Abstract

Background

The red fox Vulpes vulpes is the most common mesocarnivore in Europe and with a wide geographical distribution and a high density in most terrestrial habitats of the continent. It is fast urbanising species, which can harbor high numbers of different tick species, depending on the region. Here we present the results of a large-scale study, trying to disentangle the intricate relationship between environmental factors and the species composition of ectoparasites in red foxes. The samples were collected in Transylvania (Romania), a region with a diverse geography and high biodiversity. The dead foxes (collected primarily through the National Surveillance Rabies Program) were examined carefully for the presence of ticks.

Results

Ticks (n = 4578) were found on 158 foxes (out of 293 examined; 53.9%). Four species were identified: Dermacentor marginatus, Ixodes canisuga, I. hexagonus and I. ricinus. The most common tick species was I. hexagonus (mean prevalence 37.5%, mean intensity 32.2), followed by I. ricinus (15.0%; 4.86), I. canisuga (4.8%; 7.71) and D. marginatus (3.7%; 3.45). Co-occurrence of two or more tick species on the same host was relatively common (12.6%), the most common co-occurrence being I. hexagonus - I. ricinus. For D. marginatus and I. canisuga the highest prevalence was recorded in lowlands, for I. hexagonus in hilly areas, while for I. ricinus in mountains.

Conclusions

Altitude influenced the intensity of parasitism, with highest intensity observed for all Ixodes species in hilly areas. Dermacentor marginatus occurred only in lowlands, I. canisuga in lowlands and hilly areas while the other two species occurred in all of the regions studied. Foxes from lower altitudes had the most tick species associated, with most incidences of co-parasitism also recorded here. Land use affected tick-species composition, with the presence of D. marginatus strongly associated with the extension of arable areas and lack of forests. The presence of I. hexagonus was determined only by the extent of arable lands. As foxes are frontrunners of wildlife urbanization process, with a continuous increase of their numbers in urban areas, the knowledge of their ticks’ ecology (and the pathogens vectored by these) is of utmost importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ticks are probably responsible for transmitting the highest number of pathogens, being competent vectors for a large number of piroplasms, viruses or bacteria. They are the medically most important group of arthropods in Europe, with an estimated 85,000 cases reported only for Lyme borreliosis [1], having also high associated health-care costs for most tick-borne diseases. In addition, ticks transmit a wide range of pathogens affecting livestock and companion animals [2, 3].

The medical importance of tick-borne diseases is acknowledged and most vectored diseases have a long epidemiological history; still, several tick-borne diseases show an emerging pattern all over Europe (and some even globally). Tick and host distributions are generally known in Europe [1] and the most important hosts of the different tick species have been identified for long time [4]; however, the delicate relationship that governs this co-occurrence still requires further studies.

The red fox (Vulpes vulpes) is the most common mesocarnivore in Europe, with a wide geographical distribution and a high density in most terrestrial habitats of the continent [5–8]. Being a species which successfully adapted to most habitats (even the most highly altered ones, like cities), it is a prime candidate for harboring and distributing en-mass different parasite species [9–11] in areas where high density human population and/or domesticated livestock occur [12–15]. It is a sedentary and territorial species, with a relatively small home range [12, 16]. Thus, as host for ticks (and pathogens transmitted by ticks) the red fox has an utmost importance, not only from biological, but also from epidemiological perspective [13, 17]. Moreover, foxes can harbor high numbers of different tick species and the faunal composition of these tick loads may differ from site to site [18–20]. While ticks may not pose significant health risk directly related to hematophagy, their importance resides in their capacity of transmitting pathogens. Tick communities harbored by foxes were extensively studied in western [19–24] and central Europe [17, 18, 25–27]. However, studies are scant in the eastern part of the continent. There is no large-scale study published for Romania on ticks of foxes, with the only paper on the subject being a list of records [28]. The red fox is the most common wild carnivore in the country, occurring in all terrestrial habitats [29]. Here we present the results of a study targeting the fox-tick relationship in the landscape of the north-western and central part of Romania (Transylvania), an area which presents a high diversity of landscape features (mostly covered by the Carpathians, but incorporating parts of the Pannonian Plain, with altitudes ranging from 90 to 2000 m above sea level, a.s.l.), providing an excellent background to study the influence the environment may have on the composition and tick-burdens in red foxes. Our study is the first of this kind which tries to disentangle the intricate relationship between environmental factors and the species’ composition of ectoparasites in a common mesocarnivore. Also we highlight the importance of the altitude and land use for this host and the parasite species harboured in the context of vector-borne disease potential they may pose.

Methods

Study region

The samples were collected in the historical region of Transylvania, in Romania (Fig. 1). The region has a diverse geography (and implicitly climate), dominated by the Carpathian Mountains (Transylvanian Alps). It is one of the wildest areas in Europe, with a high degree of natural and semi-natural vegetation and an exceptional biodiversity [30]. The area has high forest cover (42%), with most regions still maintaining traditional low intensity or subsistence agriculture, favoring a mosaic-like landscape composition [31, 32]. The sample collection sites are distributed in most important land use types, and cover all altitude ranges (91–1789 m a.s.l.) where red foxes may occur in the region. The samples were collected from red foxes, received as corpses from the National Surveillance of Rabies Program managed by the Romanian Agency for Veterinary and Public Health, based on sub-samples of animals resulted from commercial hunting and pest-control activities. All the animals received were collected using guns by licensed hunters (professional and amateur alike) in the course of organized game-management activities. Corpses of animals free of rabies were transported to our laboratory according to the current laws on animal corpse transport and zoonotic risks. A smaller percent of the controlled animals was received as road-kills (n = 12; 4.1%) (the University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine holds a national-wide license and is fully equipped for collection and disposal of biohazardous and medical waste, including animal carcasses). No live fox was harmed for the sake of this study.

The tick data

The foxes were stored in individual plastic bags deep frozen until examination. The collection period lasted 24 months, between May 2010 and April 2012. The whole body surface of each fox was examined carefully for the presence of ticks. The parasites were stored in 87% ethanol in separate vials from each host. While special care was taken to collect all ticks, we are not fully confident that all individuals of larval stages were found in each animal. Ticks were identified to species and development stage using morphological keys [33, 34].

Land use

The location of each collection site was geo-referenced and we collected environmental predictors using a grid 2 × 2 km cells containing the geo-referenced coordinates of the collection site. These cells had 400 ha, similar to the average red fox home range from semi-natural and natural habitats from all over Europe (mean 413.42 ha; range 12.95–1990.00 ha; standard deviation, SD, 393.1192 ha, n = 84 studies, [5, 6, 8, 35]). These cells were the unit for parasitological (mean intensity, frequency, prevalence of ticks on foxes) and land use data. To assess land use, we used CORINE LandCover (European Environment Agency, http://www.eea.europa.eu/). We used five predictors (altitude, per cent of arable land/grassland/urbanized areas/forest cover; see Table 1 for the associated CORINE LandCover categories). There was no statistical difference (χ 2 = 0.2258, df = 3, P < 0.97) between land use composition inside the sampled 2 × 2 km plots and the overall land use composition of the region, thus we consider that our results may be generalized for the whole region.

Statistical procedures

Mean intensity, frequency, prevalence and its 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using the software Quantitative Parasitology 3.0 [36]. Sample prevalence data were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Relationship between tick prevalence and environmental predictors (land use and altitude) was tested using Spearman’s rank correlation. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

Results

Tick parasitism

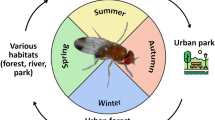

Altogether 293 foxes collected from 10 counties and at least 186 different locations were examined for ticks (Fig. 1). For a number of 48 foxes (16.4%), the exact collection site was unknown, thus these were excluded from the geographical analysis. Foxes were collected in each month; however, their distribution was not even, with most foxes hunted in autumn and winter months (due to hunting regulations, Fig. 2). Ticks (n = 4578) were found on 158 foxes (53.9%), with four tick species identified: Dermacentor marginatus, Ixodes canisuga, I. hexagonus and I. ricinus (Table 2). The most common tick species was I. hexagonus (mean prevalence 37.5%, CI: 31.4–43.5; mean intensity 32.2), followed by I. ricinus (mean prevalence 15.0%, CI: 10.1–19.8; mean intensity 4.86), I. canisuga (mean prevalence 4.8%, CI: 2.1–7.5; mean intensity 7.71), and D. marginatus (mean prevalence 3.7%, CI: 1.3–6.1, mean intensity 3.45). Most foxes (n = 104, 65.8%) had a low intensity of parasitism, with less than 5 ticks, while 7 foxes hosted more than 100 ticks, with one individual holding 2229 ticks, all larvae (Fig. 3). Co-occurrence of two or more tick species on the same host was relatively common, with 12.6% of foxes with ticks harboring more than one species (Table 3). The most common co-occurrence of different tick species on single foxes was I. hexagonus - I. ricinus (40% of all co-parasitism cases).

Importance of altitude and land use

Highest prevalence of tick occurrence was noted in foxes collected on lowlands (altitude below 200 m), followed by foxes in hilly areas (200–700 m) (mostly I. hexagonus). Lowest number of ticks was found in foxes of mountainous regions (above an altitude of 700 m). For two species (D. marginatus and I. canisuga) the highest prevalence was recorded in lowlands, for I. hexagonus in hilly areas, while for I. ricinus in mountain areas. However, none of these differences were significant.

Altitude also influenced the intensity of parasitism, with highest intensity observed for all but one tick species (D. marginatus, found only in lowlands) in hilly areas (Table 4). The geographical distribution of different tick species was also determined by altitude, with D. marginatus occurring only in lowlands (mean altitude 128.9 m, CI: 116–130, n = 11); I. canisuga in lowlands and hilly areas (mean altitude 266.2 m, CI: 112.2–492.7, n = 14; Fig. 4). The other two species occurred in all the regions studied, but with a different mean altitude of occurrence (mean altitude for I. hexagonus 322.2 m, CI: 156.2–380.5, n = 84; for I. ricinus 404.3 m, CI: 148.7–522.5, n = 42; Fig. 4). For all but one species (I. hexagonus) altitude was the most important factor determining presence (Table 5). Foxes from lower altitudes had the most tick species associated; with most incidences of co-parasitism noted below the elevation of 300 m (mean altitude for co-parasitism incidences 261.5 m, CI: 118.2–387.7, n = 18).

Land use also influenced tick-species composition, with occurrence of D. marginatus highly associated to the extension of arable areas and lack of forests inside the 2 × 2 km cell, while the presence of I. hexagonus was determined only by the extent of arable lands. Presence of forests was correlated with the lack of D. marginatus and I. canisuga (Table 5). We found no influence of the extent of urban areas inside the sample cell on neither of the identified tick species. No effect of seasonality on the geographical distribution was observed.

Discussion

In this study ticks collected from 293 red foxes from 183 individual locations were analyzed. We found that foxes had diverse tick assemblages according to season, land use and altitude. More than half of the investigated foxes were hosting ticks. Similar prevalence values were reported from other large-scale studies [18, 22, 26, 36, 37].

Red foxes are important hosts for ticks all over Europe, with at least 17 tick species known to occur on foxes, with regional differences among tick faunas. There are three species of ticks (I. canisuga, I. hexagonus and I. ricinus) which are commonly found on foxes in most studied regions, but their prevalence and abundance may exhibit large variations [26, 36, 37]. In addition to these common species, in most regions there are several other tick species which may be the locally dominant fox ticks. Foxes from the Western Mediterranean region are parasitized primarily by Rhipicephalus species (R. pusillus, R. sanguineus (s.l.) and R. turanicus) and I. ventalloi [19, 22, 36–39]. Further north, in regions with climate determined by the Atlantic Ocean, the tick fauna of foxes includes almost exclusively I. canisuga, I. hexagonus and I. ricinus [21, 40]. In central Europe, Haemaphysalis concinna and D. reticulatus appear complementary to these three [18, 25, 26, 41, 42]. In southern Europe (Italy, Croatia, Turkey) most foxes are hosting (in addition to the three main species and the typical Mediterranean Rhipicephalus spp.) also Haemaphysalis species (H. erinacei, H. inermis, H. parva, H. punctata and H. sulcata) and rarely, D. marginatus [27, 43–45].

The tick fauna of red foxes from Transylvania is similar regarding species composition to most central and western European studies, as the three most commonly found tick species are I. hexagonus, I. canisuga and I. ricinus. However, the fourth species (D. marginatus) was reported only from the southern part of the continent [44]. While in most studies I. ricinus or I. canisuga are the dominant tick species in foxes, in our study I. hexagonus was found to have the highest prevalence and intensity. Similar prevalences of I. hexagonus were reported only by Harris & Thompson [21] for suburban foxes in London and by Dominguez [36] for the mountainous region of Burgos in Spain, however in both cases one of the other two Ixodes species was the dominant tick. Ixodes hexagonus is a burrow-dwelling tick, adapted to parasitize mammals typically using underground burrows (carnivores and hedgehogs, Erinaceus spp.). While Sobrino et al. [19] suggested that the geographical distribution of I. hexagonus is not strictly limited by climate (because of the buffering effect of the microclimate of the host’s burrows) there are major differences among prevalences on the continent. While most studies failed to confirm the presence of I. hexagonus in southern Europe and it was scarcely found in central Europe, it was reported in high numbers from the mountainous areas of Northern Spain [36] and in countries with moist Atlantic climate (UK) or northern Germany [21, 26]. Although all over in Europe foxes use underground burrows for breeding, it seems that this tick species prefers areas with higher atmospheric humidity. The high prevalence of I. hexagonus in central Romania is probably linked to higher atmospheric moisture levels compared to neighboring countries, due to higher elevations (and associated higher levels of rainfall) of fox occurrences than in Croatia, Hungary or Germany.

Ixodes canisuga is another typical burrow-tick, commonly occurring in foxes [21]. The prevalence recorded in our study is similar to the ones found in Italy, UK or Spain, but lower than in Hungary [18] or Germany [26]. The prevalence of I. ricinus on foxes in our study was lower than in those studied in Germany [26] and Hungary [18], but was higher than in most other studies reporting this species from foxes [25, 37, 39]. Most likely, this is determined by the high frequency of forest cover in our study area, as this tick species shows high affinity towards forests [46]. Dermacentor marginatus is a tick with an eastern European distribution, and thus rarely recorded on foxes, with only one published study reporting a prevalence similar to the one recorded in Romania [44].

The red fox is the most common carnivore of Europe, and they are commonly encountered in most habitats and elevations from seashores to alpine regions, with winter harshness being the only known limit for its occurrence [35]. The species is the most common carnivore in Romania, and its distribution covers the territory of the entire country [29]. We found ticks on foxes collected in an altitudinal range from 91 to 1789 m a.s.l. (covering lowlands to high alpine regions in Romania) and the parasite burdens were diverse, seemingly being influenced primarily by altitude. Foxes from lowlands had the highest prevalence of tick parasitism and diversity, but a low intensity, which was the highest in hilly areas. While the higher overall prevalence may be caused by the overall higher number of tick species present at low altitudes, we have no explanation for the lower intensity. There were significant differences in tick species’ composition in red foxes in relation to altitude, land use and habitat composition. One of the tick species encountered (D. marginatus) occurred only at low altitudes (<200 m), while another (I. canisuga) also was limited by altitude, with an upper limit of occurrence at 521 m a.s.l. Although the other two tick species showed a higher tolerance towards altitude, their median occurrences showed that their distributional optima were different. Ixodes hexagonus was found most commonly in hilly areas (75% of all occurrences within the range of 211–509 m a.s.l.), with the highest prevalence and intensity found also in this range. Ixodes ricinus had a similar wide distributional range, however, its highest prevalence was found in mountain areas (Table 4).

Tick distribution showed a regional trend, with different habitats and land use generally linked to different tick faunal compositions. High percentage of forest cover inside the sample cell was negatively correlated with the presence of D. marginatus and I. canisuga, with D. marginatus common in habitats containing high percentage of arable land (Table 5). Although D. marginatus is primarily a tick species of grasslands and open landscapes [47], hence its wide association with the presence of agricultural areas is easily understood, we have no such explanation for I. canisuga. Arable areas also favored the presence of I. hexagonus, this being the only land use category predicting its occurrence. As most tick species were positively correlated with the presence of arable lands, this is the most important predictor for the high incidence of mixed infestations as well, with all the other predictors negatively influencing the occurrence of multiple infestations in foxes. No visible influence of any predictor was established for I. ricinus. This denotes the wide generalist character of this species, being by far the most common tick in Romania [46].

The four tick species found in Transylvania are common parasites of mostly wild and domestic carnivores [48]. Three of these, D. marginatus, I. hexagonus and I. ricinus, are commonly occurring on small mammals and humans [49, 50], while D. marginatus and I. ricinus also occur on ruminants [51]. Their epidemiologic importance is long established, with these species being vectors of certain Anaplasma spp. [52, 53], Babesia spp., Rickettsia spp., zoonotic viruses and - except for D. marginatus - Borrelia spp. [1]. Their geographical distribution range has been also established for a long time, but their ecology and the influence of bio-climatic factors on their distribution and population dynamics still lack details. By elucidating the importance of altitude and habitat structure in shaping the tick fauna of red foxes we provide new tools for establishing the epidemiological importance of this carnivore host. As foxes are frontrunners of the wildlife urbanization process [12], with a continuous increase of their numbers in urban areas [13], the knowledge of their ticks’ ecology (and the pathogens vectored by these) is of utmost importance.

Conclusions

Altitude influenced the intensity of parasitism, with highest intensity observed for all Ixodes species in hilly areas. Dermacentor marginatus occurred only in lowlands, I. canisuga in lowlands and hilly areas while the other two species occurred in all the regions studied. Foxes from lower altitudes had the most tick species associated, with most incidences of co-parasitism noted at low elevations. Land use affected tick species composition, with the presence of D. marginatus strongly associated with the extension of arable areas and lack of forests. The presence of I. hexagonus was determined only by the extent of arable lands.

References

Dantas-Torres F, Chomel BB, Otranto D. Ticks and tick-borne diseases: a One Health perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:437–46.

Day MJ. One health: the importance of companion animal vector-borne diseases. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:49.

Smith FD, Ler W. Prevalence of Babesia and Anaplasma in ticks infesting dogs in Great Britain. Vet Parasitol. 2013;198:18–23.

Farkas R, Estrada-Peña A, Jaenson TG, Pascucci I, Madder M, Salman M, et al. Basic biology and geographical distribution of tick species involved in the transmission of animal pathogens, including zoonoses. In: Salman, MD, editor. Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases: Geographical distribution and control strategies in the Euro-Asia region. Wallingford, UK: CABI; 2012, p. 6-26.

Lucherini M, Lovari S. Habitat richness affects home range size in the red fox Vulpes vulpes. Behav Process. 1996;36:103–5.

Holmala K, Kauhala K. Habitat use of medium-sized carnivores in southeast Finland-key habitats for rabies spread? Ann Zool Fen. 2009;46:233–46.

Pasanen‐Mortensen M, Pyykönen M, Elmhagen B. Where lynx prevail, foxes will fail-limitation of a mesopredator in Eurasia. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2013;22:868–77.

Šálek M, Drahníková L, Tkadlec E. Changes in home range sizes and population densities of carnivore species along the natural to urban habitat gradient. Mammal Rev. 2015;45:1–14.

Sikó-Barabási B, Deplazes P, Ceica C, Tivadar CS, Bogolin I, Popescu S, et al. Echinococcus multilocularis in south-eastern Europe (Romania). Parasitol Res. 2011;108:1093–7.

Nouvellet P, Donnelly CA, De Nardi M, Rhodes CJ, De Benedictis P, Citterio C, et al. Rabies and canine distemper virus epidemics in the red fox population of northern Italy (2006–2010). Plos One. 2013;8(4):e61588.

Nowakiewicz A, Zięba P, Ziółkowska G, Gnat S, Muszyńska M, Tomczuk K, et al. Free-living species of carnivorous mammals in Poland: Red fox, beech marten, and raccoon as a potential reservoir of Salmonella, Yersinia, Listeria spp. and coagulase-positive Staphylococcus. Plos One. 2016;11(5):e0155533.

Devenish-Nelson ES, Harris S, Soulsbury CD, Richards SA, Stephens PA. Demography of a carnivore, the red fox, Vulpes vulpes: what have we learnt from 70 years of published studies? Oikos. 2013;122:705–16.

Plumer L, Davison J, Saarma U. Rapid urbanization of red foxes in Estonia: distribution, behaviour, attacks on domestic animals, and health-risks related to zoonotic diseases. Plos One. 2014;9(12):e115124.

Scott DM, Berg MJ, Tolhurst BA, Chauvenet AL, Smith GC, Neaves K, et al. Changes in the distribution of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in urban areas in Great Britain: findings and limitations of a media-driven nationwide survey. Plos One. 2014;9(6):e99059.

Vuorisalo T, Talvitie K, Kauhala K, Bläuer A, Lahtinen R. Urban red foxes (Vulpes vulpes L.) in Finland: A historical perspective. Landscape Urban Plan. 2014;124:109–17.

Trewhella WJ, Harris S, McAllister FE. Dispersal distance, home-range size and population density in the red fox (Vulpes vulpes): a quantitative analysis. J Appl Ecol. 1988;25:423–434.

Kühn A, Schulze C, Kutzer P, Probst C, Hlinak A, Ochs A, et al. Tularaemia seroprevalence of captured and wild animals in Germany: the fox (Vulpes vulpes) as a biological indicator. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:833–40.

Sréter T, Széll Z, Varga I. Ectoparasite infestations of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Hungary. Vet Parasitol. 2003;115:349–54.

Sobrino R, Millán J, Oleaga Á, Gortázar C, de la Fuente J, Ruiz-Fons F. Ecological preferences of exophilic and endophilic ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) parasitizing wild carnivores in the Iberian Peninsula. Vet Parasitol. 2012;184:248–57.

Najm NA, Meyer-Kayser E, Hoffmann L, Herb I, Fensterer V, Pfister K, et al. A molecular survey of Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. in red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and their ticks from Thuringia, Germany. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2014;5:386–91.

Harris S, Thompson GB. Populations of the ticks Ixodes (Pholeoixodes) hexagonus and Ixodes (Pholeoixodes) canisuga infesting suburban foxes, Vulpes vulpes. J Zool. 1978;186:83–93.

Martínez-Carrasco C, De Ybáñez MR, Sagarminaga JL, Garijo MM, Moreno F, Acosta I, et al. Parasites of the red fox (Vulpes vulpes Linnaeus, 1758) in Murcia, southeast Spain. Rev Med Vet. 2007;158:331–5.

Magi M, Calderini P, Gabrielli S, Dell’Omodarme M, Macchioni F, Prati MC, et al. Vulpes vulpes: a possible wild reservoir for zoonotic filariae. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:249–52.

Lledó L, Giménez-Pardo C, Domínguez-Peñafiel G, Sousa R, Gegúndez MI, Casado N, et al. Molecular detection of hemoprotozoa and Rickettsia species in arthropods collected from wild animals in the Burgos Province, Spain. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:735–8.

Kočišová A, Lazar P, Letková V, Čurlík J, Goldová M. Ectoparasitic species from red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in East Slovakia. Veterinarski Arhiv. 2006;76:59–63.

Meyer-Kayser E, Hoffmann L, Silaghi C, Pfister K, Mahling M, Passos LM. Dynamics of tick infestations in foxes in Thuringia, Germany. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2012;3:232–9.

Jemeršić L, Dežđek D, Brnić D, Prpić J, Janicki Z, Keros T, et al. Detection and genetic characterization of tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) derived from ticks removed from red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and isolated from spleen samples of red deer (Cervus elaphus) in Croatia. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2014;5:7–13.

Mihalca AD, Dumitrache MO, Magdaş C, Gherman CM, Domşa C, Mircean V, et al. Synopsis of the hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) of Romania with update on host associations and geographical distribution. Exp Appl Acarol. 2012;58:183–206.

Adamescu MC, Cazacu C, Ionescu O, Ionescu G, Jurj R, Popa M, et al. Mapping trends of large and medium size carnivores of conservation interest in Romania. Ann Forest Res. 2011;57:97–107.

Dengler J, Janišová M, Török P, Wellstein C. Biodiversity of Palaearctic grasslands: a synthesis. Agr Ecosyst Environ. 2014;182:1–14.

Dorresteijn I, Loos J, Hanspach J, Fischer J. Socioecological drivers facilitating biodiversity conservation in traditional farming landscapes. Ecosystem Health Sustain. 2015;1:1–9.

Mikulcak F, Newig J, Milcu AI, Hartel T, Fischer J. Integrating rural development and biodiversity conservation in Central Romania. Environ Conserv. 2013;40:129–37.

Feider Z. Arachnida. Acaromorpha, Suprafamily Ixodoidea (Ticks), Fauna of the People’s Republic of Romania. Bucharest: Academiei Republicii Populare Române; 1965 (In Romanian).

Nosek J, Sixl W. Central-European ticks (Ixodoidea). Mitt Abteil Zool Botanik Landesmus Joanneum. 1972;1:61–92.

Bartoń KA, Zalewski A. Winter severity limits red fox populations in Eurasia. Global Ecol Biogeogr. 2007;16:281–9.

Dominguez G. North Spain (Burgos) wild mammals ectoparasites. Parasite. 2004;11:267–72.

Millán J, Ruiz-Fons F, Márquez FJ, Viota M, López-Bao JV, Paz Martín-Mateo M. Ectoparasites of the endangered Iberian lynx Lynx pardinus and sympatric wild and domestic carnivores in Spain. Med Vet Entomol. 2007;21:248–54.

Rózsa L, Reiczigel J, Majoros G. Quantifying parasites in samples of hosts. J Parasitol. 2000;86:228–32.

Estrada-Peña A, Oteo JA, Estrada-Pena R, Gortazar C, Osacar JJ, Moreno JA, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi sensulato in ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) from two different foci in Spain. Exp Appl Acarol. 1995;19:173–80.

Ross JG, Fairley JS. Studies of disease in the Red fox (Vulpes vulpes) in northern Ireland. J Zool. 1969;157:375–81.

Lassnig H, Prosl H, Hinterdorfer F. Zur Parasitenfauna des Rotfuchses (Vulpes vulpes) in der Steiermark. Wiener Tierärztl Mschr. 1998;85:116–22.

Hornok S, Fuente J, Horváth G, Fernández de Mera IG, Wijnveld M, Tanczos B, et al. Molecular evidence of Ehrlichia canis and Rickettsia massiliae in ixodid ticks of carnivores from South Hungary. Acta Vet Hung. 1999;61:42–50.

Gabrielli S, Kumlien S, Calderini P, Brozzi A, Iori A, Cancrini G. The first report of Hepatozoon canis identified in Vulpes vulpes and ticks from Italy. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2010;10:855–9.

Lorusso V, Lia RP, Dantas-Torres F, Mallia E, Ravagnan S, Capelli G, et al. Ixodid ticks of road killed wildlife species in southern Italy: new tick-host associations and locality records. Exp Appl Acarol. 2011;55:293–300.

Bursali A, Keskin A, Tekin S. A review of the ticks (Acari: Ixodida) of Turkey: species diversity, hosts and geographical distribution. Exp Appl Acarol. 2012;57:91–104.

Mihalca AD, Gherman CM, Magdaş C, Dumitrache MO, Györke A, Sándor AD, et al. Ixodes ricinus is the dominant questing tick in forest habitats in Romania: the results from a countrywide dragging campaign. Exp Appl Acarol. 2012;58:175–82.

Hornok S, Farkas R. Influence of biotope on the distribution and peak activity of questing ixodid ticks in Hungary. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:41–6.

Otranto D, Cantacessi C, Dantas-Torres F, Brianti E, Pfeffer M, Genchi C, et al. The role of wild canids and felids in spreading parasites to dogs and cats in Europe. Part II: Helminths and arthropods. Vet Parasitol. 2015;213:24–37.

Mihalca AD, Dumitrache MO, Sándor AD, Magdaş C, Oltean M, Györke A, et al. Tick parasites of rodents in Romania: host preferences, community structure and geographical distribution. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:266.

Estrada-Peña A, Jongejan F. Ticks feeding on humans: a review of records on human-biting Ixodoidea with special reference to pathogen transmission. Exp Appl Acarol. 1999;23:685–715.

Hornok S, Horváth G, Jongejan F, Farkas R. Ixodid ticks on ruminants, with on-host initiated moulting (apolysis) of Ixodes, Haemaphysalis and Dermacentor larvae. Vet Parasitol. 2012;187:350–3.

Rymaszewska A, Grenda S. Bacteria of the genus Anaplasma - characteristics of Anaplasma and their vectors: a review. Vet Med. 2008;53:573–84.

Dumitrache MO, D’Amico G, Gherman CM, Matei IA, Ionică AM, Paştiu AI, et al. Prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, in Ixodes ricinus parasitizing on Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Romania. Bul USAMV Cluj Vet Med. 2015;72:134–7.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported from grant PN-II-RU-TE-2014-4-1389. The study was conducted under the frame of the EurNegVec COST Action TD1303. We would like to thank A. Balea, D. T. Ionescu, A. M. Ionică, J. B. Kiss, I. A. Matei and D. I. Mărcuțan for their efforts during different phases of sample collection.

Funding

This research was supported from grant PN-II-RU-TE-2014-4-1389.

Availability of data and material

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The raw data are freely available (upon registration) on the www.geo-parasite.org webpage.

Authors’ contributions

Study design by ADS. Tick collection by CMG, ADS and GDA. MOD identified the ticks; CD built the model and prepared the maps. ADS wrote the manuscript. ADM supervised parasitological work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All samples used in this study were collected from corpses of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes), a common pest/game species in Romania. The corpses were results of organized game-keeping activities, the animals being shot by professional and amateur hunters. No live animal was harmed for this study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sándor, A.D., D’Amico, G., Gherman, C.M. et al. Mesocarnivores and macroparasites: altitude and land use predict the ticks occurring on red foxes (Vulpes vulpes). Parasites Vectors 10, 173 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2113-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2113-9