adamu H, Erko B, Zhang L, et al. Prevalence and genetic characterization of Cryptosporidium species and Giardia duodenalis in lambs in Oromia Special Zone, Central Ethiopia. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13:22.

Taminelli V, Eckert J. The frequency and geographic distribution of Giardia infections in ruminants in Switzerland. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 1989;131:251–8 (In German).

Olson ME, Thorlakson CL, Deselliers L, Morck DW, McAllister TA. Giardia and Cryptosporidium in Canadian farm animals. Vet Parasitol. 1997;68:375–81.

Santín M, Trout JM, Fayer R. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia species and genotypes in sheep in Maryland. Vet Parasitol. 2007;146:17–24.

Geurden T, Thomas P, Casaert S, Vercruysse J, Claerebout E. Prevalence and molecular characterisation of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in lambs and goat kids in Belgium. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:142–5.

Robertson LJ, Gjerde BK, Furuseth Hansen E. The zoonotic potential of Giardia and Cryptosporidium in Norwegian sheep: a longitudinal investigation of 6 flocks of lambs. Vet Parasitol. 2010;171:140–5.

Sweeny JP, Ryan UM, Robertson ID, Yang R, Bell K, Jacobson C. Longitudinal investigation of protozoan parasites in meat lamb farms in southern Western Australia. Prev Vet Med. 2001;101:192–203.

Gómez-Muñoz MT, Cámara-Badenes C, Martínez-Herrero Mdel C, Dea-Ayuela MA, Pérez-Gracia MT, Fernández-Barredo S, et al. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in lambs from Spain reveals a high heterogeneity. Res Vet Sci. 2012;93:836–42.

Tzanidakis N, Sotiraki S, Claerebout E, Ehsan A, Voutzourakis N, Kostopoulou D, et al. Occurrence and molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp. in sheep and goats reared under dairy husbandry systems in Greece. Parasite. 2014;21:45.

Paz e Silvia FM, Lopes RS, Bresciani KD, Amarante AF, Araujo JP Jr. High occurrence of Cryptosporidium ubiquitum and Giardia duodenalis genotype E in sheep from Brazil. Acta Parasitol. 2014;59:193–6.

Ryan UM, Bath C, Robertson I, Read C, Elliot A, McInnes L, et al. Sheep may not be an important zoonotic reservoir for Cryptosporidium and Giardia parasites. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4992–7.

Nolan MJ, Unger M, Yeap YT, Rogers E, Millet I, Harman K, et al. Molecular characterisation of protist parasites in human-habituated mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei), humans and livestock, from Bwindi impenetrable National Park, Uganda. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:340.

Ruiz A, Foronda P, González JF, Guedes A, Abreu-Acosta N, Molina JM, et al. Occurrence and genotype characterization of Giardia duodenalis in goat kids from the Canary Islands, Spain. Vet Parasitol. 2008;154:137–41.

Berrilli F, D’Alfonso R, Giangaspero A, Marangi M, Brandonisio O, Kaboré Y, et al. Giardia duodenalis genotypes and Cryptosporidium species in humans and domestic animals in Côte d’Ivoire: occurrence and evidence for environmental contamination. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2012;106:191–5.

Lim YA, Mahdy MA, Tan TK, Goh XT, Jex AR, Nolan MJ, Sharma RS, Gasser RB. First molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis from goats in Malaysia. Mol Cell Probes. 2013;27:28–31.

Di Cristanziano V, Santoro M, Parisi F, Albonico M, Shaali MA, Di Cave D, et al. Genetic characterization of Giardia duodenalis by sequence analysis in humans and animals in Pemba Island, Tanzania. Parasitol Int. 2014;63:438–41.

Utaaker KS, Myhr N, Bajwa RS, Joshi H, Kumar A, Robertson LJ. Goats in the city: prevalence of Giardia duodenalis and Cryptosporidium spp in extensively reared goats in northern India. Acta Vet Scand. 2017;59:86.

Bomfim TC, Huber F, Gomes RS, Alves LL. Natural infection by Giardia sp. and Cryptosporidium sp. in dairy goats: associated with possible risk factors of the studied properties. Vet Parasitol. 2005;134:9–13.

Adam RD. Biology of Giardia lamblia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:447–75.

Foronda P, Bargues MD, Abreu-Acosta N, Periago MV, Valero MA, Valladares B, et al. Identification of genotypes of Giardia intestinalis of human isolates in Egypt. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:1177–81.

Helmy YA, Klotz C, Wilking H, Krücken J, Nöckler K, Von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, et al. Epidemiology of Giardia duodenalis infection in ruminant livestock and children in the Ismailia Province of Egypt: insights by genetic characterization. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:321.

Abdel-Moein KA, Saeed H. The zoonotic potential of Giardia intestinalis assemblage E in rural settings. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:3197–202.

Fantinatti M, Bello AR, Fernandes O, Da-Cruz AM. Identification of Giardia lamblia Assemblage E in humans points to a new anthropozoonotic cycle. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1256–9.

Zahedi A, Field D, Ryan U. Molecular typing of Giardia duodenalis in humans in Queensland - first report of assemblage E. Parasitology. 2017;44:1154–61.

Franzen O, Jerlström-Hultqvist J, Castro E, Sherwood E, Ankarklev J, Reiner DS, et al. Draft genome sequencing of Giardia intestinalis assemblage B isolate GS: is human giardiasis caused by two different species? PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000560.

Jerlström-Hultqvist J, Franzen O, Ankarklev J, Xu F, Nohynkova E, Andersson JO, et al. Genome analysis and comparative genomics of a Giardia intestinalis assemblage E isolate. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:543.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Xuemei Wu and Haoxian Wu for technical assistance.

Funding

Project support was provided by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP) (grant no. CAAS-ASTIP-2016-LVRI-03), the Elite Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and the Excellent Scientist Fund of Yunnan Agricultural University (grant no. 2015JY03).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the findings of this article are included within the article. Representative nucleotide sequences generated in this research were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers MK327158-MK327185.

Authors’ contributions

XQZ and GHZ conceived and designed the study, and critically revised the manuscript. DC performed the experiment, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. ZL, LQS, FCZ and JFY collected the fecal samples. YZ, SSW and SCX helped in the implementation of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of the present study has been reviewed and approved by the Animal Administration and Ethics Committee of Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. All fecal samples were collected from the black-boned sheep and goats after the permission of the farm owners or managers, and all procedures is performed strictly in accordance with the requirements of Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of the People’s Republic of China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, D., Zou, Y., Li, Z. et al. Occurrence and multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in black-boned sheep and goats in southwestern China. Parasites Vectors 12, 102 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3367-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3367-1